Too Smart to Be Happy?

Posted By Jim Goad On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,173 words

As I stroll lackadaisically through life’s pollen-belching daffodil fields, it occurs to me that I’ve never seen a depressed person with Down syndrome. No matter how sad their lives may look to outsiders, down to the last pumpkin-headed man and woman they seem blissfully ignorant of how they may appear to others. They happily embrace life as if they are clutching a fistful of multicolored balloons.

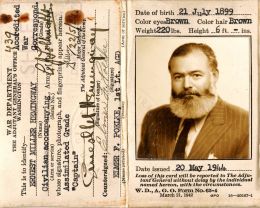

Regarding the opposite end of the cognitive-ability spectrum, Hemingway once said, “Happiness in intelligent people is the rarest thing I know.” He said this before taking a gun and blowing his brains halfway across Idaho.

It’s a bit of a cliché that the smarter you are, the less happy you are, and there’s some statistical evidence to support this idea. The common explanation is that intelligent people are both blessed and cursed with the ability to shovel through the landfills of bullshit that comprise most human interactions and are able to grasp life’s soul-crushing futility in ways that evade those who happily wallow in the half-inch of subliterate pig slop and comforting nursery-school fairy tales that keep the teeming billions of this planet’s cognitive peasants happy, fat, and snoring loudly. Dumb people are not tormented by the existential questions that plagued the young pre-pube Alvy Singer in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, whose mother trots him before an analyst because he learned that the universe is expanding and everything will ultimately fall apart, so what’s the point?

Before I launch into the next segment of this essay and make claims about my intelligence that are going to sound like porno-star dick-bragging, I should clarify two things: 1) I’m only relating what other people have told me, and; 2) I chose to write for this website after a decade of dealing with a supremely dumb and entitled editor because of all the websites that traffic in this sort of material from these sorts of angles, I judged that the editor, writers, and readership were perched at the top of the intelligence pyramid, all other things being equal.

Two things were drilled into my head for as long as I can remember: that I was bad and I was smart. And often, it seemed to be that people thought I was bad because I was smart. No one seemed to think I was smart because I was bad. It exclusively worked the opposite way.

[2]

[2]You can buy Jim Goad’s Whiteness: The Original Sin here [3].

My older brother tells me that when my parents trotted me before an assembly line of shrinks to diagnose why I was so prone to misbehavior, one of them said that I was extremely intelligent and that this would make it extremely difficult for me to get along in this generally dopey world.

About five years ago, a woman who was working as a freelancer for HUSTLER magazine spent about a month interviewing me and doing background research for a feature on me that the editors initially greenlit and then rejected because they said I was “too controversial.” Although I felt bad that she’d wasted all that time, I took it as a badge of honor that I was considered beyond the pale even for HUSTLER.

But the first line of her feature was “Jim Goad is too smart to ever be happy.”

And for a while, I agreed with her, partially out of a lifelong knack for self-pity which I’ve only recently been able to shed, but also due to an immaturity and lack of experience that made me feel, even in my mid-fucking-fifties, that it was easier to blame my unhappiness on the ability to visually distinguish between a dodecahedron and a rhombicosidodecahedron without blinking than it was to blame the fact that, despite whatever coldly robotic cognitive abilities I may possess, even many infants and house pets surpassed me when it came to that alternate form of intelligence known as wisdom.

My father, who wasn’t exactly the nicest guy, always told me that no matter how smart I was, I lacked common sense. And I remember another consistent diagnosis that was passed down from the sages of psychology to my parents: “Your son is way ahead of the class intellectually and way behind emotionally.”

A 2016 study [4] by evolutionary psychologists Satoshi Kanazawa and Norman Li based on the self-reports of 15,197 respondents aged 18 to 28 found that nearly all people, with one significant exception, were happier the more they interacted with people. The one exception was the small cluster of exceptionally intelligent people:

Analysis of this data revealed that being around dense crowds of people typically leads to unhappiness, while socializing with friends typically leads to happiness — that is, unless the person in question is highly intelligent.

This led one reviewer [5] of the study to proclaim that “Hell might actually be other people — at least if you’re really smart.”

Kanazawa and Li’s study led another reviewer [6] to conclude:

For our ancestors, frequent contact with friends was a necessity that helped them to ensure survival. Being highly intelligent, however, meant that an individual was uniquely able to solve challenges without needing the help of someone else. This diminished the importance of friendships to the. . . . For smart people, being in a group can slow them down. It can be frustrating to be the only person who seems to grasp the “big picture,” when everyone else can’t seem to stop squabbling about the details. . . . So, intelligent people will often prefer to tackle projects solo, not because they dislike companionship, but because they believe they’ll get the project done more efficiently. . . . This suggests that their “loner attitude” can sometimes be an effect of their intelligence, not necessarily a preference.

But none of this really clicked for me until I also came across the phrase “communication range [7],” a term coined by American psychologist Leta Hollingworth, who claimed that people are happiest when interacting with people who are within two standard deviations above or below their IQ. For people with an IQ of 100, they are comfortable consorting with both high-end retardates and low-end geniuses. But the higher your IQ gets, so shrinks the pool of people with whom you can communicate without wanting to swallow razors.

When I ponder the tiny handful of friends I’ve known for decades and have never argued with, suddenly it seems like no coincidence that they are also the ones I consider to be both smarter and wiser than me. It has nothing to do with being intimidated by them; it’s that they’ve never annoyed me. Only dummies annoy me. If I prune the dummies from my life, I’m happy. It’s such a simple concept, I feel like a simpleton for not grasping it earlier.

I’ve spent a lifetime describing myself as “socially retarded,” but I was wrong about that, too. Nearly all of society is retarded, and my mistake was making it my problem rather than realizing it’s theirs.

* * *

Don’t forget to sign up [8] for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.