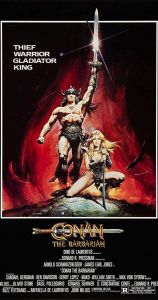

Conan the Barbarian

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOver the years, I caught bits and pieces of John Milius’ 1982 movie Conan the Barbarian — starring Arnold Schwarzenegger as the big lug himself — on cable TV. But I was never tempted to watch the whole film. I finally gave in when I started writing my series on Classics of Right-Wing Cinema [2], and friends urged me to add Conan to my list. I admit that a film about Robert E. Howard’s iconic hero, with visuals borrowed from Frank Frazetta, starring the future California Governator, and directed by Right-wing Jew Milius sounds like a formula for a classic of Right-wing cinema, teeming with paleo-masculine heroics and illiberal political realism. After all, Milius wrote the script for Dirty Harry [3], which is a genuine paleo-masculine, anti-liberal classic of Right-wing cinema.

Sadly, though, Conan the Barbarian is nothing like Dirty Harry, but it is very much like its sequel, Magnum Force [4], also scripted by Milius, in which the character of Harry Callahan is systematically subverted in a decidedly anti-white and politically correct manner.

The Conan movie went through more than a decade of development hell before finally moving forward with Milius at the helm. Oliver Stone had apparently written a four-hour script set in a post-apocalyptic future. Milius discarded Stone’s script entirely, even though Stone and Milius share the final screenwriting credit. Instead of setting Conan in classical antiquity, Milius sets the story in the Dark Ages, borrowing elements from the Norse and the Mongols.

Howard’s Conan is a fearsome warrior, but he is also intelligent, witty, learned, and cunning. He can read and write. He is fluent in a number of languages. He can solve problems and crack codes. These traits set him apart in a world teeming with warriors, enabling him to become a king. In short, Howard’s Conan is no mere barbarian. Milius’ Conan is strong and cunning, but otherwise he is an oaf with very few lines. It is impossible to imagine this man becoming a king, because he really is just a barbarian.

But surely Milius used some of Howard’s 21 Conan stories? No, not really. He borrowed some names and events, but the plot is his invention. This is John Milius’ Conan, not Robert E. Howard’s, which is something of a cheat if you grew up liking Howard’s Conan. Ultimately, though, Milius’ Conan has to be judged on its own merits.

The story opens with Conan as a child. His father is a blacksmith who explains the “riddle of steel” to his young son. Later, Conan’s village is attacked by a marauding band. Actually, they look like a marauding heavy metal band: Spinal Tap, but with real axes. It is a bit much.

The band is led by Thulsa Doom, who is played by James Earl Jones. Jones, of course, was the voice of Darth Vader, so he was an iconic choice for a villain. But Jones is a black man, who is as absurdly out of place in Conan’s world as the llama we glimpse later on in the movie. Thulsa Doom has the power to hypnotize people, which he uses on Conan’s mother, who lowers her sword, allowing Thulsa to lop off her head.

The children of the village are marched off as slaves to toil in a mill, where eventually Conan grows up to be a giant, muscular brute played by Schwarzenegger. Then Conan is sold to another master, who makes a gladiator of him. Howard’s Conan was a free man from birth and would never have acquiesced to such treatment. Of course such an origin story could be compelling if Conan overcame it, for instance by gaining his freedom through strength and character. But no, at a certain point, his master just lets a highly profitable slave go. It makes no sense and adds nothing to Conan’s rather murky character and motivations.

Conan wanders a bit, finding a sword. Then he meets a witch, who seduces him. When she begins transforming into something unsavory, he simply tosses her into the fireplace and leaves. It is genuinely funny. At that point, I wondered if this film was trying to be camp, like Mike Hodges’ 1980 Flash Gordon, which was also produced by Dino De Laurentiis.

[5]

[5]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [6]

Conan then rescues Subotai, a thief who has been imprisoned by the witch. Played by Gerry Lopez, dubbed by a Japanese actor, and named after one of Genghis Khan’s generals, Subotai is our white hero’s non-white sidekick. Because those are the rules of Hollywood: no white hero can act without a non-white sidekick.

Conan wants revenge on Thusla Doom. The witch told him that Doom can be found in the city of Zamora, so Conan and Subotai set out for there. In Zamora, they meet Valeria (Sandahl Bergman), a strong, independent female thief, because the rules of Hollywood also dictate that no white hero can be depicted without a strong, independent woman who doesn’t need him.

When Conan asks about Thulsa Doom’s snake standard, he is told of the towers of the cult of Set: “Two or three years ago, it was just another snake cult,” but now franchises are popping up in every city. At this point, I was wondering if Lorenzo Semple, Jr., of Flash Gordon and the Batman TV series fame, had a hand in the script.

The three thieves sneak into the tower of Set, where they find one of Thulsa’s heavy metal band feeding nubile females to a giant serpent. They kill the serpent, steal some treasure, and go celebrate. Conan and Valeria become an item.

Suddenly, the trio are arrested and dragged before Osric, the king of Zamora, played by the great Max von Sydow. The fact that he played Emperor Ming in Flash Gordon reinforced the camp interpretation. But then Von Sydow does something quite unexpected. He takes a campy script and gives a riveting and passionate performance. His daughter has joined Thulsa Doom’s snake cult, and he wants to hire the thieves to bring her back.

Subotai and Valeria don’t wish to risk it. When Valeria gives her case for quitting while they are ahead, again it is well-acted and touching. It is the dramatic high-point of the film, which then lapses back into camp, spectacle, and mindless action. But for a few minutes, we get a sense of the great sword and sorcery movie Conan could have been if Milius had just played it straight, with sincerity rather than irony.

Conan wants revenge, so he heads to Thulsa Doom’s headquarters alone. Milius portrays the Doom cultists as degenerate, credulous flower children being exploited by ruthless sociopaths. Using an amusing ruse, Conan steals a priest’s costume but is caught. Doom makes a rather chilling speech about the relative powers of steel and flesh. By flesh, he really means the hypnotic power of his words over the minds of his followers, which he demonstrates by enticing one to leap to her death. This contrast between words and steel is central to the whole plot, but it also dictates a fundamental change in Conan’s character. Howard’s Conan was a master of steel (well, bronze) and words. Milius’ Conan is an inarticulate thug.

Doom orders Conan to be crucified on a tree, but Subotai rescues him. Then Subotai, Valeria, and another Asian sidekick, a wizard with an annoying voice named Akiro, use magic to bring Conan back from the brink of death. The wizard warns, however, that the magic will have a heavy toll. Valeria is willing to risk it. Akiro is played by an Asian, because a white hero cannot be aided by a wise white mentor, and Morgan Freeman was otherwise engaged. Those are the rules of Hollywood.

Once Conan is restored, the three thieves penetrate the temple, where Doom is presiding over a drugged-out orgy and cannibalistic feast. (These people are really disgusting.) Conan and Co. slay the guards and capture the princess. Doom, however, transforms into a serpent and slithers away. Later, as the thieves flee down the mountainside, Doom kills Valeria with an arrow. She interprets her death as the toll for bringing Conan back.

Conan and Subotai take the princess back to Akiro’s camp, where they prepare for the onslaught of Doom’s troops. His cult consists mostly of women and hippies, so not many men are capable of carrying steel. Using guile and brutality, Conan and friends kill off Doom’s soldiers. Doom flees back to his headquarters. Having lost his steel, he will take refuge behind the flesh of his followers.

Conan follows and confronts Doom, who tries to beguile him with his hypnotic words until Conan simply chops off his head. It has all the laconic directness of Alexander cleaving the Gordian knot. Call it the argumentum ad barbarum. It is still the swiftest way to silence liars.

Deprived of their leader, the cultists conveniently disperse, even though they could have mobbed and killed Conan. Conan then burns down their temple and returns the princess to king Osric. The End.

There are many good elements to Conan the Barbarian. Schwarzenegger looks great and moves magnificently in the action sequences, which are snappily choreographed. Bergman and Von Sydow are also good. Jones is out of place, but his voice and menacing presence are used to great effect. He’s a memorable monster.

The design of the sets, weapons, and costumes is frequently excellent, particularly when inspired by Frazetta. But these elements often stray into the realm of parody. For instance, Thorgrim’s huge hammer is ridiculous.

Basil Poledouris’ orchestral score is wonderfully old-fashioned and sometimes quite good. At its best, it brings to mind Miklós Rózsa’s glittering, barbaric music for epics like Quo Vadis, El Cid, and Ben Hur.

I understand why people on the Right like Conan the Barbarian. Conan is a paleo-masculine white hero using cunning and strength to triumph in a world that is savage but also refreshingly free of liberal cant and illusions. Thulsa Doom, with his word magic and hippy cult, is a superb image of modern liberalism: honeyed words and sentimentality on the outside, devil worship, cannibalism, and perversion at the core.

But Milius’ anachronistic casting of a black villain, plus giving the white hero Asian sidekicks, is pure Hollywood diversity propaganda. Beyond that, if you are going to make a Conan movie, why stray so far from the original character? Isn’t it fraud to call such a radically different character by the same name?

A Conan film that takes the character and original stories seriously could be great. How great? Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings showed us the heights that sword and sorcery films can attain when artistry and technical skill join with fidelity to the author’s vision and genuine love of the story.

Admittedly, Howard is no Tolkien. His stories are pulps, but they are classic pulps. They are loaded with anachronisms and improbabilities of their own. All of them could be deepened and tightened. But even unaltered, every one of them is better than what Milius has dished up. I prefer sincere pulp to smirking camp every time. Conan the Barbarian is not a terrible film, but the character and the audience deserve much better.

The Unz Review [7], May, 2021

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: