Mihai Eminescu: Romania’s Morning Star

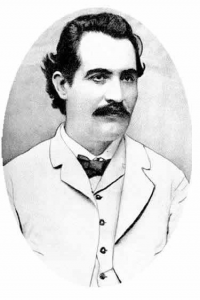

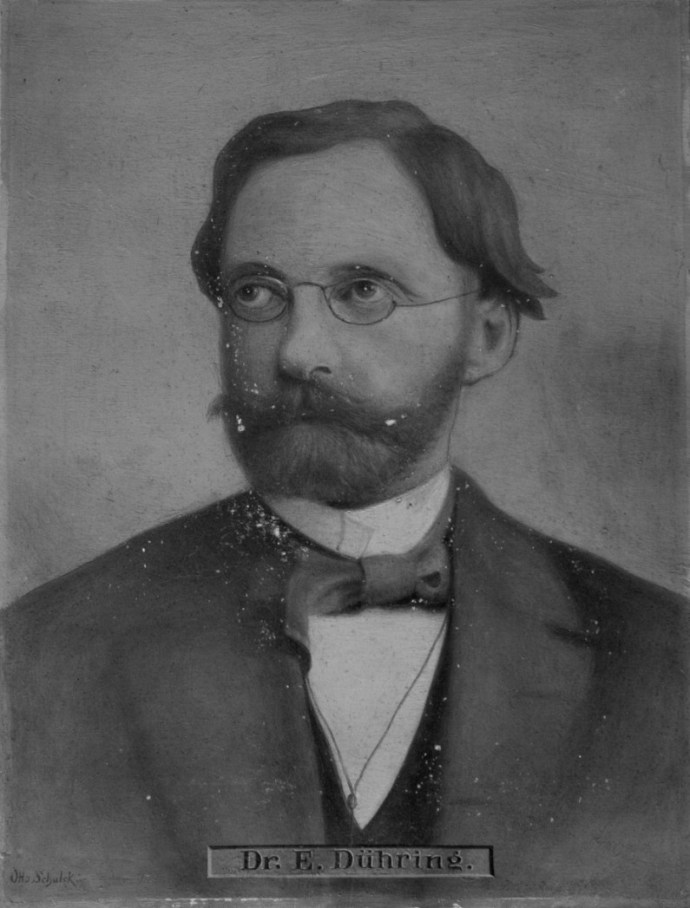

Posted By Amory Stern On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOf peasant ancestry on his father’s side and boasting aristocratic (boyar) maternal roots, the Romanian poet, prose writer, and editorialist Mihai Eminescu (1850-1889) had not put his modest inherited wealth to waste. Educated in the German language since childhood, Eminescu was culturally — if not always geopolitically — an enthusiastic Germanophile. As a young man, he had studied in Vienna and in Bismarck’s Prussia, where he had learned Sanskrit and immersed himself in Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophy. He had also been a student of Eugen Dühring.

Eminescu had intellectual precedents in his own country, but he often made radical departures from them. His ideas were influenced by a leading conservative Romanian cultural circle called Junimea, which originally reflected the interests of the old Moldavian boyar class that had been displaced by the liberal bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century. However, there are significant differences between Eminescu’s philosophy and Junimism.

“The Junimists,” notes Hungarian-Jewish historian Nicholas Nagy-Talavera, “wanted literature to be separated from politics; to remain l’art pour l’art, with no social content desirable.” Eminescu rejected this doctrine, and some of his poems are explicitly political. Nagy-Talavera also points out that Eminescu was “less of an elitist” than the prototypical Junimist, and that “Junimism was opposed to anti-Semitism, considering it to be a barbarous affront to human intelligence.” [1] [2] With the latter opinion, Eminescu disagreed.

According to William O. Oldson’s A Providential Anti-Semitism: Nationalism and Polity in Nineteenth Century Romania, Eminescu “stood out as the most eloquent spokesman of the radical anti-Semites.” Eminescu viewed Romania’s relatively recent Jewish immigrant population, by and large, as inherently unpatriotic. He has been described as a fierce opponent of civil equality for the Jews, arguing, as summarized by Oldson, that “they presently constituted a danger to the Romanian nationality, when they did not possess equality of rights. They would be so much the more a peril once naturalized to any extent.” [2] [3]

Additionally, Eminescu was hostile to liberalism. He did not consider Republican France a good political model for Romania to emulate, and he regarded the United States as an even worse one. Nagy-Talavera summarizes Eminescu’s worldview thus:

Eminescu’s goal — he defines it as his “supreme law” — was the preservation of his country and its ethnic identity. . . Consequently, the national interest must determine every political, educational, and cultural decision. Thus, in Eminescu’s eyes, what he called “American liberalism” (or Western humanitarian values) might imperil the uniqueness of the Romanian ethnic character, and should therefore be rejected. . . He rejected the incomplete and superficial Westernization of 1848. Eminescu recognized only two positive classes in Romania: the nobility, and, above all, the peasantry. Any development must be based on the peasant, and it must be an organic one. . . Eminescu was closer to the peasants than to the boyars. [3] [4]

Eminescu was not one to follow trends. Unreceptive to popular French Decadent-influenced styles, he instead chose to model his verse after the golden age of German Romantic poetry. Whereas most other 19th-century Romanian literature was lighthearted, his was deep and often grim. This independent-mindedness also applied to his essays. At a time when other critics of capitalism supported the fledgling socialist movements, Eminescu rejected the latter on philosophical grounds — even as his pro-peasant and pro-worker worldview rendered him lonely on the conservative Right.

Eminescu’s religious beliefs are somewhat enigmatic. His editorials champion the Romanian Orthodox Church as an honorable national institution, and his friend Ion Creangă was a deacon. On the other hand, Eminescu believed the Phanariot Greeks of Constantinople enjoyed undue and pernicious influence over the Orthodox Church. In the early 18th century, up until the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, the Phanariots had been appointed by the Ottoman Turks to rule the Romanian principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia. They had dismantled and disarmed the free peasantries of those principalities, and in many ways ruined their economies. Furthermore, they controlled the Ecumenical Patriarchate of the Orthodox Church in Eminescu’s time, as they still do today. Eminescu regarded the Phanariots as enemy number one, even more than Jewry. Torn between his respect for the Romanian Orthodox Church and his hatred of the Phanar, Eminescu included anti-clerical and overtly non-Christian themes in his poetry, even as he often defended the Church from its liberal critics.

Eminescu was killed by medical malpractice in 1889. He was only 39 years old. Foul play has been widely theorized.

Poetry is categorically difficult to translate, and Eminescu’s work often resists translation. Nevertheless, several English-translated collections of his work exist in print. Others can only be found online.

Translator Adrian George Sahlean’s volume, Mihai Eminescu: The Legend of the Evening Star & Selected Poems & Prose, is an excellent introduction to Eminescu’s philosophically driven poems. Editor A.K. Brackob’s Poems and Prose of Mihai Eminescu is a larger volume, closer to comprehensive than Sahlean’s. This writer, Amory Stern, has edited and published a modest but inexpensive collection of some of Eminescu’s editorials, entitled Old Icons, New Icons. Out of print, but easy to find on the internet, are the poetry translations of Corneliu M. Popescu.

Each of these collections has its strengths and disadvantages. Old Icons, New Icons is a good introduction to Eminescu’s political and economic thought, but it is only a sample of his extensive body of essays and editorials. Sahlean’s volume contains some of the best Eminescu translations in existence, but it leaves out all of Eminescu’s politically charged and virulently politically incorrect poems. Brackob’s collection is not held back by such censorship, and includes Eminescu’s political poems, but the translations are of uneven quality overall. Popescu’s translations work quite well as poetry, but are not noted for their accuracy.

Philosophy of Time and Death

Eminescu’s poems often explore the concept of the eternal return, independently of Nietzsche but with the same heavy influence of Schopenhauer and Eugen Dühring. According to Rudolf Steiner, Nietzsche’s idea of the eternal recurrence was heavily influenced by Dühring’s philosophy of science. That argument is lent credibility by the work of Dühring’s student Eminescu, who had never heard of the then-obscure Nietzsche, but who propounded at least as developed a doctrine of circular time. This can be best seen in Sahlean’s translation of Eminescu’s inspirational poem “Glossa,” for example in the opening verse:

Time goes by, time comes along,

All is old and all is new;

What is right and what is wrong

You must think and ask of you;

Have no hope and have no fear,

Rising waves can never hold;

If they urge you, if they cheer,

You remain aloof and cold. [4] [5]

“Glossa,” as we see, concerns Eminescu’s rejection of the progressive idea of time in favor of the eternal return:

Past and future, ever blending,

Are the twin sides of one page:

New start will begin with ending

When you know to learn with age.

All that was or be tomorrow

We have in the present, too —

But what’s vain and futile sorrow

You must think and ask of you.

For the living cannot sever

From the means we’ve always had;

Now, as years ago, and ever,

Men are happy or are sad:

Other masks, same play repeated —

Diff’rent tongues, same words to hear;

Of your dreams so often cheated,

Have no hope and have no fear. [5] [6]

Note Eminescu’s advocacy of an ethos similar to that of the ancient Stoics — or Nietzsche’s Amor Fati — in the face of eternally recurring time. This concept had an important precursor in Schopenhauer, who associated it with death. Schopenhauer had written: “After your death you will be what you were before your birth.” [6] [7] In other words, he argues, death returns us to a realm outside of time and space, which are only products of temporal cognition. Explains Schopenhauer:

The present has two halves, one objective and one subjective. Only the objective has the intuition of time as its form and so it rolls on undeterred; the subjective stands firm and is therefore always the same. From this arise our vivid recollection of the remote past and the consciousness of our immortality, in spite of our knowledge of the transience of our existence. [7] [8]

Schopenhauer continues:

As a result of all this, life can indeed be regarded as a dream, and death as the awakening. But then personality, the individual, belongs to dreaming and not to waking consciousness, which is why death presents itself to the latter as annihilation. In any case, however, from this point of view it is not to be regarded as the transition to a state that is entirely new and foreign to us, but on the contrary only as the retreat to one that is originally ours, of which life was only a brief episode. [8] [9]

Eminescu often expressed similar ideas associating death with an existence beyond time and space. One of his last poems, 1886’s “To the Star,” can be read as a concise summarization of his views on death in relation to the cosmos:

‘Tis such a long way to the star

Rising above our shore —

It took the light to come this far

Thousands of years and more.

It may have long died on its way

Into the distant blue,

And only now appears its ray

To shine for us as true.

We watch an icon slowly rise

And climb the canopy —

It lived when yet unknown to eyes:

We see what ceased to be!

And so it is when yearning love

Dies in the deepest night:

Extinct, its flame still glows above

And haunts us with its light. [9] [10]

“We see what ceased to be!” This view of the universe places Eminescu in the grand tradition of philosophical pessimism, from Schopenhauer to Oswald Spengler. It can be compared to Spengler’s Heraclitean notion of the “Becoming” and the “thing-Become,” in place of the Platonic idea of “Being.” But instead of Spengler’s Goethean organic metaphors for the primacy of Becoming, “To the Star” returns this pre-Platonic orientation back to the celestial fire of Heraclitus himself.

Nagy-Talavera writes of the “Eminescian” attitude of “pessimistic resignation.” [10] [11] As with much of the great tradition of German pessimism in which he wrote, “resignation” is a misnomer for Eminescu’s purpose. Like that of Schopenhauer and later Spengler, Eminescu’s pessimism is intended to be provocative, not despair-inducing. He ends “Glossa” by reiterating his inspiring refrains:

You remain aloof and cold

If they urge you, if they cheer;

Rising waves can never hold,

Have no hope and have no fear;

You must think and ask of you

What is right and what is wrong;

All is old and all is new,

Time goes by, time comes along. [11] [12]

[13]

[13]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here [14]

Nationalist Ethics

While studying in Berlin, notes Brackob, Eminescu translated Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason into Romanian. According to Brackob, “Kant’s philosophy would have a profound impact on Eminescu’s literary work.” [12] [15] However, like an equally if not even more profound influence on his outlook, Schopenhauer, Eminescu came to a radically different ethical conclusion than Kant. Kant’s universalistic ethics can be seen as a negative influence on Eminescu, who reversed them in favor of a purely nationalist morality. Nagy-Talavera explains why Eminescu considered Romania’s ethnic character to be the nation’s first priority:

Because, if Romanians would loose their unique national characteristics, they would also loose their right to survive. For Eminescu this ethnicity transcended everything. Any means were justified for its preservation; values, individuals — even facts! — were important only as long as they contributed to the fundamental goal: the preservation of the nation and safeguarding of the national interest. This was so paramount of a significance to Eminescu that it was to be protected even at the cost of employing methods of duplicity, and sacrificing one’s integrity of humaneness. [13] [16]

One of his poems, “Doina,” is mostly themed after the loss of the Moldavian region of Bessarabia to the Russian Empire in the 19th century, but more generally it’s a manifesto advocating his nationalist ethics. One stanza in the poem, later a favorite of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, translates to “He who loves strangers / May the dogs eat out his heart.” Brackob renders that part of the poem thus:

He who loves the foes about

May his heart the dogs rip out,

May desert his home efface

May his sons live in disgrace! [14] [17]

The same poem invokes Christian themes, but certainly not in the service of any ideal of a brotherhood of man:

Let the saints and their deeds

In the trust of pious priests,

Let them ring the bell with might

All the day and all the night,

And may mercy grant thee Lord

Redeem thy people from the horde. [15] [18]

Another poem, translated both by Popescu and by Petre Grimm as “Satire III,” begins with “a Sultan, ruler over nomad bands” being seduced by the moon. [16] [19] The moon tells the Turkish ruler:

Let be our lives united, my pain let yours unfold

That through your sorrow’s sweetness my sorrow be consoled. . .

Writ was it through the ages and all the stars record

That I shall be your mistress, and you shall be my Lord. [17] [20]

Energized by this lunar power, the sultan then conquers much of Asia, Africa, and Europe until he confronts the Wallachian prince Mircea the Elder. The first part of the poem glorifies the feats of Mircea in fighting back the Turks, which are also described in a history book by Brackob. [18] [21] Mircea, who was the grandfather of Vlad Tepes, represents the ethos of defense of the country.

The second part of the poem focuses on contemporary Romania. In Eminescu’s opinion, his age is corrupt, cowardly, and lacking in the heroism of the past. He ends the poem by begging one of Romanian history’s most famous figures to reappear: “How come you do not come back, Lord Țepeș?” Eminescu concludes by calling for the resurrected Vlad Țepeș to round up the modern degenerates, lock half of them in a prison and the other half in a lunatic asylum, and set both on fire.

Political and Economic Views

Eminescu’s views on political economy reflect those of his teacher, Eugen Dühring, the forgotten father of Prussian socialism over two generations before Spengler. Dühring’s excitingly polemical book on the Jews has been translated into English by Alexander Jacob in two available editions, both with Dr. Jacob’s informative introduction. [19] [23] On the other hand, Dühring’s relatively less controversial books have not. This is surprising, as his work on the philosophy of science exerted a profound negative influence over both Nietzsche and Friedrich Engels. [20] [24]

Like Dühring, Eminescu was critical of parliamentary institutions and usury. Also like Dühring (and Bismarck), Eminescu recommended the work of German nationalist economist Friedrich List. We see in Old Icons, New Icons that Eminescu also argues many of his teacher’s main points on capital and labor, applying them to the contemporary Romanian situation. “Labor is the basis of political economy,” affirms Eminescu, adding that “any professional institution can only rely on the reality of labor.” [21] [25] However, Eminescu did not describe himself as a socialist; he criticized the contemporary socialist ideology of August Bebel. A better word for Eminescu’s economic sensibilities would be Dühring’s term “Socialitarian.”

In addition to economics, Eminescu also wrote on the pressing questions of national identity in his troubled region of Europe. It is true that he wrote first and foremost for his own nation, and like most other 19th century nationalist thinkers, often to the exclusion of other Europeans. However, Romania’s territorial rivals and Bulgarian immigrants were not the main enemies in his overall worldview. That position was reserved for the Jews, the Phanar, and Romanian liberals — in that ascending order.

Some of his most venomous work was aimed at the Russians for Russifying (and even worse, Judaizing) Bessarabia, but as Romanian historian Ion Coja has shown, Eminescu distanced his criticism of Russia from that found in what he considered the liberal and Jewish-influenced Western press. “Doina” was written before the age of total war; Eminescu’s stated war aims in it are very concrete, and in no way does he advocate the annihilation of Romania’s enemies as nations. He regarded Bulgarian immigrants to Romania as diluting his country with inferior stock, but he also defended the Bulgarians in his criticism of the Ecumenical Council’s 1872 ruling against them — the one from which the excommunicable Orthodox charge of “ethno-phyletism” derives.

Even his anti-Semitism was more qualified than that of his teacher, Professor Dühring. Eminescu made one major exception to his opposition to any Jewish citizenship: The few Jews who had fought in Romania’s 1877 War of Independence. He was also interested in the cultural differences between different branches of Jewry. Like Houston Stewart Chamberlain a generation later, Eminescu considered Sephardic Jews culturally superior to Ashkenazi Jews.

Eminescu’s ethnically charged animosities were in the final analysis contextual, not absolute. An exception was his hostility to the Phanariot Greeks, but that was for him a religious crusade, not 19th-century chauvinism. In his opinion, the Phanariots had ruined not only his country, but much of his entire Church and the associated civilization.

[26]

[26]You can buy Greg Johnson’s White Identity Politics here. [27]

Lucifer, the Evening Star: A Disputed Translation

Eminescu’s best-regarded and longest poem is “Luceafărul.” In English translation, it is also his most controversial poem, because translators are divided on how to render the title character. The most common English titles are “Lucifer” and “Evening Star,” although translations of the same poem into “Morning Star” exist. “Morning Star” is probably the most accurate literal translation, but “Evening Star” is thought to make more sense, because the poem’s story takes place mostly at night. The original Romanian word refers to Venus as seen from here on Earth.

This has led to a debate among translators over whether or not to translate the title as “Lucifer.” Proponents of “Lucifer” argue that “Evening Star” lacks the personality of Eminescu’s character. Critics of the “Lucifer” translation argue that it gives the poem Satanic connotations that are not in Eminescu’s poem.

The poem begins by introducing a beautiful princess, later named as Catalina, whom the title character adoringly watches from the sky. One night, she summons him:

Oh, gentle star, glide on a beam

To be with me tonight —

Come to my room, make true my dream. . .

My life fill with your light! [22] [28]

The title character then dives from his home in the sky into the sea. He emerges from the sea, and is described as having “golden hair” and sparkling eyes. He asks Catalina to marry him, but she rejects this proposal:

O, beautiful you are, good Sire,

As but an angel prince could be,

But to the course that you desire

I never shall agree

Strange, as your voice and vesture show,

I live while you are dead

Your eyes gleam with an icy glow

Which fills my soul with dread. [23] [29]

Days later, she again waits until nightfall, then summons him once more. Again he descends from the sky, only this time he is described as having dark hair. He again asks her to leave Earth behind and marry him. Again, she relents:

O, beautiful you are, good Sire,

As but a demon prince could be,

But to the course of your desire

I never shall agree

You wound me with your crude behest

I dread what you extol

Your heavy eyes, as though possessed,

Gleam down into my soul. [24] [30]

This time, he protests that he cannot appear otherwise, because unlike her, he is immortal. She responds that if he wants her to marry him, he should live on Earth as a mortal like her. He replies in the affirmative, and then returns to the heavens to ask God for permission.

The plot then takes a turn and introduces “young Catalin, a cunning palace page” who seduces Catalina. [25] [31] Meanwhile, the title character, who is identified with the Titan Hyperion, asks God to let him renounce his immortality. God refuses, saying:

To be a human is your call?

A man — is that your mind?

Oh, let the humans perish all,

Others would breed in kind.

Men only build to nothingness

Vain dreams in noble guise

When waves to silent tomb quiesce

New waves again will rise.

Men merely live by stars of luck

And star-crossed fatefulness

We have no death to prove our pluck,

Nor place or time possess.

From the eternal yesterday

Today lives what will die

Should sun from heavens once decay

New suns would light the sky

And seem to rise to endless morn

While death in wait would lie —

For all die only to be born

And all are born to die!

But you, Hyperion, shall live

Wherever you may set. . .

So ask me now the Word to give,

That wisdom you can get?

Or maybe. . . Give you voice and bring

Sweet music to your song,

So forests in the mountain sing

And oceans hum along?

Justice, perhaps, you wish to make?

Your strength with deeds to prove?

The earth in pieces I could break

So you can kingdoms move!

I’ll give you armies march in stride

To steal the world its breath;

Long ships upon seas fair and wide. . .

But I won’t give you death! [26] [32]

One evening, as Catalin and Catalina embrace under the linden trees, Catalina gazes upon the Evening Star and once again asks him to come to her room that night. The poem concludes with Hyperion’s decision:

As time before, o’er dales and woods,

He quivers ‘mong the trees,

His light still guiding solitudes

On ever-moving seas;

But would not fall again from sky

To sea, as yester day:

“What do you care whether ‘tis I

Or other — face of clay!

In human sphere of narrow lore

May that your luck will hold –

As I remain for ever more

In my eternal cold.” [27] [33]

Did Eminescu intend to associate his hero with the mythology of Lucifer? The poem certainly reflects the ancient Classical view of Lucifer, also identified with Venus seen from Earth, as the “light-bringer.” But what of the Christian mythology of Lucifer?

The morning star is portrayed as a force of destruction in the Old Testament (Isaiah 14:12). Christian theologians, such as Origen and Tertullian, later used this verse to identify Lucifer as a fallen angel who became the devil himself. This interpretation was common by the time it crept into the King James translation. On the other hand, Luther and Calvin dismissed such an interpretation of that verse. The association of the morning star with Satan is further complicated by the fact that the New Testament (Revelation 22:16) refers to Jesus as a “morning star.” Accordingly, a hymn written by Church Father Hilary of Poitiers identifies Jesus with Lucifer, in the original Classical sense of the light-bringer.

In his book on Holy Grail myths and sagas, Julius Evola observes that “the texts of the Grail mention frequently and openly Lucifer’s temptation by a woman,” even though “Lucifer’s action traditionally has never had anything to do with a sexual temptation.” [28] [34] To the extent that Eminescu’s character has Luciferian overtones, the poem tells a similar story. And yet, even if we accept that his character was intended to have anything like Satanic connotations, Eminescu’s poem cannot be said to belong to the Byronic cliché of Satan as a rebellious Romantic hero, because in Eminescu’s telling the patriarchal hierarchy among God and the devil is fully restored.

The poem explores both the positive and the negative associations of Lucifer mythology. The title character brings light wherever he goes, and the poem ends with him dutifully resisting temptation according to God’s command. On the other hand, he is identified with a Titan rather than an Olympian; Titans are often symbols of the demonic. Throughout the poem, Hyperion appears both as an “angel prince” and a “demon prince.” The spiritual ambiguity of “Luceafărul,” especially in English translation, reflects the morally ambiguous mythological status of Venus as seen from our planet.

Eminescu and the Schopenhauerian Nationalist Tradition

The translations produced above, while solid as far as they go, do not do justice to Eminescu’s poetry. Having studied musicology in Berlin, with a focus on Beethoven and Wagner, Eminescu was a master of the aural aspects of Romantic poetry. In addition to the translatable profundity, his poems contain an untranslatable quality of enthralling musicality. English translations are incapable of capturing the intoxicating effect of listening to his work recited in the original Romanian, just as no translation from the original English can capture the hypnotic rhythm of Poe’s “Annabel Lee” or Kipling’s best verse.

Be that as it may, the vivid imagery and deep philosophical speculation of Eminescu’s poetry is almost fully comprehensible in English translation. Nobody would deny that the poems of Goethe, Schiller, and Hölderin — the latter, by the way, being a favorite of Eminescu’s — lose a great deal in translation. Yet those German greats are translated anyway, because of the philosophical value of their poetry. Eminescu deserves to be read in translation for the same reason.

He is important not only for his impact on the development of Romanian literature, or for his influence on the 20th-century Romanian nationalist ideologies of Nicolae Iorga, A. C. Cuza, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, and Ion Antonescu. (The young A. C. Cuza knew Eminescu personally, and was involved in the production of one of the few existing photographs of Eminescu.) [29] [35] To an underrated extent, Eminescu is also important for the intellectual tradition his work points to.

Eminescu sublimely translated German ideas into a Latin language, a language that had not yet found its literary center until he gave it one. His taste in German ideas was no mishmash, however. It places him in a discernable intellectual tradition.

Nietzsche is only the most popular disciple of that tradition, which begins with Schopenhauer. It also includes Richard Wagner and Eugen Dühring. Eminescu discovered Nietzschean concepts independently of Nietzsche because he was likewise a great mind steeped in Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Dühring. In a book on an unrelated subject, scholar Michael Kellogg traces a German metapolitical tradition from Schopenhauer to Wagner to Houston Stewart Chamberlain. [30] [36] Eminescu is an example of what that tradition inspired along the way.

Eminescu’s work therefore counters the way Nietzsche is taught and marketed today. Universities and bookstores present Nietzsche as an anomalous thinker whose work can be properly understood without Schopenhauer — which is intellectually akin to eating one’s dessert first. Certainly, there are radical differences between Eminescu and Nietzsche, but Eminescu’s work demonstrates the value of the Schopenhauerian intellectual (and metapolitical) tradition from which Nietzsche came.

Somewhere in the 1986 interview entitled, in English translation, The Details of Time, Ernst Jünger says that in his nationalist years he had been inspired by the words of the French thinker Maurice Barrès: “I am not national. I am a nationalist.” This could describe Eminescu insofar as he was a “European” thinker by nature, and had to try hard to make his ideas “national.”

Aspects of Eminescu’s work only apply to Romanian or Eastern European problems and are of seemingly no interest to Westerners. Yet even these parts of his oeuvre have an almost universal quality to them, with such poetic power that the context no longer matters. It is the universality of anti-universalist ethics. “Doina” ends, according to Brackob’s translation:

All our enemies will be slain

And our borders we regain,

That the crows may hear their cry

Above the gallow trees so high. [31] [37]

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [38] Nicholas M. Nagy-Talavera, Nicolae Iorga: A Biography, 1998, The Center for Romanian Studies, Portland, p. 66, p. 69

[2] [39] William O. Oldson, A Providential Anti-Semitism: Nationalism and Polity in Nineteenth-Century Romania, 1991, The American Philosophical Society, Independence Square, Philadelphia, p. 115, p. 117

[3] [40] Nagy-Talavera, Nicolae Iorga, p.13

[4] [41] Tr. Adrian George Sahlean, Mihai Eminescu: The Legend of the Evening Star & Selected Poems & Prose, 2020, 2021, Global Arts Inc., p. 17

[5] [42] Ibid, p. 19

[6] [43] Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays, Volume 2, 2015, 2017, Cambridge University Press, p. 242

[7] [44] Ibid, p. 245

[8] [45] Ibid, p. 246

[9] [46] Sahlean, Mihai Eminescu, p. 25

[10] [47] Nagy-Talavera, Nicolae Iorga, p. 71

[11] [48] Sahlean, Mihai Eminescu, p. 21

[12] [49] Ed. A.K. Brackob, Poems and Prose of Mihai Eminescu, 2019, Center for Romanian Studies, Histria Books, Las Vegas, Nevada, p. 13

[13] [50] Nagy-Talavera, Nicolae Iorga, p. 13 (Note: Nagy-Talavera’s confusing use of the word “loose” is, in this context, a synonym for “surrender.”)

[14] [51] Ed. Brackob, Poems and Prose of Mihai Eminescu, p. 20

[15] [52] Ibid

[16] [53] Ibid, p. 55

[17] [54] Corneliu M. Popescu translation (here [55])

[18] [56] A.K. Brackob, Mircea the Old, 2016, The Center for Romanian Studies, Buffalo, NY

[19] [57] Tr. Alexander Jacob, Eugen Dühring on the Jews, 1997, Nineteen Eighty Four Press, and Eugen Dühring, The Jewish Question as a Racial, Moral, and Cultural Question, 2019, Ostara Publications. Dühring’s relation to Spengler’s conception of Prussian socialism is discussed in Alexander Jacob’s introduction to Eugen Dühring and the Jews, pp. 33-38.

[20] [58] Dühring’s influential work on the philosophy of science went through several editions, and is available in German under the title Logik und Wissenschaftstheorie.

[21] [59] Mihai Eminescu, Old Icons, New Icons, 2020, Amory Stern, San Diego, CA, p. 104, p. 108

[22] [60] Sahlean, Mihai Eminescu, p. 37

[23] [61] Corneliu M. Popescu translation (here [62])

[24] [63] Ibid

[25] [64] Sahlean, Mihai Eminescu, p. 47

[26] [65] Ibid, pp. 57-59

[27] [66] Ibid, pp. 61-63

[28] [67] Julius Evola, The Mystery of the Grail: Initiation and Magic in the Quest for the Spirit, 1997, Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont, p. 78

[29] [68] For an overview of A. C. Cuza’s career and influence, see Amory Stern, The Sword of Michael: Origins of Nationalist Politics in Romania and Moldova, 2020, Amory Stern, San Diego, CA, pp. 28-51

[30] [69] Michael Kellogg, The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and the making of National Socialism 1917-1945, (New York; Cambridge University Press, 2005) pp. 20-25

[31] [70] Ed. Brackob, Poems and Prose of Mihai Eminescu, p. 20