Within Our Gates: The ”Black Birth of a Nation”

Posted By Travis LeBlanc On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledIn my life, I have encountered people who enjoy watching bad movies. I don’t mean that they have bad taste in movies, but that they revel in watching objectively terrible, often low-budget movies in an MST3K sort of way. I guess they find something endearing about the amateurish charm.

I mean, knock yourself out. But I’ve never quite understood this. I am going to die without watching all the movies I want to watch or reading all the books I want to read, so I couldn’t imagine taking time out of my life to watch something that I know is bad.

There are two exceptions, though.

The first is if it looks nice. If a movie is visually pleasing enough, I can sometimes overlook a stupid plot or annoying acting. I might turn off the sound, put on some music I like, and enjoy it as an aesthetic experience.

The other way I can enjoy a bad movie is if it is a time capsule. Oh, I love me a good time capsule. Certain movies only could have been made at a very specific time and/or place. I can watch a good time capsule even if it is bad because I at least feel like I’m learning something. Liquid Sky is one of the worst movies I have ever seen in my life, but I’ll be damned if it is not a fascinating snapshot of New York City in the early 80s.

I particularly like movies about a contemporaneous short-lived fad, like a movie about disco [2] made during disco, or a movie about the late 70s roller skating craze [3] made in the late 70s.

You could make a movie today set in the disco era, have all the sets, costumes, hairstyles, and slang perfectly accurate for the period, but it still wouldn’t be the same. People who make movies set in the past will project modern values and biases onto them. In some ways, that’s unavoidable.

But more importantly, all movies set in the past are tainted by hindsight. The people who made it know how the story ends, and that influences the way they tell the story. Anyone who makes a movie about WWII does so knowing that the Allies win in the end, whereas the people who made Casablanca didn’t know. When Casablanca went into production, the Battle of Stalingrad hadn’t even started yet. It was a movie about war made in the fog of war.

The appeal of the time capsule is that there a certain immediacy that can’t be replicated by anyone who comes after.

Today, we’re going to be cracking open a time capsule from 1920. The movie is called Within Our Gates — and it is a real humdinger of a time capsule.

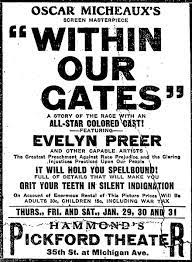

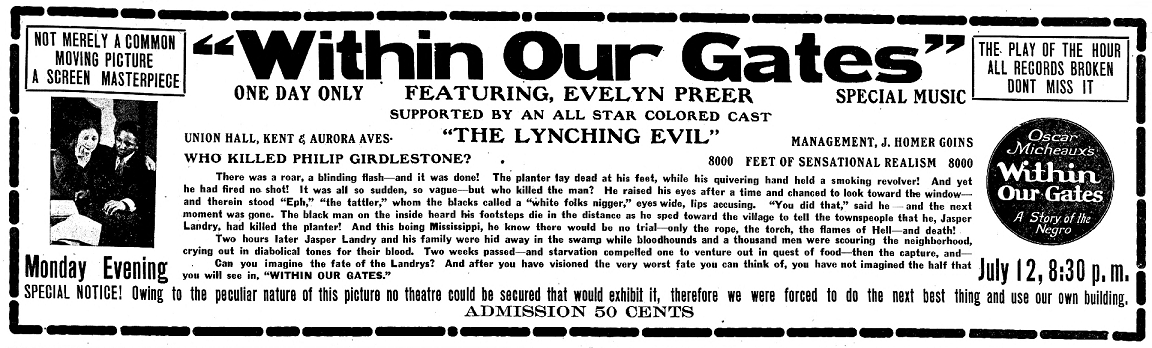

Within Our Gates is an interesting movie for a few reasons. Most people are interested in it because it is credited as being the oldest surviving movie made by a black director. The director, Oscar Micheaux, had made one previous film called The Homestead which is now sadly a lost film, like 90% of all silent films. Indeed, Within Our Gates was also considered a lost film for many years until a copy of it turned up in Spain in the 1970s.

Anyway, that’s not why it’s interesting to me.

Within Our Gates interests me is because it’s a movie about the Great Migration of blacks from the South to the North that was made during the Great Migration. Perfect time capsule material.

Secondly, it was released only 55 years after the Civil War, when wounds were still fresh. When this movie came out, there were still a lot of Civil War veterans and former slaves walking around. Slavery was as recent for people in 1920 as segregation is for people today. Most Baby Boomers can remember segregation. Maybe they don’t like to talk about it, but most boomers can remember seeing “Whites Only” signs as a kid and a lot of them spent at least part of their education in segregated schools. You may be too young to remember segregation, but you probably know someone who does.

Since it was released, Within Our Gates has been viewed as the black answer to D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, because it turned the tables and presented whites as unflatteringly as Griffith’s film portrayed blacks, showing whites to be the real bloodthirsty savages. It also dwells on the sharp cultural and social divides between the North and South which were still very pronounced in 1920 and not inconsiderable even today. Micheaux himself denied that responding to Griffith’s film was his intention, saying he was just trying to discuss issues affecting blacks. But the comparisons have persisted through the years.

Oscar Micheaux is an interesting guy. Even I, a heartless racist, have to respect his hustle. He was born in 1884, the son of a former slave and the fifth of 13 children. Micheaux was a devotee of Booker T. Washington (to whom he dedicated his first novel) and appeared to be something of a talented 10th. He was uncharacteristically good at saving money and had a knack for networking. He started his own shoeshine business as a teenager before landing a job as a railway porter, which was a pretty high-status job for a black guy in those days. The job allowed him to travel and observe the different conditions of blacks in various parts of the country, as well as make valuable connections with sympathetic academics and businessmen.

One of the questions of Micheaux’s day was whether or not blacks should leave the rural South and go to the urban North. Micheaux thought country life in the South was bad for blacks because of all the racism, but life in Northern cities also had its problems with crime and degeneracy. Micheaux believed that blacks should go West and build their own communities, but found few takers. He had a go at homesteading in South Dakota for a while, but once while he was away on business, his wife drained his bank account, his father-in-law sold all his property, and both vanished into the night.

Micheaux eventually settled in Chicago, started writing novels, and then later got into film making. He made 44 films, most of them silent, but some were early talkies. Paul Robeson, who would later break through into Hollywood films in the 1930s, started out in Micheaux movies.

At the time, Hollywood was not yet the uncontested film capital of America. Fort Lee, New Jersey was still producing movies. There was a significant film industry in Chicago, and there was a rather intense rivalry between Chicago and Hollywood for dominance of the increasingly profitable movie business. Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson both started their movie careers in Chicago. Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst had an interest in seeing Chicago win out and would flood his papers with negative stories about Hollywood. It was a lot of the motivation by the public crucifixion of Fatty Arbuckle [6] in the 1920s.

Within Our Gates stars Evelyn Preer as Sylvia Landry. Preer was Micheaux’s leading lady in his early films. A relatively unknown vaudeville performer at the time, she would become the first celebrity black actress. By the end of her life, she had worked her way up to playing bit parts in mainstream Hollywood movies. Her last film was an uncredited role in the Marlene Dietrich movie Blonde Venus. She would die in 1932 at age 36 due to complications following childbirth. Her daughter would grow up to become a Catholic nun who has a Wikipedia page [8] for some reason and is still alive.

With the background out of the way, let’s get into this movie.

The opening intertitle begins: “At the opening of our drama, we find our characters in the North, where the prejudices and hatreds of the South do not exist — though this does not prevent the occasional lynching of a negro.”

Well! Right out of the gate, Micheaux is throwing down the gauntlet. Yeah, some whites are worse than others, but at the end of the day, you can’t trust any of them.

The first camera shot we get is of Evelyn Preer sitting at a desk in what appears to be a comfortable middle-class living room. She is introduced in the next intertitle: “Sylvia Landry — a schoolteacher from the South visiting her northern cousin — is typical of the intelligent Negro of our time.”

The story begins in Boston, where Sylvia’s cousin Alma lives. We are told that Alma is a divorcee. In 1920, divorce was still relatively rare, and so audiences at the time probably would have read things into that, possibly that she was unfaithful. Back then, if you got a divorce, it was assumed that you had a pretty damn good reason. Also hanging around is Alma’s no-good stepbrother Larry “the Leach” Prichard, who is a notorious gangster of ill repute.

Sylvia is engaged to a fellow named Conrad. Larry and Alma are not too pleased about that, because Alma is secretly in love with Conrad and Larry quite fancies Sylvia for himself. So we’ve got a sort of love square going on. Is that what it’s called?

Before I continue, I should point out that all four of these people are light-skinned blacks. They can’t pass for white, but you can tell they have high levels of European admixture. Their stylish clothes also suggest that they are fairly well-to-do by the standards of the time.

Micheaux’s movies are not just about white and black, but also deal with the relationship between dark-skinned blacks and light-skinned blacks. At the time, the black elite was overwhelmingly mulatto, and many of them descended from free blacks. There was a lot of mutual resentment between the two. Dark blacks saw light blacks as stuck-up, unreliable as allies, and lacking in racial pride. And light-skinned blacks resented being lumped in the same group as dysfunctional dark blacks. In some places, free blacks had fewer rights after the Civil War than before. Whites could handle a few blacks hanging around, but once they were flooded with ex-slaves, they enacted a lot of segregation laws.

Micheaux, who himself was quite dark, was criticized throughout his career for favoring light-skinned blacks as leads. But can you blame him? They were probably smarter and easier to work with. He’s making movies on a shoestring budget. He can’t afford to do a million takes. He needs smart people who can do it right the first time, so he gets mulattos. Others accused Micheaux of portraying dark-skinned blacks less favorably, casting them as criminals and ne’er-do-wells. To his credit, Micheaux does not sugar-coat his own people’s failings. He acknowledges there are bad people among his people and presents them as examples of how not to be.

OK, back to the story.

A telegram from Conrad is sent to Sylvia, but is intercepted by Alma. The letter says that he will be arriving that evening. Rather than giving the letter to Sylvia, she hides it.

Meanwhile, Larry goes to a poker game with his gangster friends. They are joined by Red, a professional gambler. The game is actually rigged, and the whole point is to take Red for as much money as they can. Red notices the scam, but before he can reach for his gun, Larry and his gangster friends shoot him dead.

At the same time, Sylvia wakes up from a nightmare. Larry comes home and tells Sylvia and Alma that he has just killed a man. Sylvia then reveals that her nightmare was about Larry killing someone. This is the weirdest part of the movie: it implies that blacks are psychic. There are two more times in the movie where someone dies and one of the blacks has a vision about it while it is happening. If it were Sylvia doing it all three times, you might just think that Sylvia is psychic, but Alma also does it once, and Sylvia’s mom does it, too. Are all black women psychic? Maybe it runs in the family. Magic negro? Nah. These are psychic negros.

Later that day, Conrad shows up, but by then, the scheming Alma has arranged for Conrad to catch Sylvia alone in a room with another man. While Sylvia was not doing anything unsavory, Conrad flips outs, dumps her, and takes off to Brazil. Heartbroken, Sylvia returns to the Mississippi.

So far, all we have is a melodrama. Don’t worry. It’s about to get political.

As the intertitle tells us: “Some time later. Far from civilization and in the depths of the forests of the South, where ignorance and the lynch law reign supreme, we find the hamlet of Piney Woods and the school for negros.”

Here we meet Reverend Jacob, the founder of the school and “apostle of education for the black race.” We also meet his sister Constance, “Reverend Jacob’s sole ally in his unequal struggle against the Negros’ ignorance.”

A poor black father and his two kids visit Reverend Jacobs, all of them wretched-looking creatures and midnight black, making it clear just how light-skinned the leads are.

The black father tells Reverend Jacobs, “I hears ‘bout your school — ‘n’ so we walked from my place, a ways off, ‘cause my children don’t do nothin’ but say, ‘Papa, without schoolin’, we c’n never ‘mount to nothin’.”

How come black children these days never say stuff like that?

“. . . so here I is, suh, ready ta work day ‘n’ night so’s my children c’n get schoolin’ ‘n’ be useful to society.”

Just watching this, I feel bad for the black identitarians of that era. If only they could see the state of things today. Blacks back then wanted an education, but couldn’t afford it. Nowadays, it’s free. The hardest part is getting them to go, and the second-hardest is getting them to behave when they are there.

Sylvia accepts a job at the negro school, and with her marriage called off, appears to throw herself into black identitarianism. But trouble soon hits when the school runs low on money. There are too many students, and Reverend Jacobs is just too big-hearted to turn away the new kids who keep coming in.

An interesting thing about this movie is how race is talked about. After being told of the school’s money problems, the next intertitle reads “During that sleepless night, she could think of nothing but the eternal struggle of her race and of how she could uplift it.” The next day, Sylvia goes to Reverend Jacobs and tells him “It is my duty and the duty of each member of our race to destroy ignorance and superstition.”

Duty? Eternal struggle? It sounds kind of fascist.

For what it’s worth, Marcus Garvey openly identified with the term “fascist.” More than identified — he claimed he invented it. “When we had 100,000 disciplined men, and were training children, Mussolini was still unknown. Mussolini copied our fascism.”

We wuz il Duces.

Sylvia decides to go back up to Boston to see if she can find a wealthy benefactor to put up the money to save the school. Here, we are introduced to Dr. V. Vivian, who will become Sylvia’s new love interest. Now, this guy looks totally white to me. He looks white, he has straight hair, and he’s a fucking doctor. What the hell else am I supposed to think?

As I was watching his romance with Sylvia pick up, I thought he was one very open-minded white guy for 1920. He must think Sylvia is white, but will later find out that she is part black, and that is going to create some conflict later on.

Actually, no. It wasn’t until I read up on this movie later that I found out that Vivian is supposed to be black. I mean, sure. An octoroon can look as white as that guy, and an octoroon would have been considered legally black back then. But how the hell was I supposed to know that? The intertitles never tell you. They just expect you to know that’s a black guy.

Maybe people in 1920 had really good black-dar and could detect even small traces of African admixture. It’s possible. During the silent film era, a lot of people became expert lip-readers from watching so many movies with no talking. So, maybe in a society that was racialized like 1920s America, people just got really, really good at seeing even tiny traces of blackness.

Anyway, Dr. Vivian is standing in his office, looking out the window, when he sees an unscrupulous negro steal Sylvia’s purse. He runs out of his office, catches the thief, and returns the purse. The two hit it off, and the unscrupulous negro gets hauled away by a cop.

Here, we are introduced to our first white characters: two old ladies, one good and one bad. One is a fiercely racist Southerner, and the other a benevolent Northerner.

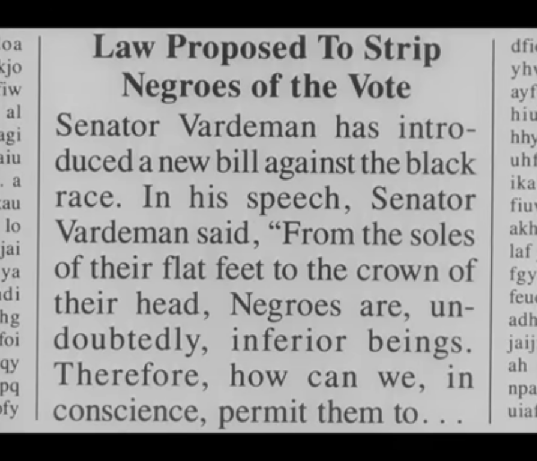

The first is, as the intertitles tell us, “Mrs. Geraldine Stratton, a rich Southerner passing through Boston — a bitter enemy of woman’s suffrage because it appalls her to think that negro women might vote.”

When we first see Mrs. Stratton, she is shown reading the following news story. . .

. . . and then nodding approvingly.

For those who don’t know, the “Vardeman” mentioned in the article is one-term Mississippi senator James K. Vardaman [14], and his power level was off the charts. Known as “The Great White Chief,” Vardaman was the first Mississippi senator to be elected by popular vote after the 17th Amendment was passed, and he did so by running on a platform of revoking the 14th and 15th. His platform was literally “vote for me and I will take away black people’s right to vote” and he won. He was also openly pro-lynching, famously stating that “If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy.”

If any normie conservatives are reading this, yes, he was a Democrat.

Vardaman’s political downfall was due to being one of only 6 senators to vote against U.S. entry into WWI. While buyer’s remorse would set in later, WWI was an extremely popular war at the time. There were also rumors floating around that Germany was plotting to instigate a black uprising. Vardaman was primaried out in 1918, so he was no longer a senator by the time Within Our Gates was released. However, there is one point in the movie when someone is seen reading a magazine about the death of Teddy Roosevelt, which suggests that the movie takes place in early 1919 in Vardaman’s last months in the Senate.

The other white woman is described by the intertitle as “Mrs. Elena Warwick, a philanthropist.” That’s it.

Mrs. Warwick’s introduction is a bit more dramatic. Sylvia is sitting on a bench, bummed out that she hasn’t met any rich people yet. The school is doomed. Suddenly, she sees a white kid about to be hit by a car. She runs out, pushes the kid out of the way, and the car hits her instead. Out of the car steps Mrs. Elena Warwick.

It’s pretty deus ex machina. Sylvia goes to Boston in search of a wealthy benefactor and gets hit by a car that just so happens to be owned by one. Oh well. It’s a movie. Just run with it.

Mrs. Warwick visits Sylvia in the hospital, and Sylvia tells her all about her problems. Sylvia tells her that she has to get $5,000 in the next ten days, or else the school for negro children will close. Mrs. Warwick is sympathetic and agrees to help the school. Sylvia is delighted.

But. . .

Before Mrs. Warwick breaks out her checkbook, she decides to call upon her good friend Mrs. Stratton for her advice on the matter. Mrs. Stratton is a Southerner, and as such, knows a thing or two about negros, especially the kind you find down there in Dixieland. Mrs. Warwick would like to pick her brain. When Mrs. Warwick informs Mrs. Stratton of her intention to fund the negro school, Mrs. Stratton poo-poos the ideas with a string of delightfully racist observations.

“Lumber-jacks and field hands.” Mrs. Stratton says.

Let me tell you — it is an error to try and educate them. Besides, they don’t want an education. Can’t you see that thinking would only give them a headache? Their ambition is to belong to a dozen lodges, consume religion without restraint, and, when they die, go straight up to Heaven. Wasting $5,000 on a school is plain silly when you could give $100 to old Ned, the best colored preacher in the world who will do more to keep Negroes in their place than all your schools put together.

Ah, Ned. Here’s where we meet Old Ned. He only gets one scene, but it’s the best scene in the movie.

In addition to his preference for light-skinned leads, another one of the black community’s biggest criticisms of Micheaux was his harsh portrayal of black clergy. Micheaux was a strong critic of religion — or more specifically, blacks’ distinct brand of over-the-top religiosity and blacks’ over-reliance on clergy for leadership. Christianity never really challenged segregation, but it made blacks feel okay about being losers. Old Ned is the character Micheaux created to illustrate this point.

Here we see Old Ned standing before his congregation. His sermon is given over several intertitles:

The text of my sermon this morning will be Abraham and the Fatted Calf. Behold, I foresee that black people will be the first and will be the last. While the white folk, with all their schooling, all their wealth, all their sins, will most all fall into the everlasting inferno. While our race, lacking those vices and whose souls are more pure, most all will ascend into Heaven. Hallelujah!

Old Ned is going out there and telling blacks that it is actually a good thing that blacks are dumber and poorer than whites. Don’t bother improving yourself. Just put in your three-score plus ten years and then go to heaven. He then starts jumping around and doing the whole animated black preacher thing.

Here’s the punchline. On Monday morning, Old Ned goes to visit a couple of white guys. It turns out that he’s on the white man’s payroll.

After all his denunciation of whites, when he is in their presence, Old Ned is deferential, servile, and willing to play the fool. One of the whites shows Old Ned a newspaper article, and asks his opinion. “It’s about the Negroes’ right to vote. We are all in favor of your people — but we can’t be havin’ Negroes voting.”

Old Ned reads the article and says “Y’all knows what I always preach. This is a land for the white man and black folks got ta know their place. Let the white man go to Hell with his politics, wealth, and sins. Give me Jesus. Leave it to me gen’men. I always preach that the vices and sins of the white folk will end them up in Hell. When the Judgement Day comes, more Negroes than whites will rise up to Heaven.”

Ah, Ned. He’s an Uncle Tom’s Uncle Tom. The white men are pleased with Old Ned’s answer. Even though Old Ned’s sermons are viciously anti-white, it is worth it for the white guys to support it, because it has the effect of pacifying the blacks.

Here’s the double punchline. Old Ned is not just a traitor. He’s a self-conscious fraud. After Old Ned leaves the room, his smile evaporates, his expression changes to one more somber, and he says “Again, I’ve sold my birthright. All for a miserable ‘mess of pottage.’ Negroes and whites — all are equal. As for me, miserable sinner, Hell is my destiny.”

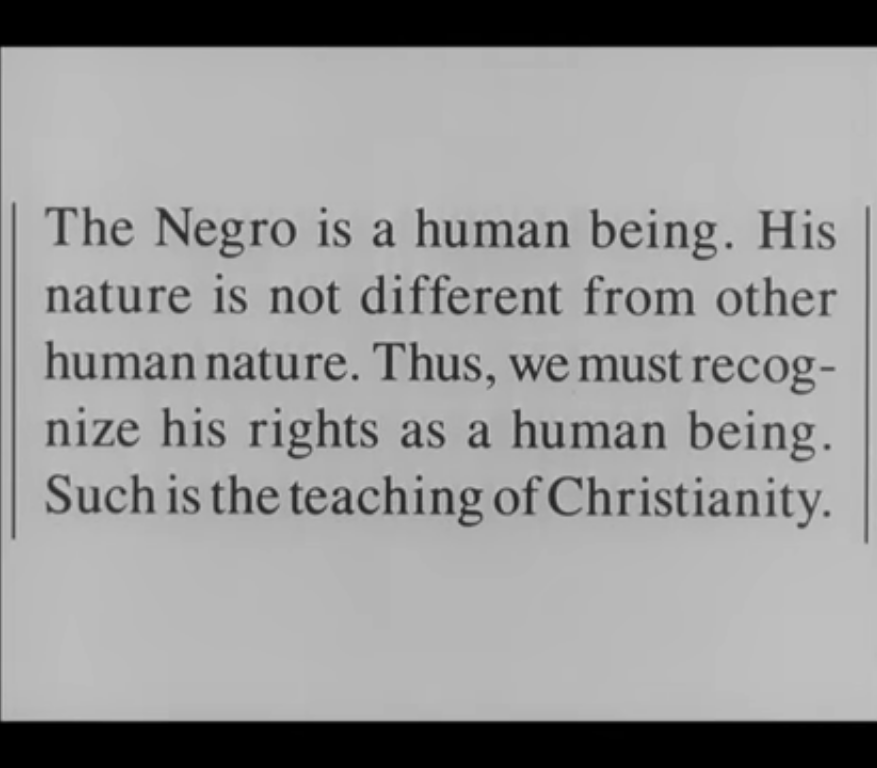

After giving Christianity a sound thrashing, Micheaux tries to cushion the blow by inserting another scene where Dr. Vivian is reading a book and comes across this passage:

I’m not sure what Micheaux’s true feelings about religion are, but I imagine he shoehorned this scene in to humor the censors who might have banned the film outright if it were deemed too anti-Christian.

Back to the narrative.

Mrs. Warwick, having been persuaded by Mrs. Stratton, informs Sylvia that she has changed her mind about funding the school. But then, roughly one minute later, she changes her mind again and informs Mrs. Stratton that she is not only going to fund the school, but that she will be donating $50,000 rather than the $5,000 that was asked for. Mrs. Stratton leaves in a huff.

Sylvia, having completed her objective, goes back home to Mississippi. Once there, Reverend Jacobs proposes to her, but by then, Sylvia is in love with Dr. Vivian.

Back in Boston, Larry the Leach is running low on cash, so he decides to do some burglary. But while in the middle of cracking a safe, a detective who has been following him around for the whole movie confronts him. A gunfight ensues and Larry is fatally wounded. As he flees from the scene, he bumps into Dr. Vivian and dies in his care. It is here when Alma has a psychic premonition that something terrible has happened.

Larry dies in Dr. Vivian’s care which leads him to meeting his next of kin: Alma. Alma then reveals to Dr. Vivian the truth of Sylvia’s back story. Sylvia was adopted by a black family by the name of Landry, who were all lynched by evil whites. Most of the rest of the movie is a flashback.

Here’s where the anti-whiteness gets dialed up to 11.

Sylvia is adopted by the jet-black Landry family. They are poor, illiterate farmers. Sylvia, however, has been to school. Now that they have someone in the household who can read and do math, she can help her father Jasper with his business dealings.

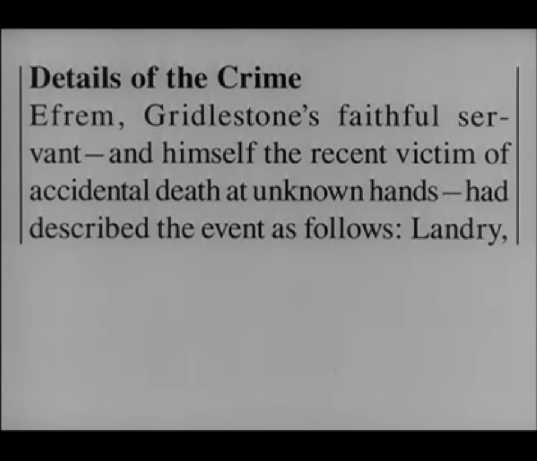

This is a problem for their wicked landlord Philip Gridlestone. As obsequious Uncle Tom manservant Efrem puts it, “Dat Landry gal been ta school ‘n’ keeps her pappy’s books now — so ya won’t git ta cheat him no mo.”

[19]

[19]Efrem, who presents himself as undyingly loyal to Gridlestone, is shown stealing Mr. Girdlestone’s liquor.

The next day, Jasper goes to Mr. Gridlestone’s house to make his payment while Efrem spies on them through a window outside. Here’s where it starts getting silly. When it becomes clear that the jig is up and Gridlestone can’t rip Jasper off anymore, Gridlestone starts on a racist rant and punches Jasper. He then proceeds to pull a gun out of his desk. Why? He can’t rip him off anymore, so he’s just going to kill him? I’m sure it pisses him off, but he’s rich. But wait. It gets sillier.

While the confrontation between Jasper and Gridlestone escalates, some unnamed white guy with a rifle comes creeping up the side of the house. The intertitle tells us: “Yes, Gridlestone had cheated him, also, and when he had come to terms, had laughed in his face, calling him ‘poor white trash — and no better than a Negro’ whereupon he had sworn. . .”

This unnamed white guy has come to kill Gridlestone because Gridlestone had compared him to a black person. Even though what is about to happen is a white-on-white murder, the guy’s motive is still rooted in hatred for blacks. If the dude didn’t hate blacks so much, being compared to one wouldn’t have ruffled his feathers so much.

As Jasper and Gridlestone wrestle over the gun, the unnamed white guy shoots Gridlestone through the window, killing him at the exact moment when Jasper takes the gun out of Gridlestone’s hand.

Efrem was watching through the window, but apparently didn’t see the white guy and had his back turned when the shot was fired. Efrem turns around and sees Gridlestone shot with Jasper holding the gun in his hand. Efrem then runs to town and starts telling every white person he can that Jasper Landry has killed Mr. Gridlestone, and the whites begin putting together a lynching party. Jasper is about to be killed for a white man’s crime.

Pulling out the gun was silly enough, but how unlucky do you have to be to visit your landlord at the exact moment that someone has come to murder him? It sounds like the kind of lie that a guilty black person would make up after being caught red-handed. “I dindu nuffin! I just went to go pay my landlord but then he pulled a gun on me for no reason. I took the gun out of his hand but then some white guy shot him through the window.”

Back at the Landry home, Sylvia’s mother starts crying. Sylvia goes over to her to see what is wrong, and her mother says “I know you’re gwine ta laugh a’ me, but I’se the feelin somethin’ ter’ble has happened.”

What is it with these psychic negroes?

Eventually, Jasper comes home and the Landry family goes on the run into the swamplands while the lynch mob gears up for a manhunt. The real killer of Philip Gridlestone gets killed by men who thought he was Jasper when he is seen stealthily crawling through the bushes. I assume he thought the manhunt was for him.

As the intertitles inform us, “Efrem is in his glory”. The Uncle Tom is the center of white attention, and he values nothing higher. “T’ain’ no doubt ‘bout it — da whi’ fo’ks loves me. Here I is ‘mong da whi’ da whi’ fo’k, while dem other niggahs hide in da woods.”

But it would turn out that Efrem had spoken too soon. Right after that, a white guy says to another white guy: “The people are getting impatient.” And shortly after, the same guy says “While we’s waitin’, what ya say we grab this boy?” gesturing over to Efrem.

The mob was hungry to start killing some blacks, but they couldn’t find the guilty ones, so they give them Efrem to satisfy their bloodlust — an appetizer lynching before the Landry family main course. Efrem tries to plead: “Bu. . . bu. . . bu’ you knows me, Mistah John — ya knows I’se da one wha wole you Landry killed Mistah Gridlestone.” But his pleas fall on deaf ears. The mob takes Efrem away and hangs him.

I know racism was a big deal back then. I know lynchings were a thing. But I have a hard time believing that people were just going around and lynching blacks just for the hell of it. And that’s why they kill Efrem: for the hell of it. It’s silly, but it makes sense from a propaganda perspective. Micheaux wants to send a message that being a race traitor doesn’t pay. I would do the same if I were him, but I would try to make the traitor’s demise more plausible.

The Landry family is eventually found while Sylvia is away getting supplies. Mom and dad have nooses put around their necks. Their son and Sylvia’s little brother manage to escape the mob and get away on horseback. Probably just as well, as I don’t think depicting a child getting lynched would have gotten past the censors. His fate is never revealed.

Meanwhile, Sylvia is hiding out with relatives. However, while she was out, she was spotted by Philip Gridlestone’s brother, Armand Gridlestone. Armand follows Sylvia back to her hiding place and starts trying to rape her.

This is the climax of the movie and its most famous scene. Here you see quick cutting back and forth between scenes of the Landrys being hung and Gridlestone sexually assaulting Sylvia.

But before Armand can actually start raping Sylvia, he notices a scar on her chest. He recognizes that scar, and realizes that Sylvia is actually his daughter.

Look, it’s a movie. Just run with it.

It is further revealed that Sylvia was the legitimate daughter of interracial marriage with a black woman. Well, Sylvia, I’ve got good news and bad news. Bad news: your parents are dead. Good news: you are not a bastard. Bad news: your father is a rapist. Good news: despite your father being a rapist, you were still conceived in love.

Honestly, I like that twist. “Race mixers are also rapists” is a message I can get behind.

It is also revealed that Armand was the one who was paying for her schooling all along.

We then cut back to the present day with Alma and Dr. Vivian sitting together, Alma having now finished the story.

First of all, I would like to know how Alma knew the real story of what happened. The four people present at the murder of Philip Gridlestone (Jasper, Efrem, Gridlestone, and the unnamed white guy) all ended up dead, and only the unnamed white guy really knew what happened. So how did Alma know? There are a few plot holes throughout the movie, but it is known that some scenes were edited out for the censors. Maybe some of the plot holes were explained in the cut material, but this is a huge plot hole. (This also lends credibility to my theory that the story is some bullshit made up by a guilty black guy who got caught red-handed.)

The closing scene of the movie is where Dr. Vivian has tracked down Sylvia and is trying to persuade her to be proud of her country. He does so by listing the military achievements of blacks in the service of Uncle Sam, implying that by hating the country, you are wiping out those accomplishments. “Be proud of our country, Sylvia. We should never forget what our people did in Cuba under Roosevelt’s command, And at Carrizal in Mexico. And later in France, from Bruges to Chateau-Thierry, from Saint-Mihiel to the Alps. We were never immigrants!”

Well, that last line is kind of problematic. Why is never being an immigrant something to take pride in? Are you saying there is something wrong with being an immigrant? I think Oscar Micheaux needs be canceled before he inspires a mass shooting.

“Be proud of our country, always!” says Dr. Vivian. “And you, Sylvia, have been thinking deeply about this, but unfortunately your thoughts have been warped. In spite of your misfortunes, you will always be a patriot — and a tender wife. I love you!”

They then go off and get married.

I thought this was kind of a weird way to end the movie, and that it was inserted in for the benefit of the censors. You have to throw in some pro-America statements so you don’t look like a commie.

It’s funny to compare it to D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. People will look at Birth of a Nation and talk about how Griffith is a racist. But they will look at a guy like Micheaux, and say “Oh man, he’s holding a mirror up to society. He’s just calling it as he sees it.”

But as an identitarian studying the work of another identitarian, I recognize some of the propaganda and persuasion techniques that are going over the heads of people who take it at face value.

Within Our Gates is one of those movies where I’m not sure I liked it, but I’m glad I watched it.

It is, if nothing else, different.