Toward A New Era of Nation-States, Part VII: The Will to Power & Unbridled Egoism, Part 1

Posted By Algis Avižienis On In North American New RightPart I here [2], Part II here [3], Part III here [4], Part IV here [5], Part V here [6], Part VI here [7]

Part 1 of 2

A life devoted to self-aggrandizement might appear to be in accord with nature, which sanctions the will to power. But in reality, overweening individualism cannot lead to the happy outcome that Aristotle conceived as the ultimate goal of man’s life. Power serving exclusively egotistical ends is relatively short-lived and thus of a lower order of magnitude.

Socially-Conscious Criminals

Over the course of 15 years, Pablo Escobar and Carlos Lehder of Columbia together built up a vast cocaine smuggling enterprise that earned them an estimated 60 billion in assets, measured in today’s USD. Escobar is considered one of modern history’s wealthiest criminals, but the crime empire that he and Lehder created was not destined to survive for long.

In 1987, Colombian National Police apprehended Lehder and extradited him to the US. A few years later, Escobar was hunted down and killed by Colombian law enforcement agents. The wealth that these two men amassed was either confiscated by government authorities or divided up between family members or appropriated by criminal associates. Although the Colombian cocaine business still flourishes, the structures that Escobar and Lehder created have been supplanted by other mechanisms run by new drug lords.

One reason why both drug kingpins survived as long as they did was that, early on in their careers, both men realized that naked self-aggrandizement was not a viable option in their perilous business. Covering the flanks of their in-country operations, Escobar and Lehder worked to build up a measure of popular approval among the poor of Colombia. Escobar spent millions on housing for slum dwellers and, exploiting the good will generated by this largesse, won a seat as a member of the Columbian Congress. The cocaine king even hoped to eventually become President of Columbia. Escobar’s funeral in late 1993, was attended by 25,000 well-wishers and supporters. Carlos Lehder was also politically active. He founded a radical political movement and gave interviews in which he portrayed his drug smuggling operations as part of a broader war against US imperialism.

Robber Baron Philanthropy

By the early part of the 20th century, John D. Rockefeller had succeeded in monopolizing nearly the entire US petroleum sector, thereby becoming the first billionaire in US history. Rockefeller’s high-handed dealings, his ruthless elimination of competing oil refining and marketing companies, his bribery of US legislators and government regulators, made the oil baron one of the most vilified business figures of the time. The muckraking writer Ida Tarbell exposed the more scandalous features of Rockefeller’s climb to the top in her “The History of the Standard Oil Company.” This well-known work of investigative journalism fed popular revulsion against Rockefeller’s overbearing methods, which threatened to involve the US government in serious legal actions against his monopoly power.

Reacting to a growing chorus of public criticism, this overbearing oligarch began remaking his public image by launching philanthropic initiatives. He began pouring increasing amounts of his wealth into support for medicine, education, churches, and missionary work abroad. Rockefeller funded the establishment of the University of Chicago. Some biographers note that this oil magnate spent half his career building up the Rockefeller fortune and the second half giving it away through philanthropy.

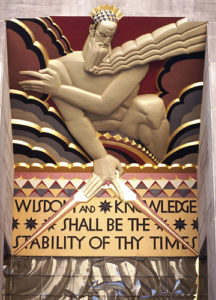

Other ruthless oligarchs showed remarkably similar tendencies. Among his other gestures of largesse, the financier J. P. Morgan donated valuable art works to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1937, Andrew W. Mellon, a financier and long-serving Treasury Secretary, established the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. with a major donation of art treasures, many of which were purchased from the financially hard-pressed Bolshevik regime. In the 1930s, Edmund James de Rothschild gave away 40,000 engravings and drawings to the Louvre Museum in Paris.

We might very well ask why people driven by a ferocious thirst for personal wealth wind up sharing so much of it through philanthropy. Since we have previously identified the will to power as the overriding instinct of life, we must recognize that the obsession with making money is only a specific subset of the dominant drive. The instinct to acquire ever more power inevitably draws the protagonist into a broader sphere of interaction with people that goes well beyond the world of pure money-making.

The Social Nature of High-Grade Power

It is in the field of interpersonal relations that the aspiring millionaire will encounter the greatest opportunities, and the greatest threats. Thus, anyone hoping to amass a great deal of wealth will learn the importance of the art of managing people. A fabulously rich person must possess, or at least pick up, some management skills, if only to prevent his advisors and associates from taking advantage of him. At the highest summits of economic or political power, the prominent personalities must know how to cultivate among their followers a sense of trust, credibility, confidence, or at a minimum, a commonality of interests.

The process of accumulating money, or any power for that matter, follows the pattern of an upward spiral. Wealth is not only a highly-desired end; it also represents a means for acquiring more power. Therefore, the more assets one collects over time, the more tools will be available for further advances. Countless self-improvement guides make the same point: the hardest part of getting rich is earning the first million USD. Similarly, those who undertake careers in corporate or government bureaucracies will discover that the first few years of service are the hardest. This is a proving period in which the beginner must demonstrate his competence and establish personal contacts which will open many doors in the coming years.

In sum, the person who follows his innermost instinct and accumulates power in a robust and focused manner will find himself deeply involved in developing contacts with other people and groups of people. A businessman, politician or bureaucrat will be obliged to strenuously cultivate relationships with those who might be useful in their careers. The topflight government or corporate operators must resign themselves to work schedules crowded with telephone calls, staff meetings, appointments, receptions, and seminars. Their typical workweek exceeds 62 hours by some estimates.

Success in harnessing the power of other individuals, however, is not a one-way street. A leader must not only win over adherents or clients by offering them convincing advantages, he is also compelled to keep his subordinates satisfied by guaranteeing them a steady flow of rewards. In short, the price for obtaining high-grade power is slavish dedication to the interests of others 24 hours per day.

The Highest-Quality Power is Long-Lasting

The great effort demanded in expanding the sphere of personal interactions inescapably carries with it the cost of time expended for this end. Here we can observe in a general sense how the concepts of mass (or quantity) and time revolve around each other, drawing the power seeker into an upward turning spiral.

In order to gain power, the subject must invest a very significant quantity of his life energy in fortifying selected associations of people. This is how the process of fusing individual identity into associations begins. Through continuing interactions with a group, the individual becomes a part of a greater whole. As the individual transfers more of his life substance to the association, he also transposes his will to power to the members of a group. Hence the association is impelled to grow stronger just as the separate individual must continually build up his strength by pursuing profit, gain or advantage.

The really significant associations and institutions can accomplish more than one person precisely because they are comprised of numerous individuals. An organization can do more than just one person, but its extended membership also represents a heightened level of durability with respect to the encroachments of time. It can lose one or two members through resignation or death, but the rest of the association will be there to continue the corporate life of the group. The collective will to power it derives from its constituent parts will impel it to grow.

The University of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art and the Rothschild art endowment at the Louvre Museum have all survived John D. Rockefeller, Andrew W. Mellon, and Edmund James de Rothschild. Irrespective of the social damage these personalities caused in their lifetimes, their cultural contributions nevertheless remain and soften the contours of their public images.

Anyone who has contemplated the nature of power will recognize that a short burst of energy typically does not reflect power of a high order. More often, power is inextricably linked to durability — the capacity to oppose the environment projected far into the dimension of time.

Time exists in the interactions of matter and energy, which we may designate as events. As a dimension of existence, time is a measure of the quantity of events — the revolutions of the earth around its axis, the seasonal migrations of birds, the late summer harvests of wheat, or US Presidential elections, for example. An extended period contains within itself a greater mass of manifested power than a brief interlude. Consequently crass individualism is blind to an essential element of power — the capacity to endure. The personal achievements of those who consistently violate generally accepted rules of play will likely not survive much beyond their lifetimes. As such, excessive individualism ultimately leads the self on a descending path to weakness.

Individualism: A Persistent By-Product of Civilization.

Yet civilization itself and its attendant process of urbanization seem to foster an individualistic outlook. It could very well be that the individual’s habit of self-sacrifice for others, which underpins social cohesion in any society, rests on a kind of moral capital that man accumulated when he lived in self-sufficient agricultural communities.

According to Fernand Braudel, the noted French historian, for centuries the vast majority of Europeans spent practically their entire lives in essentially unchanging farming communities. Until the end of the 18th century, few rural inhabitants travelled more than 50 km from their birthplace during their entire lives. From the time of the Roman Empire to the French Revolution, the proportion of rural to urban inhabitants remained at a steady 90 percent.

Before the Industrial Revolution and the great exodus from farming villages to the expanding factory towns, a typical European had been accustomed to live surrounded by his large family and neighbouring kin. European rural folk could count on their family and neighbours for help in performing farm work and providing psychological support. Core family solidarity and mutual assistance traditions flowed more or less without interruption from one generation to the next.

Children inherited their parents’ land, work skills, outlook on life, aesthetic preferences, and moral precepts. At a very early age they also learned the reciprocal nature of giving and taking in a long-term context. In return for their upkeep, they were expected to perform the lighter farm work for their families. There simply was little room for an individualistic approach to life. The common struggle to survive in a harsh environment focused attention on the commonality of interests of the family, which was a more or less a self-sufficient economic unit.

As Europeans increasingly became urbanized in the 19th century, however, they began drawing on this social capital, which gradually gave way to a self-centered way of life and to the alienating atmosphere of the city. As working conditions in the new cities improved and as mass literacy spread, Europeans could devote more time to study and self-improvement.

The fundamental relationship between children and their parents was altered, since urban families no longer required the work of their children as essential contributions to their economic welfare. As the residents of the growing towns and cities emerged from poverty, they assumed a more permissive attitude towards the younger generation. Parents gave their offspring what they could without requiring compensation in the form of grinding farm chores. Children were encouraged to learn a trade or study hard and improve their minds.

The phenomenon of children who grow up to become self-assertive individuals is associated with industrialization and an urban model of life, which now predominates in most of Europe and North America. Fewer than 10 percent of the populations of modern European or North American countries live in rural communities – a proportion which represents a complete reversal of millennia of human experience. No doubt the transition away from agricultural labor to industrial work fortified the ideas of individual liberty that gained traction in the early 19th century.

Initially, life in the new industrial settlements was marked by fragmentation, anonymity, and indifference. Unprecedented urban growth as well as alternating periods of economic expansion and depression exploded earlier expectations of continuity. For these reasons, social and political stability in the growing European cities came under increasing stress. Crime, overcrowding, epidemics, prostitution, and gross exploitation of factory workers were just a few of the social ills afflicting entire industrialized regions and countries. Outbreaks of revolutionary violence in Western Europe followed in regular succession, including the bloody uprisings of 1830, 1848, and 1870.

Family solidarity and mutual assistance traditions brought over from the farm helped shield newly-urbanized Europeans from the worst abuses of concentrated economic power. The Christian clergy also contributed to the re-establishment of a measure of intimacy and a community spirit by founding urban parishes for the benefit of the uprooted peasants. But it was becoming apparent that new political ideas would be required to re-establish social cohesion.

The Rise of Individualism and the Fall of Birth Rates

Demographic experts note a correlation between the level of urbanization and labour mobility, on the one hand, and the stability of social groups and families on the other. The shift from agricultural to urban communities is associated with rising divorce and falling birth rates. Abandoning traditions of farm communities, the individual becomes accustomed to living for himself. A city dweller does not require a multitude of children and relatives to help with the farm work. This is one reason why the societies which have achieved the highest levels of urbanization and mobility are those which are growing older at the fastest rates.

A person establishing a family cares about the transmission of his vitality to another generation. He believes that his life has meaning. Young parents must invest a significant part of their creative energies in supporting and raising children. For many this will provide the best opportunity they will ever have of influencing their society in a meaningful way. A person who does not have faith in the durability of his legacy will be oriented more to himself and sensual gratification.

The symbol of 20th century industrial civilization could very well be the automobile, the embodiment of fervent aspirations of many and a pillar of the mobile society. The automobile provides instant gratification of the power urge, easily overcoming time and space limitations. That is why some observers have remarked that modern man is more inclined to maintain two autos in his garage than raise two children at home. Modern consumerism narrows the concept of human power to the momentary sensual realm of the individual. One enjoys the pleasures of the here and now for oneself. The consumer seeks personal enjoyment and comfort; the acquisition and demonstration of wealth fortifies the individual‘s social position.

But by abandoning hopes of establishing a family, playing a constructive role in the community, or participating in the political process, the individual disarms in the face of more resolute forces. As he liberates himself from social ties and obligations, the individual does indeed attain some personal freedom, but he also forfeits true power, if we interpret power as the capability of exercising lasting influence on one’s human environment.

Nationalism Restores Social Solidarity for a Time

It was no accident that liberal democracy, socialism, and nationalism emerged as the dominant political ideas of the 19th and 20th centuries. Each in its own way attempted to revive the sense of community, which had been lost in the dark tenements and back alleys of factory towns. Social democracy sought to cushion the impact of ballooning disparities in income and welfare, which triggered resentment and undermined solidarity. Liberal democracy offered constitutions, parliaments, expanded suffrage, and a free press to give the individual, at least formally, the means by which he might shape public life in mass societies.

At the time nationalism emerged as the most potent unifying force in part because it reflected already existing sentiments of affinity based on common languages, culture, and long historical interaction. But it also managed to articulate a much wider sphere of European aspirations than the other newly emerging currents of thought. Nationalist convictions, allied with liberal democratic ideas, successfully attacked aristocratic rule and undermined multi-national empires.

Nationalism satisfied the individual’s need for continuity and purpose in a time of uncertainty. It posited the idea of a people as an organic whole encompassing past, present, and future generations – all working towards shared goals. Nationalists exhorted the members of a national community to take pride in their past achievements and seek new accomplishments for the benefit of posterity. For many Europeans these ideas rekindled hopes of finding meaning in their uprooted lives.

Unfortunately, subsequent historical events eliminated the national idea as a potent, binding force in Europe. At the conclusion of World War II, two universal doctrines, US free market liberalism and Soviet Communism, were grafted onto the body of European political thought. The universal doctrines, which the superpower conquerors transplanted on the ruins left behind by the war, did not produce durable communities. Instead, they helped to bring forth a mass of atomized individuals pursuing individual ends. Social fragmentation, caused by industrialization and effectively counteracted by nationalism for over a century, resumed its course. Individualism is now firmly planted into the European psyche.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: