Something in the Water: Epidemics & Enemies in Nineteenth-Century Europe

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled8,057 words

Prologue: The Styx

The half-light of an autumn evening reflected off the Old River and into the face of the boatman. Over and under each subtle ripple and eddy, his eyes darted here to there so quickly that his gaze seemed fixed. As if he took in the whole broad sweep of the Thames with a hungry look-out. Next to him, and charged with steering the dinghy, stooped a young girl, his daughter. She “watched his face as earnestly as he watched the river. But in the intensity of her look, there was a touch of . . . horror.” These were neither fishermen nor cargo carriers, for they were “allied to the bottom of the river rather than the surface” and doing something “they often did and were seeking what they often sought.” It was a subterranean existence of the twilight hours, between day and night, life and death, summertide and midwinter, waterway and shoreline. And as members of this half-world underclass, few noticed them going about their business. They noticed everything.

Suddenly, there!

A slant of “light from the setting sun” touched upon a “rotten stain” which bore “some resemblance to the outline of a muffled human form,” and colored as though with “diluted blood.” The upper half of the boatman disappeared, plunging into the slime, and then reemerged sodden and triumphant and clutching the prize he’d seized. “It was money. He clinked it once, then blew upon it.” The girl recoiled. Of course, he noticed this too.

“It’s my belief that you hate the sight of the very river,” he said reproachfully.

“I — I do not like it, father.”

“As if it wasn’t your living! As if it wasn’t meat and drink to you . . . How can you be so thankless to your best friend, Lizzie?” the boatman admonished, then he tucked the spit-shined silver into his pocket. She resumed her rowing. [1] [2]

So began Charles Dickens’ last completed novel Our Mutual Friend (1864-65) — with a pair of “toshers,” a father-daughter team of scavengers who waded into the fouled waters of the River Thames looking for corpses (and other refuse) and the coin they might find from dead souls to take from them the boatman’s toll. Like the Thames of Dickens’ London, rivers are life-givers — they are, as the grizzled sculler put it, “meat and drink” to entire communities and ransoms for whole civilizations. But when her father pulled the latest body from the water’s depths and strung it alongside their raft, Lizzie knew that the Thames was just as often a river of death — a god-thing that exacted from its followers its own obscene ransom. Feeling ill and unable to share in her father’s enthusiasm, she drew her hood over her face and hid from the cold breath of the river.

[3]

[3]“Bird of Prey,” an original illustration for the serialized version of Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend (1864)

1. A Black Sun from the East

I challenge readers to pick up the next Victorian text they can find and begin reading the first dozen pages. You found at least one mention of disease, did you not? A rattling cough; a dumb artist who fell in love with a prostitute dying of consumption (you know, because “slumming it” was cool); a foolish cousin who went to the tropics and promptly caught yellow fever. If not, then you’ve found the rare diamond of exception that proved the nasty rule: nineteenth-century life and literature were lousy with disease.

As the excerpt above shows, Charles Dickens and other nineteenth-century authors like Mary Shelley were steeped in the stories of antiquity and wrote always with a pupil’s desire to please and pass muster with the great men of the past, as if Virgil, Socrates, or Herodotus were reading over their shoulders. One thing all of these authors, ancient and modern, shared was the brutal reality of poisonous disease, against which there existed precious few panaceas. And Shelley’s dystopian novel The Last Man drew from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War and his famous account of the 430 BC plague that devastated Attica. “The plague,” Shelley’s narrator described, “had come to Athens.” The free, “the noble people of the divinest town in Greece, fell like ripe corn before the merciless sickle of the adversary. Its pleasant places were deserted; its temples and palaces were converted into tombs; its energies, bent before towards the highest objects of human ambition, were now forced to converge to one point, the guarding against the innumerous arrows of the plague.” There was no doubt that it had been preceded and caused by the contagion from the East, “from whence came also a strange story.” On the twenty-first of June, so the rumor went, and an hour before noon,

a black sun arose . . . and eclipsed the bright parent of day. Night fell upon every country, night, sudden, rayless, entire. The stars came out, shedding their ineffectual glimmerings on the light-widowed earth . . . The shadows of things assumed strange and ghastly shapes . . . Such was the tale sent us from Asia, from the eastern extremity of Europe, and from Africa as far west as the Golden Coast. [2] [4]

Last Man used all the tropes of Biblical and Classical stories of Plague Time.

Scholars and epidemiologists are still divided on what caused the Great Athenian Plague of 430 BC — some have assumed that it must have been some variant of the bubonic plague, while others have insisted that it was typhoid, or some hemorrhagic blood-fever, like ebola. Whatever it was, Thucydides claimed that it originated in the Near East and “thence descended into Egypt and Libya and into most of the King’s country . . . [where] it first attacked the population in Piraeus — which was the occasion of their saying that the Peloponnesians [Spartans and their allies] had poisoned the reservoirs.” But the “Peloponnesians” seemed as shocked as anyone else, for as soon as they saw the night-blooms of Athens’ funeral pyres, they wisely withdrew. Thucydides himself caught the disease that eventually killed 100,000 of his countrymen, so his descriptions of the suffering Greeks were among the rawest passages of his History. Healthy people were suddenly struck down with convulsions and an internal heat that caused victims to refuse “to have on [them] clothing or linen even of the very lightest description.” A red rash and leaking pustules covered the body and resulted in unquenchable thirst. Even though many corpses lay out in the streets, “all the birds and beasts that prey upon human bodies, either abstained from touching them, or died after tasting them.” Paroxysms of religious devotion at the gods’ temples rose to a desperate frenzy, then ceased. “Lawless extravagance” spread as quickly as the plague itself, and “Men now coolly ventured [in public] on what they had formerly done in a corner.” [3] [5]

Since Thucydides’ death (by unknown misadventure), the worst plagues always seemed to come out of Az-ee-uh, “the East,” a phrase that was shorthand for “disease,” “decadence,” and shadowy danger. Europeans, lured there by economic prospects in spices and silks, unfortunately traded in another exchange. The Black Death either originated in the central Asian steppes of Tartary, or further east nearer to Tibet and China. Traders then transmitted infected fleas and rats into European ports via shipping vessels. Various swine and bird flus (the Spanish Flu was a misnomer — it likely originated in the Far East) from China and carried along the Silk Road, swept entire continents. I’ve made the point before, but it bears repeating: the rewards of mobility come at a terrible price. And those who reap the best profits never seem to be the ones who reap the worst of the whirlwind.

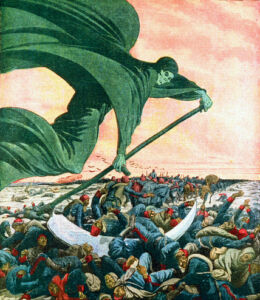

Ironically, the first “modern” historian (Thucydides) who kept the will of the gods and moral hand-wringing out of his narrative, was also the man who inspired the time-honored ritual of the framing of epidemics as morality plays. In these plots, the Plague began as a treacherous eastern enemy slouching toward Babylon. Avaricious merchants and degenerates made their cities the targets of wrath by allowing the enemy succor in European homelands. Incompetent and/or evil elites neglected their duty to halt the spread — or, sometimes even worse: decided to do their duty and halt the spread. Stubborn locals resisted any proposed changes to their customs; anarchy, the ripping of the social fabric, ensued. Strange stories from abroad swirled about as if carried on the wind by mischievous scare-sprites. The interruption of normal life, the loss of memory in many cases, and the overwhelming, all-consuming figure of PLAGUE transported its sufferers and its witnesses to another dimension. Was there anything before the sickness? Would there be anything after the sickness? All dwelled in Plague Country and lived in Plague Time. In the end, the final lines of these dramas always read, “alas for human folly!” and “The King of Plagues will come again!”

[6]

[6]Edwaert Collier, Vanitas Still Life with Jewelry Box (1688); the vanitas painting genre was a popular visual allegory during the early modern period (ca. 1450-1750) that sought to portray the reality that even among the great objects of man’s vanity (learned philosophical tracts and literature, astrolabes and maps, jewelry and an emperor’s crown) was the ever-present specter of death.

In this essay that king of plagues was cholera — the most feared word in the Victorian age. [4] [7] The Black Death and Influenza have overshadowed this disease in our historical memory, and we have collectively forgotten how traumatizing cholera was. It appeared again and again throughout the 1800s, wreaking havoc across the West, from Russia to Italy, and from France to North and South America. All epidemics have had in common (and I mean “epidemic” as a social phenomenon, not simply a medical one) a dizzying array of competing interests and players, some of whom were cynical and some of whom were sincere. Cholera’s story was no different. It was a story of princes and paupers; of town and country; tragedy and farce; of the clash with both the colored peril beyond the West and the sorry urban peril within the West. Most of all, it was about water — the primary necessity for life had suddenly become the cup of death.

NB: Not until the 1860s did researchers agree that contaminated water caused cholera. Before then schemes for prevention and treatment were little more than hands groping about in the dark. I divide the expert medical field of the early Victorian age into two competing camps: the “contagionists” and the “anti-contagionists.” The former argued that diseases like cholera spread through person-to-person contact (although few could agree on exactly why or how this occurred); the latter attributed epidemics to foul air, or miasmas, as well as to a general feeling of malaise. Indeed, for some time many doctors assumed that “fear itself” was a crucial factor in cholera’s deadliness, the spirit of anxiety drawing it like a shark drawn to blood.

2. Cesspits and the City

Few writers captured in such vivid terms the shabby destitution of the nineteenth-century city like Dickens did, and in many of his novels, “the river” was an ominous presence, sighted by characters as they squinted through storm grates, or smelled by them as they hunched their backs against the night drizzle. The narrator in David Copperfield described walking in a “dreary” neighborhood made more “oppressive, solitary, and sad” by the “dark glimpse of the river.” There were neither wharves nor houses on the “melancholy waste of road near the great blank” stretch of water, and “Coarse grass and rank weeds straggled over all the marshy land in the vicinity.” [5] [8] Along one track, “carcases of houses, inauspiciously begun and never finished, rotted away. [By] another, the ground was cumbered with rusty iron monsters of steam-boilers, wheels, cranks, pipes, furnaces, paddles, anchors . . . and [he knew] not what strange objects . . . having sunk into the soil of their own weight in wet weather.” Ribbons of slimy gaps and causeways, “winding among old wooden piles, with a sickly substance clinging to the latter, like green hair . . . led down through the ooze and slush to the ebb-tide.” The narrator was reminded of an old story about the place, “that one of the pits dug for the dead in the time of the Great Plague was hereabout; and a blighting influence seemed to have proceeded from it over the whole place. Or else it looked as if it had gradually decomposed into that nightmare condition, out of the overflowings of the polluted stream.” [6] [9]

Here we had the detritus of an industrial society — the rusted-out hulls of “iron monsters” — as well as the medieval ghosts of plagues from the past haunting Copperfield’s river. The disease that came by the water to the city of London in the 1830s was an old one, but its epidemic success required the mass society of the modern age and the great commerce of trade and empire that turned the “fine fresh” Thames into a “deadly sewer.” If nineteenth-century economies were particularly productive, they were also wasteful. The stillborn projects of industry left behind sorry images of “blight,” while the waifs who hid inside their “carcasses” were just another form of discarded organic matter by the river’s edge. There was nothing quite so nauseating as a Victorian city center.

London’s Rubbish Wars

Indeed, nineteenth-century London had a problem. By the 1800s, it housed a runaway population of several million residents — none of whom enjoyed indoor plumbing, but all of whom contributed to the city’s sewage crisis. At the end of every day, one-thousand tons of animal droppings littered the streets. Waste in cesspits accumulated literally beneath peoples’ homes. The “better” houses, meanwhile, often had several cesspools beneath their properties, and “when one cesspool became full, it was also customary to arch it over and dig another, ‘to avoid the expense and trouble of removing the soil.’” Some of the best homes in the West End were “literally honeycombed” in their foundations with chambers “full of ancient ordure.” [7] [10] Were we to visit a metropolis like London in the 1800s, most of us would soon faint from the stench — and probably land in a pile of horse manure.

For twenty-three shillings per week (decent pay for such a station) and without any sort of sanitation gear, workers by the name of “night-soil men” shoveled such filth from cesspits into buckets, then dumped their contents onto wagons, and finally carted the slop away to be sold to farmers as fertilizer. It was not uncommon for night-soil men to find corpses in these pits, or — given the hours during which they labored (midnight to five AM), to run across bloody crimes being committed on the streets. Officials often called on these persons to corroborate witness statements at murder inquests. A sordid business, but an indispensable one. It’s a simple thing to say, but an ecosystem — whether it be a rainforest or a large city — only maintains what its residents’ energy input can sustain. The Netherlands, for example, is still today the most densely populated state in the world, because during the Middle Ages its people learned how to compost waste that yielded better and larger crop returns — a feedback cycle resulting in a population explosion in the Low Countries. [8] [11] London too, managed this delicate balance of life and death, food and fuel, and recycled waste. But as the city continued expanding and at a more rapid pace, the costs of plying the night-soil trade also increased. Fertilizer hawkers had to journey longer distances to farmland beyond a city that had breached its old Roman walls centuries ago, then kept sprawling. Night-soil fees hiked upward accordingly, and many London landlords simply let the filth beneath their structures amass rather than pay the professional cleaners to empty them. London’s waste management slowed, while its population swelled; the methods that once served the subjects of Elizabeth would no longer suffice for the subjects of Victoria. London had become an unsustainable city.

Worse, many London cesspools/pits around which these night-soil men worked were designed to be permeable, so that “liquid could percolate from the chamber into the ground below, leaving a more solid sludge behind.” In other words, readers, “they were designed to leak.” In an age during which most people still relied on wells and water pumps, the potential for pollution was all but certain. The vast number of leakages poisoned London’s groundwater and, of course, the Thames. Nevertheless, there was no contemporary science linking bad water to specific illnesses. The invisible world of microbes and bacteria remained unknown. It was once customary for Europeans in ancient Rome and the Middle Ages to avoid drinking straight water. Knowing that alcohol somehow made beverages safer, everyone chose to drink watered-down wine or mead. For a variety of reasons, this practice had declined by the Victorian era. [9] [12] Once the (visible) particles in the water settled at the bottom of one’s glass and the water became “bright,” almost everyone deemed it safe enough to drink. [10] [13]

Almost everyone but do-gooders like 1820s newspaper editor John Wright, who took up a crusade against London’s water companies and the monopoly they wielded over city dwellers. This water cartel zoned the populace into the use of certain pumps or fountains, regardless of health concerns. It alarmed Wright that “during the twelve-month attention [he] paid to the subject,” virtually no one “could point out to [him] the source, whence the impure water which they saw running into their cisterns was drawn . . .” Worse, he revealed the origin of Grand Junction’s water (one of London’s largest suppliers) to be “nearly adjoining to the mouth of the Great Ranelagh Common Sewer.” [11] [14] We have our “War on Terror,” “War on Drugs,” and “War on Common Decency,” but the Victorians had an especially icky “War on Rubbish.” Wright used provocative language and compared customers under this water-racket as “counted out and handed over . . . like so many negroes on a West Indian estate.” [12] [15] His report to Parliament included the testimony of numerous West End doctors, “all of whom preferred to rely on sending their servants out for groundwater rather than make use of their own taps.”

Following Wright’s explosive exposé, a Times correspondent fingered John Edwards, Esq. of Regent Street and owner of the Southwark Water Works as the worst culprit of the monopolistic bunch. All the “filth and all the sewers of London may be said to be constantly rolling from the spot from whence Mr. Edwards takes his supply; and which supply goes down the throats of our good people,” he charged. According to interviewees, the water provided by Southwark looked like “pea soup” in wet weather, “[smelled] like bilge-water and . . . [was chock] full of animacula.” Baths drawn from its pumps were often little better than “liquid mud,” whose scum could be skimmed from the top. [13] [16] Bathers shared their tubs with leeches and tadpoles.

Not everyone was impressed with their muckraking. Skeptics charged Wright of “rabble-rousing” and drumming up “hydrophobia.” Meanwhile, Grand Junction Water assumed the picture of innocence. The company issued marketing material promising that its product was “always pure” and “constantly fresh,” “fed by the streams of the vale of Ruislip.” [14] [17] One sees visions of snow melting its way down the unspoiled Austrian Alps and to the soundtrack of birdsong. Say what you will about the water companies, but that took some nerve. Nineteenth-century newspapers were notorious for melodrama, but everyone could see for himself the disgusting truth of their claims. The conditions Londoners lived with would exact a stiff cost in the decades to come.

[18]

[18]Etching by George Cruikshank, “Salus Populi Suprema Lex [The Safety of the People the Highest Law]: Source of the Southwark Water Works” (ca. 1832); John Edwards, owner of Southwark Water, sits like a triton atop the Thames and salutes the people of London with sewer sludge.

Plagues of Egypt

Cities outside the West were not any better. Writer R. R. Madden had nothing good to say about 1820s Alexandria in his travel memoirs. During ancient times, when they maintained the greatest library in history, a more industrious people had built equally magnificent wells in the city that every year the Nile floods replenished. Now, Madden observed, they were in a state of decay and hopeless silt blockage, though their “preservation [was] most important to Alexandria, [for] there [was] not a single spring in the city or its vicinity.” [15] [19] Time and diluted blood had long ago sapped these people of their vitality. Madden laughed down the myth of Turkish cleanliness in vivid terms:

The Turks are too indolent even to clear those [wells] which are now choked up with mud. It is quite disheartening to see the finest structures, even those which are most necessary to their immediate comforts . . . If the wall of a house crack, . . . they put a mat against the fissure; if it fall, they remove to another wing; if that be threatened, they apply a prop; if the roof tumbles at last, they pitch a tent behind the ruin; and when winter advances [and they] must build another . . . they choose the nearest spot to the old materials, because it is easier . . . for the frieze of a palace to form a threshold; for the sarcophagus of a king to make a bath; or for the broken statue of a god, to fill a space . . . [16] [20]

He noted that the Jewish area was the most offensive quarter. Hebrews seemed to wallow in all manner of putrefaction. Pedestrians could smell them half a block away. Their habit “of depositing every species of immundicity in their narrow streets” resulted in serious outbreaks of plague (the land of the pharaohs should not have allowed these people back). Few Turks or Jews washed their linens, and butchers slaughtered their animals on public avenues. If the blood flow from this practice reached residents’ front doors, “they [swept] it to their neighbours.” Should a visitor in Alexandria have mentioned the word “sewer,” locals would have greeted him with vacant stares. And no one removed dead dogs, cats, or rats from the middle of the streets. When a worse epidemic inevitably hit the populace, would careless natives roll the bodies into the “magnificent” wells — would they bother to remove them at all? Like most colored masses in Near and Far Eastern cities, the only thing they would do capably was die. Then await the next despot or scourge. By the time he’d left Alexandria, Madden had taken to calling it the “City of the Plague.” [17] [21] Whether through “indolence,” overpopulation, careless authorities, or the immoderate habits of the poor, these nineteenth-century cities courted devastation on an increasingly industrial scale and with an increasingly efficient and globalized means of travel with which to spread epidemic illnesses. The biggest beneficiaries of train and air travel might not have been man, but microbe. Sour water everywhere.

3. The “Gift of the Ganges”

Predictably, the worst epidemic disease of the nineteenth century originated in the East — in 1817 India, near the port of Calcutta. A less contagious variant had periodically emerged from dormancy and stricken hotspots on the Subcontinent for hundreds of years. While the Portuguese were busy establishing bases of trade on the Indian coasts during the 1500s, a Portuguese physician named Garcia da Horta mentioned in his records a disease that he called mordechim; judging from his description of the illness, it could have been nothing other than what we now call “cholera.” [18] [22] Indians simply called it “Spasm.”

According to Indian lore, the legendary King Vikrama subjugated cholera and buried it far underground. But the British, believing that the burial place concealed a vast store of treasure, excavated the area and released the cholera-demon once more. All epidemics have bred conspiracies and tittle-tattle of this kind, but the British knew better. Hindu practices involved “holy bathing” in the Ganges, a large river forever contaminated with every kind of organic filth. India was synonymous with disease. Lord Moira, the Marquis of Hastings and leader of the British East India army, was therefore not entirely shocked at the sudden sickness that seized his men that year. On November 13, 1817, the general recorded in his logbook that a “Dreadful epidemic disorder . . . [had] broken out in camp. It [was] a species of cholera morbus, which appears to seize the individual without his having had any previous sensations of the malady. If immediate relief is not at hand, the person to a certainty dies within four or five hours.” [19] [23] Given the realities of imperial sea traffic, it was only a matter of time before cholera moved west and ravaged the European peninsula.

The cholera morbus pathogen infected the gut of its victims through water contaminated by other victims’ excrement (making the assertion that it first developed in the petri dish of the Ganges River likely). It could live for several days inside the water tanks of ships; could live much longer in the warm waters of a camel’s hump while the animals were engaged in the packing trade from Tartary to Russia; and could live for fluctuating periods of time within the intestines of human carriers who, to all outward appearances, may have seemed healthy. The disease needed only a few of these carriers to remain regionally active.

When victims caught cholera morbus, they suffered the worst experience of their lives. Hardy individuals were suddenly struck as if by a “hammer-blow.” Convulsions and uncontrolled purges of the body led to acute dehydration, which then caused agonizing cramps. Someone young and attractive in the morning became “shrivelled wrecks of bluish skin, sunken eyes, and protruding teeth by nightfall.” [20] [24] A terrifying and humiliating end. Myths “circulated about people who sat down to dinner and died before dessert.” Even after death, their limbs continued to spasm. Because of this post-mortem thrashing, one of the abiding fears that cholera caused was that of premature burial. With no vital monitors, the line separating life from death was much grayer, and tales of “exhumed bodies . . . later discovered in contorted positions, bones broken, skeletal hands wrapped in torn-out hair” [21] [25] filled penny dreadfuls and inspired some of Edgar Allan Poe’s most disturbing stories. Fifty percent of the cholera-afflicted died, while those who survived often suffered from permanent disfigurement and speech impediments. Given the atrocious sewage systems in most nineteenth-century cities, King Cholera was poised on the warpath to an easy victory.

[26]

[26]The “Blue Terror”: A French illustration of a twenty-three-year-old woman before and after cholera (ca. 1832)

Cholera Comes to Britain

Since the Marquis of Hastings had reported on the sickening of his troops in 1817, cholera had tracked steadily westward into the Balkans and Eastern Europe. Newspapers in countries closer to the Atlantic ran feverish updates, along with a steadily rising death toll. Some in England assumed a manner of “fatuous contempt,” while others succumbed to “extravagant terror.” [22] [27] Could “it be true, each asked the other . . . that whole countries [were] laid waste, whole nations annihilated?” The fields of Hindoostan, “the crowded abodes of the Chinese, [were] menaced with utter ruin . . . We called to mind the plague of 1348, when . . . a third of mankind had been destroyed. As yet western Europe was uninfected; would it always be so?” [23] [28] Hardly. Cholera struck the British Isles in full force by 1831 (and in North America, thousands of infected immigrants arrived on the East Coast by the spring of 1832). An atmosphere of hysteria prevailed in England as authorities began to paste signs onto alley walls and street corners that described in graphic detail the epidemic’s symptoms. Morbid humorists began selling prayer-card talismans with “NEW & CERTAIN antidote to the CHOLERA MORBUS” scrolled across their tops. Another, more earnest fellow, who claimed to have lived in the East Indies for over three decades, offered his experienced opinion by sending a recipe for cholera medicine to his local newspaper: “Two fifths absinth, one fifth elder tree flowers, one fifth mint leaves, and one fifth liquorices.” [24] [29] The worst cup of herbal green tea that one could imagine. Meanwhile, learned men of science had no idea what to suggest.

In one of Britain’s episodes of Polish white-knighting, a letter from “Laertes” to the London Times blamed the spreading of cholera on Russia and “that serene, but I fear very cold-hearted prince, the Emperor Nicholas.” [25] [30] The disease in that enormous country killed one million Russians (possibly more), including celebrated composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky at the end of the century (1893). “The Blame Game” continued to be a popular pastime — as it turned out, cholera had just as many perpetrators as it did victims.

Along with one of the richest autocrats in Europe, the poor slum-dwellers and peasants were supposedly at fault. In the tone of an exasperated schoolteacher, an Oxford Board of Health placard read: “All Drunkards, Revelers . . . you are now told for the third time, that Death and Drunkenness go hand in hand . . . Death smites with its surest and swiftest arrows the licentious and intemperate.” [26] [31] The burdensome underclass was ground zero for the cholera threat in England. They threatened to drown everyone in the Thames’ oozy undertow, to strike down the most talented and beautiful specimens of the age due to their dirty habits. And because epidemics have always by nature been social phenomena, the threat of social contagion — of unrest and rebellion — has followed the paths taken by medical contagion. [27] [32]

Rumors of conspiracy began to fly, and bargains with God intensified. Wise men and experts tried to talk themselves out of crisis while Rome burnt around their ears. Cholera had a significant impact on France, for instance, serving as the backdrop for Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and as the cause of General Jean Maximilien Lemarque’s death in 1832. [28] [33] The subsequent rebellion against King Louis Philippe featured anti-monarchists in Paris and arch-monarchists outside the capital. The cross-dressing Duchesse de Berry — a woman (only four-and-a-half feet tall) who disguised herself as a peasant boy — led a revolt that would have restored the Catholic Church and the Bourbon Dynasty to their rightful places atop French society. It would also have placed her own son on the French throne. Cholera was a political disease.

In overwrought prose, Dr. David Kay elaborated on this point and linked the social and biological as dual contagions:

The invasion of [this] pestilence . . . unmasks the evils which have preyed upon the energies of the community. He whose duty it is to follow in the steps of this messenger of death, must descend to the abodes of poverty . . . where pauperism and disease congregate around the source of social discontent and political disorder in the centre of our large towns, and behold with alarm, in the hot-bed of pestilence, ills that fester in secret, at the very heart of society. [29] [34]

Infected bodies led to an infected body politic.

But the common folk had their own ideas about whom to blame, chief among them the “commercialists” who flaunted quarantine and trade restrictions (and who also insisted that the disease was simply a manifestation of the “old English fever”), as well as the professional class of politicians and medical men — the group we today would call “the elites.” In terms of the colorfully bizarre, France again took the cake. At night and during the terrible spring of 1832, Paris’ elite attended extravagant masquerade balls (“cholera waltzes”) to thumb their noses at the plague sweeping their nation. An American journalist invited himself to one of these balls, and he described seeing a man costumed as Cholera, himself: “skeleton armor, blood-shot eyes, and other horrible appurtenances of a walking pestilence.” [30] [35] Occasionally, a reveler would peel off his mask and reveal a purpled face, then collapse of sudden onset cholera. Death came so quickly, that many were buried in their costumes. The thrill of flirting with death wore off, and as “the gay dance vanished, [and] the green sward was strewn with corpses . . .” [31] [36] Poe’s cholera-muse gifted him with yet another flash of inspiration. [32] [37]

If Parisian elites were said to be reckless, then upper-class Britishers were said to be nefarious. Ever since the passage of the Anatomy Bill of 1828, which stipulated that the bodies of the destitute and of workhouse inmates should be given to medical schools, the people of Britain suspected foul play. Conspiracies that officials meant to turn every body they could get their hands on into “anatomy soup” proliferated — and with cholera killing Britons by the hundreds and thousands, such whispers and rumors grew louder.

By March of 1831, John Hase, a laborer of Manchester, had lost both his son and daughter-in-law to cholera. Now, his three-year-old grandson had fallen ill. Having little choice in the matter, Hase bundled the boy up and had him admitted to the local hospital for treatment. After a few days, the doctors assured him that the boy was doing much better and was on his way to recovery. But when Hase next arrived at the hospital to visit, the doctors “gave [him] the ol’ runaround,” until they finally admitted that the toddler had died. [33] [38] An enraged Hase was convinced that it was murder — that hospital staff wanted another corpse on which to perform their ghoulish experiments. He gathered together some local toughs and concerned citizens, stormed the hospital, and then dug up his grandson’s coffin in the cemetery behind the building. When he opened the casket’s lid, Hase found that a brick had been substituted for the boy’s head. Imagine the outrage! A protest ensued that made ordinary Britons — already paranoid and stretched thin from the epidemic — into rebels. They “freed” other cholera patients from the hospital’s clutches, marched onto the government district, and then had an old-fashioned riot. Only with the army’s help were Manchester officials able to disperse “the rabble.”

After disasters like this throughout England, authorities knew that enforcing significant hygienic and lifestyle changes on the working-class was also courting social disaster (measures that, at the time, seemed to have had little mitigating effects on cholera’s spread). The public would only accept so many restrictions for so long. City councilors whose unenviable duty it was to carry out the prescriptions of the recently passed Public Health Acts, found themselves on the financial hook. Courts awarded damages to plaintiffs whose property interests were at odds with sanitary measures, and their compensation came directly out of councilors’ pockets. The interests of the common good ran into the brick wall of twelfth-century Common Law. The historic rights of free-born Englishmen made them a proud and capable people; they also made the securing of compliance with (half-hearted, anyway) cholera policies a task more difficult than the herding of England’s feral cats.

[39]

[39]An 1883 American cartoon (the disease hit the United States as well, through trade and less-than-vigilant screening of immigrants) showing the guardians asleep on the job while ghastly Cholera has its way with the city.

Misadventures in Tuscany

Even in places that did not enjoy the Anglo-Saxon tradition of Common Law, the common people fought bitterly over cholera policy. There were few places where popular resistance against plague authorities was greater than in the Italian state of Tuscany. Cholera struck the region most severely in 1835-37 and again in the mid-1850s. During the latter outbreak, eighty percent of the Tuscan communes were affected, and 56,730 cases registered (nearly two-thirds of whom died). In the 1850s, Italy had not yet unified, and a Grand Duke ruled the territory — a cousin of the Medici line and one with close ties to Spain. But throughout the nineteenth century, Italy became embroiled in liberal and nationalist uprisings that targeted autocrats like the Tuscan Grand Duke and the Austro-Hungarian emperors who maintained control of much of the north. Authorities were therefore sensitive to local defiance of quarantine and isolation policies. Even at the height of cholera’s grim chokehold over the province, Tuscan officials relied more on “suggestions” and milquetoast public education campaigns rather than outright coercion.

Unlike the British, Tuscans often had to endure a scarcity of water — especially during the hot summer months, when the country creeks dried in their beds (and during the season when the pathogen was at its most virulent). This fact did not help the water sanitation issue, for the rivers and streams that did exist were inevitably overused and — as in Britain and France — hopelessly polluted. The waters in the only public bath in Florence, for instance, were “turbid with human feces, owing to the bath’s location just below the site where the central sewer emptied into the River Arno.” A perfect channel for spreading what the French called: “le mort de chien.”

“Contagionists” and “anti-contagionists” were at loggerheads when it came to cholera policy. At various points, medical advisors in Tuscany attempted to enforce a quarantine and sanitation cordon along the borders. They introduced compulsory notification for “all suspect disease cases,” set up isolation hospitals, and provided free healthcare. Some city governments posted guards outside cholera-stricken residences and attempted to crack down on local tradesmen. Many places restricted the importation of food into cities that might have been spoiled or otherwise “unhealthy,” making the food shortage more acute. [34] [40]

Given the beliefs around the anti-contagionist “miasma” theory, eliminating putrefaction became a paramount concern. Even though these ideas were nebulous and not exactly accurate, they did promote the improvement of waste removal — from the prohibition of rotten fruit, to the clearing of animal dung, to the building of better sewage systems. The Tuscan tradition of funeral rites also received notice. Before cholera, it was customary for relatives to bury the dead in shallow graves behind a churchyard for several days. Then, they unearthed the bodies, scraped away the remaining flesh from the bones, and finally interred them in communal tombs. According to one parishioner, the stench was staggering:

There [were] only a few crypts in the church, which [were] filled already; thus, when a new corpse [was] laid to rest, the other corpses [had] to be shoved together with a piece of wood, in order to create space for the new one to enter. [35] [41]

Bodies, in other words, were piled and shoved together like rotten cordwood. This could not go on.

But as it happened, passage and implementation of sanitation laws were two different tasks. New liberal politicians helped pass health codes, then were reluctant to carry them out, lest it curb anyone’s liberties. Compounding this lackadaisical response, a conspiracy, not unlike those that swirled around Manchester, swept through the countryside: cholera was simply the upper-class’ latest attempt to kill off the peasants. With the imposition of the trade quarantine, Tuscany’s economy plunged through the floorboards. Food became more scarce than clean water, and prices soared. City-dwellers watched as the wealthy fled their towns and left them behind to suffer the consequences of almost total economic breakdown. Many were convinced that the announcement of the epidemic had been “a false alarm.” Or worse, a poisoning plot.

Wild rumors circulated that physicians received a bounty for every cholera patient they killed, leading to mass underreporting and lower hospital admissions. Leaflets circulated that “called on the poor to beware these evil machinations and that warned doctors” that they would pay for their crimes by being “torn to pieces, or thrown to the dogs.” [36] [42] Mirroring Mr. Hase’s impromptu riot, a large group of protestors in 1835 Livorno surrounded a troupe of guards and began pelting them with rocks. As the guards carried a female victim to a cholera hospital, hoarse cries of “Infamous murderers! You carry her to the slaughterhouse!” [37] [43] Large gatherings and crowded religious ceremonies continued, for authorities didn’t dare cross the Church (indeed, in the nineteenth century, the state played the supplicant to the Church). A hapless city councilman sighed at the futility of it all, for he knew the people’s temper, of “their insubordinate and stubborn character . . . [so he had], for the time being, refrained from any [enforcement].” [38] [44]

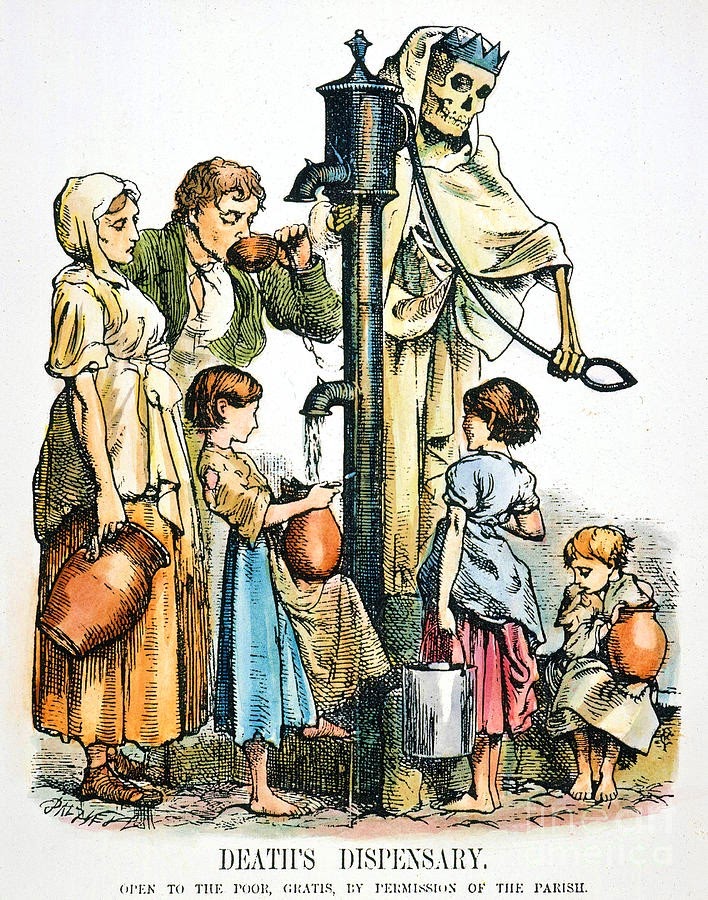

[45]

[45]Drink up, the water’s fine; by the time of this 1866 cartoon, “Death’s Dispensary,” a consensus that contaminated water caused the cholera epidemic emerged among physicians, largely due to the pioneering work of British epidemiologist John Snow.

Conclusion

Fitfully, and over the course of the nineteenth century, urban water systems did improve and became the responsibility of the state, rather than the provenance of private companies. Brilliant engineers designed underground sewer lines that carried bad water away from their cities of origin. But in Tuscany and in England, northern and southern Europe, the cholera experience revealed two of the great truths of modernity (besides the fact that cities are disgusting): “conservatives” and “liberals” both lack the will to solve serious emergencies, or to properly combat their enemies. The conservatives who supported the Grand Duchy’s regime did not engage in the dictatorial methods which they might have, for fear of further stirring popular and nationalist passions. By that time, in other words, they’d lost the strength of their convictions. Liberal politicians meanwhile often seemed too uncomfortable with wielding the kind of power that battling an epidemic like cholera demanded, for their principles were ones of individualist freedom. In other words, their convictions were the problem. Both got in bed with business shysters who would (and did) say anything to avoid a public relations disaster. This crisis of legitimacy, a lack of trust between citizens/subjects and their leaders, led to a black comedy of errors that reinforced the vicious cycle of cholera and its diffusion across the Western world. The illness continued to appear off and on throughout the century.

The other great truth is that epidemics like cholera were almost entirely man-made disasters, even if their plots were not morality-play simplistic. There were plenty of “well-poisoners” to go around. But a sense of compassion and humility here is necessary, because part of the problem was that the nature of the illness remained a mystery for decades. Still, everyone recognized that too much contact with Eastern lands led to imported infestations — since the time of Thucydides, it always had. Most of the natives there were not about to change their repellent practices in their own countries — the real Lost Cause. The US and Canada, also burdened with cholera outbreaks, had lax immigration policies and immigrant health screenings to thank for the thousands of deaths in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. Authorities everywhere knew about but ignored repeated calls to fix urban water supplies until it was too late. For both epidemiological and social reasons, epidemics, once established, are difficult to stop.

Nevertheless, some found cause for optimism. Of all the lessons learned from cholera, one man reflected, “The most important consequences [of the late calamity] are yet future; the improvement we make will either raise or lower the moral standing of every one of us.” [39] [46] While states were less than effective at fighting cholera (at least initially), an ironic consequence of their impotence was a little by little development of the stronger state, fired with the drive of Progressivism. Indeed, in some cases, state impotence became the reason for the more expansive, Progressive state. By the end of the nineteenth century, Westerners had developed cleaner means of waste removal. Their science proved the existence of the microbial world. Whites endured these epidemics and then sought to reform their habits and hygiene — to build better urban infrastructure and to develop medicines that would save future generations from cholera’s devastation. But it also encouraged governments to take a more active role in citizen surveillance/interference, thus beginning the modern supervisor-culture. And despite the changes made to urban living, cities never quite recovered their reputations from the nineteenth century; the “idea of the city as a dangerous place took hold,” and then stuck. [40] [47]

In the meantime, cholera has not vanished. Neither has the Plague. Neither have countless other bacterial and viral pathogens that have afflicted man since his existence. They will return. Epidemics have more often than not emerged from the East, because the populations of South and East Asia (i.e. India and China) have always been large and their personal habits loathsome. It is ironic that our efforts to limit the destructiveness of epidemics through modern medicine have resulted in galloping increases in human numbers — and overpopulation is the primary cause of epidemics. We have ensured the future of diseases by treating them. Progressive eugenicists at the turn of the century understood this.

This brings us back to a crucial point: sustainability and how to sustain the health of the white race and the civilization its people have built after many trials and much loss of life. Why are we spoiling it? As soon as we become unsustainable, as soon as we allow too many of the colored hordes from the diseased tropics into our already overpopulated and declining cities, we court the ancient enemy. If we continue to look the other way as they squat on land won by a people inexpressibly worthier than themselves — then goodbye to all that. Who will maintain the “magnificent wells” and rivers when no one capable is left, when no one cares? It will be a sad day when/if the proud Mississippi becomes the Ganges of the North.

But plagues are also opportunities, for defiance against the long-time poisoning of the common well. After bitter experiences on the river of death, once “dark and mysterious,” a watery grave, we might turn our eyes toward the warm touch on the horizon. As the bridges and “Church towers” on either side spire into an “unusually clear” morning, a veil will be drawn from the river, [and] millions of sparkles burst out upon its waters.” We are “strong and well.” [41] [48]

* * *

Don’t forget to sign up [49] for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [50] Each of the above quotations are from Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend [51] (1865).

[2] [52] Mary Shelley, The Last Man [53] (1826)

[3] [54] Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War [55] (ca. 430-401 BC).

[4] [56] There is a 1990s French film called Le hussard sur le toit [The Horseman on the Roof) that delivers an entertaining introduction to the 1832 cholera outbreak. Juliette Binoche and Olivier Martinez starred as an affluent woman from Aix-en-Provence and an idealistic Italian nationalist who led the resistance against Austro-Hungarian rule. As it turned out, murderous Austrian bounty hunters were the least of their long list of problems in cholera-ravaged France.

[5] [57] Charles Dickens, David Copperfield [58] (1850).

[6] [59] Ibid.

[7] [60] Steven Johnson, Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic — and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World (New York: Riverhead Books, 2006), 5-7, 10.

[8] [61] Refer again to Johnson’s Ghost Map.

[9] [62] One such reason had to do with the demands of industrial wage labor; factory employers, for example, forbid drinking on the job. In these often cramped and closed-in quarters, the new phenomenon of supervision took hold. Everyone would know if an employee came to work drunk. Slaves in the Antebellum South were less supervised..

[10] [63] Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight against Filth (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014), 48.

[11] [64] John Wright, The Water Question: Memoir, Addressed to the Commission (London: J. L. Cox, 1828), 7-8.

[12] [65] Ibid., 21.

[13] [66] “Supply of Water,” in the London Times (May 8, 1830).

[14] [67] Dirty Old London, 52,

[15] [68] R. R. Madden, Travels in Turkey, Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine (London: Whittaker, Treacher, and Co., 1833), 158-160.

[16] [69] Ibid., 158.

[17] [70] Ibid., 202.

[18] [71] Anon., “The International Sanitary Conference,” British Medical Journal (September 1866), 336.

[19] [72] See Sheldon Watts’ Epidemics and History (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1997), 178.

[20] [73] Ibid., 173.

[21] [74] Sonia Shaw, Pandemic (New York: Picador, 2016), 41.

[22] [75] Dirty Old London, 89.

[23] [76] The Last Man (1826).

[24] [77] Maria Antónia Pires de Almeida, “The Portuguese cholera morbus epidemic of 1853–56 as seen by the press,” in Notes and Records of the Royal Society, 66, no. 12 (2012), 54.

[25] [78] Laertes, “To the Editor of the Times,” London Times (May 28, 1831).

[26] [79] Epidemics and History, 194.

[27] [80] Of course, epidemics were always both biological and social problems that then assumed the narrative structure of passion plays: the practices of unscrupulous tradesmen, the dissipated poor, the incompetent elites — led to the intense suffering of the innocent and beautiful. The honest farmer who fed the nation caught “le grippe” and left his family destitute. The lovely maiden was robbed of her youth and future happiness.

[28] [81] See Francois Delaporte’s Disease and Civilization: The Cholera in Paris, 1832 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1986).

[29] [82] Ibid., 186.

[30] [83] N. P. Willis, “Letter XVIII: Cholera — Universal Terror,” and “Letter XVI: the cholera — a masque ball — the gay world — mobs — visit to the hotel dieu,” Pencillings by the Way (New York: Morris & Willis, 1884).

[31] [84] The Last Man (1826).

[32] [85] Based on the stories of Parisian “cholera waltzes,” Poe wrote his macabre tale “The Masque of the Red Death.”

[33] [86] Ibid., 192-193.

[34] [87] Michael Stolberg, “Public Health and Popular Resistance in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 68, no. 2 (Summer 1994), 274, 265.

[35] [88] Ibid., 272.

[36] [89] Ibid., 263.

[37] [90] Ibid., 263.

[38] [91] Ibid., 271.

[39] [92] Anon., “A Short Account of the Origin and Progress of the Cholera Morbus” (London: D. Halliday Printer and Bookseller, 1833), 2.

[40] [93] Disease and Civilization, 65.

[41] [94] Charles Dickens, Great Expectations [95], 772.