The Charge of the Light Brigade

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledWhen I was in college, the campus offered a film series called Twice-Told Tales. You would view a film followed by its remake three days later. Films like Dangerous Female (1931), starring the well-known actor Ricardo Cortez. Whatever happened to Ricardo Cortez? For that matter, Dangerous Female? The remake did rather better: The Maltese Falcon (1942), starring Humphrey Bogart. We sure know him.

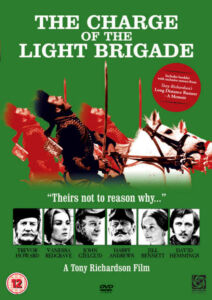

The Charge of the Light Brigade was another, with 1936 action swashbuckler Errol Flynn, and it’s a great film, but I was intrigued two nights later by The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), directed by Tony Richardson with an all-star 1960s British cast, headed by David Hemmings. There’s swashbuckling, but also a thoughtful panorama of Victorian Britain engaged in one of history’s less useful wars.

The film opens with, and is interspaced with, animation pieces by Richard Williams. It begins with a cartoon of France and Austria, then comes Turkey, a gobbler in a fez poking around. Out of the horizon rises the evil Russian bear, scattering feathers as it prepares to devour Turkey. France and Austria haplessly look west as the British lion takes shape, wakes, sees this outrage, roars, then puts on a bobby’s helmet — the world policeman.

The animation depicts patriotic and prideful bits of British resolve, industry, and the science of the period, with mottos like Britannia Encourages the Industry of the Globe. Animation sequences recur in the movie much like Brechtian stage effects, showing the official history while we delve into the human aspects. The action dissolves to normal cinema as the 11th Hussars prepare for inspection, the band playing, sabers glistening, reviewed by a human saber, its regimental commander Lord Cardigan (Trevor Howard). In red hair and long mustaches, he looks like Yosemite Sam in a busby. Cardigan smugly inspects his men as an interior monologue reveals his thought processes, such as they are:

I do not pretend to recount my life in any detail what is what.

No damn business of anyone what is what. I am Lord Cardigan.

That is what.

He’s proud of the 11th Hussars, who, because of their tight red trousers, are called the “cherry bums.” Cardigan is earthy but stern: “If they can’t fornicate, they can’t fight, and if they don’t fight hard, I’ll flog their backs raw for all their fine looks.”

Into this right little regiment rides Captain Nolan (David Hemmings), appropriately dressed in black, for he is a symbol of doom to Cardigan — and, when his philosophy comes out, death itself. Assigned to the 11th, he will become Cardigan’s archenemy, but for now plays the spy to see how the regiment comports itself. He is hallooed by William (Mark Burns), an old friend, and meets William’s fiancé Clarissa (Vanessa Redgrave). The trio becomes inseparable, and Clarissa’s shy but brilliant, comely eyes immediately see possibilities in Nolan.

The film goes through a rapid series of scenes: William and Clarissa’s wedding and its sunlit view of upper-class Britain’s gaiety, then London’s almost subterranean slums as the 11th’s recruiting party looks for new troopers, led by their Sergeant Major (Norman Rossington), who is all smiles and earthiness, plugging the life of a Hussar, recounting its glory, most recently fighting at Waterloo. “Waterloo, ah!” the Sergeant Major exclaims.

The recruits are simple. One man says “I’m of bad character. I’m just out of jail.” The Sergeant Major beams. “In that case, you’ve already served Her Majesty.”

The next morning the recruits are in the barracks. A sniffy officer looks them over and offers upper-class encouragement. “The glitter of a Hussar is something I’ve seen the gay ladies pearling their eyes after.”

One recruit assures the officer he’ll do well, only to get a cold look from the officer, then the Sergeant Major shoves him up against the wall, reminding him to never speak to a “hofficer” unless spoken to. Another officer speaks to the Sergeant Major about the recruits, and the Sergeant major is frank: “English recruits are always weak-boned and wobbly.” The officer smugly smiles back. “You notice that officers are never wobbly.”

Nolan, bored with the officer’s mess, looks down on their arrogance and laziness. He’s got a mark against him having served in India, which they consider beneath a proper officer’s bearing. He’s also seen combat and they haven’t, but they scorn Indian service, as they do the “nigger and black rogue” that is Nolan’s Indian servant.

Nolan calls for a new kind of army, ready to modernize and open itself to more efficient tactics. As Nolan explains to a fascinated Clarissa, a soldier must know what is right, and a cavalry officer must have the “strike in his eye.” Nolan mesmerizes her, as he does with William when he calls for reforms that will make a new army that “will bring the first of the modern wars and the last of the gallop.”

But in London, life goes on. A beautiful ball has a ravishing Clarissa and Nolan dance, and we meet a flaming red-headed Fanny Duberly. Her husband is the paymaster for the regiment, a good-natured ass who is in the know, and Fanny almost always begins her conversations with “Duberly says. . .”

There are small, nice touches. Cardigan enters, and it is assumed ladies are lining up to be wooed by him, including a star-struck Fanny. As a dance begins, we see a middle-aged lady step in front of Cardigan, silently trying to get him to ask her to dance. He sees this and sidles off. A friend of his approaches her. One look at the fat friend and the lady stalks off. Cardigan’s friend leers at her and speaks to Cardigan. “They tell me her pitcher has been too often to the well.” Cardigan shrugs. “All this swish and tit gets me nose up.”

Cardigan despises Nolan. At the officer’s mess, only champagne is served, and Nolan, having invited a journalist who orders Moselle, is blamed when the wine bottle is left on the table and Cardigan claims it is beer. Nolan protests it is not, but Cardigan says it is a black bottle, and that means beer. Nolan angrily walks out as Cardigan shouts at him to return. Soon, London is all agog over the “black bottle.” When Cardigan goes to a performance of Macbeth, the commons and middle class in the upper aisles and auditorium taunt Cardigan with catcalls of “black bottle.” He merely rises, smiles, and sits down. He’s totally unflappable, almost reminding me of Trump’s outrageousness to so many. If only Cardigan had Twitter.

The above is what I enjoy most about this film. The dialogue feels very authentic, and London life is more rowdy and open than we’ve been led to believe. The people sass back. Neither Cardigan nor Nolan ever backs down from their beliefs. It can be a stuffy and arrogant society, but it is an honest one. I also admire the costuming. This is one of the few historical films I’ve seen where everyone really looks like the period.

Nolan, while overturning the cart in the regiment, draws closer to Clarissa, and she loves him. They meet clandestinely, and Vanessa Redgrave is the queen of using few words and her eyes to express the passion in Clarissa waiting to break out. She is a decent, upper-class woman, but you sense the fire in her. In a scene where her brother joins the regiment and becomes the butt of a joke by an officer, Nolan enters and one-ups the officer. Clarissa, behind the offending officer, snarls and makes a fist. With a few lines and gestures, Vanessa makes Clarissa a complete character.

Meanwhile, fires are burning at army headquarters. Lord Raglan (John Gielgud), commander of the army, is upset at the black bottle scandal, putting the army’s name in the newspapers. Very bad form. He lost an arm at Waterloo, and like all the British army, lives under the shadow of the Duke of Wellington — literally. An enormous statue of Wellington is outside his window, the Iron Duke almost peeking in. No one knows where to put it. It annoys Raglan because it blocks the sun. Wellington wore black dress in combat, so all senior officer’s uniforms are black like militant bankers or undertakers. He refuses Nolan’s demand for a court-martial, aware war is on the horizon.

Cardigan has his own war, and demands the Sergeant Major spy on Nolan. The Sergeant Major is stunned, and refuses. He cannot play the spy, for he is an honorable man, having laid off drinking since he made corporal.

Cardigan glowers, and offers that Yosemite Sam red-haired temper, but instead of saying “Say yer prayers rabbit,” he coldly addresses his victim: “Sergeant Major, it is better that you take a ball and put it in your brain. You are finished now as if you had never been made.”

Cardigan walks on, and the Sergeant Major sinks on a bench, eyes glazed. At the next inspection, he drunkenly collapses, is flogged for being drunk, and then is dismissed from the regiment. As another sergeant says, “a man needs to be humbled.”

Nolan is angry at the flogging, arguing that punishment needs to be ended. Another officer almost laughs. You have to flog soldiers. Why else will they fight? As the officer smirks, “will you have them fight for money or ideas? That would be un-Christian.”

Nolan’s contempt for these marzipan soldiers is open. The scene moves back to William and Clarissa, and as William happily breaks in a horse for a neighbor, a stunned Clarissa tells Nolan she is with child, and prays it is his. Nolan says nothing and immediately leaves her to join William.

[2]

[2]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [3]

We go to army headquarters where officers cluster over what assignments they’ll get in the war. Into this buzz, Lord Lucan (Harry Andrews) ominously ascends the stairs wearing a tall stovepipe; an evil Abe Lincoln. He expects to command the army. No. Raglan will command, and Lucan simmers. His angry eyes stare as he reluctantly nods acceptance to command the cavalry. Raglan, like a hostess assigning seats at a banquet, announces the unit commanders, mentioning the Light brigade will serve under Cardigan.

Lucan almost explodes. “Cardigan!?” Despite Cardigan being his “empty-headed muff of a brother-in-law,” or perhaps because of it, Lucan despises the man. Raglan sees that a major part of his mission as commander-in-chief will be keeping Lucan and Cardigan from killing each other; if they can actually be turned on the Russians, all for the better.

Throughout all this, Nolan, now assigned to the staff, silently observes the bickering, his eyes in cold judgment.

As Team Captain, Raglan gives a rah-rah speech to his commanders, to defend poor Turkey. “The sick man of Europe,” chimes in Airey, his aide-de-camp. “Yes,” Raglan says, “though I prefer to consider her as a young lady, hands up, fluttering, defenseless. If she should be threatened by the tyrant.” He goes on. “If the Turks go down like cards, flip-flop, then next will be our own solvent.” He means the English Channel. “The Russian will rip our country into shame. The Queen, her Majesty, is sure to be threatened.”

It sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Poor little Turkey. Poor little Serbia. Poor little Belgium. Poor little Poland. Poor little Vietnam. Poor little Kuwait. Poor little Afghanistan — do I see a pattern?

The animation is bombastic: Right Against Might. Ripe and Ready for the Fray.

Aboard their ship departing for Crimea, Nolan confesses to William his itch for war and adventure. William offers him a letter from Clarissa. When he goes to check his mount, Nolan immediately shreds the letter and throws the pieces overboard.

After a confused, uncontested landing, the army marches onto Sevastopol, in full order, band playing, the “dash and fire” Raglan promised Cardigan. In the next scene, soldiers collapse, tumble off their mounts, and men double over as cholera sweeps the ranks.

The battle of the Alma is well-depicted, and when British forces swarm up the hill into the Russian ranks, Airey urges the cavalry be sent in. Raglan smiles and shakes his head. They’re too precious to be used in battle, and anyway, Lucan and Cardigan’s brigades will serve with the artillery between them. That will keep them apart, and so out of trouble. Raglan is quite proud of this strategy, as though he were a Lewis Carroll figure in Wonderland, offering insatiable logic.

Britain celebrates the fall of Sevastopol, but the animated victory festival is premature. Sevastopol is very much untaken, and Russian artillery punches the allied forces in their trenches. Nolan is bitter, and confesses to David. “I had such hopes for this war.” This should get a laugh, and among other characters it would, but Nolan is serious. He is almost tragic, seeing a future war of destruction and wanting to be part of it, even instigating it. As I said, these people are honest in their arrogance, or in Nolan’s case, war-making. This is realistic. Anti-war sentiment didn’t really take off until after World War One.

Nolan reminds me of Hamlet. A prince whose throne — that of battle — has been usurped by a flock of “professional” soldiers resembling Polonius and Claudius. William is Nolan’s Horatio, Clarissa his Ophelia. He offers a brief but stern soliloquy after the battle of the Alma. “I won’t be patient until the noble amateurs are so sick of soldiering and go home,” he says to William. When William says war must be civilized, Nolan is hard. “War is destruction, William. Not fashion. It is standing booted over dead soldiers and their wives. The solution to war is that it is best fought. And when fought, it is best fought to the death.”

For the first time in the film, William looks shocked, seeing a side of Nolan he has never seen before as Nolan calls for savagery. Standing booted over dead soldiers and their wives almost sums up how he has cheated on his friend by taking Clarissa. There is a quiet ruthlessness in Nolan’s character. It’s apparent the war Nolan is made for is the one coming nine years later in America.

When a Russian attack cuts off the British forces from their base and Russian troops spirit off artillery, Nolan is furious and demands Raglan do something. An annoyed Raglan orders an attack of combined cavalry and infantry. Nolan rides off to inform the infantry commander, who refuses to march until he’s had breakfast. Raglan sighs when Nolan gallops to deliver the message. He doesn’t like Nolan, and says so to Airey: “It will be a sad day when England has officers who know too well what they’re doing. It smacks of murder.”

It is the remark of a gentleman soldier, recalling Lee at Fredricksburg, seeing the Union forces mowed down in frontal attack after attack on the Confederate positions. He sadly said: “It is well that war is so terrible, lest we grow too fond of it.”

Lee and Raglan are of the same school. Nolan would make an excellent commander under Grant or Sherman in what would become total war.

Nolan gallops to Cardigan and Lucan to relay the attack. They see no infantry supporting them, and no Russians. There are two valleys. One is where the attack has occurred, the other is an entrenched Russian position with artillery. A direct attack on the latter would be suicide. The problem is that from their vantage point, Cardigan and Lucan can’t see what Raglan and Nolan have seen. Nolan shows them Raglan’s orders and insists they charge. Cardigan and Lucan, for once confused and not blustering or raging, attack.

Nolan rides to William’s side and will fight alongside his friend because it is good. It is war. It is the gallop.

This is the best explanation for what happened to the Light Brigade. In the 1936 movie, acknowledged as fiction even in its opening credits, Flynn was an officer who discovers Surat Khan, a man responsible for the massacre of British troops and families in India, is with the Russians. Flynn amends the orders to get revenge on Surat Khan. Fiction, yes, but it makes dramatic sense. Richardson’s film is realistic, and shows, as Tennyson wrote “that someone had blundered.” The blunder is when the cavalry charges down the wrong valley. The Russians look up, more startled than afraid, one even shaking his head in sorrow. The historical record is the Russians thought the English must have been drunk to make such a direct assault.

Nolan immediately sees the error, and gallops to Cardigan. “Wheel right!”

He screams, and points into the right valley, but a Russian cannon fires, killing Nolan. Nolan was a real officer, and in fact, was the first soldier killed in the barrage.

The cavalry rides past his body, and are torn to pieces by the Russian artillery. To Cardigan’s credit, he led his men from the front, as all British officers were expected to do, and it was remarked he wasn’t aware of the slaughter because he was at the head of the column and could only see ahead.

British officers could be stupid, arrogant, narrow-minded, and chauvinistic, but they were never cowards. To have “shown the white feather” was unthinkable. Victorian bravery is a welcome contrast to World War One, where generals were miles behind at headquarters ordering divisions into machine-gun fire and artillery. . . again and again.

William bravely charges, swift and sure, then swings his saber among the enemy. The Light brigade did achieve their objective, overrunning the artillery — until the Russian cavalry counterattack beat them off.

The action goes to Fanny and Duberly, perched with the rear forces and taking refreshments, unable to see much through the smoke of battle. From the dust and smoke, single figures stumble out like zombies. “Are those the skirmishers?” Fanny asks. An officer replies. “That is the Light Brigade.” She looks through the binoculars, seeing the bloody, torn, shocked men on their mounts or on foot. Her eyes are frozen in shock, like those of Duberly. They’re completely stunned, and there will be no more gossip or tittering. Nor dash and fire. In the phrase of the time, they have seen the elephant.

William rides slowly through the dead and smoke. He’s alive, but his cap is slashed, his face a bloody mask as his eyes offer a thousand-yard stare of someone else who has seen the elephant. He will be the one who must tell Clarissa that Nolan is dead, as well as her brother, who was savagely gored in the assault.

Again, I like how this film gets great performances from minor characters. I feel they are real people, not just a period piece. There is a lot of humor in the beginning, but in the end, they are traumatized at seeing true war replace the “gallop.”

It was said this film was too much a part of the Vietnam and Cold War era to remain popular, but it is one of my favorite movies. It is relevant as ever, especially as we beat the war drum against Russia, China, the Taliban, the Capitol Insurrectionists — take your pick.

The last image of the film is a dead horse, and it slowly freezes into animation, uniting the real and animated world of the film into one.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: