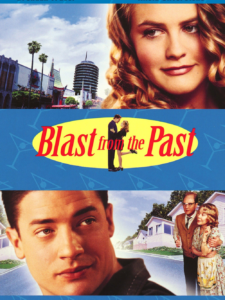

Blast from the Past

Posted By Lawrence Lightfoot On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOn a Sunday last May, while Minneapolis burned, my Yankee sweetheart and I indulged in a double helping of nostalgia. The engine that propelled us along this journey down memory lane was Blast from the Past, an American romantic comedy, now a little more than twenty years old, that celebrated the morals, manners, and milieux of an even earlier time and place, the America sacrificed on the altar of equality of opportunity in the annus mirabilis of 1965.

The plot is simple enough. In the midst of the Cuban missile crisis, a scientist and his wife take refuge in their capacious fallout shelter. A few minutes later, a malfunctioning Sabre jet crashes into their house, creating an explosion large enough to convince them that an atomic armageddon had taken place above their heads. The couple therefore remains underground for 35 years, during which time they raise a son, with the appropriately hopeful name of Adam. Soon after attaining full manhood, Adam ascends to the world above, with the twin mission of acquiring supplies for his parents and a wife for himself.

As anyone familiar with romcoms of the 1990s might easily predict, Adam finds, woos, and, in the end, wins, his Eve. What is somewhat surprising, however, is the degree to which Adam’s success in Cupid’s quest is depicted as a function of the old-fashioned virtues, skills, and attitudes he learned in the time capsule in which he grew up. He triumphs because he is an old-fashioned gentleman, the sort of fellow who, depending on the needs of the moment, can either deliver a condign thrashing to a cad who stepped out of line or stun a pair of jaded Jezebels with his prowess on the dance floor.

In addition to serving as a paean to retro-culture, Blast from the Past handles ethnicity in a way that most readers of this journal would find congenial. With two exceptions, all of the indispensable secondary characters in any romantic comedy — the boorish ex-boyfriend of the heroine, her supportive best friend, and the aforementioned Jezebels — exude the generic whiteness of the California of the middle years of the twentieth century. Indeed, if I were to give in to the temptation to read too deeply into the film, I might even say that they are as much a “blast from the past” as Adam himself.

[2]

[2]You can buy Greg Johnson’s It’s Okay to Be White here. [3]

Adam, the son of Calvin and Helen Webber, gives no indication of being anything other than an Old Stock American. (“Webber” was a reasonably common surname in old New England. “Calvin” speaks for itself.) Eve bears the unmistakably Slavic surname of “Rustikov,” but makes no mention of babushkas, balalaikas, or borscht. She is thus the avatar of the “Heinz 57” people of European ancestry who, in the course of the century that ended in 1965, fully (if slowly) embraced the values and customs of the folks who founded the United States. (At the very end of the film, Adam reveals that Eve’s grandparents had immigrated from Ukraine.)

The only unalloyed villain in Blast from the Past is Jerry, the proprietor of the collectibles shop where Eve is working at the start of the film. Portrayed by a retired professional hockey player, Jerry is far too muscular to fill the shoes of a stereotypical storefront Shylock. Nonetheless, Jerry’s attempt to cheat Adam out out of his extraordinarily valuable baseball card collection, his mockery of the Biblical echo of the Christian names of the protagonists, and the sarcastic benediction of “mazel-fucking-tov,” deprive the viewer of any and all doubt on the matter of his tribal affiliation. (The only other unmistakably Jewish character in the film is an old man who, after observing a bizarre conversation between Adam and an obvious schizophrenic, exclaims, “Can’t you see he’s meshugina!”) [1] [4]

The one black character with a substantial speaking part is Dr. Nina Aron, a well-groomed, well-spoken, well-meaning social worker who, in response to a call from Eve, attempts to take Adam into custody. Movie mavens who like to read deeply into the casting of minor characters may uncover a tale about a black woman who sacrificed her authentic negritude for the sake of a place on the middle rungs of the civil service. (Champions of this theory will, no doubt, point to the obvious homage to baseball legend Henry Aaron in Dr. Aron’s name.) In all likelihood, however, Dr. Aron, who is described in the script as “a kind-looking professional woman,” need not have been black at all.

The remaining BIPOC characters in Blast from the Past — a Pakistani purveyor of pornography, mestizo motorcycle enthusiasts, and a particularly repulsive streetwalker — serve chiefly to underscore the seediness of the Los Angeles neighborhood that had been built over the bunker where Adam had been born and raised. They thus reinforce the message sent by the time-lapse sequence that chronicles the changes experienced by that particular corner of the City of Angels between the early 1960s and late 1990s.

Sadly, the performances of the two most celebrated actors in the film, Christopher Walken and Sissy Spacek, undermine what would otherwise have been a splendid celebration of both cultural conservatism and the white-California-that-was. Mr. Walken, who plays Adam’s father, portrays the anti-communism of the Kennedy years as a tin-foil-hat conspiracy theory, more Alex Jones than Whitaker Chambers. Miss Spacek, in the role of Adam’s mother, presents us with the caricature, beloved of second-wave feminists, of a stay-at-home mom who consumed far too many cocktails in order to compensate for the absence of “fulfillment.”

That said, Blast from the Past is a fine film for a rainy afternoon. For those already in possession of a solid base of sub-special self-respect, it is a pleasant fantasy. For men in the process of serving up red-pills to potential partners, it provides a great way to spark a conversation about issues of importance to the well-being of white people.

* * *

Don’t forget to sign up [5] for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [6] I would think that that line should either read “he’s a meshugina” or “he’s meshuga.” (The former is a noun that means “mad man,” the latter an adjective that is usually translated as “crazy.”) Who am I, however, to correct the Yiddish of a Hollywood scriptwriter?