Murder Maps: Agatha Christie’s Insular Imperialism

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled7,971 words

Twentieth Century Studios is threatening to release a remake of Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile (1937). And if Kenneth Branaugh’s previous outing as the Hercule Poirot character in 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express was anything to go by, best to avoid it. In an inspired bit of casting, the producers assigned a black man to play the role of Dr. Constantine. With any luck, Nile’s Colonel Race will be a flat-nosed Aborigine from the Outback. See the gorgeous 1974-1982 Poirot trilogy instead. Or, better yet, read the primary sources.

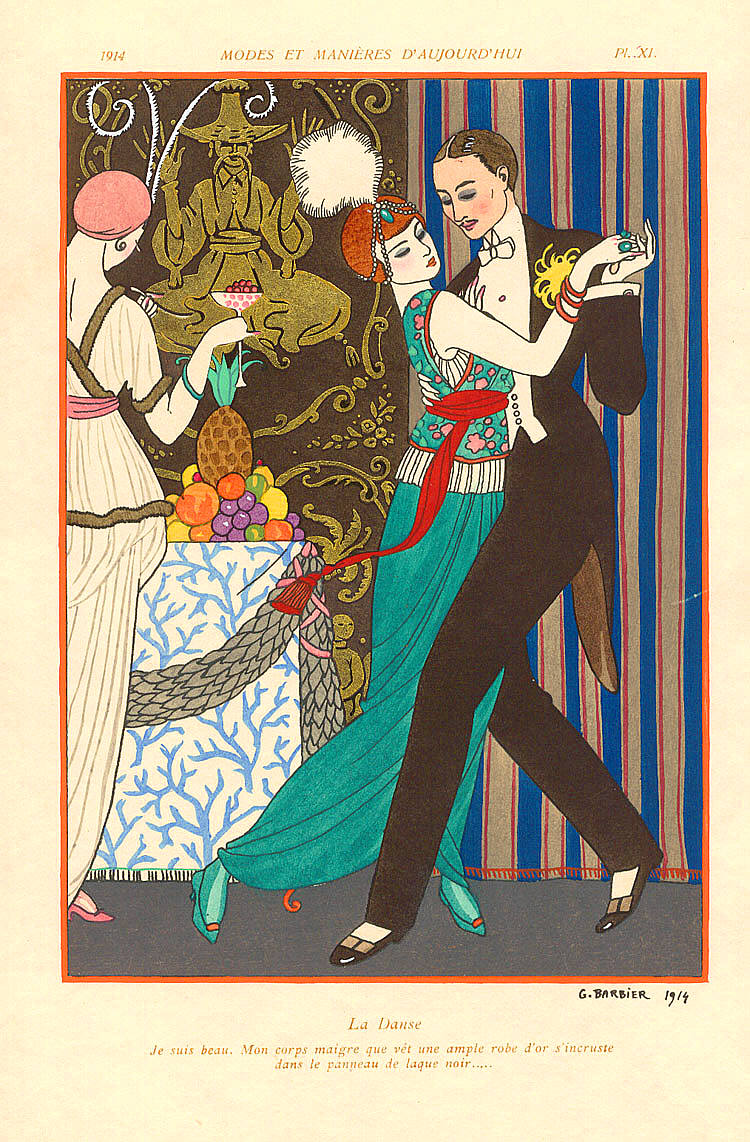

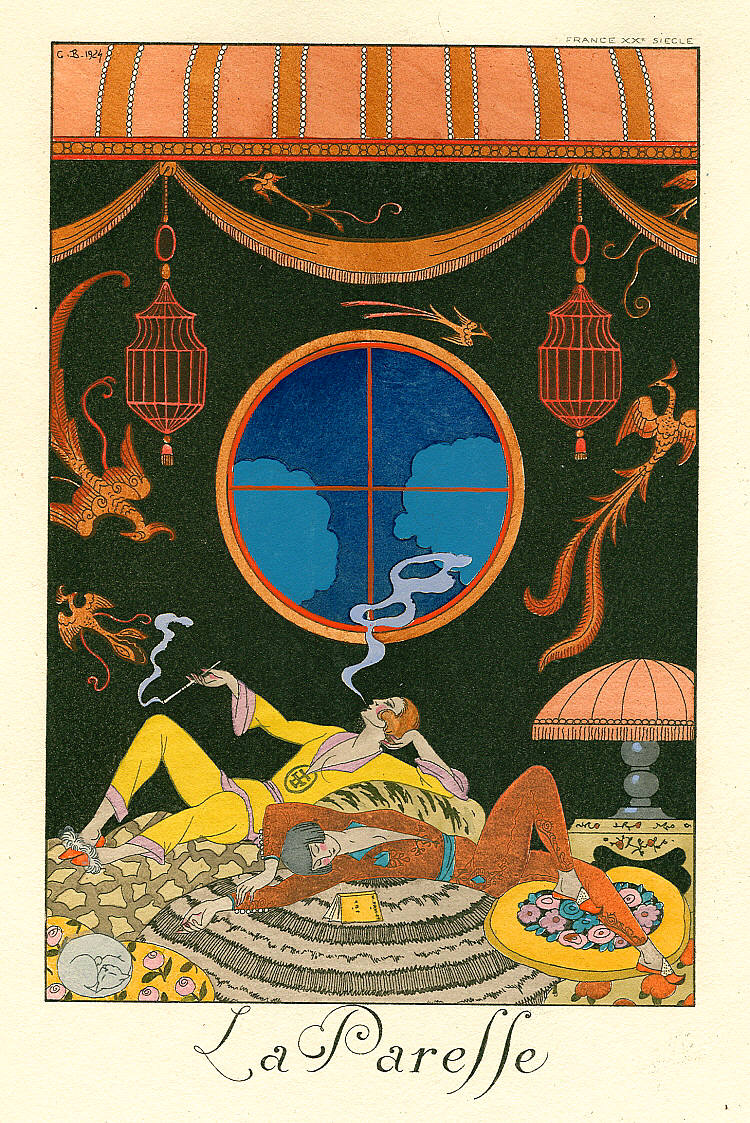

“Lit-ruh-chure” critics have long considered Christie’s novels lowbrow fare that generally lacked literary merit (mostly because people actually read her work). Yet, she remains the world’s bestselling author, going on forty-five years after her death (1976); only the Bible has given her any sort of competition. Why have her books endured so well? An obvious answer is the fondness we all seem to share for celebrity, murder, and mystery (an author rarely goes wrong when he decides to open his first chapter with a gruesome crime perpetrated against a young blonde). Another involves escapism. For all the aristocratic bad behavior depicted in her fiction, Christie’s stories have evoked a charmed era when Europeans dressed well, drank scotch and gin during afternoon luncheons, took long holidays in the Mediterranean — and above all took for granted white (and particularly British) dominion. Rule Britannia! It is indeed hard for whites (myself included) not to be seduced a little by the romance of St. George’s Empire, once breathtaking in its ambitious scope.

Agatha Christie (née Miller, 1890) was born to an American man and an English mother in the southwest of England. Just as many other fruitful endeavors have so begun, Christie’s success originated in an episode of sibling rivalry. Partly as a response to her sister Madge’s bet that she was incapable of writing a good detective story, Christie authored her debut novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1920. Her publishers would grow to expect at least three books from her per year, the third in time for the Christmas holidays — “a Christie for Christmas” became a common phrase in the Anglophone world. By the 1970s, she had published over seventy novels and fourteen collections of shorter stories that combined within their pages the old-world macabre and superstition with the modern fixation on realism and espionage. [1] [2] One of Christie’s hallmarks, for example, was a focus on the new “science” of psychology and on the way the mysteries explored the minds of her killers. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), for instance, the murderer himself narrated the story — a most striking (and chilling) example of this particular preoccupation with the criminal motive. She spoke through her most famous character, Monsieur Hercule Poirot, when the detective answered a matron’s question about where the Belgian’s fascination lay — “Do people interest you too, Monsieur Poirot? Or do you reserve your interest for potential criminals?” “Madame,” the funny little man replied, “that category would not leave many people outside it.’” [2] [3]

Of perhaps more interest to readers of Counter-Currents were her fervent, but quiet, Right-wing views. Christie’s books never trucked egalitarian slop, nor made feminist heroes of her female characters. In Christie’s world, nearly everyone was capable of vile deeds, regardless of age or sex. She wrote during both the twilight of the aristocracy and the British Empire, a sprawling hegemon that, at its apogee, flew its crossed colors over one-fifth of the globe’s landed territory. Yes, she wrote detective novels, but they were also romances dedicated to nonchalant European supremacy, to a confidence in Western values and institutions. Unconscious and unselfconscious mastery. Such colonial romanticism now irks our intelligentsia. Latter-day (Jewish) critics, meanwhile have accused her of antisemitism — a charge not simply leveled at the author due to her unabashed admiration of Charles Lindbergh. [3] [4]

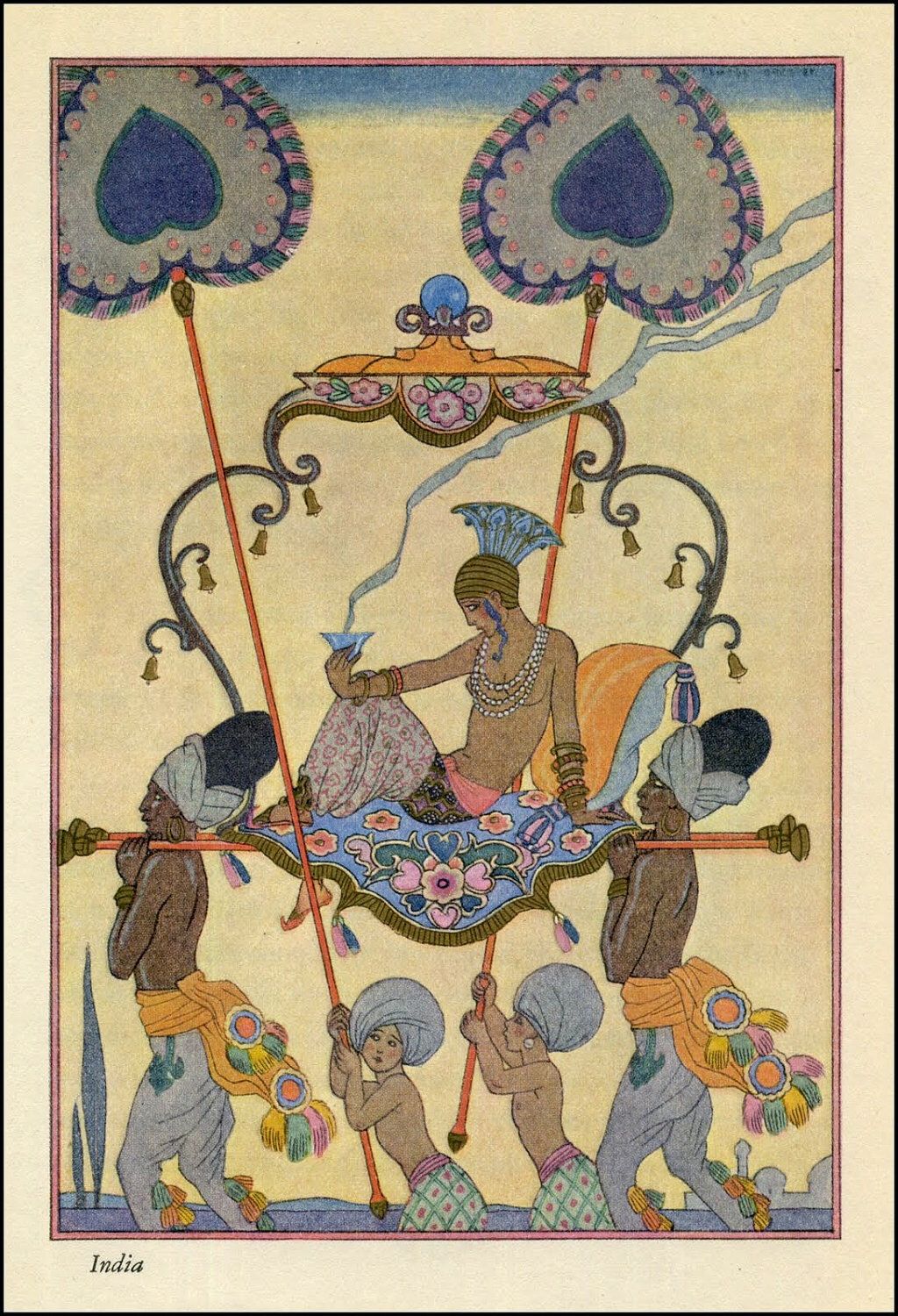

When she was a child in the 1890s, Britain was the undoubted center of the world: first in naval might, finance, and overseas possession. Following the American Revolution (1775-1783), the British Empire had appeared on the verge of decline. Instead of wallowing or retreating back into their small island fortress in order to “reassess,” or to “think things over,” Britishers devoted more energy to the Orient, particularly to that most lucrative and prized diamond adorning their imperial diadem — Hindoostan (India). But in general, the British were more concerned with maintaining their empire rather than expanding it during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This changed over the course of Queen Victoria’s long reign and culminated in “the Scramble for Africa” and various (mis)adventures in East Asia (The Opium Wars and “The Open Door” policy among them), all of which caused the Empire to suddenly swell to new and fantastic proportions. But by the interwar era (ca. 1920-1940), the British had once more returned to maintaining an empire that had bloated beyond prudence.

Christie herself developed a love affair with the Orient, and after her first husband left her for a younger woman, she remarried an archaeologist — a happy pairing that allowed her to indulge her passion for travel and ancient history. In a dedication to her new spouse, she addressed a few poetic lines:

Five thousand years ago

Is really, when I think of it,

The choicest Age I know.

And once you learn to scorn A.D.

And you have got the knack,

Then you could come and dig with me

And never wander back. [4] [5]

Of the wilds of Mesopotamia, she remarked, “The utter peace is wonderful. A great wave of happiness surges over me, and I realize how much I love this country, and how complete and satisfying this life is . . .” It was a place where Christie could mock “Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Turks and Yezidi devil-worshippers who worked on the excavations as freely as she could of Oxford scholars, of her husband and herself.” [5] [6] Simultaneously, and next to all this antiquity, were the modern innovations that condensed twentieth-century time and distance — and allowed for mass European tourism. Motor cars, trains, steamers, and aeroplanes all played indispensable roles in Christie’s Oriental murder mysteries. “Detection” and archaeology went hand-in-hand, after all, for each sifted through clues, and both investigated the dead.

But by the time of her own death in 1976, her native island kingdom was but a pale reflection of its former glory. It was suffering, too through an economic depression. Capital and the power to impose a “world order” had shifted west to America, and Britain’s empire consisted of ever-more loosening commonwealth ties to South Africa, Canada, and Australia, and ever-more loosely scattered territories, like the Falklands and Hong Kong. Christie often wrote of the Near East and “how much [she] love[d] that part of the world”; but in the 70s, the sort of vacationing in Egypt or Baghdad that she once enjoyed had become dangerous, and the Levantine cities she “loved” would soon become bombed-out shells of themselves. [6] [7] The famous mystery novelist was a witness to a profound tragedy that occurred (and is still occurring) to one of the most treasured parts of the globe — that ancient fulcrum of civilization. White advocates should take humbling note of the kinds of disasters that take but a lifetime to world-shatter and that will take much longer than our own lifetimes to remedy.

This will not be an essay about murder mysteries, but an exploration of that most interesting of British paradoxes through the medium of murder mysteries: the insular vs. the imperial dichotomy. Christie wrote so-called “locked door” detective fiction — stories that grouped (or trapped) characters together, whether on a boat, train, hotel resort, or deserted island — while at the same time setting her stories in the far-flung reaches of the British Empire; a cramped space in which literal movement proved difficult within an empire of seemingly boundless space (mystery-suspense and horror stories are most effective when characters cannot move without struggle). Her non-malicious satires poked fun at English hobbit-like provincialism and aversion to “foreigners,” even as their country was engaged in an imperialist project that meant to turn the world into an extension of the domesticated English garden (and when one stops to think for a moment, one realizes that these attitudes were but two manifestations of the same impulse). [7] [8]

NB: “Colonial” in this essay refers to whites of European ancestry born or having lived outside the West. In the greater Anglo-Saxon world, “colonial” was almost always a white person (joined by expressions such as “Anglo-Indian,” “white African,” “Boer,” etc.); when referring to nonwhites in the Empire, the British used terms like “Aborigine,” “colored,” “Hindoo,” “black,” “Sambo,” “tribesman,” “Mohammedan,” or “native.” Almost never were the locals or native porters seriously suspected of having committed the arch-crimes in Christie’s fiction. The schemes were too well-planned and ingeniously crafted for audiences to believe their simpler minds were capable of them. And what an anticlimax it would have made for Monsieur Poirot to have fingered a lowly colored footman for the murder of Lady Linette Ridgeway-Doyle! With a few exceptions, nonwhites filtered in and out of Christie’s stories to “set the mood,” as it were, to carry the luggage, and to part pretty English ladies from their coin in exchange for palm readings and colorful baubles from the bazaar. These were books whose Edwardian sensibilities appealed to interwar readers who found themselves pining for a past already lost to them. I am reminded of the last few lines of Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo:

I long sometimes for another glimpse of the “Beautiful Antonia” . . . going out serenely into the sunshine of the plaza with her upright carriage and her white head; a relic of the past disregarded by men awaiting impatiently the Dawns of other New Eras, the coming of more Revolutions. [8] [9]

God, help us all.

1. Colonials at Home: The Haunted Explorer Returns

One little Indian boy left all alone; He went and hanged himself and then there were none. [9] [11]

The threat of colonials “going native” had long been a dreaded bugaboo amongst metropole Britons. Stories like those told by Robert Hay seemed all too common. The expatriate Hay, a Scots artist, had moved to Egypt in 1824 with ambitions of “compiling a visual record of the East.” On his first full day in Cairo, he paid a visit to his fellow-countryman Henry Salt, where he saw one of Salt’s agents “skulking in a corner.” A filthy robe came up to the man’s chin, which “almost made [Hay] think it was a pig wrapped up in a burnoose, instead of an Englishman. Coffee was brought à la Turk.” [10] [12] Afterward, the young artist called on another Briton, James Burton, whose living arrangements were even worse. He witnessed “several of Mr. B’s [harem] ladies looking out the window, for [Burton] lived like the Turks in that respect” — that is, “shutting his womenfolk away from public view.” By 1826, Hay found the European section of Cairo “as alien as he had initially found the Arab” neighborhoods, “and disdained it.” [11] [13] But perhaps the “biggest ‘Oriental’ of them all was Edward William Lane,” known as “Mansoor” to his friends. For a time Hay lived with Lane and could attest to his friend’s outrageous behavior, including Lane’s purchasing and later marriage to a slave girl named Nafeeseh (at least “Mnsoor’s” intentions were honorable in the end). [12] [14]

The Sittaford Mystery (1931)

Indeed, maintaining an empire while keeping colonials, who were often guilty of having “gone native,” safely on the peripheries of white society was an anxious process for the British and one that propelled more than a few Christie plots and murder motives. Ironic, then, that so many of her cases involved claustrophobic conditions in which potential murderers and their victims were forced to live cheek by jowl. In the novel The Sittaford Mystery, the character (and victim) Captain Trevelyan was a retired naval officer who apparently hated women due to a romantic “jilting” he had once suffered as a young man overseas. He’d come back to England and rented the large Sittaford House to the Willetts, a mother and daughter pair fresh from South Africa themselves (“overfriendly, you know, like colonials are”). [13] [15] During a seance parlor game, the Willetts and several of their houseguests received a troubling message from the spirit board: “TREVELYAN DEAD.” Amidst a witching-hour blizzard, an expedition was then mounted to assess the welfare of the Captain — only for the sleuths to find his body slumped, lifeless, and surrounded by his most treasured possessions: “two pairs of skis, a pair of sculls [oars] mounted, ten or twelve hippopotamus tusks, rods and lines and various fishing tackle including a book of flies, a bag of golf clubs, a tennis racket, an elephant’s foot stuffed and mounted and a tiger skin.” [14] [16] The stuff of a former colonial adventurer. The past, it seemed, had finally caught up with Captain Trevelyan and had literally buried him under its weight. Snowed-in and with a murderer hiding in plain sight, the frivolity of the little party plummeted.

Though the truth would turn out to be more prosaic, the “red herrings” in Sittaford came under suspicion in part because of their past lives abroad. As one character put it of Trevelyan’s no-good nephew, “fellows that go off to the Colonies are usually bad hats. Their relations don’t like them and push them out there for that reason . . . [and] there you are. The bad hat comes back, short of money, visits wealthy uncle in the neighbourhood of Christmastime,” then presumably kills him for the inheritance. [15] [17] In the first half of the twentieth century, Britons were not as worried about colored Third Worlders invading their country as they were about their own racial kinsmen — the white colonials whose loose manners threatened their British insularity.

Cards on the Table (1936)

Major Despard, one of the prime suspects in Cards on the Table, might have resembled Trevelyan during the latter’s younger years. He was a tall, dashing aristocrat who’d made a living writing books about his explorations of the dark corners of the world — places like South America, East Africa, Sri Lanka, etc. He, too, scorned what in his view was an “effeminate” existence in favor of sport and safari. Oh, he admitted to liking England “for very short periods. To come back from the wilds to lighted rooms and women in lovely clothes, to dancing and good food and laughter — yes, [he] enjoy[ed] that — for a time. And then the insincerity of it all sicken[ed] [him], and [he] want[ed] to be off again.” [16] [18] While Sittaford depicted white colonials as having suffered enervation by way of the tropical climate, Despard held the opposite opinion: those of his countrymen who stayed at home were the degenerates, those who preferred the company of women — afraid of manly risk and loath to test their mettle against the elements.

Even though he was a straightforward man with a hatred for intrigue, Despard had skeletons hiding in his cupboard. Years before and during a South American jungle expedition, he’d trekked the Mosquito Coast with a researching botanist (Dr. Luxmore) and his wife. But the three Europeans soon caught a fever that drove the Doctor to the point of delirium. When the crazed man made as if to jump into the waters of a black, nighttime river, Despard seized his gun and aimed for Luxmore’s leg in order to prevent his friend’s suicidal plunge. Mistaking Despard’s purpose, Luxmore’s wife attempted to tackle the major, forcing the weapon up and the shot to tear through the Doctor’s back, killing him instantly (“foolish woman!”). Aware that such a story would have invited scurrilous speculation, Despard and Mrs. Luxmore agreed to keep the incident quiet and to tell all who asked that her husband had died of his illness. In a supremely white and self-assured way, Despard explained that though “the [native] bearers” who accompanied the trio “knew the truth . . . they were all devoted to [him] and [he] knew that what [he] said they’d swear to if need be. [They] buried poor old Luxmore and got back to civilization.” [17] [19] Despite precautions, the shooting in the wilderness would return to torment Despard “back in civilized” England.

Ten Little Indians, or And Then There Were None (1939)

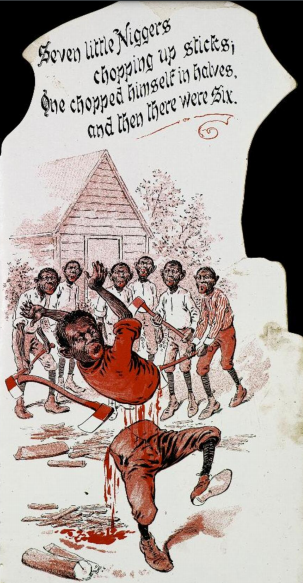

Christie’s 1939 novel Ten Little Indians (known, too, as Ten Little Niggers or And Then There Were None), also delved into the psychology of colonialism, particularly in the character of Philip Lombard, a “soldier of fortune.” Having received a job offer through a Jewish middleman and with the promise of a one-hundred guinea bounty, Lombard accepted the mysterious request with practiced insouciance, determined as he was not to give away the fact that he “was literally down to his last square meal.” Nonetheless, he could tell that the “Jew had not been deceived — that was the damnable part about Jews, you couldn’t deceive them about money — they knew!” [18] [20] Christie’s narrator described Lombard as feline and shrewd. His movements were lithe, “like a panther” on the hunt, his teeth “white and pointed,” his mind the coolest of the ten guests gathered on Indian Island (excepting, perhaps, Judge Wargrave). [19] [21]

[22]

[22]A plate from the rather grotesque Ten Little Niggers (1897), the minstrel rhyme that inspired Christie’s novel

Of all Christie’s longer pieces, Ten Little Indians was most like Gothic suspense — a nerve-wracking tale about a group of trapped and terrified people picked off, one by one, until there were none left alive. The enigmatic “Mr. and Mrs. Owen” had composed ten letters to ten people, including a doctor, a governess, a judge, a young hedon, a general, a mercenary (Lombard), two servants, an old maid, and a former policeman — inviting them all through carefully chosen enticements to join the Owenses on deserted Indian Island. These different people had one thing in common: each of them was responsible for the death of an innocent, and thus marked for punishment.

When accused via gramophone of killing “twenty-one men, members of an East African tribe” in February of 1932, Lombard was the sole man undisturbed at having his crimes aired before the company. In fact, he seemed proud. The “Story’s quite true!” he said, grinning. “I left ‘em! Matter of self-preservation. We were lost in the bush. I and a couple of other fellows took what food there was and cleared out.” General Macarthur, another servant of the Empire, and one more committed to duty and of preserving the veneer of imperial beneficence, asked sternly: “You abandoned your men — left them to starve?” Lombard shrugged: “’Not quite the act of a pukka sahib, I’m afraid. But self-preservation’s a man’s first duty. And natives don’t mind dying, you know. They don’t feel about it as Europeans do.’ Vera [the young governess] lifted her face from her hands. She said, staring at him: ‘You left them — to die?’” Lombard answered in the affirmative once more as “his amused eyes looked into her horrified” face. [20] [23] But try as general and governess might, they could not draw straight lines, nor solid moral boundaries that separated themselves from Lombard, for they too had sinned, and they too were physically stuck with the callous colonial soldier. Lombard was not bitter like Trevelyan, nor effeminately dissipated like Trevelyan’s Australian nephew, nor was he noble like explorer-hero Major Despard. Philip Lombard had come back from the colonies a hardened psychopath whose blood-stained hands bothered him not at all until they became the reason for his demise.

2. Britons Abroad: Backstabbing Aristocrats on Holiday

All three wore the air of superiority assumed by people who are already in a place when studying new arrivals. [21] [25]

By the 1930s, middle and upper-class Europeans could easily book a passage to the Orient, or to North Africa. The technological revolution in transportation afforded them steam liners, zeppelins, planes, railways, and automobiles with which to journey far; and each of these new modes of travel had become icons of modernity, of luxury and speed. But they could also be modes of violence and murder. Cars, trains, and airplanes could be terrifyingly efficient death machines that could entrap and then kill many men at a time. [22] [26] How could flesh and blood, bone and marrow confront 6,000 tons of steel and fire blasting along at forty or fifty kilometers per hour? World War I gave perhaps the most eloquent answer to this question. Agatha Christie’s fiction, too exploited the dual face of modern technology to great effect: how rich and beautiful Europeans enjoyed their outremer trips aboard the most fashionable rail and river liners — but also how these sleek new vessels were the perfect setting for murder. And in a foreign land with confusing languages, laws, and smells, with an unceasing heat that beat down and deranged the senses, any number of evils under a stronger, heathen sun were likely.

The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb (1924)

Besides full-length mystery novels, Christie wrote several collections of short stories, many of them featuring her Detective Poirot. In The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, Poirot’s sidekick Captain Hastings narrated the Belgian detective’s investigation of a curse unleashed by a vengeful pharaoh. Lord Carnarvon, Drs. Schneider and Ames, Sir John Willard, and a Mr. Bleibner of New York led the archaeological dig “not far from Cairo, [and] in the vicinity of the Pyramids of Gizeh,” when they “came unexpectedly on a series of funeral chambers. The greatest interest was aroused by their discovery, [for] the Tomb appeared to be that of King Men-her-Ra, one of those shadowy rulers of the Eighth Dynasty, when the Old Kingdom was falling to decay.” [23] [27] Almost immediately, members of the crew began dropping like flies, and the ancient burial ground began to resemble a modern-day morgue. Willard died “of heart failure,” Dr. Schneider of tetanus, Bleibner succumbed to septicemia, and Bleibner’s nephew — also part of the team — shot himself in New York. Alarmed when her son decided to journey to the tomb site himself in order to solve the mystery of his father’s death, Lady Willard hired Poirot and Hastings to help him. Though “You may think me a foolish, credulous woman . . . Monsieur Poirot, I am afraid,” she confessed. What if “the spirit of the dead King is not yet appeased?” [24] [28] Poirot agreed, and the two sleuths set off for the Sahara.

Hastings found that “the charm of Egypt laid hold of [him],” while Poirot complained incessantly of the sand, heat, and horseflies. Undaunted, Hastings pointed to the magnificent ruins: “Look at the Sphinx . . . Even I can feel the mystery and the charm it exhales.” But Poirot “looked at it discontentedly. ‘It has not the air happy,’ he declared. ‘How could it, half-buried in sand in that untidy fashion. Ah, this cursed sand! . . . It is true that they [the Sphinx], at least, are of a shape solid and geometrical, but their surface is of an unevenness most unpleasing. And the palm-trees, I like them not. Not even do they plant them in rows!’” [25] [29] Here then were the dual expressions of the imperial and insular white worldviews: one reveled in the exotic vastness of empire, while the other was only content in his native European habitat, or in those colonial environs comfortably Europeanized to suit his taste.

Once at the tomb, Poirot questioned the surviving Dr. Ames, “What [did] the native workmen think” of all the trouble? Did Ames believe in the curse? I suppose, said Dr. Ames, “that, where white folk lose their heads, natives aren’t going to be far behind. I’ll admit that they’re getting what you might call scared.” On cue, Lord Willard’s native servant Hassan appeared, begging Poirot to take his master’s son away from “the evil spirits.” [26] [30] In the end, of course, the killer was a flesh-and-blood man. Pairing the Gothic with the realist-Modernist was a common Christie device. Her characters experienced what at first seemed like supernatural events: seances, ghost sightings, and ancient curses — but by the end revealing them all as having a logical explanation. The murderer deliberately manipulated the Ouija Board; a wicked chemist devised a concoction that would release ghastly green vapors; doctors killed their patients under the guise of an old hex. As the detective observed, “Once get it firmly established that a series of deaths are supernatural . . . [and] you might almost stab a man in broad daylight, and it would still be put down to [a] curse, so strongly is the instinct of the supernatural implanted in the human race.” [27] [31] Which is perhaps another way of saying that whites who spend too much time among primitives become more primitive themselves.

Death on the Nile (1937)

Poirot returned to Egypt in Death on the Nile, a novel about a fatal love triangle between three young aristocrats: Lady Linette Ridgeway-Doyle, Simon Doyle, and Jacqueline de Bellefort, along with a motley group of European vacationers who accompanied them on a cruise up the Nile. Ever since Simon had abandoned his fiancée Jacqueline and married Jacqueline’s best friend Linette, the scorned lover had followed and harassed the honeymooning couple. Jackie had even threatened to kill them both — melodramatic gestures that Linette blamed on “the touch of Latin in her.” [28] [32]

Since “the boat was not full, most of the passengers had accommodation on the deck. The entire forward part of this deck was occupied by an observation saloon, all glass-enclosed, where the passengers could sit and watch the river unfold before them,” could watch the brown natives from a safe distance ashore. [29] [33] A welcome relief from the harassment they’d earlier experienced. As Poirot and a young Englishwoman named Rosalie were walking the promenade beside the river some hours before boarding,

Five watchful bead-sellers, two vendors of postcards, three sellers of plaster scarabs, a couple of donkey boys and some detached but hopeful infantile riff-raff [had] closed in upon them. “You want beads, sir? Very good, sir. Very cheap . . .” “Lady, you want scarab? Look — great queen — very lucky . . .” “You look, sir — real lapis. Very good, very cheap . . .” “You want ride donkey, sir? This very good donkey. This donkey Whiskey and Soda, sir . . .” Poirot made vague gestures to rid himself of this human cluster of flies, [while] Rosalie stalked through them like a sleep-walker. “It’s best to pretend to be deaf and blind,” she remarked. [30] [34]

A Mrs. Allerton too lamented the lack of peace whites enjoyed in Egypt and the impossibility of “‘[getting] rid of some of these awful children.’ A group of small black figures” had earlier “surrounded her, all grinning and posturing and holding out imploring hands as they lisped . . . hopefully . . . ‘they closed in on [Mrs. Allerton] little by little’” until she yelled “Imshi” brandishing her sunshade at them. They “scattered for a minute or two. And then they came back and stared and stared, and their eyes were simply disgusting, and so were their noses . . . I don’t believe I really like children – not unless they’re more or less washed and have the rudiments of manners.” [31] [35] In other words, Mrs. Allerton only found white children tolerable. Even though murder quickly turned the cruise ship into a coffin, it was at least devoid of nonwhite pests (save for the mostly invisible serving staff). Readers got the distinct impression that Poirot, Rosalie, Mrs. Allerton, et al. preferred the white nightmare aboard the SS Death Trap to spending another minute with the colored irritants on land.

Murder in Mesopatamia (1935)

As one character put it, “it’s been nice to see a bit of the world — though England for me every time, thank you. The dirt and the mess in Baghdad you wouldn’t believe — and not romantic at all like you’d think from the Arabian Nights!” While “it’s pretty just on the river . . . the town [Baghdad] itself is just awful — and no proper shops at all. Major Kelsey took me through the bazaars, and of course there’s no denying they’re quaint — but just a lot of rubbish and hammering away at copper pans till they make your head ache . . .” Venturing out from the old city and into the desert required riding in a “station wagon” that made the trip an uncomfortable, “jolting” experience. Echoing Poirot’s sentiments, Nurse Amy Leatheran “wonder[ed] [that] the whole contraption didn’t fall to pieces! And nothing like a road — just a sort of track all ruts and holes. Glorious East indeed!” the young nurse exclaimed sarcastically. “When I thought of our splendid arterial roads in England it made me quite homesick.” From a distance, Baghdad appeared “white and fairy-like with minarets. It was a bit different, though, when one had crossed the bridge and came right into it. Such a smell and everything ramshackle and tumbledown, and mud and mess everywhere.” [32] [37] Like many Britons abroad, Amy took pride and a certain satisfaction in the Levantine lands under British mandate, but she couldn’t help wishing that the colonies had the conveniences of England. She desired a covered car with shock absorbers and windows that protected her from and mitigated the noisome Oriental reality. The European “white and fairy-like” visions of the East had given way to the refuse of brown “mud and mess.”

Like “Egyptian Tomb,” Murder in Mesopotamia was a Poirot case set amidst an archaeological dig. Dr. Leidner presided over these Assyrian ruins, and had also been tending to his sick wife Louise shortly before her unexplained murder. In life, Louise had possessed a “Scandinavian fairness that you don’t often see,” but “her face was rather haggard, and there was some grey hair mingled with the fairness.” [33] [38] The Orient, it seemed, agreed with Mrs. Leidner as much as it did poor Amy Leatheran. Meanwhile, a con-man posing as a French monk was stealing ancient artifacts and replacing them with plaster copies; Mr. Mercado, another archaeologist and a long-time colleague of Dr. Leidner, had since degenerated into a nervous drug addict. Strange hauntings during the night plagued the team, and the native workmen grew restive. That an insular group of affluent Europeans such as this one assumed that their misbehavior would remain an internal matter, that clear lines separating us from them existed, that colonized peoples would not notice, nor infringe upon their white bubble — that was perhaps the most striking feature of Christie’s “colonial novels.” And readers could be forgiven for seeing a metaphor in these “locked door” mysteries, for “the locked door” did not lock from the inside. Though Europeans imagined that they kept the “barbarians” at bay, that their intra-racial troubles were theirs alone, the twentieth century would dash those fantasies into the dust.

3. Strangers at Home: Unnatural Aliens Poison the Mind

“The gift — curse — call it what you like . . . Look hard at that hollow in the rocks. Don’t think of anything, just look . . .” It must have been my imagination. Just for a second I saw it full of blood! [34] [39]

Unfortunately, the mass transit systems of modernity that allowed Europeans quick access to their empires and vacationers, their easy journeys to tropical islands, were not one-way avenues. Nonwhites from around the globe have used Western technology and Western squishy-headed ideas of universal fair-play to settle in once-white countries. Though this problem may not have seemed acute in the interwar and immediate postwar years, authors like Christie were not blind to the shifting turn of events. For all the romanticism attached to the “Lion’s Share,” to the empire snatched, struggled over, and built by the Victorian Britons with their ironclad confidence in British values, it meant multicultural confusion and ultimate disillusion when the Empire itself dissolved. Since the world had once been beneath the cross of St. Andrew — had been, for a few decades, Her Majesty’s royal preserve — now those thoroughly un-British colored people from Trinidad and Tobago, New Guinea, and Botswana had suddenly become British subjects. Their empire had gone, but the responsibility remained. Only now, whites could no longer escape the Arab “bead-sellers,” buzzing “black children,” and “human clusters of flies” that swarmed ashore, their hands still outstretched and their accented voices crying aggressively, “mine!” and for “more!”

The Gipsy (1933)

Recall that Christie almost always “rescued” rationality from the irrational. With few exceptions, “supernatural” happenings had hidden behind them perfectly natural reasons. Her short story “The Gipsy” was one of those rare exceptions. While not about nonwhites or ethnic gypsies per se, the presence of this large population of nonwhite nomads wandering Europe haunted the story with disquiet. The dark tales that follow were those of disasters that befell Christie’s characters when “diversity” darkened the doorstep of their once-sequestered island nation. [35] [40]

It began when “Dickie” Carpenter complained to the narrator about his “strange aversion to gipsies.” Indeed, “It all started with a dream [Dickie] had when [he] was a [child]. Not a nightmare exactly . . . the gipsy . . . would just come into any old dream — even a good dream . . . and then [he’d] feel that if [he] looked up, she’d be there, standing as she always stood, watching [him] . . . With sad eyes . . . as though she understood something that [he] didn’t.” Dickie was at a loss to “explain why it rattled [him] so — but it did! . . . [he] used to wake up howling with terror, and [his] old nurse used to say: ‘There! Master Dickie’s had one of his gipsy dreams again!’” [36] [41] And some time ago, he’d met a woman near the edge of a brook, wearing a red gypsy scarf. He felt that same dread. She’d warned him, “I shouldn’t go that way if I were you.” Startled, the young man crossed to the bridge and over the water — but it collapsed beneath his feet, and Dickie nearly drowned. And just a few days ago, the same sort of woman in scarlet had advised him not to get an operation on his leg, an appendage that had bothered him since its injury in the Great War. Who, he asked, was the “dark” woman in red? Oh, his female companion said, “you mean Alistair Haworth? She’s got a red scarf. But she’s fair. Very fair.” And “So she was,” Dickey admitted, for “Her hair was a lovely pale shining yellow. Yet I could have sworn positively [that] she was dark. Queer what tricks one’s eyes play on [a person] . . .” [37] [42]

Predictably, Dickie died on the operating table.

Now himself disturbed, the narrator sought out the “red-scarfed gipsy,” the woman named Alistair Haworth, and was shocked at her Scandinavian beauty, for “In spite of Dickie’s description” the narrator had “imagined her gipsy dark” as well. And he suddenly remembered Dickie’s words and the peculiar tone of them. “You see, she’s very beautiful . . .” Dickie had told him. “Perfect unquestionable beauty is rare, and perfect unquestionable beauty was what Alistair Haworth possessed.” [38] [43] An unnatural, even monstrous allure. Gathering his courage, the narrator approached her. Mrs. Haworth proceeded to confess to him the curse from which she suffered — a second Sight that presaged a person’s fate. Pointing to a river, she asked if the narrator could see blood trickling down the rocks like she could; the area, she explained, was once the site of human sacrifice. She’d married her unattractive husband, she went on, not out of love, but in order to save him from an evil event that she’d sensed would one day destroy him.

As Mrs. Haworth and the narrator parted ways, she foretold they would not meet again. Ironically, the “evil event” that befell Alistair’s husband was her own death, a destiny she could not prevent. Truly shaken, the narrator turned from the demi-monde, “that other world” of gypsies. Instead, he embraced his fiancée with her “honest brown” eyes and clung to her “like a man awakening from a dream, a warm rush of glad reality swept over him.” [39] [44] The horror lay not only in Mrs. Haworth’s premonitions, but in the unnatural fact that a dark gypsy lay hidden inside the outer shell of an innocent, beautiful white woman with flaxen hair and grey eyes. What sort of place was this where darkness had sapped even the palest of all English roses?

The Lost Mine (1924)

Even in Christie’s day, London’s East End housed a teeming immigrant neighborhood known as “Chinatown,” and at intervals, Poirot found it necessary to venture into those seedy shanties and alleyways of cutthroats and thieves. Toward the beginning of “The Lost Mine,” a Chinese professional named Wu-Ling had booked himself a hotel in preparation for a business deal: that of selling his Burmese mine shares to several English investors. But the Chinaman vanished on the morning of the sale — along with the required papers. Hired to solve the mystery of Wu-Ling’s disappearance, Poirot and an interested banker disguised themselves and infiltrated “a certain unsavoury dwelling‐place in Limehouse, right in the heart of Chinatown. The place in question was more or less well known as an opium‐den of the lowest description.” There, they ate peculiar dishes in “a low little room with many Chinese in it.” In some gastrointestinal distress, Poirot exclaimed, “‘Ah, mon Dieu, mon estomac!’ . . . before continuing [on]. ‘Then there came the proprietor, a Chinaman with a face of evil smiles.’ ‘You gentlemen no likee food here,’ he said. ‘You come for what you likee better. Piecee pipe, eh?’ The Chinaman took them “through a door and to a cellar and through [another] trapdoor, and [then] down some steps and up again into a room all full of divans and cushions . . . [they] lay down and a Chinese boy took off [their] boots.” More serving men “brought the opium‐pipes and cooked the opium pills.” The two Europeans “pretended to smoke and then to sleep and dream.” [40] [46]

During this ruse, the white men overheard that Wu-Ling had not simply been abducted, but done away with. To “the Oriental mind, it was infinitely simpler to kill Wu Ling [and then] to throw his body into the river.” [41] [47] The Chinese criminal gangs had their own methods and felt themselves beyond the reach of Anglo-Saxon law. When accused of prostitution, drug-peddling, or murder, their impassive (and often indistinguishable) faces closed off, and they “denied everything with [typical] Oriental stolidity.” [42] [48]

Cards on the Table, continued (1936)

And now we return where we began: to Cards on the Table with its psychological game of bluff and bet manipulated by a wicked puppeteer. Mr. Shaitana was both victim and perpetrator in Cards on the Table, but whether he “was an Argentine, or a Portuguese, or a Greek, or some other nationality rightly despised by the insular Briton, nobody knew.” [43] [49] His name in Hindi was a cognate of “Satan,” his soft, “purring” voice, his tall silhouette, and bizarre attire produced a “deliberate Mephistophelian effect.” [44] [50] Indeed, “every healthy Englishman who saw him longed earnestly and fervently to kick him! They said, with a singular lack of originality, ‘There’s that damned Dago, Shaitana!’” [45] [51] In truth, Shaitana had relatives in Syria, but he loved the impact that his enigmatic origins had on the British, and so he mentioned little about his own past.

Instead, he’d purchased a luxurious home in England and set about adding to his collections of rare objects and people — a man not unlike the infamous Tipu Sultan of eighteenth-century Mysore. [46] [52] Indeed, Shaitana reminded his dinner guests of just such an eastern despot, for “There [was] always something a little frightening about him . . . [one] never [knew] what would strike him as amusing. It might . . . [have been] something cruel . . . something Oriental!” [47] [53] It apparently amused him to invite to dine and thus to bring into his private “collection” at once four sleuths (including Poirot) and four murderers who had gotten away with their crimes. In “the dimness, at the head of the table, Mr Shaitana looked more than ever diabolical.” The candlelight “threw a red shade from the wine on to his face with its stiff, waxed ends and . . . fantastic eyebrows.” [48] [54]

Shaitana proceeded to engage in a cruel mind game that upended the guests’ quiet English lives and opened skeleton-filled closets long thought closed. By the time the “game” ended, several members of the dinner party and Shaitana himself were dead. As one member of the ill-fated group, Major Despard considered his host the sort “who needed beating badly . . . He was too well dressed — he wore his hair too long — and he smelt of scent . . . He got a thrill out of seeing people quail and flinch . . . it made him feel less of a louse and more of a man. And it [was] a very effective pose with women . . . the man was an ape!” [49] [55] The major enjoyed gallivanting in the colonial wilds and appreciated the deference natives there paid to a man like himself: an intrepid and commanding British explorer of means. But when a “louse” like Shaitana, who preyed on the weaknesses of white women, settled in the major’s own native land and began to meddle in the business of Europeans — even setting them against one another — that was disgusting. Despard knew instinctively that Shaitana had crossed a line that white men needed to vigilantly guard with their lives. The Syrian fiend could rot in the same hell with which he affected so much familiarity! He belonged nowhere near the Berkshire Downs.

Conclusion

Following the World Wars, those murderous intra-racial feuds fought for all the nonwhite world to watch and wonder at their European masters’ foolishness, Britons began to realize that maintaining an old-fashioned empire had become too expensive and embarrassing. The easy self-confidence had gone with the guns of August. John Maynard Keynes of the British Royal Treasury foresaw a “financial Dunkirk” ahead and warned that “We cannot police half the world at our own expense when we have already gone in to pawn the other half.” [50] [56] Indeed, both the imperial Exchequer and the imperial moral philosophy that helped keep it afloat were bankrupt. But the idea of a Britain without an empire, the thought that she might become “a sort of poor man’s Sweden” was equally unbearable. [51] [57] Even so, international pressure from nonwhite independence/terrorist movements and from the United States, whose “founding principles” were anti-colonial, wore down their reluctance. And just as the British dissolved much of their empire, many of them sought admittance into Europe — a continent that for much of their history Britons had coolly held at arm’s length from across their Channel of Solitude — an ironic turn marking the end of British supremacy. Should it surprise anyone that their insularity, their strong borders, crumbled at the very moment that their world-making imperialism came tumbling down? Not if one understands that these two policies were not opposites, but one and the same Anglo-Saxon attitude.

And what, further, has become of Agatha Christie’s Tartary? The “great expectations” for the Middle East came to naught. As the British Chief Secretary of Palestine assessed: the state “is full of uncertainties . . . Jerusalem the golden; or, as Josephus put it, a golden bowl full of scorpions.” [52] [58] It is painful to read Christie’s 1944 paeon to this bygone era’s edge along the Mediterannean. Her memoir of the East discussed no elaborately-plotted mystery, but of a kind of murder, it surely did. From the dingy dugouts of wartime Britain she wrote, “I love that gentle fertile country and its simple people, who know how to laugh and how to enjoy life; who are idle and gay, and who have dignity, good manners, and a great sense of humour, and to whom death is not terrible. God willing, I shall go there again, and the things that I love shall not have perished from this earth . . ” [53] [59] For indeed, they have “perished,” along with countless other things Westerners once took for granted, imagining they would always be masters of the earth, that there would always be a boat at their command, waiting to take them up the old river, that the train at Istanbul would always arrive on time.

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [60] See Billie Melman, “Murder in Mesopotamia: Antiquity and Genres of Modernity in the Popular Crime Novel,” in Empires of Antiquities: Modernity and the Rediscovery of the Ancient Near East, 1914–1950 (Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 191-215.

[2] [61] Agatha Christie, Death on the Nile (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 110.

[3] [62] Then again, almost everyone would have qualified before ca. 1950.

[4] [63] Agatha Christie, Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 6.

[5] [64] Ibid., 12.

[6] [65] Roberta Mullini, “ ‘How Much I Have Loved That Part of the World’: Agatha Christie and the Orient” in Linguæ & rivista di lingue e moderne, vol. 1 (2006), pp. 25-33, 25.

[7] [66] As a foreigner from the Continent, Poirot himself was often the object of British side-eyed suspicion. Flippant slurs (“dago,” most commonly) disparaging other white Europeans abounded in Christie’s work.

[8] [67] Joseph Conrad, Nostromo (Oxford University Press, 2007), 411.

[9] [68] Agatha Christie, Ten Little Indians (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 37.

[10] [69] Diary of Robert Hay, November 23, 1824, Bodleian Library: Hay Papers, Add. MSS 31,054, folios 81-83.

[11] [70] Diary of Robert Hay, November 23, 1824, BL: Hay Papers, Add. MSS 31,054, f. 115.

[12] [71] Maya Jasanoff, Edge of Empire: Lives, Culture, and Conquest in the East, 1750-1850 (New York: Vintage, 2005), 291.

[13] [72] Agatha Christie, The Sittaford Mystery (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 51.

[14] [73] Ibid., 40.

[15] [74] Ibid., 198.

[16] [75] Agatha Christie, Cards on the Table (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 61.

[17] [76] Ibid., 191.

[18] [77] Ten Little Indians, 9. The Jew’s name was Isaac Morris, a “shady little creature [and] amongst other things he was a dope pedlar.”

[19] [78] Ibid., 43, 56.

[20] [79] Ibid., 50, 70.

[21] [80] Death on the Nile, 58.

[22] [81] See Melman’s “Murder in Mesopatamia,” 192.

[23] [82] Agatha Christie, “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” in The Last Seance: Tales of the Supernatural (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 50.

[24] [83] Ibid., 52.

[25] [84] Ibid., 55-56

[26] [85] Ibid., 61.

[27] [86] Ibid., 64.

[28] [87] Death on the Nile, 85.

[29] [88] Ibid., 118-119.

[30] [89] Ibid., 56.

[31] [90] Ibid., 109.

[32] [91] Agatha Christie, Murder in Mesopatamia (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 9-10.

[33] [92] Ibid., 34.

[34] [93] Agatha Christie, “The Gipsy” in The Last Seance: Tales of the Supernatural (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 109.

[35] [94] See Tony Norman, “Gothic Stagings: Surfaces and Subtexts in the Popular Modernism of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot Series” in Gothic Studies, 18, no.1 (May 2016) pp. 85-99.

[36] [95] “The Gipsy,” 104.

[37] [96] Ibid., 104-105.

[38] [97] Ibid., 108.

[39] [98] Ibid., 113.

[40] [99] Agatha Christie, “The Lost Mine” in Poirot’s Early Cases (New York: Harper Collins, 2012), 95, 97.

[41] [100] Ibid., 98.

[42] [101] Ibid., 95.

[43] [102] Cards on the Table, 12.

[44] [103] Ibid., 10, 11.

[45] [104] Ibid., 11.

[46] [105] Tipu Sultan (1750-1799), also known as the “Tiger of Mysore,” was a regional prince in southern India — and one who constantly frustrated the British in their colonial designs. When the East India Company’s imperial army finally killed him during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799, they found among his possessions rooms filled with Western art, books, scientific devices, and other trinkets from Europe. Tipu Sultan had an apparent fetish for collecting white cultural items. Turnabout is fair play, I suppose.

[47] [106] Cards on the Table, 21.

[48] [107] Ibid., 24.

[49] [108] Ibid., 138.

[50] [109] Memorandum by John Maynard Keynes, Top Secret, 28 September 1944, Treasury, 160/1375, folio 17942/101/5.

[51] [110] Charles Johnston to Colonial Office, Secret, 16 July 1963, folio 371/168630.

[52] [111] Phyllis Lassner, Colonial Strangers: Women Writing the End of the British Empire (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 19.

[53] [112] Come, Tell Me How You Live, 218.

Further Reading on the Empire

The Oxford History of the British Empire, Vol. IV: The Twentieth Century, Judith M. Brown and William Roger Louis, eds. (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Fictions of Empire: Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King, & Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Beach of Falesá, John Kucich, ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003).

The Cambridge Illustrated History: British Empire, P. J. Marshall, ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Robert Johnson, Histories and Controversies: British Imperialism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

David Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).

David Cannadine, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1994).

Bernard Porter, The Lion’s Share: A Short History of British Imperialism, 1850-2004, 4th ed. (London: Longman, 2004).

Piers Brendon, The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781-1997 (New York: Vintage, 2010).