Seneca on Keeping Cool

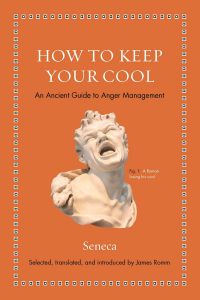

Posted By Dabney Hixson On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSeneca and James Romm, ed., trans.

How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management

Princeton University Press, 2019

Long before self-help books, pop-psychology gurus, TED talks, non-fiction political punditry, and “anger-management” classes, the ancients dispensed wisdom on a variety of topics, personal and societal. Princeton University Press is in the process of publishing a new series of these works, with pithy contemporary titles, in an abridged and accessible format under the imprint “Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers.” [2] Current works available include Aristotle on How to Innovate, Cicero on How to be a Friend, Horace on How to be Content, and Epictetus on How to be Free. Not only are the books printed in an easy-to-carry handbook format, with large enough print to make for comfortable reading, but they are attractive diglot editions, alternating pages between the original Greek or Latin and a contemporary English translation. Those who studied Latin or Greek in high school or college will find these editions perfect for easy reading of the English text, while occasionally checking the original.

My first dip into the series was Seneca’s How to Keep Your Cool, edited and translated by James Romm, professor of Classics at Bard College.

A brief introduction notes the substantial life of Seneca (4 BC-65 AD), a philosopher who moved in the upper echelon of first-century Roman society. He managed to survive the cruel and capricious reign of Caligula, was appointed by Claudius as tutor of a then thirteen-year-old future emperor Nero, and was eventually forced to commit suicide by his former student when he ascended to the throne. Seneca met his unjust fate (the order to end his life was motivated by Nero’s desire to inherit his substantial assets) with the same equanimity of spirit with which he had lived his life, derived from its grounding in Stoicism, though, according to Romm, he did not follow the Stoic path “in any orthodox way” (xii).

How to Keep Your Cool is an extract of about one-third of the original text of Seneca’s De Ira (Concerning Anger). It was composed in the form of an address to Novatus, Seneca’s older brother, a Roman politician, who later changed his name to Gallio when adopted by a wealthy patron of that name, and became the Roman ruler of Greece stationed in Corinth (and briefly mentioned in the New Testament book of Acts when St. Paul was arrested there; see Acts 18:12). The book is pithy, practical, and sapiential.

Seneca begins by noting that many of the wise have described anger as a “brief madness” [brevem insaniam] (4-5). [1] [3] He adds, “it resembles nothing so much as a collapsing building that breaks apart upon that which it crushes” (6-7). More than once, Seneca notes that, unlike other emotions, anger cannot be “hidden away” or “nurtured in secret,” given that it “announces itself and comes out in the face [in faciem exit]” (9). Anger is to be avoided, because it makes a man its slave. It is best to “repel instantly the first pricklings of anger” (19).

To those who object that a good man can become angry, especially if he should see some outrageous injustice (like the killing of his father or the rape of his mother), Seneca contends that it is never right to seek to punish wrongdoers out of anger. The mature man will carry out his duties “without fear or turmoil” (23), for there is “nothing great or noble in anger” (31).

[4]

[4]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [5]

Seneca’s discussion of anger is imminently pragmatic. One must first avoid whatever might make one fall into anger. If one fails and becomes angry, he must not do wrong because of it. The pragmatic angle leads him to offer guidance on child-rearing. Nothing produces anger in an adult more than “a soft and cloying upbringing” (41). Children, therefore, are never to be flattered or indulged.

Another key to avoiding anger is resisting the inclination to harp on the fact that one has been wronged. If one does have such a sense he must not act quickly or rashly. “One must take one’s time: a day reveals the truth [veritatem dies aperit]” (48-49). In this one might say we find the most quintessentially ideal response of Western man to dealing with his anger. Anger must be held back “pending judgement. A punishment that’s delayed can still be imposed, but once imposed, it can’t be withdrawn” (49). “Delay is the greatest remedy for anger” (67).

The wise man will not accept every evil report with naïve credulity, nor will he get annoyed “by tiny and very petty things [minimis sordidissimisque rebus]” (50-51). “The mind must be roughly treated so that it does not feel any blows except the heavy ones” (55). It is foolishness to get mad at inconsequential and especially inanimate things. “To get angry at things that are not alive is the mark of a madman. . .” (57).

In dealing with the foibles of our fellow human beings, we must remember that none of us are without guilt. Too often, “we hold the flaws of others before our eyes but turn our backs on our own” (65). A good look at ourselves will make us more temperate with others.

It is the distinction of a great man to overlook petty wrongs and injuries. The best revenge is often to determine that the fellow who has wronged you isn’t even “worth the trouble” (83). The “great and noble” person is often “like a huge wild animal” listening “without concern as the little hunting dogs yap” (83, 85). It does not pay to become angry with anyone, regardless of their standing: “To fight with an equal is a chancy affair; with a better, insane; with an inferior, tawdry” (91). When anger arises between two persons, “the better party is the one that steps backs first” (95).

Seneca suggests anger is a universal emotion. It affects all races. “It’s as powerful among Greeks, as among barbarians” (115). It also is unique in that it affects men en masse. Never did a crowd burn at once with lust or greed, but they often seethe collectively with anger.

Another strategy for avoiding anger is to spend one’s time with those who are “calmest, most easygoing, and least anxious, and depressed” (135). Similarly, we should run away from those who will stir up our anger! When an argument goes on too long and gets too heated, we should stop and walk away. We should also understand the times when we are most vulnerable to falling into anger. This often happens when we are physically exhausted, hungry, or thirsty. An old saying suggests “quarrels are sought by the weary” (145).

We should also try to understand the particular things which anger us. “People are not all wounded in the same spot” (151). Most wrongs should be overlooked. “You want to be less angry? Ask fewer questions” (151). Some wrongs “ought to be put off until later; others, laughed off; still others, forgiven” (151). Counter to most modern pop psychology, Seneca suggests it is often best to suppress expressions of anger: “Let’s obscure its signs and keep it shrouded and secret, as much as we can” (154).

Seneca closes his reflections by urging his readers to take up the Stoic practice at the close of each day of reviewing all of one’s actions and words: “When the daylight has faded from view. . . . I become an inspector and reexamine the course of my day, my deeds and words. I hide nothing from myself, I omit nothing” (191). Most importantly, one should always call to mind his mortality: “Nothing will aid us more than the contemplation of our mortality [Nec ulla res magis proderit quam cogatio mortalitatis].” (196-197). He ends with this hope: “Let no man hate my corpse on its bier” (203).

There is much to be learned from the ancients. For those who struggle with anger, Seneca’s book will prove a helpful tonic. Though Seneca notes the universality of anger among all races, his work also provides insight into the distinctive Western tradition that discourages spontaneous, angry outbursts, while promoting self-control, delay, getting the facts straight, fair judgment, and sober-self-reckoning. Perhaps this is why we look on with such dismay when non-Westerners are triggered by manipulative and deceptive media reports, lose their cool, riot in the streets, and self-defeatingly destroy their habitats.

They have had no Senecas to guide them.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Note

[1] [6] Romm often references the original book and chapter numbers from De Ira, but for this review, I will cite only the page numbers from How to Keep Your Cool.