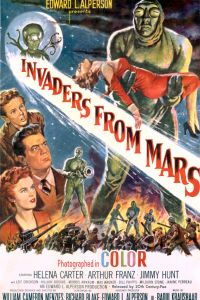

Invaders from Mars

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledInvaders from Mars is a sci-fi film said to encompass all of the paranoia of the 1950s. Director Cameron Menzies realizes this film as the horror of a child trapped in a nightmare. David MacLean (Jimmy Hunt), wakened by horrific thunder, looks outside his window and sees a flying saucer land and submerge itself underground. His father (Leif Erickson), a cheerful scientist, goes out to have a look near the house, and returns stern, blank-faced, and moody. We see David’s fear at the change in his father and, later, his mother.

Night monsters, tunnels, giants, holes where strange voices sing as people are sucked down, and whirling sand set David on edge, as no one listens to him. When his parent’s minds are taken over by Martians, we see David’s world — sets whose odd distortions remind us of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Like him, we look up at adults (a camera angle used in ET). And there’s that path up to the bridge going through barren trees, leading to the sand trap of the Martians, an image repeated over and over from a distance, more dreamlike than real.

Invaders is full of frontal shots and close-ups of faces blank like death masks — certainly recalling the current masking under Covid — where human personality is erased. In the Martian spaceship, David meets the Martian “intelligence”: a creature in a bubble, a silver face framed in a hood with tentacles — an awful, fascinating freak who steals our minds. This bubble is the sinister opposite of the one used by Glinda, the good witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz.

Simple 50s paranoia? No. The terror of a child is timeless. Fear is never passe. Invaders from Mars reminds me of Great Expectations, where young Pip is cowered over by Magwitch, the escaped convict. As George Orwell pointed out in his essay on Dickens, the scenes between Pip and Magwich aren’t real; convicts don’t talk and act that way, but the scene and dialogue capture perfectly a child’s terror.

Certainly, the Martian intelligence was a progenitor of a later face, the supposed face of Mars on the Cydonia Mensae seen by photos taken by Viking I’s voyage on July 1976, a mysterious image of shadows and a headdress, vaguely Egyptian. Whole evenings of Art Bell’s Coast-to-Coast were full of speculation on this face.

The blank faces of David’s parents underscore Invaders from Mars‘ two problems: How can David get his parents back? How can he get anyone to believe him, especially since every authority figure around is now a blank, faceless agent of the Martians?

[2]

[2]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [3]

Help comes from Dr. Pat Blake (Helena Carter), a social worker who befriends David, and Dr. Stuart Kelston (Arthur Franz), a scientist working on a top-secret project with David’s father. In effect, they become surrogate parents to David while he works to get his real parents back. Official society in this film has become frozen and controlled. These three become a team, much like Bart and Zabladowski team up to help Heloise break free of Dr. Terwilliger.

David is in a deadlier situation than Bart is in. He needs heavy artillery, and Kelston and Blake convince Colonel Fielding (Morris Ankrum) that something’s wrong, and the military comes in.

Kelston theorizes the Martians know about a secret rocket the military is developing capable of negating any other country’s defenses. The Martians seem to have figured out that such a weapon could be used against them, and the invasion is less naked aggression than a preemptive strike.

Is this brutal and sneaky? Well, when Israel bombed Iraq’s nuclear power plant in 1981, and repeatedly struck any Iranian attempt at creating what they perceive as a nuclear bomb, is that brutal and sneaky?

For that matter, when Japan snuck attack Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was it not because America had placed a complete embargo on oil and scrap metal, effectively canceling Japan’s war-making potential and wrecking its economy? Oh, that’s right; we don’t teach that. Like the terrorists of 9/11, they hated our democracy.

But back to David. The Martian creatures are kind of silly rather than menacing. With their green bodies, extra-long arms, and clumsy, apelike gait, they could be Seuss monsters. But the caves imply a subconscious fear of creatures, reminding me of the use of caves in Charles Brockden Brown’s novel Edgar Huntley (1799), where a young man seeking justice finds himself caught in underground passages dealing with a mysterious, tall, sleepwalking man who may be a murderer, a panther our hero has to kill and eat in a strange ritual, Indians loose in the cave holding a captive girl. . .

Then that chorus of voices whenever holes in the film open up. It’s not just the soundtrack, because David also hears it — the invasion becomes a sensory experience.

David does win in the end. The military stops the Martians, his parents are saved, but then he and everyone must flee as the Martian flying saucer emerges from the earth in a dirge-like moan like a horrific Moby Dick breaking from the deep. It is a menace everyone has to flee, reminiscent of the imminent threat of atomic annihilation.

David wakes and is reassured by his father that all’s well. After Dad goes back to bed, David looks out the window and sees the flying saucer again seep into the earth; he’s stuck in a recurring nightmare. Paranoia? Or a subliminal menace?

Invaders from Mars is a thinking movie. It’s well-crafted and psychologically strong. Unlike The War of the Worlds (1953), where the Martians just come at us and start a body count, or The Angry Red Planet (1952), with a semi-philosophical semi-wacky plot, Invaders from Mars concentrates on a struggle to save a family. It’s wrong for Martians to steal David’s parents, but they might have had their reasons. The film clocks in at eighty-three minutes, and could have used a few more. I’d like to have known more of the Martians and their motives, and perhaps some interaction between us and them (a sergeant who has been brainwashed and is used for them as a mouthpiece is good, but I wanted more) instead of too much footage of the army getting ready for battle (the stock footage is from WWII, judging by the uniforms and obsolete tanks), but the movie might have become too talky. As it is, the audience is expected to fill in the blanks and use their imagination.

Invaders from Mars is a psychological study of fear, yet is watchable and family-friendly. Fifties movies tended in this direction, which sixties mores soon denigrated. They are films with small budgets, but got a lot of bang for the buck.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: