Day at the Museum: A Special Guided Tour

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled5,752 words

I’m a recent transplant in this city. And as far as cities go, this one isn’t terrible. We live just over the hill from Erie, one of those giant inland seas carved from North America’s heartland, and it’s like having our own, muted stretch of coast for the quiet. There’s nothing “beachy” about it, for the shell rocks are too sharp, and there’s still a coldness at its core. My red Galveston swimsuit and sandals would seem out of place, even in July. And it was on one of my lazy vacation days last week that my mother-in-law suggested, not a swimming or boating expedition, but a trip to the art museum downtown and up the interstate. She knows someone with connections there; we could get in mask and hassle-free. I like this woman, and this is what girl-friends do on their days off, so I agreed.

Let me begin by saying that the museum in question is one of the more well-regarded institutions of its kind in the United States. And its reputation is an earned one. Dutch masters fill whole wings; Picassos commune with Goyas and Gauguins; medieval tapestries (in remarkable shape — few seven-hundred-year-old textiles could be hung from the walls without disintegrating) cloak their rooms in a reverent hush, while Fabergé pieces salvaged from the last, truly beautiful European monarchy sit in their miniature splendor within rows of cased glass. An illuminated Book of Hours that once belonged to Queen Isabella of Spain lies open to pages of rich color and gold leaf. A magnificent armory room features chain mail from the twelfth century, crossbows and their (huge, nearly as big around as my arm) bolts, full suits of royal armor, and swords of every description — including a broadsword considerably taller than I am. As a person who delights in the deadly arts, I was charmed. All of these exhibits leave their viewers in no doubt that the West was once the most glorious civilization in history, and whites were the most talented creators of beauty, in all its forms. For the most part, I had a good time.

But it was our misfortune that a young-ish art history major gave us the grand tour (no offense to readers with this specialization, but like the majority of people these days with degrees in the humanities, art historians are often insufferable bores when it comes to discussing their chosen fields). Nice lady, but bad taste. When I asked about her favorite art movement, she chose, with that light in her eyes, anxious for approval, “modern art.” And by “modern,” she meant “contemporary,” not Modernist. Because I was raised to have impeccable manners, I waited til I had turned away to roll my eyes. Of course it is. So we did venture into the modern modern wing where we saw spray-painted feminist strollers filled with phalluses, a pair of lightbulbs strategically hanging and dimming from the ceiling (representative of AIDS, I believe), and other feasts for the senses. It was also our misfortune to end on this note. On the drive back, I politely declined a late lunch and instead went home and poured a generous glass of summer sangria topped with seltzer fizz, sat on the porch, and gazed at the somber storm clouds gathering above the Lake. After a bit, I lost the bad attitude and came to the conclusion that though the last batch of “art” I’d just endured was the worst; that indeed, it shouldn’t be in the same hemisphere, let alone the same building, as El Greco and Manet — yes, even though all this was true — there were some standout pieces that nonetheless provided unintentional moments of clarity, and sometimes, even hilarity.

Allow me to tuck my arm in yours and play tour guide, readers, as together we explore our dissolving world at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

1. Lot’s Frau, or Lot’s Wife (1989)

When someone of my worldview considers a Holocaust piece to be the least horrible image hanging among the entire contemporary wing of an art museum, it’s a bad sign. The German artist, Anselm Kiefer, born only months before the Second World War’s end, is not (as far as I can tell) Jewish. But he has absorbed the Jewish hatred of his people and has thus shouldered the postwar White Man’s Burden with unbecoming enthusiasm. That said, this piece does achieve a technically interesting and lifelike effect due to its three-dimensional quality, the canvas made from “oil paint, ash, stucco, chalk, linseed oil, polymer emulsion, salt and applied elements (e.g., copper heating coil)” and “attached to lead foil, on plywood panels.” [1] [3] I could almost walk right into this other-world and onto that muddy road near a train station and its clotted railroad tracks. Trains and train tracks have a particularly compelling quality, for they symbolize, like no other mode of transportation does, inevitability. You might crash or derail; some hustlers might hold your car up for ransom, or a storm may temporarily delay you in the snows. But your direction and destination, they are set — predetermined — long before your decision to book a passage.

Because Kiefer titled the piece Lot’s Frau, or Lot’s Wife, audiences are meant to view this scene as a look backward at tracks that lead toward “death camps” and “bloodlands.” We stand frozen as salt pillars, because we have sunk and stuck in the mud, and we cannot get out. Rather like the fact that the West has for many decades been the hostage of history, as if this was our collective Fate. Or, might we be peering at the “brave new world” ahead, one that we cannot avoid, rather than the one that we left behind; the unstoppable progress into tomorrow, instead of yesterday? It hardly matters, for the trains have gone and our gazes have fixed and we have sagged under the dead weight of this burden into the wet of an equally dead wasteland.

I recently re-read All Quiet on the Western Front, and the absolute stasis of trench warfare struck me the most. [2] [4] Every morning soldiers blinked their sleep-deprived eyes at a weak sun that brought no life, but only a numbing realization that everything was just the same as the day and the week and the month before it, that this would go on forever, that the seasons of change were no more. Who could say whether it was spring or autumn in No-Man’s-Land? Solstices only make sense when there is life to blossom, or leaves to golden. The only cycle was the one of front duty and rest, active combat and billets. It would never end until some misfortune eventually picked each man off, one by one. Behind them “lay rainy weeks — grey sky, grey fluid earth, grey dying . . . and [they] remain[ed] wet all the time . . . The rifles [were] caked, the uniforms caked, everything [was] fluid and dissolved, the earth one dripping, soaked, oily mass in which [lay] yellow pools with red spiral[ed] streams of blood and into which the dead, wounded, and survivors slowly [sunk] down.” [3] [5] The soft earth had become “trampled by the passage of the feet of hundreds of soldiers into a uniquely saturated and bottomless morass . . . Right and left were craters full of black mud and water,” [4] [6] and when they looked down at their “hands,” they too, were “earth, [their] bodies clay and [their] eyes pools of rain.” As viewers of Anselm’s art, neither do we “know whether we still live,” or whether we also are ourselves a part of the science-fictional horror-scape of Passchendaele. We are witnesses to the fallout of the World Wars — the Europe into which the artist was born; we too, feel the salt rubbed into the wounds of the pockmarked earth.

Anselm meant for us to picture the Holocaust. Indeed, a holocaust is what we see.

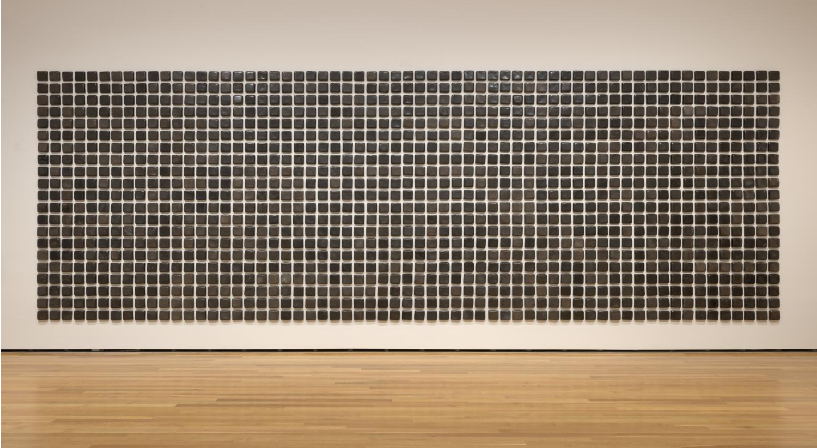

2. El manto negro, or The Black Shroud (2020)

At first this might look like a monochrome mural adjacent to a subway station; maybe a scoreboard from an abandoned pitch. According to the artist, Teresa Margolles, these are actually 1,600 individual ceramic tiles “hand-burnished with a stone to an almost glass-like finish and then darkened with a traditional firing technique using [the] smoke from burning cow manure.” She “collaborated” with artisans from the Mata Ortiz district of Mexico (100 miles from the US border and in the state of Chihuahua) who in turn sourced deposits of the stuff from the regional mountains nearby. Each tile supposedly “represents a victim of the drug wars that are now rampant [there]; as a grid, they speak to a collective history,” presenting Mata Ortiz “not only as a site that has fallen prey to violence, but also as a site of artistic productivity that prevails alongside hardship.” [5] [8] The usual victim awareness-raising piece that is “brave,” “challenging,” and most importantly, not pretty to look at — the genre that has characterized much of the art scene in recent memory.

I turned to the tour guide with a furrowed brow and asked, “I wonder what she means by ‘victims of the drug wars?’ . . . That’s a little vague.” I received no reply, because questions of contemporary artists (especially colored ones) aren’t encouraged. Did she refer to gang members, coyotes, or sicarios whose poor choices in friends got them gunned down, or worse? Did she mean law enforcement officers, journalists, and the “innocent” civilians caught in the crossfire? The addicts themselves? Few reasonable people would disagree with the assertion that drugs have been one of the worst scourges of our times, even if they disagree on how to resolve the crisis. No doubt the failed state of Mexico has suffered from the violent turf wars fought by that country’s drug cartels. In 14 of Mexico’s 31 provinces, the chances of a murder being brought to trial in the year 2010 were less than one percent. [6] [9] I doubt it has improved since then (justice in El Norte certainly hasn’t).

I was reminded of the story of a man known only as “Andrés,” a drug mafioso who once worked in the sweltering heat of the Colorado Delta for the price of 40 pesos per day. Like the other laborers with him, Andrés wore the sweat-soaked coverings of an oversized long-sleeved t-shirt and faded blue jeans, the full body shields that protected them from the noon-high rays beating down on the mesas below. He spoke softly “from under the brim of his wide wicker hat [and] described how he worked odd jobs . . . sometimes building roads across the desert, extracting gravel, or piling stones and sometimes as a helper on fishing crews.” After a while, the conversation between the men “turned to rumors of the huge wages that one [could] make in the United States.” Andrés complained that Mexican wages “were not fair,” since it was difficult to “find enough work to cover even the basic cost of living.” Soon after dark descended upon the dry valley, the compadres went home, and Andrés went his own way. But a few months later, he showed up again. This time he stepped out in a new pickup truck and “in beige alligator boots, a wide belt with a metal buckle, and a cowboy hat.” There was confusion at first, for he looked so different that few recognized him as the same man. “Who is that?” someone asked, startled. “That’s Andrés,” another answered, “he’s going around all cholo [7] [10] now.” A young woman who’d never before looked at him twice swooned, “he’s soooo handsome.” [8] [11] A popular song came on the stereo about the life of a powerful Sinaloa figure called “El Ondeado.” A few children touched the necklaced icons of Jesús Malverde beneath their shirts, [9] [12] and everyone sang along to the lyrics, “He killed at a very young age! . . . And for this he lived traumatized.” [10] [13] Of course, Andrés had become a narco.

Relatives of “drug war” victims have challenged the Mexican government’s common assertion that those individuals found murdered, hacked to pieces, and left by the road in a pile of soiled bedsheets must have been “involved” in narco-trafficking. Instead, they have vehemently protested that their loved ones had nothing to do with the illegal trade. But this takes for granted the idea that definite lines separate those “involved” from those “not involved” when, like our own porous southern border, no such boundaries in reality exist. Like the locals who regarded Andrés with a mixture of envy and disdain as they all joined along to a well-loved ballad singing the deeds of a kingpin-killer in voices raised in both praise and censure, the interlocked web of socio-economic connections have rendered the distinction between narco and neighbor irrelevant. Once again, who are the “victims of the drug wars?” Take a good look at this bad art. It represents what has happened to an entire population subjected to the most sadistic band of warlords in history; it indeed foretells the coming of a shroud, of “anarchy loosed upon the world . . . The blood-dimmed tide” rises, “everywhere the ceremony of innocence [is drowned]” as the “rough beast” emerges from the desert of our borderlands to uproot and mangle the fertile pastures of our heartlands. [11] [14] The heartland, in fact, has borne the brunt of the opioid-heroin crisis of recent years, and the main suppliers of US heroin are Mexicans, such as Andrés’ employers. Multiply these 1,600 ceramic tiles by an order of 60 and readers might have an idea of the vast number of U.S. overdose victims killed each year because of this epidemic. Mexican caravans aimed toward the Rio Grande have claimed they were “bearing a message of pain,” to bring to the American people, the guilty passport into our nation with which to shame and impress the gringos. [12] [15] But we have our own pain. The way must be shut!

Speaking of which —

3. Metal Fence (1991)

I am assured that elusive installation artist Cady Noland, whose works explore “the ideals and symbols of the American Dream,” [13] [17] has a fanbase obsessed with her: “billionaire collectors, mega-gallery founders, powerful museum directors, [groupies] who trek to her every show like Deadheads.” She uses “ready-made” art combined with trash, photos of famous people, American flags, handcuffs, pistols, bars, and “other instruments of torture.” [14] [18] These are her “brawny, muscular responses to the American mythos set against the totems of oppression — fences that keep out immigrants, barricades to enforce brutality, holes that evoke the victims of gun violence.” [15] [19] Nevertheless, she once threatened to shoot a museum director who planned to show her work without her permission and has had nasty personal spats and court battles with art dealers over “restoration” of her pieces. She has perhaps internalized the quick-draw Yankee temperament and our resort here to both violence and litigation despite herself. It’s unclear whether this Metal Fence pictured above and featured next to Lot’s Frau and across from El manto negro was something Noland constructed, or if she merely removed a portion of chain-link rail that a man had once made to keep the coyotes away from the calves.

According to the museum, Noland used the aesthetic language of sixties’ minimalism, when mass-manufactured items began to be introduced into art, “to subtly question America’s founding principles and ideals. Consisting of a simple chain-link fence with an opening, this work invites reflection on the politics of exclusion.” [16] [20] Nothing says “subtle” like a giant sculpture of twisted steel wire with the words, “AMERICAN EXCLUSION” beside it. Of course, with the large “opening” in the middle, one wonders whom exactly the Metal Fence would exclude. Single-file as you’re crossing the border please, hombres. The last time I checked, my little exclusive hometown of 120,000 people was now home to over 54,000 Asians, 14,500 Hispanics (the number on the official books, anyway), and 10,200 blacks, including those from Africa and the Caribbean. Whom are we excluding, Ms. Noland?

And if I may mince words and play semantic games, “fence” and “wall” are two slightly different things with subtly different functions. The latter is a vertical structure, often large and made from brick and stone, that physically divides an area; the former is also a vertical structure, more often made from wooden posts and wire, and that physically encloses an area. Both can certainly exclude outsiders, the one projecting power and the other property rights, but the “fence,” because it is an enclosure, can also be a pen of safety, or a prison of inmates. With such penetrable borders, so many “openings” that exclude no one, I, and I’m sure many reading this, have felt as if our nations had instead enclosed its native whites in a multicultural madhouse from whence it has become difficult to escape, even when venturing far out toward the hinterland. Such fences are crueler, for they often mangle, catch, and trap those within; my mind returns again to the Western Front and the “sickly bundle[s]” of shattered men who often hung on their own wire, their “putrid flesh, like the flesh of fishes,” caught on a hook-line that “gleamed greenish-white” through the rents in their uniforms. [17] [21] Indeed, we are now living the unenviable reality of countries with no walls and many fences — enclosure without proper exclusion applied. And all of these no-walls have ironically made us feel alienated and divided from our birth-nations, to which we should rather cling and love. Very cruel. For these reasons too, walls and fences put to their proper uses, they are necessary things that do much more than simply ban.

I was unfair. Noland did inspire some subtle reflection on the “politics of exclusion,” after all.

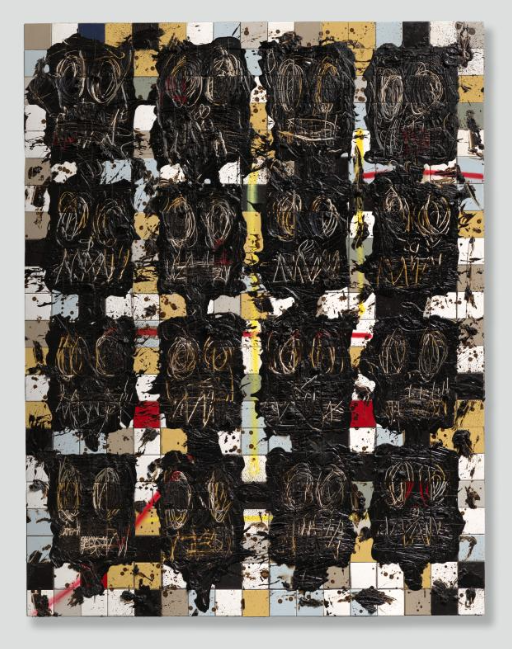

4. Color Men (2015)

Because skin color cannot be washed or wished away, Rashid Johnson has used black/brown soap and wax to represent the smashed faces of black men on ceramic tile. According to the museum’s description, Johnson “draws on a wide range of media and art historical traditions to explore the lived experiences [redundancy] of Black men in America.” This particular piece belongs to a series that began as an “exploration of the artist’s own anxieties and evolved to express the [ordeal] of young Black men during a period marked by police violence and mass incarceration.” In the artist’s words, revelatory of both the self-indulgence and fatuousness of his racial brethren here in the States, “I . . . realiz[ed] that my anxiety was not mine exclusively.” [18] [23] Indeed, given violent crime statistics, it was other “young Black men” “exclusively” who should have caused him his sleepless anxiety.

Of course, we see the resemblance between Color Men and smeared excrement on a bathroom floor. While this was not the Rembrandt or Renoir that I had in mind when agreeing to tour the art museum last week, at least it was not black Achilles, or some insertion of blackness into an otherwise aesthetically pleasing white scene; at least it was not Déjeuner sur l’Herbe with black luncheoners leering over a naked white woman. Here, black men are the dog feces scraped from one’s shoe and left behind to gather flies, or for some unfortunate soul to mop up and bleach away at the end of an equally shabby day. If this was we saw them, or how they saw themselves, instead of viewing “color men” as the heroes to whom we seek to pay admiration at sporting events, or icons to whom we should curtsy on demand, or martyrs to whom we must build urban shrines, the country would become a safer and more honest place.

But we’ve chosen to flatter them, if only to avoid being impolite.

Somewhere in the South and during “Year Eight of Franklin D. Roosevelt,” a young white girl at Woolworth’s candy shop read the sign on the counter: Tar Babies, 20¢ / lb. Inside the bin was a mountain of little licorice candies shaped like pickaninnies. In the summer sun, sultry and blinding, she could squish them sticky between her fingers, til they could double the images of Color Men as tar-black smears on the hot pavement. Everyone privately referred to them as “nigger babies.” But the girl’s granny had taught her that a lady could never use that word and remain a lady. In fact, her granny “wouldn’t even use the word ‘tar.’” And so in order to avoid “hurting the feelings” of the blacks at the other end of Woolworth’s segregated lunch counter, she would call out: “Do you want some babies to eat at the movies?” The blacks looked up at the older woman curiously, and for the little girl, it all fell into place. Granny was “an arch-segregationist with perfect manners; it’s all right to segregate people as long as you don’t hurt their feelings.” Furthermore, “it is much better to be known as a white cannibal than as white trash who uses words like, ‘nigger,’ because to a Southerner it is faux pas, not sins, that matter in this world.” [19] [24]

This was no anti-Southern screed, but a recollection that unflinchingly explored the humor, tragedy, and beauty of a biracial and bygone era. “America,” this anti-cosmopolitan memoirist argued back in the 1980s, “is the only country in the world where you can suffer culture shock without leaving home.” And this instinct to soothe black egos and retain respectability among our peers, even as “arch-segregationists” in the South have since morphed into diversity cheerleaders ensconced in their gated neighborhoods and private schools, shows a pervasive white failing. We’d rather sacrifice other whites than look bad, than to call blacks what their behavior makes them: the stains on America’s dirty underwear. Thankfully, Mr. Johnson has done the uncomfortable and impolite work for us.

5. Las Meninas (2019)

As readers may or may not know, Las Meninas by Diego de Velázquez y Silva (properly pronounced with the high Castilian “lisp”), painted for the court of King Philip IV of Spain in the mid-1650s, is one of the most celebrated, discussed, and dissected works of art in Western history. It depicts a deceptively complicated scene, one surrounding the Spanish Infanta (later Empress) Margarita María of Austria, her ladies-in-waiting, a (very patient) dog, a midget, and several other figures in a pool of sunlight — or alternately, fading into shadow with half-whispers on their lips. On the other side of the young Infanta is the artist, revealed as the virtuoso himself as he steps from behind his canvas, holding a palette of colors in one hand and a brush in the other. He has a double-key of the Chamberlain and Bedchamber on his person, a sign of his significance and value to the royal household, as well as the Badge of Santiago on his breast, perhaps painted there by King Philip himself after Velázquez’s death. [20] [26] The brilliance of the artist is shown when one sees that he was painting through an ingenious method — by way of the crystalline brightness of a mirror also illustrated at the rear of the gallery and facing the viewer; and in the mirror, we can see the reflection of his patrons, the King and Queen of Spain. On either side of the walls, Velázquez reproduced various artworks hung in the apartment, and though dim, clearly they were from Ovid’s Metamorphoses made by Rubens and Van Dyck. [21] [27] José Nieto, the Queen’s Chamberlain, stands in an open doorway leading up to a staircase and letting in some light for the artist. The depth seems great due to the flooring and windows done in diminishing size. The result is both intimate and theatrical, a portrait piece and a piece of action.

As one near-contemporary put it, “there is no praise which can match the skill and taste of this work, for it is reality and not painting.” Velázquez finished it in the year 1656, “leaving in it much to admire and nothing to surpass.” When Luca Giordano (an Italian Baroque master of the seventeenth century) came “and got to see it, he was asked by King Charles II, who saw him looking thunderstruck, ‘What do you think of it?’ And he said, ‘Sire, this is the theology of painting.’” [22] [28] Since that time, Las Meninas has been analyzed and appropriated by everyone from Jacques-Louis David to Michel Foucault. [23] [29] And now, apparently, by Simone Leigh.

[30]

[30]The original Las Meninas [Ladies in Waiting], by Diego de Velázquez, 1656; located at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid

The only connection this colored Las Meninas has to the original is the vague outline of the Infanta’s skirt. Apart from that, the only two reasons why Leigh entitled this piece after the master’s was to 1) attract unearned publicity by grabbing onto Velázquez’s seventeenth-century coattails and allude to one of the most famous touchstones in Western art history; and 2) simultaneously profane the great work to which she faintly gestures, and pervert the lustrous blondeness of the princess and the grandeur of the Spanish court to one of black disfigurement. I was halfway consoled by the fact that gallery visitors took one look at the sculpture with flat, uninspired (or slightly terrified) glimpses; then, when they realized that a small print of Velázquez’s Las Meninas hung nearby for reference purposes, they gathered ‘round it with sparkling eyes and began debating its meanings and merits. Hope for us, yet.

The problem is not politics in art per se (it would indeed be difficult to find an absolutely apolitical work of art); art can be “political” without being polluted. Today’s post-modern offerings hanging or hanging out in our museums are all but guaranteed to be tossed out by posterity. If colored people inherit the earth, they won’t want them. What use would they be? Apart from a security guard or two, I can’t remember the last time that I saw a black person in an art museum; such things are Western inventions. Before Europeans took an interest in them, Egyptians were content to cede the magnificent tombs of the pharaohs to grave robbers looking for gold, to let the evidence of this ancient society remain underground and forgotten. In general, a sense of awe and curiosity are lacking in the non-white world. They have rarely broken through the fourth wall of history, content to live their present-oriented lives as if they were also a part of the landscape, a never-ending cycle, never running towards anything, never meeting, like Velázquez, the stare of tomorrow with a look of challenge, of awareness. If white people grow out of this unattractive adolescent rebellion against adults from the past (and I believe we will, because we must), they will do the sane thing and drop these pieces of dreg-swill into a volcano.

Then the dismay, too, along with the ugliness, will “fly away as the dust, when [we] stand once again beneath the poplars and listen to the rustling of their leaves,” when we gaze at the twinkling Lake in the far distance. It “cannot be that it has gone, the yearning that made our blood unquiet, the unknown, the perplexing, the oncoming things, the thousand faces of the future, the melodies from dreams and from books, the whispers and divinations of women; it cannot be that this has vanished in bombardment, in despair, in brothels” and in the pictures that sit among treasures like shrapnel. Some time soon, where are all is “gay and golden,” the shifting of a season passes like summer rain, “the berries of the rowan stand red among the leaves, country roads run white out to the sky line.” Listen and there is a “hum like beehives with rumours of peace” and whispery shimmers of beauty that is, once and future again, our inheritance. [27] [34]

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [35] Taken from the description on the Cleveland museum’s website, “Lot’s Wife [36].”

[2] [37] It also struck me how “school-like” (in a corrupted sense) this manner of warfare was — in the obvious way that the characters were literally classmates, but also in the structure of homosocial trench life. Soldiers, like students taking a block schedule, spent several weeks at the front, then recessed to a period of rest behind the lines; occasionally, they went on “holiday” furloughs back home to see their families. Its familiar rhythms must have seemed all the more surreal and jarring for that.

[3] [38] Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front, trans. A. W. Wheen (New York: Random House, 2013), 209; originally published in 1928.

[4] [39] Quote from the account [40] of Gefreiter Phuse of the 1st Machine Gun Company, Infantry Regiment 164 at the Battle of Passchendaele (1917).

[5] [41] Taken from the description on the Cleveland museum’s website, “El manto negro / The Black Shroud [42].”

[6] [43] See Shaylih Muehlmann’s When I Wear My Alligator Boots: Narco Culture in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 180.

[7] [44] “Cholo” roughly translates to “like a gangster.”

[8] [45] When I Wear My Alligator Boots, 2.

[9] [46] In that part of the world, Jesús Malverde is the patron saint of narcos.

[10] [47] When I Wear My Alligator Boots, 85.

[11] [48] Quoted from W. B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming [49],” (1921).

[12] [50] An August 2012 caravan from Mexico sought “asylum” in the United States, many in the group claiming that they were “victims of the war on drugs.” They were coming with a “message of pain” to bring to the American people so that the American people would in turn accept these pitiable “victims” as an added burden on their infrastructure, state land, and tax rolls.

[13] [51] From “Artist Biography and Facts: Cady Noland [52].”

[14] [53] Nate Freeman, “Galerie Buchholz Literally Turned Over Its Keys to Cady Noland to Land an Ultra-Rare Show of New Works by the Deeply Private Artist [54],” in ArtNet (June 22, 2021).

[15] [55] Andrew Russeth, “This American Life: Cady Noland’s Art Feels More Prescient, Incisive, and Urgent Than Ever [56],” in ARTnews (March 27, 2018).

[16] [57] From the description on the Cleveland museum’s website, “Metal Fence [58].”

[17] [59] Ernst Junger, The Storm of Steel (New York: Howard Fertig, 1996), 21; originally and privately published in 1920.

[18] [60] From the Cleveland museum description, “Color Men [61].”

[19] [62] Florence King, Southern Ladies and Gentlemen (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975), 11-12. As a “professional misanthrope” and “unreconstructed southerner,” King wrote several humorous memoirs of her upbringing and adult life. When Woolworth’s five-and-dime closed for good, she reminisced not only about the candy there that “overpowered” everyone in “an aroma of hot sweetness” year-round, but also “the orgasmic transports that retailers today call a ‘shopping experience,’” like the one “on December 8, 1941 . . . when a man began smashing everything” in the place “stamped ‘Made in Japan.’ No security guards converged on him and no one worried about lawsuits. As the crowd cheered, the manager winked and said, ‘I needed to get rid of this stuff today anyhow.’” Gone with the wind, indeed.

[20] [63] Dating from the twelfth century, the Order of Santiago is one of the most renowned religious-military orders in the world and owes its name to the patron saint of Spain, “Santiago” (St. James the Greater), originally established to protect pilgrims and further dedicated to the removal of the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula. Since its membership was not restricted to nobles of Spanish origin, many prominent Catholic Europeans became defenders of the Order. Its iconic insignia has appeared often in Western art.

[21] [64] Spanish and Dutch painting was quite entangled and the masters of each region were close colleagues during this period due to the Spanish Hapsburg presence in the Netherlands from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries.

[22] [65] Antonio Palomino, Lives of the Eminent Spanish Painters and Sculptors, Nina Alaya Mallory, trans. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 166.

[23] [66] David, though an admirer of the technical genius of Velázquez’s work, was a Neoclassical master and considered the “naturalism” of Las Meninas to be a slight failing (as the Neoclassicists considered Baroque art — soft and too feminine); for his part, Foucault wrote his oft-cited 1964 essay on Las Meninas in Les Mots et les Choses.

[24] [67] From Nadiah Rivera Fellah’s “Simone Leigh: The Artist’s Las Meninas Acquired Last Year Invites Examination of the Relationship between Artist, Subject, and Viewer [68],” The Cleveland Museum of Art (Fall 2020).

[25] [69] Ibid.

[26] [70] And, it must be said, black New York, Haitian, Nigerian, South African, and Brazilian peoples are all quite different and most outside America would probably be bewildered at Leigh’s depiction of themselves in her Las Meninas as a universal representative of the “Black female body.”

[27] [71] All Quiet on the Western Front, 214.