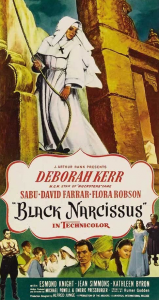

Black Narcissus

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledMichael Powell (1905–1990) is one of the tragic geniuses of film: a genius because he is one of the most visually dazzling directors in the history of cinema, tragic because he too often wasted his talents on inferior scripts, most of them provided by his longtime collaborator, Emeric Pressburger, a Hungarian-Jewish refugee to whom Powell often gave co-director credit.

Powell worked his way up from a studio gofer to a leading director. Many of his journeyman efforts are lost. His career as a mature director begins in 1937 with The Edge of the World. With the exception of The Edge of the World and I Know Where I’m Going (1945), Powell spent his first ten years churning out anti-German, pro-cosmopolitan war propaganda, visually and technically dazzling but often quite silly: The Spy in Black (1939), Contraband (1940), 49th Parallel (1941), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), and A Matter of Life and Death (1946). Powell also directed a number of short propaganda films for the British government with titles like The Lion Has Wings (1939), An Airman’s Letter to His Mother (1941), and The Volunteer (1943).

Powell’s genius only flourished fully after the war, in such apolitical works as Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948), which is one of my favorite films. Aside from The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), an adaptation of Jacques Offenbach’s opera of the same name, most of Powell’s films in the 1950s were mediocre. Then he produced one last masterpiece, Peeping Tom (1960), the story of a serial killer which was so shocking and distasteful that it pretty much destroyed his career.

Black Narcissus is based on the 1939 novel of the same name by [Margaret] Rumer Godden about a small group of Anglican nuns who set up a convent and school in Mopu, a princely state in the Himalayas. The local potentate, General Toda Rai, gives the sisters an abandoned palace, a former harem decorated with erotic art, perched on the edge of a dizzying precipice with a magnificent view of the Himalayas. Near them is a Hindu holy man, who turns out to be the former owner of the palace. Below them is a bewilderingly complex, violent, and superstitious society. Their only guide is Mr. Dean, an Englishman who manages a tea plantation for the General.

Black Narcissus seems, in part, to be about what can be called “the spirit of place,” understood in terms of landscape, culture, and even human structures. The nuns are all European women, and even though they have already spent some time in India, they seemed to have been relatively cloistered, whereas in Mopu, they are on their own, founding a new convent. Beyond that, the atmosphere in Mopu is particularly potent, bringing each member of the order to a crisis.

Sister Briony, known for her strength, becomes sick due to the high altitude. Sister Philippa, who was brought to tend the vegetable gardens, is overwhelmed by the beauty of the place and plants flowers instead. Sister Honey’s soft-heartedness leads her to give medicine to a fatally ill baby, against the advice of Mr. Dean, who knows that the locals will blame the sisters for the child’s death, which will endanger their mission and perhaps their lives.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [3]

The most dramatic crises, however, are those of Sister Clodagh, the young Sister Superior, and Sister Ruth, who is both highly neurotic and affected by the high altitude. Both Clodagh and Ruth are prideful women, which pits them against one another from the start. Beyond that, both women are stirred by the palace’s erotic history and décor, as well as the presence of a highly attractive bachelor, Mr. Dean, into an increasingly conscious sexual rivalry. Dean too, for his part, is clearly attracted to Sister Clodagh, although at first they both seem to hate each other. Dean is also dismissive of the Sisters’ Christian faith and mission. Toss in a budding romance between the General’s son, who is being tutored by the Sisters, and a nubile vixen of the lowest caste who lives at the convent, and you have a simmering cauldron of sexual tension that soon boils over, with disastrous results.

The story’s combination of aestheticism, eroticism, and riveting dramatic conflicts inspired some of Powell’s best work. From start to finish, Black Narcissus is visually ravishing, with tension and suspense mounting until the viewer feels, like Sister Ruth, that he is losing his mind. As the story unfolds, the production becomes increasingly stylized, from the stark simplicity and Vermeer-like light of the scenes before the nuns depart for Mopu, to the voluptuous colors and décor of the palace, to pure German Expressionist horror at the end. The music by Brian Easdale, who also composed the music for The Red Shoes, is some of his finest work. The cast is excellent, with outstanding performances by Deborah Kerr as Sister Clodagh, David Farrar as Mr. Dean, and Kathleen Byron as Sister Ruth.

Black Narcissus was filmed in Technicolor entirely on soundstages, except for some scenes in a London botanical garden, because of Powell’s desire to meticulously control light and color. Some of the matte paintings look fake, but one is more forgiving when one realizes that practically everything else you took for real is fake as well.

Black Narcissus was released in 1947, when the British Empire was pulling out of India. In that context, a story about British nuns going mad because they are “out of place” in India was taken as anti-colonialist, anti-Imperialist propaganda. That may well have been Pressburger’s intent. As an ethnonationalist, I don’t have any problem with an anti-imperialist message. But I doubt it occurred to Powell, or to the original novelist, that Black Narcissus was about much more than sex.

The Legion of Decency in the US regarded Black Narcissus as anti-Christian and demanded a flashback to Sister Clodagh’s life before becoming a nun be removed. Clodagh came from a wealthy Anglo-Irish family. From childhood, she thought she would marry her sweetheart Con. When she discovered that he planned to go to America and leave her behind, she decided to take her destruction into her own hands and become a nun. She engineered an honorable defeat [4] for herself.

I don’t see anything anti-Christian about acknowledging the fact that some people join religious orders out of disappointment with the world. Nor does it strike me as anti-Christian to acknowledge the fact that celibacy often leaves a lot to be desired.

The deeper message of Black Narcissus is not about sex but about race. Mr. Dean did not lack opportunities for sex in Mopu. Nor were Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth shut away entirely from men before coming to Mopu. They were constantly surrounded by the natives, after all. What upset the plans of all three was not the presence of a member of the opposite sex, but of a member of the opposite sex of the same race.

Each time I watch Black Narcissus, I prize it more highly. I have avoided spoilers, because I want you to watch it too. But be sure to seek out Michael Powell’s Black Narcissus, because there is now a pretender to the title. In 2020, a three-part British miniseries of Black Narcissus was run on BBC One and FX.

Frankly, I dreaded watching it, wondering how it would be spoiled by political correctness. Fortunately, the production is marred in only one place. When Mother Dorothea (Diana Rigg in her last role) dispatches the nuns to Mopu, she tells Sister Clodagh to take Sister Philippa with her, to depend on for her skill as a gardener — and for her wisdom. This time, however, the wise Sister Philippa is played by a black woman.

The rest of the production is pretty much by the book and helps one appreciate Pressburger’s script, which removed only inessential clutter. The cast, sets, and music are all first rate. Gemma Arterton plays Sister Clodagh, and Alessandro Nivola plays Mr. Dean, with real chemistry between them.

The only improvements are a lack of fake-looking effects and Aisling Franciosi’s portrayal of Sister Ruth. In Powell’s film, you know that Kathleen Byron’s Sister Ruth is trouble right from the start. Franciosi’s Sister Ruth seems sweet and vulnerable at first and only slowly goes mad. It is interesting to see her character develop.

Most importantly, the underlying racial dynamic and message remain unaltered. White people have explored the whole planet, running toward wealth, knowledge, and adventure — or merely running away from trouble and heartache. But no matter the forces that drive us apart, Black Narcissus shows that nature is stronger, that blood is thicker than water — even holy water — and that like seeks like in the end.

The Unz Review [5], April 30, 2021

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: