Bryan Caplan’s Open Borders

Posted By John French On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledBryan Caplan

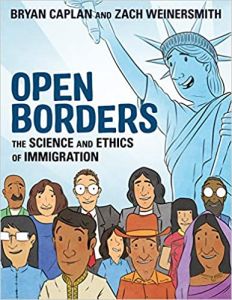

Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration

New York: First Second, 2019

Libertarians have long advocated open borders, viewing any limit on immigration as an infringement on personal liberty. To my knowledge, there has never been a book-length treatment of the issue from a libertarian perspective — until now. Bryan Caplan, professor of economics at George Mason University, makes his case for open borders in a graphic novel. Visually, the book reminds me of the For Beginners series, which uses comic illustrations to make difficult philosophical concepts easy to understand. The concepts Caplan discusses however are comparatively easy to understand and the book is opinionated. It is not an overview of the issue, but a polemic. To this reader, the artistic style of Caplan’s book had the effect of trivializing and distorting the issue. Perhaps Caplan chose this style to broaden its appeal, but it isn’t likely to win over immigration critics, who will feel their concerns have been mocked and oversimplified.

In the first chapter, a cartoon version of Caplan wonders why people from poor countries can’t migrate to first-world countries whenever they please (what he calls the “trillion-dollar question”). He pivots from this question to the claim that restrictions on immigration amount to “global apartheid,” adding that they stifle personal and global wealth. In one panel, Caplan is shown pointing at Uncle Sam and demanding to know what “moral right” the government has to regulate contracts between consenting adults. Since open borders are not the status quo, it’s not clear why Caplan thinks opponents of the policy need to shoulder the burden of proof. It’s also not a self-evident truth that people have a moral right to settle wherever they wish. It may be self-evident to Caplan, but it is not self-evident to most Americans, Canadians, Brits, Germans, Frenchmen, and Australians, who favor some form of regulation on immigration. How, then, does he know there is a moral right to migrate freely across national borders?

Caplan’s argument for this “right” is not an argument at all, but a personal preference. It rests on a thought experiment that imagines a person named “Starving Marvin,” who is starving due to a natural disaster. Marvin walks to the store to buy some food, but is held at gunpoint on the way there. If he starves, the gunman is at fault. Caplan thinks this mirrors immigration restrictions because in both cases individuals are prevented from making voluntary exchanges with other parties. Migrants wishing to settle in first-world countries may not be fleeing life-or-death circumstances, but they are prevented from bettering themselves economically. At base, their activity is no different than that of a man buying goods at a store. If it is wrong to stop a man from making a peaceful transaction with a store owner, then it is wrong for governments to stop people from entering their borders to make peaceful transactions with employers and landowners.

The issue with this type of thinking is that it assigns a status to rights that they don’t have. There has never been a time in recorded history where rights fell out of the sky and became enshrined in law. Rights are human constructs that serve various pre-determined ends (liberty, fairness, communal well-being, etc). Rights are made by people, for people. Rights don’t apply to trees, rocks, and dirt. Even so-called “animal rights” are imposed on animals by human beings. If Caplan wants to claim that there is some extralegal or transcendent source of rights, he needs to give reasons for thinking so. The right of a person to move freely across the globe proceeds from a commitment to a specific type of liberty. Caplan needs to defend that commitment before he can start talking about the right of people to immigrate to other countries.

The closest Caplan comes to making a case for the right to immigrate is in chapter 6, where he surveys different moral and religious traditions and finds that they all support open borders. But it’s not clear which perspective Caplan favors and how any of them help his case. For example, what sin is committed by someone who recognizes that Kantian ethics might not agree with immigration restrictions? If you don’t treat people as ends in themselves, what does that mean, morally speaking? Is it an offense to human dignity? If so, what is the basis for human dignity? Since Caplan is an atheist, the foundation of human dignity must be something we impose on it. How could it be anything else, since there is no God to give it value and the laws of physics and chemistry are mum on the subject? In other words, Caplan’s high-minded moral talk boils down again to his personal preferences. He needs to give a non-circular reason why his personal preferences are better than the preferences of people who wish to restrict immigration.

To ethnonationalists, the difference between a starving man trying to feed himself and entire populations moving across borders is the perceived cost. As anyone who has studied economics knows, a “cost” is anything given up for something else. Thus, Icelanders could decide that the cost of being outnumbered by foreigners outweighs the economic benefits of open borders. If Caplan wants to say that this violates the right of people to make voluntary transactions with employers, Icelanders can reply that rights are human conventions and that they don’t share Caplan’s personal preference for libertarianism.

[2]

[2]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [3]

Caplan acknowledges that migrants prefer to live around members of their own ethnic group, writing in chapter 2 that “migrants crave their countryman’s company. Chinese migrants, for example, prefer destinations with large Chinese populations.” It doesn’t occur to Caplan that natives might share this preference, too, and express it through immigration restrictions. To some people, the cost of open borders — namely, ethnic homogeneity and culture — will always be higher than the benefits. Caplan can’t prove that sacrificing ethnicity homogeneity for economic benefits is a better trade-off. How could he? Costs are subjective.

Caplan does offer an argument for open borders, but it involves so many unknowns that prudence rules against it. Caplan argues that if people from third-world countries came to the first world, it would increase global GDP because people working in the first world earn more. This is true — low-skilled workers from the third world earn more doing the same tasks in the first world because they have more high-value capital to work with. A janitor cleaning the floors of a software company in Bangladesh earns less than a janitor cleaning the floors of a Silicon Valley software firm because the capital of the Silicon Valley firm is more valuable. The value of the intellectual capital is greater (the employees went to MIT and Caltech vs. Bangladeshi universities). The land in Silicon Valley is more valuable, the patents are more valuable, and the product itself is more valuable. There is a scarcer set of inputs than there is in the Bangladeshi firm which creates greater value and higher wages for the workers.

Caplan admits that average incomes in the first world would “almost certainly” fall under open borders, but says not to fear, because it won’t cause your income to fall. He compares an influx of low-skilled workers to a group of children entering a gymnasium full of basketball players. As soon as the children enter the room, the average height falls, but that doesn’t mean the basketball players got shorter. In the same way, an influx of low-skilled workers will pull down average national incomes but won’t cause anyone’s income to fall.

The analogy fails, because Caplan doesn’t know how many people would enter the first world if caps on immigration were lifted. Caplan writes that “transportation alone is a major bottleneck” to the number of people who can immigrate, but it’s not necessary for Central and South Americans to travel by plane or bus to the United States when they can simply cross the border on foot. Africans could cross into Europe through Turkey and the Strait of Gibraltar. Under open borders, the populations of major cities could double, triple, quadruple, and beyond in a matter of years. That means more people using water, electricity, gasoline, streets, and public transportation. People use these resources in specific locales that make use of specific grids, water mains, gas pumps, streets, and land. Imagine if the population of Los Angeles doubled in 5 years. Streets would be clogged with cars. Taxi and Uber fares would increase. Utility bills would increase. The price of gasoline would increase. Rent would increase. Rising property values would lead to higher property taxes. It’s easy to see how millions of people pouring into urban areas could result not only in falling average nominal incomes, but in real incomes as well. A man who was earning $70,000 before open borders would be earning less in real terms if the cost of living rose due to immigration. I’m not saying this would happen, but it could happen, and it would leave native-born Americans economically worse off. How can Caplan guarantee this won’t happen? Rapid population growth isn’t farfetched under Caplan’s vision. The population of Sydney, Australia has grown about 15% over the last decade under a fairly restrictive immigration policy. Under no immigration policy whatsoever, the populations of major cities could explode rapidly, and along with it the cost of living, which eats into real incomes.

When Caplan turns his eye to arguments against open borders, he frequently pulls a bait and switch. He begins chapter 4 by considering how “Enlightenment ideals” and other Western concepts might go by the wayside if the West is swamped by people who don’t share them. But that’s as far as his investigation takes him. The rest of chapter 4 is about the probability of terrorist attacks, immigrant crime, and the percentage of immigrants who don’t learn the native language. What do terrorism, crime, and foreign language have to do with Enlightenment ideals and Western culture? These are not mutually exclusive categories. It’s possible for someone to be a terrorist, criminal, or foreign-language speaker and embrace these values. Caplan does the same thing in chapter 5 when answering the “Magic Dirt” objection to immigration. Caplan wonders if America would be just as wealthy if Americans were replaced by a primitive tribe of hunter-gatherers and left to start over. But Caplan avoids answering the question, saying that he believes in “magic culture,” which just means that since America is already rich, foreigners are able to exploit it to become successful.

The obvious question is why some countries are rich while others are poor. It’s no good to say that wealthy countries are wealthy due to an abundance of human and physical capital, because that just raises the question of why some countries have more robots, computers, and scientific patents than others. To his credit, Caplan analyzes the relationship between IQ and national wealth, but suggests that “reverse causation” may be at play, whereby nutrition, education, and healthcare raise IQ. But if wealth raises IQ, as Caplan claims, how did anybody get wealthy in the first place? Did the people in today’s wealthiest countries get access to proper nutrition, education, and health, and then become rich? It’s impossible to say exactly how countries become rich. Since Caplan doesn’t know the specific causes of national wealth, isn’t it better not to tamper with it by mixing populations?

It’s hard to imagine someone who doesn’t have strong feelings about immigration being swayed by Caplan’s reasoning, let alone ethnonationalists and others who want tougher immigration laws. When he chastises opponents of immigration on moral grounds, what he is really saying is that they are bad libertarians. But what is the point of that if the book was written to persuade non-libertarians to adopt his view? The most one can say for the book is that it will amuse libertarians, but leave everyone else unmoved.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: