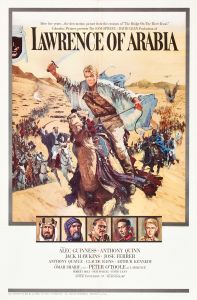

Lawrence of Arabia

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledDavid Lean (1908–1991) directed sixteen movies, fully half of them classics, including three of the greatest films ever made: The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Doctor Zhivago (1965), and, greatest of them all, Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Lawrence of Arabia is repeatedly ranked as one of the finest films of all time, and when one compares it to such overpraised items as Citizen Kane and Casablanca, a strong case can be made for putting it at the very top of the list. I am hesitant to speak of “the greatest” anything, just because I have not seen everything. But when I think of some of my personal favorites — Vertigo, Network [2], Rashomon [3] — I can’t honestly rank any of them higher than Lawrence of Arabia.

Everything about this film is epic: from its nearly four-hour running time and its 70-millimeter widescreen image with astonishing detail and depth of focus — to the magnificent settings in Jordan, Morocco, and Spain — to the music by Maurice Jarre — to the cast of thousands crowned by such stars as Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Omar Sharif, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, José Ferrer, and Claude Rains.

Lean had to go big, simply to do justice to the story. Lawrence of Arabia is about one of the most remarkable men of the last century, Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888–1935) and his role in the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

Based on Lawrence’s sprawling narrative of the revolt, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the script by Robert Bolt (A Man for All Seasons, Doctor Zhivago) and Michael Wilson (The Bridge on the River Kwai) is a supremely masterful screen adaptation. The timeline is simplified, and certain characters are amalgamated, both to save time and heighten dramatic conflicts, but the truth of the story is conveyed.

Like Lawrence’s book, the movie has several layers. First of all, it is a historical narrative. Second, it offers lessons in political philosophy. (The word “wisdom” in the title should have been a warning.) Lawrence was a nationalist, not an imperialist. To fight the Turks, he favored aiding Arab nationalists rather than spending British lives to conquer territory and resources in Mesopotamia. But, against Lawrence’s own intention, Seven Pillars also makes a case for empire, a case that Lean’s film clearly reinforces. Third, there is a strong element of Nietzschean self-mythologization: what Aleister Crowley calls “auto-hagiography” and the Arabs call “blasphemy.”

On the symbolic plane, Lawrence overthrows the three Abrahamic faiths by rejecting their doctrines and reversing or rewriting their central stories with himself as the hero. The movie takes this process further, both reflecting upon the process by which Lawrence became a legend and perfecting it: cinema as apotheosis. I want to focus on the latter two layers. Thus I will skip huge stretches of the story and leave those for you to discover on your own.

T. E. Lawrence was one of five illegitimate sons of an Anglo-Irish Baronet, Sir Thomas Chapman, and an English mother, Sarah Junner. Highly intelligent, Lawrence read history at Jesus College, Oxford from 1907 to 1910. From 1910 to 1914, he was an archaeologist in the Holy Land, working with such eminent figures as Leonard Woolley and Flinders Petrie. Woolley and Lawrence also gathered intelligence for the British in the Negev Desert in early 1914.

When the World War broke out, Lawrence enlisted. Fluent in French and Arabic and knowledgeable of Arab history and culture, he received a military intelligence post in Cairo. In June of 1916, when Sharif Hussein, Emir of Mecca, led an Arab revolt against the Ottomans, Lawrence was sent to Arabia to gather intelligence. The rest is history.

The movie begins with Lawrence’s death in a motorcycle accident in 1935, at the age of 46. After a memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral attended by the crème of the British establishment, a priest asks if Lawrence “really belongs here,” which introduces the theme of Lawrence as an outsider. The first half of the movie can be seen as an affirmative answer to that question.

Then we flash back nearly twenty years to Lawrence in Cairo. From the start, Peter O’Toole plays Lawrence as slightly autistic and ambiguously gay. He also has a masochistic side. He likes to extinguish matches with his fingers. “The trick . . . is not minding if it hurts.” It is a small exercise in self-overcoming, a hint of greater things to come.

Lawrence’s commander, General Murray, despises him as an overeducated misfit, but a civil servant Mr. Dryden (a composite character played by Claude Rains) values his intelligence and language skills. Dryden “borrows” Lawrence for an intelligence gathering mission to Arabia. He is to meet Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness), the son of Sharif Hussein, and evaluate his leadership potential.

Lawrence tells Dryden that he thinks this mission will be “fun.” Dryden says that the only people who find the desert fun are Bedouin and gods. His unstated premise is that Lawrence is neither. Lawrence flatly declares, “No, it will be fun.” If Dryden is right, and Lawrence is not a Bedouin, that implies that Lawrence thinks of himself as a god. To underscore Lawrence’s funny idea of fun, he lights a match. But this time Lawrence blows the flame out.

Crossing the desert to find Faisal, Lawrence’s guide Tafas is killed by Sharif Ali (Omar Sharif) for drinking at his well. You see, Tafas is from the wrong tribe. This prompts a bit of political philosophy delivered with autistic frankness that borders on the suicidal, given that it is spoken to a man holding a smoking gun: “As long as the Arabs fight tribe against tribe, they will be a little people, a silly people, greedy, barbarous, and cruel.” A nation comes into being when tribes of the same people put aside petty differences and rivalries and embrace a common government, including the rule of law, for a higher good. Throughout his adventures in Arabia, Lawrence’s dream of a rising Arab nation is stymied by tribal rivalries and blood feuds.

On autistic principle, Lawrence rejects Ali’s help in finding Faisal, preferring to risk it on his own.

When Lieutenant Lawrence reaches Faisal, he is ordered by his British military advisor, Colonel Brighton, to say nothing, observe, and report back to Dryden. But Lawrence is irrepressible. As an autist, when he has ideas, he can’t keep them to himself, which intrigues Faisal. Brighton counsels a strategic withdrawal to Yenbo, where the British can resupply him. Faisal wants the British fleet to take the port of Aqaba, but Brighton refuses. It is too well-defended. When Brighton leaves, Faisal bids Lawrence to stay. Faisal naturally fears the English have designs on Arabia, but he is forced to depend upon them: “We need the English or — what no man can provide, Mr. Lawrence — we need a miracle.”

This prompts Lawrence to spend a night brooding in the desert. The next morning, Lawrence suggests to Ali that the Arabs should take Aqaba themselves. Aqaba’s guns point toward the sea, because an attack from the land was deemed unlikely. Ali points out that such an attack would require crossing the Nefud Desert, a waste that even the Bedouin avoid. Lawrence proposes crossing the Nefud with fifty men — all members of Ali’s tribe — then raising more troops from the Howeitat tribe on the other side. Ali agrees.

When Lawrence tells Prince Faisal that he is “going to work your miracle,” Faisal replies “Blasphemy is a bad beginning.” Lean films Lawrence’s nocturnal meditations as something more than just a brainstorming session. Now we know that it was a step toward apotheosis.

[4]

[4]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [5]

As Lawrence and his followers make their last push across the Nefud, one of the men, named Gasim, falls off his camel in the dark. When his riderless camel is noticed, Lawrence wants to go back to rescue him. But Ali and the Arabs say they dare not risk it. Gasim’s time has come. “It is written,” meaning that it is the will of God. Lawrence declares “Nothing is written” — meaning that the will of God is nothing in the face of the will of man — then he goes back on his own to search for Gasim. As he departs, Ali rages at Lawrence’s “blasphemous conceit” and says he will not be at Aqaba. Lawrence replies that he will make it to Aqaba: “That is written” — by Lawrence himself.

In the space of a single conversation, Lawrence rejects the written laws handed down by Moses and Muhammad. He overthrows God and lays down his own laws. Blasphemy indeed. But Lawrence’s blasphemy is not punished. It is rewarded. When he rescues Gasim, the Arabs begin to idolize Lawrence. As Lawrence sleeps, Ali burns his uniform.

The next day, they dress him in the white and gold robes of a sharif of their tribe, conferring noble status on him. It is proclaimed, “He for whom nothing is written may write himself a clan.” Because Lawrence is a bastard in England, he cannot inherit his father’s name or title. For Ali, that means he is free to choose his own name. He is free to found his own family, clan, or dynasty. He is free to be somebody’s ancestor, not somebody’s heir. This is the privilege that descends on all men who bring victory in battle. It is how aristocracies everywhere are born. The Arabs call him “Aurens.” Now Ali wishes to style him “El Aurens,” which is the equivalent of the German “von.” Lawrence is beginning to enter — and alter — Arab society.

The night before Lawrence’s men and the Howeitat are to strike Aqaba, a shot rings out. One of the Howeitat lies dead, killed by one of Lawrence’s men. The Howeitat demand justice, but if they execute the killer, his own tribesmen are bound to avenge him. Tit-for-tat violence will destroy the alliance. Arab tribalism is about to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

But Lawrence has a solution. He will execute the prisoner. He will take the blame. He, not the Howeitat, will bear the brunt of the blood feud of the dead man’s tribe. Thus the alliance of the two tribes can be maintained for the attack on Aqaba. Lawrence is offering himself as a scapegoat to prevent tribal conflict from spinning out of control.

Of course, in a sense Lawrence can’t really serve as a scapegoat, because he knows that he is no danger of actually being punished by Gasim’s tribe for executing him. He has already been hailed as a sharif by Gasim’s own kin.

The scapegoat here functions as a symbol of the political enemy in Carl Schmitt’s sense. If the Arab tribes are to become an Arab nation, they must find a way to take the enmity between them and place it on an outsider. If the Arabs are to become a political “us” they must have an external enemy, a political “them” against whom to define themselves. Lawrence wants it to be the Turks, but he knows that a people in need can create an enemy in its own midst, then externalize it. Lawrence is willing to fill that role in a pinch.

Ironically, though, Lawrence’s gesture also undermines nationalism and makes a case for empire. In Xenophon’s The Education of Cyrus, book 3, we learn of how enemy tribes can be unified not by a common enemy but by a common “friend.” Two enemy peoples in the Caucasus, the Armenians and the “Chaldeans,” are locked in perpetual warfare. Neither group is strong enough to defeat the other, so their costly conflict can only be terminated by a third party.

Cyrus occupies and fortifies the highlands between the Armenians and Chaldeans. He pacifies them by offering to ally himself to whichever tribe is wronged by the other. Then he delivers the fruits of peace by brokering mutually enriching economic exchanges between the two tribes in place of mutually impoverishing conflict.

None of this would be possible without a third power, an outsider who is above their conflicts and benevolently disposed toward them. This was the legitimating ideology of the Persian empire; hence Cyrus became known as the “prince of peace.” Lawrence plays the same role in brokering peace between the tribes. It is, of course, but a small step from hero to emperor. Contrary to the principle of national self-determination, sometimes only an outsider will do.

When Lawrence and the rest of us see the face of the condemned man, it is a punch in the gut. It is Gasim, the man Lawrence risked everything to save. Lawrence asks Gasim if he is guilty. “Yes.” Then Lawrence puts six bullets in him. When he flings away his gun in disgust, a mob converges on it, as a holy relic. Lawrence is becoming a legend. (In reality, Lawrence executed a different man. By making Gasim the killer, the screenwriters not only made the story more economical, they also increased its dramatic power.)

After Aqaba is taken, Lawrence basks in victory for a few moments by the seaside, where Ali throws him a garland of flowers, stating “The miracle is accomplished. . . . Tribute for the prince, flowers for the man.” Lawrence replies “I’m none of those things, Ali.” When asked what he is then, Lawrence says, “Don’t know.” But he’s being coy. If he has worked a miracle, he’s a god, or on his way to becoming one.

When the telegraph equipment in Aqaba is smashed by the excitable Arabs, Lawrence proposes taking the news to Cairo by crossing the Sinai desert. “Why not? Moses did it.” To which Auda abu Tayi, the leader of the Howeitat (Anthony Quinn in his most compelling role) replies, “Moses was a prophet and beloved of God.” But Lawrence is doing more than imitating Moses. He’s already tossed away the written laws of Moses and Muhammad. Now he’s reversing Moses’ journey by going back into Egypt.

When Lawrence arrives in Cairo, he’s dressed in Bedouin robes and caked with filth. But Lawrence walks into military HQ like he belongs there. He was an outsider even when he wore the uniform, but now it’s obvious. Naturally, he is not welcomed until he is recognized as one of their own. He looks like a beggar. He has gone through hell. But when he reports that he has taken Aqaba, everyone from the top brass to the lowest guardsman knows a good thing when he sees it.

General Murry has been replaced by General Allenby, a far shrewder leader superbly played by Jack Hawkins. Allenby promotes Lawrence to major on the spot. Brighton declares it a “brilliant bit of soldiering” and recommends Lawrence be put up for a commendation. Dryden says, “Before he did it, sir, I would say it couldn’t be done.” When Allenby summons the lowly Mr. Perkins into his office and asks his opinion of Aqaba, he says “Bloody marvelous, sir.” We know Perkins is a lowly fellow because we only see his boots, stamping to attention as he enters and leaves.

Allenby proposes a drink at the officers’ bar. The beautifully filmed and choreographed sequence is one of the movie’s most memorable. The British HQ was filmed in a magnificent palace in Spain. The music is a splendid march. Allenby, Lawrence, and company sweep through the halls and down the grand staircase — past rank after rank of smartly uniformed officers and sentries, standing at attention and saluting — into the sumptuous bar, where all the officers spring to attention until Allenby put them at ease and begs their permission to drink there, as a guest of Major Lawrence. It is a perfect image of how hierarchy is oiled by magnanimity, manners, and good humor. We pretty much know where David Lean stands on the empire vs. nationalism question. The British Empire has seldom seemed better oiled and more glamorous on screen.

But it is precisely the British ability to look past appearances and to recognize the talents and achievements of an outsider and misfit like Lawrence that made this victory possible. As Allenby and Lawrence continue their conversation in the courtyard, the camera follows Lawrence’s eyes to the galleries above, which are lined with onlookers. Again, we see a legend forming. When Allenby takes his leave and Lawrence returns alone to the bar, the officers briefly stand silent then burst out in acclaim. When the priest at Saint Paul’s asks, “Does he really belong here?” he means at the very center of one of the world’s great empires. Here we see that the answer is yes. It is an enormously moving climax, and we’re only at the Intermission.

In the first half of the movie, Lawrence makes himself a legend in service of Arab nationalism. In the second half, he meets a rival myth-maker, Jackson Bentley, a fictional American journalist based on Lowell Thomas and played by Arthur Kennedy. Bentley’s goal is to use the Arab anti-colonial revolt and the romantic figure of Lawrence to build American sympathy for the war. Prince Faisal replies: “You are looking for a figure who will draw your country toward war. Aurens is your man.” Amusingly, Bentley tells Faisal, “I just want to tell your story.” The bastards still say the same thing today.

When Lawrence and the Arabs attack a Turkish train, we see apotheosis in action. A victorious Lawrence stands on top of the train to receive the acclaim of the tribes. A wounded Turk shoots him. Lawrence falls to the sand, where he takes stock of his wound. When a bloodied Lawrence returns to the roof, the tribes are ecstatic. Lawrence prances on the roof of the train like a model on a catwalk, whirling in his robes, drinking up the adulation of his followers.

Looking down through the camera’s eyes, we see only Lawrence’s shadow across the sands and the cheering crowd. Looking up, we see only his silhouette against the sky. Bentley eagerly snaps pictures, which the Arabs correctly believe will steal their virtue. Bentley is stealing — and selling, and exploiting — Lawrence’s virtue, his power.

The juxtaposition of the three-dimensional Lawrence and his two-dimensional shadow and silhouette, along with the journalist’s camera, is a subtle commentary on myth-making. Lawrence is becoming one of the shadows projected on the walls of the cave of public opinion.

In my review of John Ford’s The Searchers [6], I comment on Ford’s framing effect of moving from silhouette to three-D and back to suggest that the domestic world is less real and more fragile than nature, again an analogue to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Lean uses the same contrasts to similar effect. Lean carefully studied The Searchers before filming Lawrence to understand how Ford shot his spectacular Monument Valley settings. He may have taken other inspiration as well.

Sated with loot and desiring to take the winter off, Lawrence’s Bedouin allies melt away. But the British campaign rolls on. Lawrence has been asked to besiege Deraa, but he only has fifty men left, the original number he set out with toward Aqaba. Having worked a miracle once before, he presses on. “Who will walk on water with me?” he asks. More blasphemy. But not even Lawrence can motivate fifty men to take a town garrisoned by thousands of Turks.

So Lawrence proposes to go into Deraa alone. Of course with his fair complexion, golden hair, and blue eyes, he’s going to have a hard time passing, but for some reason Lawrence wants to draw attention to himself — even though he is the most wanted man in the Empire, with a bounty of twenty-thousand pounds. The whole mission makes no sense, and some suspect that it is wholly fictional. Only Ali accompanies him.

Lawrence is arrested, beaten, and most probably raped by a sadistic Turkish general, then thrown into the street. Lawrence’s feeling of invincibility is shattered. He wants to return home and bury himself in an ordinary life. “I’m only a man.” Ali is incredulous, objecting “A man can do whatever he wants!” Lawrence retorts, “But he can’t want what he wants.” Meaning that we may be able to reshape the world according to our desires, but we can’t reshape our desires. Then he pinches his white flesh and says, “This is the stuff that decides what he wants.” Is he referring to his race, which made it impossible for him to pass as an Arab? Is he referring to his sexuality? (Lawrence was most definitely a masochist and probably homosexual.) Whatever his meaning, Lawrence is doubting his outsider magic.

Lawrence meets with Allenby in Jerusalem and asks to be relieved. “I’m an ordinary man, and I want an ordinary job. . . . I just want my ration of common humanity.” Allenby has seen these mood swings before and handles Lawrence shrewdly. “You’re the most extraordinary man I’ve ever met.” Lawrence agrees rather too readily. “Not many people have a destiny, Lawrence. It is a terrible thing for a man to funk it if he has.”

This is Lawrence’s Garden of Gethsemane moment, when he seeks to renounce or flee his superhuman destiny. But that proves impossible. It is not long before the old Lawrence is back. He is going to deliver Damascus to the Arabs. The scene ends dramatically with Lawrence standing in front of a painting of Phaeton falling headlong from the solar chariot declaring emphatically that the Arab tribes “will come for me.”

[7]

[7]You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here [8]

Of course, at Deraa he’s learned the limits of his charisma. So he demands a great deal of money from Allenby as well, to buy allegiance. When Lawrence sets out for Damascus, he has a paid bodyguard of notorious cutthroats, all of them wanted men.

Lawrence’s goal is to beat Allenby to Damascus and install an Arab National Council. He almost loses the race when he comes across an Arab village sickeningly massacred by the retreating Turks. The cutthroats urge “no prisoners.” Ali reminds Lawrence of Damascus. When one of Lawrence’s men charges the Turks and is gunned down, Lawrence unleashes a massacre. This is his Phaeton-like fall. Faisal prophesied it earlier in the film when he said that for Lawrence, mercy is a passion. For Faisal, it is merely good policy. “You may judge which is more reliable.” Clearly, Faisal’s motive was more reliable in the end.

Despite the massacre, Lawrence beats Allenby to Damascus, occupies key facilities, and declares an Arab National Council in charge. Allenby’s response is shrewd. He orders the British army to quarters, including the medical and technical staff. He’s going to let the Arabs muck things up, out of tribal pettiness and general backwardness. Eventually, they will get tired of playing at government and leave. Which is pretty much what happens. “Marvelous looking beggars, aren’t they?” Allenby remarks as he sees the Bedouin begin to slip back to the desert.

The movie ends with Lawrence, now a full colonel, being sent home so the politicians can take over. Along the road, he passes a troop of Bedouins leaving Damascus and more British coming in. It looks anticlimactic, but that’s history.

It also looks like a defeat, but it wasn’t entirely. Prince Faisal held on. He was willing to accept British engineers to run things, but he insisted on flying an Arab flag and declaring himself king. Faisal was eventually run out of Damascus by the French, but he became king of Iraq, which was pretty much a British oilfield with an Arab flag until his grandson was machine-gunned by revolutionaries. His brother became king of Jordan, where his descendants rule to this day. It wasn’t what Lawrence wanted, but without his efforts, the Arabs would have had to settle for a lot less. Lawrence’s sense of mission wavered from time to time, but he didn’t fail the Arabs. Ultimately, they failed themselves.

Visually, Lawrence of Arabia is one of the most beautiful films in the history of cinema. It has been studied obsessively by other filmmakers but never equaled. Every new viewing discloses new influences. (For instance, surely Faisal’s silent, red-robed guardians gave George Lucas an idea or two.) If a picture is worth a thousand words, Lawrence of Arabia is worth a million. Better, then, that you see it for yourself.

What did Lawrence do after Arabia? There were stints at the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office. But having made history, he found office work boring. So he turned his talents to making legend, writing Seven Pillars of Wisdom and delivering lectures to enormous audiences. He also filled his ration of common humanity by joining the Royal Air Force. Apparently he found it relaxing to take orders from fools. When his enlistment was up, Lawrence left the RAF in March of 1935. He had his fatal accident before he could begin the next chapter in his legend.

We can only imagine what Lawrence would have thought of Lean’s film. I think it is insightful, but it isn’t necessarily pleasant to be spiritually X-rayed. However, if Lean is right about Lawrence’s ambitions, I think he would have been pleased to see his apotheosis finally made complete.

The Unz Review [9], June 1, 2021

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: