“All the Devils Are Here!” The Great Storm & Shipwreck Story

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled6,074 words

It was a dark and soon-to-be stormy night on the Gulf Coast some years ago, when my other half and I sat on our porch chairs, gazing toward the sea. He held a cigarette — a bad (thankfully short-lived) habit he’d picked up during his year-long research sabbatical in Valladolid; paired with his fedora, I’m sure he knew that it lent him a (pretentious) air reminiscent of interwar Europe — a period of relative calm before a category-five storm leveled the Western world. And with that combination of dread and exhilaration only wars and tempests call forth, we, too, were waiting for a hurricane as it made its slow approach toward our little bungalow.

“Maybe we’ll get lucky and keep our power,” he ventured. I rolled my eyes a bit at this Yankee (i.e. hurricane virgin) optimism. With a supremely wise, twenty-five-year-old affectation, I plucked the cigarette from his hand and took a long, slow drag.

“Do not indulge for a tiny instant in that fantasy,” I replied. “Whatever happens, it will happen in the dark. In fact, the power will go out before the storm really arrives — a final warning.” Again, we gazed at the sea, waiting for the temporary collapse of our little corner of civilization to begin.

Storms have played significant roles in American and Western history. The so-called “Protestant Wind” of 1588, violently churning the north Atlantic, scuttled Philip II’s Spanish Armada and saved England from invasion. And in turn, the Great Hurricane of 1780 all but wiped out the British fleet in the Caribbean, ensuring that it could not harass American revolutionaries to the north. The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 sent the island to the bottom of the sea, a disaster from which the city never recovered. The once-booming port is now but a small and beloved appendage of hegemonic Houston, and there it will remain. We formulate scientific laws and pore over meteorological charts in order to predict Nature, but the reality is that the universe is unreliable. This then, is what storms and their wrecks symbolize. Build your unsinkable ships and embark on your ambitious quests, mortals, but know this: sooner or later “your land shall be desolate and your cities waste.” [1] [2] (Lev. 26:33) Behold and despair the ruins the cosmos has wrought of your pride.

Throughout history, Westerners have been willing to risk death and disgrace for mobility. Speed and discovery have come at a high cost we seem always willing to pay. We think nothing of driving collapsible aluminum cans at absurd velocities in order to get places faster and more comfortably. We take plane rides across oceans and continents while cruising 35,000 feet above land. The White Star Line’s notorious track record has not prevented people from booking a passage across the sea. Disasters in space should not dampen our resolve to send men to the stars. [2] [3]

And in literature, storms and shipwrecks/traveling disasters often originated with characters who longed to transcend their metaphorical and physical limits. So, the literary and historical sea voyage has been a metaphor for the journey of life in which voyagers “traveled across dangerous waters in a fragile craft of their own design, an image that suggested a community and the social conventions that held them together.” Such travel narratives have been about both alienation and communion. Though the initial voyage and storm usually isolated characters, separating them from their friends and relations, the shipwreck narrative was also about community — about the ties that bound, that moored and anchored our lives. The Mayflower Compact that established one of the first white communities in North America was drawn up and signed before anyone disembarked the ship — a social commitment made possible by the wooden planks and furling sails that literally held the Calvinist travelers together. Americans should remember that for most of our colonial period, the wild “frontier” was not merely or mostly “the west,” but it was also the sea — the vast Atlantic journey all of our ancestors at some point risked. Even today, we use seafaring language to describe our landed existence: our leaders are “pilots” and “captains” of our “ships-of-state”; our troubles are the “shoals” and “rocks” on which we sometimes flounder and that threaten to run us aground; we “beat on,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald once put it, “boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly” into the waves. [3] [4] Death, too, is often described as setting sail for other shores and into the sunset. As far as death goes, it’s a pleasant picture.

But we should not forget that the ocean is also the place that holds all the great human fears within its depths. The dark unknown. After the bow of the Titanic broke free from the stern at 2:00 AM on April 15, 1912, it plunged toward the seafloor at nearly thirty miles per hour — and still it took five minutes for the nose to hit bottom. A dreadful dive putting the wreck and its victims beyond human recall. Even though we have filled in the blank edges of the map with comforting names and definite ends, in many ways the ocean might as well be an infinite space filled with monsters (ocean beds remain the only places on earth humans have not fully explored — and most of us are okay with that). The speaker in T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock likened his existential crisis to “a pair of ragged claws / Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.” [4] [5] Indeed, oceans still swallow people and their craft all of the time and without a trace. The thought of drowning elicits an instinctive horror within us just as it did for Richard III’s Clarence when he dreamed of his own death by drowning (a fate he did in fact suffer at his brother’s hands, when Richard ordered him held upside down and plunged face-first in a barrel of Malmsey wine):

O Lord, methought what pain . . .

What dreadful noise of waters in mine ears,

What sights of ugly death within mine eyes

. . . I saw a thousand fearful wrecks,

Ten thousand men that fishes gnawed upon,

Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl,

Inestimable stones, unvalued jewels,

All scattered in the bottom of the sea

Some lay in dead men’s skulls; and in the holes

Where eyes did once inhabit there were crept

As ’twere in scorn of eyes — reflecting gems,

That wooed the slimy bottom of the deep

And mocked the dead bones that lay scattered by . . . [5] [6]

We cannot truly appreciate the kind of courage it took Christopher Columbus to stake his life and reputation on an untried conviction that his ship would reach China before he and his sailors went mad, or starved. Whatever nightmares of “fearful wrecks” and “dead men’s skulls” haunted early European explorers — and I’ve no doubt that in the quiet moments of the night, they did — faith, honor, and ambition kept those “sights of ugly death” at bay, but never fully banished them.

No, never banished, because while Columbus and Cortés managed to avoid this fate, others, both real and fictional, were not as fortunate. Terrible storms have whipped the waters and dashed countless ships on the rocks. Barring divine intervention, survival in these stories has seemed impossible. Then, at the moment of greatest darkness and desperation, at the moment characters finally gave in to the storm’s power, silence. The survivors opened their eyes and awakened to terra incognita. A fantastic world of bright jewel colors where the old rules suddenly no longer applied (after all, rainbows often follow downpours). A permissive environment — and useful when authors wished to comment on their own societies through comparison. This was where the wild (and beautiful) things were. The shipwreck had both freed and trapped these men on an island of their imaginations, for they somehow knew that danger beyond their imagination lurked out of sight. Just as the storm has signified the human desire-fear of being consumed (swallowed by the sea, kidnapped by the wind, swept away in the flood), the marvelous new world threatened to devour them. Was there treasure waiting to be discovered? Were the natives cannibals? Were there witches there who turned men into swine? Had the heroes been saved, or condemned? The only thing for it was to go and see.

1. Storm-Crash and Deliverance

1780 was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane season on record, and the Great Hurricane of 1780 has no equal. Although its exact track cannot be determined, “forensic” weather detectives have theorized that the storm originated off the coast of the Cape Verde Islands on October 9, then ballooned to colossal proportions. Spanish sailors were the first to spot its formation as it plowed through the atmosphere and barrelled its way toward defenseless Barbados.

One must appreciate that in this earlier age, coastal residents received little or no warning before such cyclones came upon them. We wait for hurricanes; but hurricanes simply happened to our ancestors. This particular storm began “by gentle degrees” and a “light rain,” but even when “the wind arose and the sea began to roar,” still West Indian inhabitants “had no presentiment of the distress and danger which it was soon afterwards [their] unhappy fortune to encounter.” [6] [7] Barbadians didn’t have time to be terrified before the Great Hurricane, its sustained winds likely topping 200 miles per hour, flattened their island; no structure remained standing, and impregnable stone fortress walls many feet in width were swept clean away, along with the cannons that manned them. Mature trees were “torn up by the roots entire” and subsequently thrown twenty to fifty feet “from the hole[s] in which [they] grew.” [7] [8] One Mr. Beckford, who had been a modestly successful sugar planter, described the frenzy inside his house as shingles, then roof flew away, and finally walls collapsed around his family. The “situation of the unhappy negroes who poured in upon [the group] as their houses were destroyed, whose terrors seemed to have deprived them of sense and motion, not only . . . augmented the confusion of the time, but very considerably added, by their whispers and distress, to the scene of general suspense and fluctuations of hope and alarm.” [8] [9]

An estimated 4,500 people died in a matter of hours. And the hurricane wasn’t finished. 6,000 people from St. Lucia and 9,000 people from Martinique joined them. Whole European fleets shipwrecked and then sank to the bottom of the sea. All told, the storm claimed over 27,500 lives. Given the extreme ferocity of this storm, it’s a wonder anyone in its path lived through the event. British naval captain John Hawkins recalled the whirlwind as having a “violence exceeding description: its roar was deafening: nature seemed to exhaust her whole force, had not every succeeding blast proved the contrary.” An “intense darkness, except when relieved by repeated flashes of lightning, the shattered sails flapping in the wind . . . occasioned panic” among even the most experienced sailors. Their sister ship Cameleon “disappeared [from their] view . . . and was never heard of afterwards.” Only through “Providence” were Hawkins and his crew saved from the same “melancholy fate.” [9] [11]

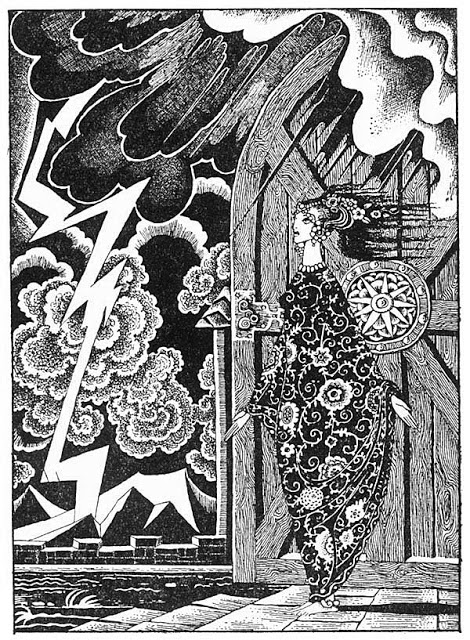

In the Western imagination, storms too, have been engines of transport and change — not simply foilers of travel and killers of sailors, but catalysts. As the clouds bubbled and boiled in the sky, plunging the world beneath them into darkness, the “wind began to switch,” and storm victims felt their brittle structures start to “pitch.” The overwhelming noise and terror often separated them from others caught up in the maelstrom as each of them prayed for his own deliverance. You gods of mysterious designs, “You lift[ed] me up to the wind and cause[d] me to ride . . . You dissolve[d] me in a storm.” [10] [12] And unlike the Barbadian planter left behind with the wreck of his house and a horde of hysterical negroes, a select few were able to “ride the winds” over the clouds and beyond the rainbow.

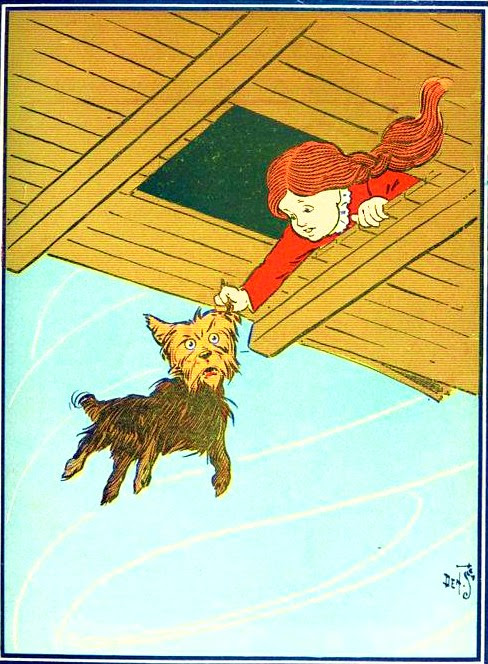

Dorothy stood near the door of her one-room house and stared out across the Kansas fields. Like that of a vast “gray” ocean stretching from horizon to horizon, so too the “great gray prairie . . . reached to the edge of the sky in all directions. Not “a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country on every side.” But today, the sky was “grayer than usual,” and her Uncle Henry looked more solemn than he normally did (he never laughed). [11] [13] Squinting into the distance, he “heard a low wail of the wind” approaching from the north. They both “could see where the long grass bowed in waves before the coming storm.” But suddenly, “there now came a sharp whistling in the air from the south,” and as “they turned their eyes that way they saw ripples in the grass coming from that direction also.” [12] [14] A twister! And they were caught dead center!

Uncle Henry ran to secure the horses, and Aunt Em yelled at Dorothy to follow her through the trapdoor and into the small cellar; but Dorothy was more worried about her dog Toto, who had taken refuge under her bed. As she scooped the little terrier up and made for the basement, “a strange thing happened.” The house began to shake on its hinges, and it “whirled around two or three times and rose slowly through the air. Dorothy felt as if she were going up in a balloon . . . until it was at the very top of the cyclone; and there it remained and was carried miles and miles away as easily as you could carry a feather.” At first, she feared that they would be “dashed to pieces” once the house fell back to earth, “but hours passed and nothing terrible happened.” [13] [15] Even though the storm continued to wail and squall around them, the girl and her dog fell asleep on her bed — it had been a great shock, after all, and she felt worn out. And when she awoke some time later with a sharp thump! Dorothy realized that the “cyclone had set the house down very gently — for a cyclone,” anyway. [14] [16] She and Toto had weathered the storm and survived the shipwreck.

L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) was perhaps the greatest American children’s book ever written, and its greatness was partly due to its adherence to the classic shipwreck narrative — an archetypal story as old as the Western experience itself. In this narrative, the hero, who often longed for adventure, found himself far from home and marooned by a storm that miraculously spared him. The spin of a cyclone at first mesmerized, then terrified, next lulled into a kind of hypnotic submission, and finally delivered the hero onto strange shores (we all have an unconscious desire to be “caught” by such fantastic whirlwinds, to see their insides, to dive into the eye of a storm). The Odyssey, of course, was the best-known ancestor of this genre, but many modern science fiction and fantasy tales have really been stories about sea voyages and shipwrecks, too. Outer space became the ocean, featureless, dark and deep, with only stars to guide the way; time travelers clutched the sides of their machines as they lurched through wormhole-whirlpools until finally crashing onto alien worlds.

This fearsome and communal activity — the sea voyage — became an intensely individual and personal experience during a storm or shipwreck. Dorothy’s aunt and uncle remained in Kansas during the little girl’s flight toward Oz; only Toto accompanied her. Conspiracies of god-driven storms and bouts with deadly monsters eventually deprived Odysseus of his loyal shipmates. Prospero of William Shakespeare’s Tempest manufactured a hurricane that separated Antonio and Alfonso, the King of Naples, from his son Ferdinand. The young man “quit the vessel,” crying out that “Hell is empty, And all the devils are here!” [15] [18] The three men washed up onto nearby beaches convinced that the others had drowned in the tumult.

The hard-bitten sailors in Joseph Conrad’s Pacific-set “Typhoon” ceased their card games when the caterwauling winds seemed to “explode all round [their] ship with . . . a rush of great waters . . . In an instant the men lost touch of each other.” This was the disintegrating power of a great wind: “it isolate[d] one from one’s kind. An earthquake, a landslip, an avalanche, have overtaken a man incidentally — without passion. A furious gale attack[ed] him like a personal enemy, trying to grasp his limbs, fastening upon his mind, [and] seeking to rout his very spirit out of him.” [16] [19] Jukes, the first mate, “was driven away from his commander,” and he thought himself tossed “a great distance through the air. Everything disappeared — even, for a moment, his power of thinking.” Much like Dorothy’s drowsy surrender to the tornado, after battling the typhoon for some time, Jukes became indifferent — had succumbed to a “forced-on numbness of spirit.” The “spell of the storm had fallen upon” him, and a bone-deep fatigue made further effort seem impossible. [17] [20]

And it was at that moment of capitulation to the elements — for sleep or for death — that the storm delivered each of their human (and canine) cargoes to a place unmarked on any map.

2. Color and Danger

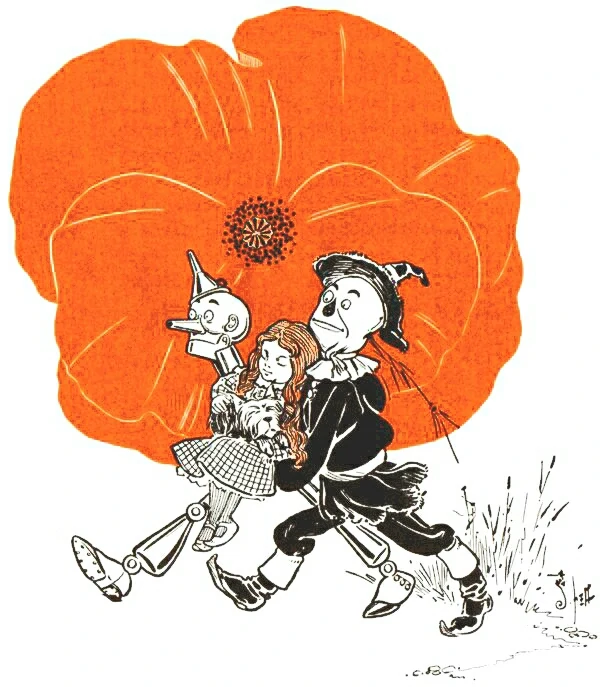

Color is an often overlooked (so to speak), but crucial symbol in life and literature. Because we are creatures of the day (yes, even you “night owls”), children of the sun, we thirst for it almost as much as we do our colorless water. Vivid color signifies both beauty and danger; a poison dart frog or coral snake might be eye-catching, but beware. Perhaps think twice before eating those bright, cheerful-looking berries. A detour around the red poppy field would be wise. And so it is with shipwreck stories. When the storm’s victims woke from their trauma, they blinked in wonder at the colorful and strange new worlds where they found themselves stranded — only to intuit something “off” in the allure — the proverbial “too good to be true” about the place and about the racially dissimilar natives who greeted them.

Indeed, surviving the initial storm and wreck was no guarantee that travelers would reach home or safety; their problems had only begun. In the sixteenth century, Portugal was the preeminent European naval empire, and its galleons frequently made “the India Run”: a trade route from the Far East, down the coast of East Africa, round the southern Cape, and north again to Lisbon. The proud Portuguese armada — the ships that were icons of European expansionism and the continent’s growing global muscle — became symbols of shattered European pride when wrecked. The public became obsessed with shipwreck narratives during the four centuries of uninterrupted white imperialism, and few were more harrowing than the account of the 1552 tragedy of the Great Galleon São João. The ship set sail from Cochin, India, but soon violent storms prevented Captain Manuel de Sousa Sepúlveda from rounding the Cape; the São João splintered in two, and the passengers abandoned the lost ship and washed up onto the beaches of Natal (those who did not drown, that is). Surviving the storm was the easy part.

De Sousa, who was also traveling with his wife and two small children, marveled with the others at the natural beauty of southern Africa — a place not unlike the Mediterranean coasts of which he was familiar. But this was no friendly European sea, nor was it a god-fearing land. Dangerous “kaffirs” watched the party’s movement from behind the tree-line, and food was growing scarce. For over one hundred days, the dwindling group walked north in search of salvation, all of them slowly succumbing to injury, hunger, and madness. Near the end of his journey, de Sousa buried the younger of his children “with his own hands,” while his weeping wife — who had little left of her dress to hide her nakedness — buried with sand the lower half of her body in shame. Though “out of his wits” and limping from a leg wound inflicted by hostile kaffirs, de Sousa went in search of food for his remaining family members. When he returned, he found his wife and second child also dead. The overcome man sent his slaves away and “did nothing but sit beside her with his face in his hands for about half an hour without weeping or saying anything . . . then he rose and began to dig [another] grave in the sand, [still] without saying a word . . . once this was done he turned and followed the path he had taken when searching for fruit . . . into the jungle, never to be seen again.” [18] [21] What the sea did not accomplish, Africa did. Let this be a lesson to all: though it possesses natural beauty and rich resources, Africa is nothing but a black cannibal of white meat.

The Narrative of São João became a sensation throughout Europe, prompting other adventurers to publish their own epics about danger on the high seas and death by violent natives. “True shipwreck” was the sixteenth and seventeenth-century equivalent of our modern “true crime” genre in terms of fascination and popularity. So, it was very likely that Shakespeare would have heard of São João’s fate, or of tales similar in nature — hence the Bard’s recurring shipwreck plot, The Tempest perhaps the most famous example of these.

Years ago Prospero inherited the title of Duke of Milan, but his wicked younger brother Antonio coveted the estate for himself and arranged for Prospero and his daughter Miranda to be marooned on a deserted island. Consumed with spite, Prospero devoted himself to sorcery so that one day he might have his revenge. Sure enough, fate brought near to the island a ship ferrying Antonio as well as the King of Naples and the king’s son Ferdinand. Prospero seized his chance and summoned a “tempest” that shipwrecked these noble passengers.

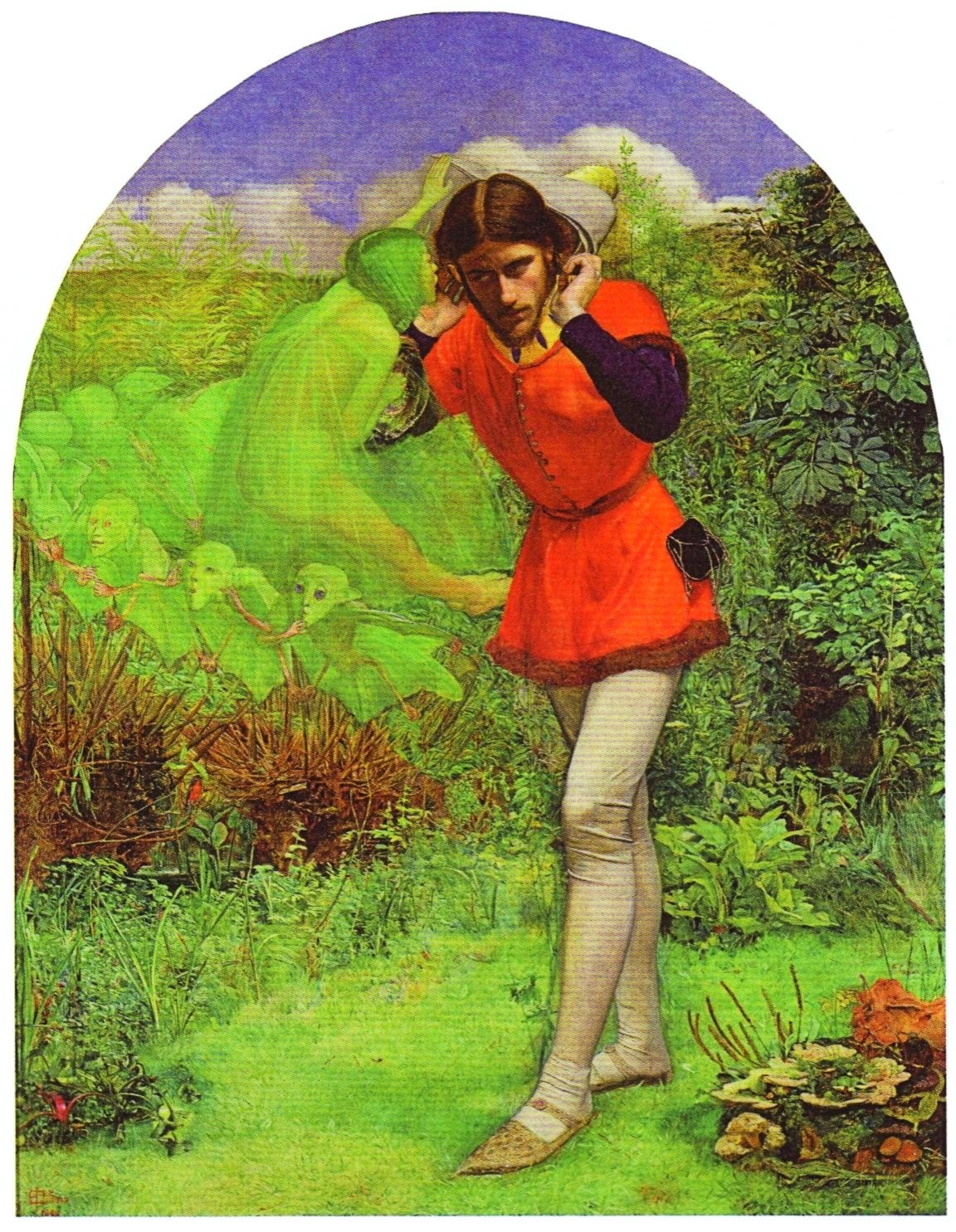

When Prince Ferdinand regained his wits on the “yellow sands” of Prospero’s island, his wonder at its beauty equaled his despair over his father’s presumed death. Ariel the woodsprite sang in the prince’s ear, “allaying both [Ferdinand’s] fury and his passion with [a] sweet air.” [19] [22] The fairy bade the young man to follow the enchanted music to its source. The prince’s father and Antonio meanwhile, had washed up some distance away, and both echoed the sentiment and wondered that “the air breath[ed] on [them] here most sweetly.” Their garments, which should have been ruined by salt water and caked with mud, were instead all “freshness and gloss, being rather new-dyed than stained.” Glancing round, Antonio noticed too, that “Here is everything advantageous to life . . How lush and lusty the grass looks! How green!” Still, the duke was uneasy, for the “sweet air” had almost a sickly taint, like a splattered peach spoiling in the sun: “rotten . . . as ‘twere perfumed by a fen.” [20] [23] Indeed, Prospero’s bitterness had festered for years and infected the entire island. Antonio and the king were right to feel afraid, for the old sorcerer aimed his wrath directly at themselves. One of his weapons was a deformed creature called Caliban — a name unnervingly similar to “cannibal.”

The great satirical classic Gulliver’s Travels (a parody of the more earnest Robinson Crusoe) also began with a storm and shipwreck, which spared only the protagonist Lemuel Gulliver. And after waking seemingly alone on a “deserted” island, Gulliver looked about him and decided that never had he “beheld a more entertaining prospect. The country around appeared like a continued garden, and the enclosed fields, which were generally forty feet square, resembled so many beds of flowers. These fields were intermingled with woods . . . and the tallest trees . . . appeared to be seven feet high. [He] viewed the town on [his] left hand, which looked like the painted scene of a city in a theatre.” [21] [25] A picturesque, perfect little world in miniature. Unfortunately, Gulliver also found himself tied down with rope and the prisoner of a tiny race of people called the Lilliputians, whose concerns were similarly small and petty. The Lilliputian emperor had no intention of releasing Gulliver. Instead, he planned to use his new giant as a weapon with which to enslave his rivals, the Blefuscudians (whose crime was a heretical preference for cracking the rounded end of an egg). Gulliver thus found himself at the mercy of malicious political intriguers and an unforgiving monarch.

Dorothy of Kansas had somewhat better luck and rose from her bed to “bright sunshine” slanting through the windows and “in the midst of a country of marvelous beauty. There were lovely patches of greensward all about, with stately trees bearing rich and luscious fruits. Banks of gorgeous flowers were on every hand, and birds with rare and brilliant plumage sang and fluttered in the trees and bushes. A little way off was a small brook, rushing and sparkling along between green banks.” [22] [26] For a little girl used to nothing but flat gray prairies, this new Munchkinland was delightful, if a bit overwhelming. The farms in Oz were nothing like those in Kansas. The fences were neat and painted in fresh shades of blue, and beyond them grew wheat in abundance. Unlike the farmers Dorothy knew from home, the people of Oz seemed able to “raise large crops” with no trouble at all. But she quickly learned that Oz was “a country that [was] sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible.” [23] [27]

According to some interpretations, Baum’s book was an allegory about turn-of-the-century populist/agrarian politics and bimetallism. The Great Plains, South, and areas of the Western United States suffered punishing droughts, dust bowls, and depressions long before those afflictions were granted capital letters in the 1930s, and Baum himself was very familiar with these struggling farm communities. In keeping with the supposed bimetal motif, Dorothy’s slippers in the book were silver as she traipsed along the “road of yellow brick” toward the “City of Emeralds.” But the makers of the 1938 film version wanted to impress audiences with their new technicolor innovation. And what better color with which to show off Oz’s gorgeous cinematography than slippers of ruby red (and the film is beautiful, readers; time has not dulled the loveliness of Wizard of Oz; and I’ve yet to come across a film with more iconic lines and scenes than The Wizard of Oz. It is no exaggeration to say that if one wants to understand America and its cultural references, one must watch Oz)? In past centuries, “color” was nearly synonymous with red — it was The Color. And we’re hardwired to pay it great attention, because it is the color of blood and fire. A “lady in red” is almost always a femme fatale — a red flag of warning to you, gentlemen. And when you see this standard raised, expect no quarter, for red is not a merciful shade. In this case, the Wicked Witch of the West did not intend to spare Dorothy for “stealing” the Witch of the East’s ruby slippers.

The Time Traveller in H. G. Wells’ novella must have felt very much like Dorothy after emerging from the “continuous grayness” of his rocky journey through the centuries. His machine passed through a storm, and he noticed that “the sky took on a wonderful deepness of blue, a splendid luminous color like that of early twilight; the jerking sun became a streak of fire, a brilliant arch . . .” He saw great and splendid architecture “rising about [him], more massive than any buildings of [his] own time, and yet, as it seemed, built of glimmer and mist. [He] saw a richer green flow up the hill-side, and remain there, without any wintry intermission. Even through the veil of [his] confusion the earth seemed very fair.” Everything shone with the wet of the thunderstorm, and the white of unmelted hailstones peppered the ground at his feet. The Time Traveller “felt naked in a strange world.” [24] [29]

And just as Dorothy met the curious race of small Munchkin people in the land of Oz, the Time Traveller met the slight Eloi people immediately after his arrival. They were “beautiful and graceful creatur[es], but indescribably frail.” Their piqued and “flushed face[s] reminded [him] of the more beautiful kind of consumptive — that hectic beauty of which [he] used to hear so much.” An eerie, “Dresden china type of prettiness.” Their minds proved just as childlike as their looks when one of the Eloi asked the Time Traveller if he’d come from the sky in a thunderstorm (though this was closer to the truth than their seven-year-old intellects realized). With great cheer, they brought their visitor “a chain of wildflowers . . . until [he] was almost smothered with blossom.” [25] [30]

But it soon became clear that evolution had played a nasty trick on mankind, for the great towers that past civilizations had built were now “dilapidated.” The stained glass of the windows were smashed in many places, and everything inside them weighted with dust. “Nevertheless,” the Time Traveller admitted, “the general effect was extremely rich and picturesque” . . . at least during the day time. Amidst the riot of bloom and “hectic” color, the Traveller sensed an unspoken dread. Something had gone terribly wrong in this Eden of no paradise. Broken windows and bad housekeeping were the least of anyone’s problems. [26] [31]

3. Lost and Found

“I cannot understand,” the Scarecrow began, “why you should wish to leave this beautiful country and go back to the dry, gray place you call Kansas.” But to Dorothy the answer was simple: “No matter how dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there than in any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place like home.” The Scarecrow shrugged sadly. “Of course I cannot understand it,” he said. “If your heads were stuffed with straw, like mine, you would probably all live in the beautiful places, and then Kansas would have no people at all. It is fortunate for Kansas that you have brains.” [27] [32] The Scarecrow’s ironic musing aside, intellect has had very little to do with the connection we’ve had to the people and places that belonged to us — that we recognized intimately. Many storm and shipwreck survivors returned home wiser and grateful. Magic tempests and storm-tossed seas separated the victims from those they loved, but the voyage eventually came full circle and back again to the sacred communion with homeland. Odysseus returned to Ithaca and recovered his throne; Prospero forgave his enemies and regained his social position as Duke of Milan, and his daughter married Prince Ferdinand. “Oh, Aunt Em! I’m so glad to be at home again!” [28] [33]

Yes, some shipwreck survivors learned just enough of other places to make them more appreciative of home and family. But not always. Others learned too much and became ultimately unable to settle back into their native lands and ordinary lives. Was the colorful fantasy land the dream, or was it a place where, instead, they’d never lived so intensely — where they finally awakened? And when they came back from Nod, did they also go back to sleepwalking again? The reappeared Time Traveller raked his hands through his hair incredulously. The “room and you and the atmosphere of every day is too much for my memory. Did I ever make a time machine?” [29] [34] How do we reconcile the fact that we are born explorers and travelers, yet we do ourselves and our communities/nations best when we remain home and bound to the land of our kin? This, I believe is the ultimate question stories of storm and shipwreck ask of us.

Gulliver suffered a permanent estrangement of this kind after his last mishap at sea and subsequent marooning among the Houyhnhnms — a peaceful race of intelligent horses. He absorbed the Houyhnhnm disdain for mankind and their “uncivilized” behavior, referring to all humans with the Houyhnhnm slur, “yahoos.” During earlier trips, Gulliver could hardly wait to go home and escape the strange worlds of little tyrants and grotesque giants. But now he mourned his departure from his equine masters. His wife and family “received [him] with great surprise and joy . . . but,” he confessed, “the sight of them filled [him] only with hatred, disgust, and contempt.” After a passionate embrace from his wife, Gulliver blacked out for an hour, “having not been used to the touch of that odious [human] animal for so many years.” [30] [35] Neither could he endure his children for the loathsome smell. Almost immediately, he bought several horses with whom he could more easily and comfortably converse (which he did four hours per day in the stables). In the most important ways, Gulliver never returned home, for he’d left his heart in Houyhnhnm land.

And for his part, the Time Traveller barely managed to escape the dystopia of the Eloi and Morlocks and not without personal tragedy. Upon his return, a group of friends — great men of learning and science like the Time Traveller himself — greeted him with astonishment. He was in an “amazing plight. His coat was dusty and dirty, and smeared with green down on the sleeves; his hair disordered, and as it seemed to me greyer . . . his face was ghastly pale . . . as by intense suffering. For a moment he hesitated in the doorway, as if he had been dazzled by the light.” [31] [36] The gathered men found his tale of the future incredible; to the narrator, the Time Traveller swore to bring back photographic proof of his expeditions. He then asked, “if you’ll forgive my leaving you?” The narrator promised to wait for him, but now he was “beginning to fear that he must wait a lifetime.” [32] [37] The Time Traveller had been missing for three years. Though it caused him immense pain, he had become hopelessly tied to the plot of storm and shipwreck — addicted to the tantalizing lure of knowledge that his machine represented. He wanted to lift the veil over and over again, even though he knew that behind it was unbearable ugliness. I have to conclude that humans are not meant to know far into the next millennia, else we be lost; one lifetime is jarring enough. But to confront the shipwreck of our species in the distant future — the destruction of our planet? Such a thing would overwhelm and shock us into madness. Just as we are bound to a certain homeland, so we are bound to a certain time and the particular battles we are obligated in that spot and during those hours to fight; some places we are not meant to go. It is well that much of Kingdom Come is “still” to us as “black and blank” as the sea beneath storm, as grey and formless as a flat country reaching from horizon to sky. [33] [38] As for the winds and where they will blow us, nobody knows.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [40] Leviticus, 26:33, KJV

[2] [41] An exception to this “nevertheless-we-persist” list would be the Hindenburg tragedy of 1937, which did end the zeppelin fad quite decisively — due most likely to the horrifying and widely consumed footage/radio of the conflagration that destroyed it and thirty-five people on board — neither did the dirigibles’ lumbering pace help their cause.

[3] [42] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Scribner, 2003), 223.

[4] [43] See T. S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. [44]

[5] [45] William Shakespeare, Richard III, I.iv, 21–33.

[6] [46] E. Edwards, “A Short Account of the Hurricane,” (London: H. Reynell, 1780), 3.

[7] [47] Ibid, 4.

[8] [48] Beckford, “A Description of the Dreadful Hurricane,” The Weekly Entertainer (London: 1786), 5.

[9] [49] Anon., “An Account of the Loss of His Majesty’s Ship Deal Castle (London: J. Murray, 1786), 10, 13.

[10] [50] Job, 30:22, KJV.

[11] [51] L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (mobilereference), 4.

[12] [52] Ibid, 5.

[13] [53] Ibid., 6-7.

[14] [54] Ibid., 7.

[15] [55] William Shakespeare, The Tempest, I.ii, 397–403.

[16] [56] Joseph Conrad, “The Typhoon [57],” 57.

[17] [58] Ibid., 63.

[18] [59] A Tragic Story of the Sea, João Almeda Flor and John Elliot, eds. (Lisbon: 2008), 103.

[19] [60] The Tempest, I.iii, 67-68.

[20] [61] Ibid., I.iv, 45-47, 56.

[21] [62] Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels [63], 22.

[22] [64] The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, 7.

[23] [65] Ibid., 11.

[24] [66] H. G. Wells, The Time Machine (New York: Broadview, 2001), 80, 82.

[25] [67] Ibid., 82-83.

[26] [68] Ibid., 85.

[27] [69] The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, 17.

[28] [70] Ibid., 96.

[29] [71] The Time Machine, 152.

[30] [72] Gulliver’s Travels, 559-360.

[31] [73] The Time Machine, 70-71.

[32] [74] Ibid, 154.

[33] [75] Ibid., 155.