Galaxy Quest: From Cargo Cult to Cosplay

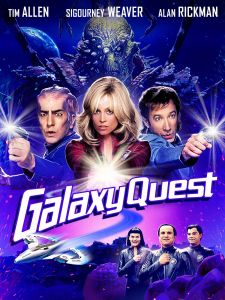

Posted By James J. O'Meara On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledGalaxy Quest (1999)

Director: Dean Parisot [2]

Writers: David Howard (story), Robert Gordon, and David Howard [3] (screenplay)

Stars: Tim Allen [4], Sigourney Weaver [5], Alan Rickman [6], Tony Shalhoub [7], Sam Rockwell [8], Missi Pyle [9]

“It’s really a very sophisticated movie. . .” “. . . with eight-year-old audiences.”

— Sigourney Weaver and Dean Parisot

“Well, fuck this!”

— Sigourney Weaver as “Gwen DeMarco” as sexy communications person “Lt. Tawny Madison”

Before Nerd Culture became not just acceptable but dominant, before blockbuster comic book movies and TV series capeshit filled screens big and small, before ComicCon was national news, there was Galaxy Quest.

In a lot of ways, that was a better world. But you should still watch Galaxy Quest; hear me out.

If you haven’t seen it, do so. Until then, perhaps reflecting the level of fan interest, IMBD offers an unusually rich array of summaries [10]. If you only want to invest the minimum of time, there’s this remarkably concise one:

The alumni cast of a space opera television series have to play their roles as the real thing when an alien race needs their help. However, they also have to defend both Earth and the alien race from a reptilian warlord.

— Kenneth Chisholm [11]

If this elevator pitch gets your attention, a later meeting over lunch at Bob’s Big Boy will spell it out a bit more:

The sci-fi television series “Galaxy Quest”, which took place aboard the intergalactic spaceship NSEA Protector, starred Jason Nesmith as suave Commander Peter Quincy Taggart, Gwen DeMarco as sexy communications person Lt. Tawny Madison (a role which consisted solely of repeating what the computer stated, much to Gwen’s chagrin), Shakespearean trained Sir Alexander Dane as alien Dr. Lazarus, Fred Kwan as engineer Tech Sergeant Chen, and Tommy Webber as child pilot Laredo. Eighteen years after the series last aired, it lives on in the hearts of its rabid fans. However, it lives on in infamy for its stars, who have not been able to find meaningful acting work since. Their current lives revolve around cashing in on [what]ever those roles will afford, which usually entails attending fan conventions or worse, such as electronic store openings. Only Jason seems to relish his lot in life, until he finds out that his co-stars detest him because of his superior attitude as “the Commander”, and much of the public considers him a laughing stock. Their lives change when Jason is approached by who he thinks are convention fans asking for help. They are in reality an alien race called Thermians, led by Mathesar, who have modeled their existence after the series, which they believe to be real. When Jason and then the rest of his co-stars (along with Guy Fleegman, who was killed off before the opening credits in only one episode) go along with the Thermians, Jason’s co-stars who believe they are off to yet another paying gig, they learn that they have to portray their roles for real. Without screenwriters to get them to a happy and heroic ending, they have to trust that their play acting will work, especially in dealing with the Thermians’ nemesis, General Sarris. Guy in particular fears that he will go the way his character did in the series [12]. But when they run across technical issues that they as actors didn’t care anything about during the filming of the series and thus now don’t know how to deal with, they need to find someone who should know what to do.

— Huggo [13]

Are you hooked yet? Do you want to find out what happens next, and who will “know what to do”? Then feel free to consult the insanely comprehensive Synopsis, modestly offered at IMDB without byline, but approaching Pauline Kael’s book on the cutting continuity of Citizen Kane in detail.

But if you are still wondering why we’re looking at this nerd movie, allow me, in the spirit of Woody Allen pulling Marshal McLuhan out from behind a lobby poster [14], to adduce the evidence of no less than legendary screenwriter David Mamet:

“The Godfather, A Place in the Sun, Dodsworth, Galaxy Quest — these are perfect films.” [1] [15]

Although Mamet lauds both actors and screenplay, the film was only modestly successful at the time (we’ll look at the reasons why) but word of mouth and home video worked their usual magic to turn it into a “cult hit.” After twenty years, it was recently the subject of a documentary: Never Surrender: A Galaxy Quest Documentary [16]. (And if you don’t want to invest an hour and a half on it, JoBlo’s WTF review [17] from just last month is a quick twenty minutes.) [2] [18]

Mamet is right to laud the actors and screenplay, but most people, including your humble scribe, find other reasons to single out the film. [3] [19] But first, something about the production.

If you are still undecided, the manly readers of Counter-Currents might take note that Galaxy Quest emerges from the Breaking Bad universe. [4] [20] Producer Mark Johnson had been a judge at a screenwriting competition which was won by Vince Gilligan; Johnson subsequently produced Gilligan’s first film, Home Fries, and later served as Executive Producer for Gilligan’s Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul; Home Fries in turn was directed by Dean Parisot, who would (eventually) helm Galaxy Quest.

Johnson loved David Howard’s idea of having washed-up sci-fi actors confronting real aliens but wanted Robert Gordon to rewrite the script. Gordon’s first draft was greenlit by an enthusiastic DreamWorks. Now the problems started.

What filmmakers haven’t dreamed of having the full support of their financiers and distributors, especially a marquee company like Dreamworks? Alas, and ironically, given the movie’s theme, it was a lesson in “be careful what you wish for.” As Tony Shalhoub (who appears here as Tech Sgt Kwan) told us in 1991’s Barton Fink [5] [21] (reviewed by Trevor Lynch here [22]), never let the studio take an interest in you [23]! [6] [24]

Gordon had added a lot of humor to the script [25], and DreamWorks seemed to think they were getting another Spaceballs. With this in mind, although Johnson had wanted to work with Parisot again, they insisted on hiring Harold Ramis to direct. [7] [26]

Though Ramis was indeed a successful comedy director, his recent outing with Robin Williams, Club Paradise (1986), had flopped, and he now wanted to work with an action star doing comedy, rather than a comedian doing an action role (although Allen, a sci-fi fan, had wanted to play the role “straight”). [8] [27] Moreover, Ramis also didn’t want anyone involved with sci-fi, despite Sigourney Weaver — who had worked with him on Ghostbusters — expressing an interest in the role: “Frankly, it’s those of us who have done science fiction movies that know what is funny about the genre.” After a few tense lunch meetings, Ramis bowed out, and Parisot had his chance to direct Allen and Weaver. [9] [28]

After that speed bump, GQ continued to benefit from the studio’s largesse. Special effects would be provided by the legendary Stan Winston [29] (practical) and Industrial Light and Magic (CGI), while David Newman would contribute a surprising and appropriately majestic soundtrack (played here [30] by the City of Prague Philharmonic) that, like the design of the NTE-3120/NSEA-Protector [31], seems less like a parody of Star Trek and more like a better version from an alternate time series. [10] [32]

Meanwhile casting continued, with established stars like Alan Rickman and Tony Shaloub, as well as newcomers like Sam Rockwell [33] [11] [34] and Missi Pyle. [12] [35]

When cameras began to roll (remember when cameras rolled?) the production also benefited, if one may say so, from the death of Oliver Reed, which threw the production of Gladiator into chaos and took Dreamworks’ attention off GQ. [13] [36] As a result, Parisot and his dream team of actors were free to go deep into each character and even improvise freely if a scene called for it, without having to check back and forth with the suits back at the office. [14] [37]

Unfortunately, by the time distribution came around, Dreamworks had decided they needed a film to compete with Stuart Little for the kids and zeroed in on what they remembered as being a screwball comedy that, with a few judicious touches, would be marketed to “the whole family.”

For some reason, the focus of the cuts seemed to be on Weaver’s Lt. Tawny Madison; her “F-bomb” during the climactic confrontation with the Chompers [38] was dubbed (deliberately badly); moreover, a scene was cut that explained why her uniform was unzipped during the whole of the second half:

Parisot recalls the specific details of the scene, where two aliens get the drop on Allen’s commander Taggert and Weaver’s lieutenant Madison. One of the aliens finds himself strangely attracted to Weaver’s character and his fellow soldier is disgusted by his friend’s “perversion.” The sequence, ultimately comparing an alien’s attraction to a human as bestiality, did not survive the DreamWorks axe. [15] [39]

[40]

[40]You can buy James O’Meara’s book Green Nazis in Space! here. [41]

But DreamWorks was okay with leaving her bra exposed for the rest of the film, so luckily no re-filming or censoring was demanded. Also oddly, Chen’s trans-species romance with Laliari (who is basically an extraterrestrial squid — shades of Lovecraft! [16] [42]) was kept; apparently, bestiality is okay as well, as long as it’s male on alien; or is it because Chen’s character is supposedly Asian anyway? [17] [43]

Anyway, despite these and other examples of classic studio fuckery, the film did reasonably well, but nowhere near what it should have returned, as demonstrated by its continued popularity. The elements already cited would lead one to expect a great film; although opinions may differ, the consensus on the truly great moments seems to focus on two: where Cmdr. Taggart is forced to enlighten the alien leader Mathesar about “acting” — “We pretended. We. . . lied [44]” — and Dr. Lazarus swearing to avenge the death of his alien assistant, Quellek. [18] [45]

Although Rickman was known as “Miss Congeniality” for his professional behavior on sets, he had no illusions about Tim Allen, whose boisterous vulgarity seemed to enable him to play a William Shatner character with no effort at all. [19] [46] But when Allen nailed his scene, and even had to retreat to his trailer to recover (muttering “I don’t like these feelings”), Rickman observed with a mixture of respect and irony: “I think he just experienced acting.”

Rickman’s scene is best appreciated, I think, as the climax of a character arc that begins already under the opening credits; what I call the “Grabthar’s Hammer arc” can be seen edited together here [47]. Rickman’s performance is a veritable “For Your Oscar™ Consideration” reel, as he takes “Alexander Dane” from angry frustration, to cold contempt, to bored resignation, and ultimately delivering the line for the first time with real meaning. The first thing Dane says to us is that his Richard III received five curtain calls, but only when Quellek’s death brings home to him his influence on popular culture, and its importance, does he “experience acting.”

Apart from being individual high points, the two scenes are somewhat like bookends. Both are two-shot setups with a human and an alien in extremis, of course. Moreover, in each, an actor — played of course by a “real” actor — is forced to confront the implications of his playacting. Taggart and crew have — quite innocently — misled an alien race into believing they can save them from extermination by the reptilian warlord Sarris; [20] [48] Dane discovers he has “been a father” to an alien he never knew about, and his importance to the fans he treated so contemptuously before. Taggart is forced to admit to lying; Dane, seeing that Quellek is mortally wounded, offers the usual comforting lie: “that’s not too bad.” Malthesar presumably lives, although he now knows he lives in a world of lies; Quellek dies, but because Dane is finally able to utter his catchphrase “once more with feeling” [21] [49] — “By Grabthar’s hammer, by the suns of Warvan, you shall be avenged” [22] [50] — he knows his life will have meaning, or at least a satisfying conclusion.

Here especially, Patrick Breen as Quellek looks and sounds like Jim Parsons’ Dr. Sheldon Cooper, and one can’t help but recall the moment when Sheldon confessed how much the discovery of Mr. Spock meant to him as a child in rural Texas. [23] [51]

All of this would give the reader reason enough to check out the film; Constant Readers may suspect that I have another reason to value this film, and they would be right. Galaxy Quest explores the phenomenon of fiction becoming fact, the main point of the teachings of the midcentury mystic, Neville Goddard, which I have explored here and elsewhere. [24] [52]

That actors are the subject is no accident. Neville’s “simple method for changing the future,” which I’ve discussed here many a time, crucially combines both physical relaxation (the body) and visionary intensity (mind and will); conversely, Mitch Horowitz notes that most New Age practitioners of “the law of attraction,” “the Secret,” and so on fail because they seem to think they can rely on “wishful thinking” alone. Neville was initially both a dancer and an actor on Broadway, and Horowitz and others believe his physical training suggested, and enhanced, his ability to attain states of deep relaxation. Horowitz also explicitly mentions “method” acting as an analogy to Neville’s own “method,” which involves embodying one’s goal in a small dramatic scene, which is rehearsed again and again in imagination, until it acquires the tones of reality. [25] [53]

You will have noticed that I’m talking about the actors, or the “actors.” I suppose conventional wisdom would be that the Thermians illustrate how “wishing makes it true,” but I think that would be wrong. The Thermians know nothing of lying, so they know nothing of acting, or more importantly, imagination. You might imagine acting or imagining as a positive pole of which lying is the negative.

The Thermians are simply a cargo cult; they do not so much believe “if you built a starship the crew will come” but that “if you build a starship, you can kidnap the crew and make them help you.” They remain, as Nietzsche would say, “subservient to reality.”

A conventional point of view would call the Thermians “good,” but they are not good, merely innocent and naïve (dangerously so); they have grasped the importance of dreams but not the need to act (note the ambiguity of the word) as well. Conversely, we (if I may pompously speak for the audience, which itself is rather self-satisfied) have nothing to be proud of with our enslavement to mere “facts”; if we remain as such, we will “die in our sins.” [26] [54]

The actors of the original TV series, by contrast, have been doing what they do best: acting. After the original series ended, they have spent the better part of twenty years reliving those parts; they are even forced to re-enact their parts at conventions and supermarket openings. [27] [55]

At the same time, they have yearned for a chance to give their lives more meaning; Taggart wishes to be regarded as a great actor and heroic leader of men, not a ham and a pompous ass; [28] [56] Guy wants to survive beyond the opening credits, etc.

The disdainful Dane provides the most detailed example. It’s notable that although he despises his role, we never see him throughout the entire movie without his alien headpiece. . . even in a brief scene at his tiny apartment after the opening convention. Now there’s a method actor! [29] [57]

The first thing Dane tells us about himself is that he was a great Shakespearean actor, a fact that he apparently references constantly, to judge by his co-stars’ reactions (“Not again.” “Five curtain calls.”) He has been rehearsing his scene with Quellek all this time: Alas, poor Quellek! [30] [58] “Though we never met, I have always considered you a father.” Dane’s wishes are father to this fatal fact. [31] [59]

The death of Quellek — like the others that occur during this rather serious, not at all Spaceballs-like “comedy,” perhaps including the entire galactic war itself — [32] [60] illustrates an interesting aspect of Neville’s method. As he demands repeatedly, one visualizes the end, not the means; the universe will marshal its unlimited resources and bring about the result in ways you know not. That’s reassuring in some ways, but there’s a sting as well.

In Neville’s favorite, repeated example, “How Abdullah Taught Neville the Law [61],” his desire to visit his family in Barbados for Christmas, despite being penniless in New York City, results in his brother “suddenly deciding” to have a family reunion, for which he sends Neville a steamship ticket and money for clothes, drinks, and tips along the way. In another, and a personal favorite of mine, Neville obtains tickets for a sold-out performance at the Met [62] when he notices a con man in front of him in the ticket line; the grateful clerk provides him with free VIP tickets.

How charming. But, there are a surprising number of occasions where Neville must reassure someone who made use of his method and seemingly brought about someone’s death, as an apparently accidental result of merely wishing for a little peace and quiet. [33] [63]

Hence, another importance of visualizing only a deeply felt desire; Neville treats such desires as literally God-given, which not only makes the realization likely, but absolves you of responsibility for the means. Instead, it is the universe that will create what he calls “a bridge of incidents [64]” — am I allowed to let this recall the bridge of a starship? — that will, in turn, lead to the realization of your deeply felt desire. [34] [65]

That “bridge of incidents” is related to a basic principle of New Thought: however woo-woo the method may seem, our goals are realized by “accepted means.” [35] [66] In the examples just given, Neville doesn’t levitate to Barbados, but receives an unexpected ticket; the tickets to Aida don’t materialize in his pocket, he has to wait in line at the ticket booth. [36] [67] Or in this case, Sarris starts a galactic war of extermination and gives our actors their chance to redeem themselves; as we’ve seen, the universe may grant our wishes, but still treats us as straw dogs.

The real story is that the actors yearning for redemption causes the universe to create the bridge of incidents; saving the Thermidians is akin to a McGuffin, not unlike the Omega-13 device (although it does turn out to have an important function). [37] [68]

And life imitates art. Although the movie certainly didn’t harm Rickman’s career as the TV show did Sir Alexander Dane’s, it did profoundly influence it. Younger members of general audiences likely know him mainly as Snape in the Harry Potter series, where, I am told, he snatched an exam from Hermione with the same disdain as he here displays to a “Questian” seeking an autograph [69]; collections of “Rickman’s most memorable performances” after his recent death (which likely ended the chance of a sequel) inevitably included Dr. Lazarus, often in the top 3 or 4 ranks.

I think I’ve given you more than a few reasons to buy or stream Galaxy Quest if you haven’t seen it already, or to see it again. If, like Jim Goad [70], you are “someone who avoids all Hollywood movies after 1975,” you’ll find it refreshingly free of Wokeness. The scene where the token black actor (who had been an Urkel-like child prodigy on the show) has to pretend to know how to take the ship out of drydock is both a satire of the infamous fan service scene of the Enterprise leisurely moving out in the first Trek film, as well as a bit of politically incorrect humor. In the documentary, Shalub notes that while he would never play an Asian role, he was willing to “play a guy who plays an Asian guy.”

Otherwise, the film is refreshingly white, including the aliens. It’s interesting that the aliens, basing their culture and presumably their illusory appearance on TV shows like Galaxy Quest and Gilligan’s Island (“those poor people!”), see no need to even “appear” diverse, and are uniformly white (although, like Missi Pyle and Rain Wilson, a little off).

The doco is excellent, and in fact is the source for most of my background info. It begins and ends a bit dishearteningly, as it takes the view that the significance of the film is that it treated with respect, and thus contributed to the rise, of both nerddom and even cosplay. Counter-Currents readers may be inclined to not find this a good thing; I myself am a bit ambivalent as well, especially regarding the latter, but both have useful analogies to issues faced by the “Dissident Right” as a subculture of its own. [38] [71]

If I may be allowed to go one step further, there may even be a kind of allegory of contemporary politics. The Tea Party was a cargo cult like the Thermians, imagining that dressing up like Tom Jefferson and throwing tea bags around would somehow restore “muh Constitution.” Instead, the universe gave us Trump; as the Z Man recently argued [72], the anger directed at Trump by the Left and the Right has nothing to do with anything he actually did in office, but rather everything to do with his exposing their electoral system as fake, a kind of Dungeons and Dragons for normies.

So, please check out, or revisit, Galaxy Quest. Thank you, and don’t forget to buy your T-shirts on your way out.

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Notes

[1] [73] Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon, 2007), pp. 69-70. Though a loyal Tribesman, Mamet seems to “get” a lot of things, such as the Aryan Männerbunde (see my review of his and De Palma’s The Untouchables [74], reprinted in The Homo & the Negro: Masculinist Meditations on Politics & Popular Culture; Second, Embiggened Edition edited by Greg Johnson [San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017]) and the Liberal echo-chamber [75].

[2] [76] And if you like “YouTuber reacts to first time watching X” videos, as I do, there’s this even more recent one [77], and a really more recent one [78].

[3] [79] If anyone’s interested, Dodsworth is indeed a somewhat obscure gem, starring Walter Huston and Mary Astor, and a surprisingly pro-bohemian screenplay for a Hollywood film (Huston ditches his philistine wife and shacks up in Europe with bad girl Astor). A Place in the Sun bored me, but I suppose it delights those who worship Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor, as it is peak both. I won’t bother to add my two cents about The Godfather, although I prefer Godfather II (which, like American History X — see Trevor Lynch’s review here [80] –– is a pro-immigrant film that actually makes the case for excluding Sicilians).

[4] [81] See Jef Costello’s encomia here [82] and here [83]; consider my own take, here [84], and to be reprinted in my collection Passing the Buck: Coleman Francis and other Cinematic Metaphysicians (Manticore Press, forthcoming).

[5] [85] Shaloub’s perpetually stoned and snacking character reminds me a bit of another Coen Bros creation, the Dude from the previous year’s The Big Lebowski.

[6] [86] The crew at Mystery Science Theater has always credited their initial success to being produced in Minneapolis, which the New York suits at Comedy Central avoided at all costs. After moving to the Sci-Fi Channel (now SyFy Universal), network notes led to a series of disastrous “improvements” and ultimate cancellation.

[7] [87] See my review of his 1993 Groundhog Day, here [88] and reprinted in my collection Passing the Buck: Coleman Francis and other Cinematic Metaphysicians (Manticore Press, forthcoming).

[8] [89] One is reminded of the MST3k remark on Coleman Francis’ The Skydivers: “Instead of having his actors do their own stunts, he had his stuntmen do their own acting.” For more on Coleman Francis, arguably the Z-movie Orson Welles, see my epic, three-part study, “Coffee? I Like Coffee [90],” reprinted in Passing the Buck, op. cit.

[9] [91] “Galaxy Quest: Tim Allen Equates Harold Ramis’ Version to Spaceballs [92]” by Shawn S. Lealos (CBR, January 01, 2020). “For his part, Ramis reportedly conceded Allen was perfect for the role. Producer Mark Johnson said Ramis called him after seeing Galaxy Quest in theaters and said, “it was a great film and that Tim Allen was a fantastic commander.”

[10] [93] You might notice the Protector is the inverse of the Enterprise (cylindrical main section, round engines) and, for legal reasons, belongs to the class NTE (“Not the Enterprise”). The movie itself became so faithful to the original that Trekkies consider it to be a Star Trek movie, even coming in second or third in convention polls.

[11] [94] Rockwell knew his breakout role, in The Green Mile, would come out around the same time, and was eager to show he could do comedy as well as drama. He would win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar™ for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri in 2017.

[12] [95] This was her first major film role, although I recall seeing her perform at the Jekyll & Hyde theme restaurant in New York City a few years before. She’s appropriately cast as an alien, or at least as the cloaked form of one, since she’s the sort of woman who seems attractive yet has something odd or disturbing about her; cf. my remarks on Meg Foster in “He Writes! You Read! They Live [96]!”, reprinted in The Homo & the Negro: Masculinist Meditations on Politics & Popular Culture; 2nd, Embiggened Edition; ed. by Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017), as well as “’The Wild Boys Smile’: Reflections on Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John, Part 2 [97]” and “From Ultrasuede to Limelight: Aryan Entrepreneurs in the Dark Age, Part 1: Halston [98],” both reprinted in my collection Green Nazis in Space! New Essays on Literature, Art, & Culture; ed. by Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2015). In the latter, I note, in reference to “Anjelica Huston, an actual Halston model we see in archival footage and interviews [that her] . . . unusual . . . features suggest a beauty that dwells on other planes than ours; superhuman rather than subhuman, elfin rather than bestial. Like Meg Foster, it would be possible to imagine a production of LOTR where she plays Galadriel, while [Sarah Jessica] Parker suggests nothing more otherworldly than a wicked witch or stepmother.” That her “human” appearance is generated by a cloaking device lends the touch of “uncanny valley.” Since she eventually joins the crew of the renewed TV series also links her to the equally disturbing (though pro-Trump [99]) Kirstie Alley (Saavik in Star Trek II).

[13] [100] See the JoBlo video review, at minute 15.

[14] [101] E.g.: “According to writer David Howard, the continuous melodic yet monotone voice of Thermian commander Mathesar was an original idea that Enrico Colantoni brought to the character. Everyone on the set loved it so much, they kept it in the shoot.”—IMDB.com. In the doco, Colantoni says it was based on a vocal exercise used at Yale Drama School.

[15] [102] Byron Burton, “DreamWorks ‘Screwed Up’: Why Cult Classic ‘Galaxy Quest’ Wasn’t a Bigger Hit [103],” Hollywood Reporter, December 24, 2019. Also weirdly, there’s a similar scene in Space Mutiny [104] (MST3k Episode 920), although only humans are involved. Inter-species loving was a thing with Star Trek, with Kirk pursuing anything vaguely enough human, even if blue, and of course Mr. Spock being the product of a human/Vulcan union (all properly married, of course). Unsurprisingly, it also featured the first interracial kiss on network TV (although being Kirk and Uhuru, I suppose that would be considered workplace harassment today).

[16] [105] One might compare beauty on nonhuman planes to the transdimensional horror of Cthulhu.

[17] [106] Chen finding happiness with his visually disguised alien creature may be a homage to the Star Trek episode “The Menagerie [107],” the two-part episode that repurposed the pilot’s footage of Jeffrey Hunter as Com. Pike.

[18] [108] Personally, if I had to pick a scene that epitomized the film, it would be the aforementioned Chompers. It’s funny, it’s well-acted, the effects are great, the comically bad overdubbing illustrates the studio interference, and the whole concept and dialog drive home the sci-fi satire theme:

Gwen: “What IS that thing? It serves no useful purpose to have a bunch of CHOPPY CRUSHY things in the middle of a CATWALK!? We shouldn’t have to DO this! It makes NO LOGICAL SENSE! Why is it HERE?”

Jason: “Because it was on the show!”

Gwen: “Well forget it! I’m not going. This episode was badly written!”

[19] [109] William Shatner: “I thought it was very funny, and I thought the audience that they portrayed was totally real, but the actors that they were pretending to be were totally unrecognizable. Certainly I don’t know what Tim Allen was doing. He seemed to be the head of a group of actors, and for the life of me I was trying to understand who he was imitating. The only one I recognized was the girl playing Nichelle Nichols.” — IMDB.com

[20] [110] “Andrew Sarris (October 31, 1928-June 20, 2012) was an American film critic, a leading proponent of the auteur theory of film criticism. . . . In 1997, Camille Paglia described Sarris as her third favorite critic, praising ‘his acute columns during the high period of The Village Voice.’”

— Wikipedia [111].

[21] [112] In the first scene: “I won’t say that ridiculous catchphrase one more time. I won’t. I can’t!”

[22] [113] “As with both Grabthar’s Hammer and the Suns of Warvan, the oath is noteworthy for being fictional within an already-fictional universe. As such, it has no direct analog in American English.”

— Frakipedia [114].

[23] [115] Lazarus’s subsequent charge of the bad guy resembles the berserker moment in The Untouchables, complete with the alien’s conveniently jammed weapon.

[24] [116] See, among many places, “Immobile Warriors: Evola’s Post-War Career from the Perspective of Neville’s New Thought,” which explores Neville’s assertion that “There is no fiction” with reference to historical events, from the sinking of the Titanic to Evola’s wounding in the Second World War, that appear to have been inspired by fiction published beforehand.

[25] [117] Mitch Horowitz has conveniently provided us with an even briefer summary of this “simple method”:

To recap the formula: First, clarify a sincere and deeply felt desire. Second, enter a state of relaxed immobility, bordering on sleep. Third, enact a mental scene that contains the assumption and feeling of your wish fulfilled. Run the little drama over and over in your mind until you experience a sense of fulfillment. Then resume your life. Evidence of your achievement will unfold at the right moment in your outer experience.

See my review of Horowitz’s The Miracle Club: How Thoughts Become Reality, here: “Evola’s Other Club: Mitch Horowitz & the Self-Made Mystic [118].”

[26] [119] “For if you believe not that I am he, you shall die in your sin.” — John 6:24. A favorite quote of Neville’s, as was “I have said, Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High. But ye shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes.” — Psalm 82:6-7. Complacency is not enough.

[27] [120] Their original episodes themselves are replayed at conventions and presumably in syndication; I’m not sure if this exactly counts for Neville’s system but in the fictional world it may (Dane refuses to utter the infernal catchphrase at a convention but a clip of Dr. Lazarus projected over Dane’s shoulder does so for him).

[28] [121] Is his character’s name an allusion to Dagny Taggart of Atlas Shrugged?

[29] [122] As Ed Wood (Johnny Depp) first sees Bunny Breckenridge (Bill Murray) as the alien leader in Plan Nine from Outer Space, he marvels “Now that’s an alien [123]!” (Tim Burton’s Ed Wood).

[30] [124] “Dane” itself must be a reference to Hamlet.

[31] [125] The scene recalls any number of similar ones in Shakespeare; the soundtrack helpfully provides the sound of the angels singing him to his rest.

[32] [126] One is reminded of how the “redemption of Anakin Skywalker” occurs despite his being responsible for the deaths of billions of people, torture of who knows how many, etc. (In the digitally-diddled version he even regains his handsome youthful appearance). That the producers are correct in assuming we will treat them as straw dogs [127] is shown as early as the guffaws that greet Obi-Wan’s pathetic cry “You’ve killed younglings!” I suppose it’s because he’s a purely fictional character; similar treatment of Hitler, Stalin, or Mao, mere pikers compared to Vader, is unthinkable.

[33] [128] The lesson of “The Monkey’s Paw.” This 1915 tale has been dramatized endlessly; compare “Let’s Talk About Steve Trevor’s Problematic Resurrection in Wonder Woman 1984 [129].”

[34] [130] For another parallel, this is arguably the arc of the Coen Bros. Burn After Reading, described by a YouTube commenter [131] as: “some selfish woman creating a convoluted scheme to get money for plastic surgery which kills or destroys the lives of everyone who ends up involved, and in the end, she ends up getting exactly what she wants with no remorse or guilt.” The “selfish woman” is played by Frances MacDormand, who would star with Sam Rockwell in the aforementioned Three Billboards; McDormand and Rockwell each won the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, SAG Award, BAFTA Award, and Critics’ Choice Award as Best Lead Actress and Best Supporting Actor.

[35] [132] Studies have shown that medical treatments work best when patients expect them to work; indeed, this was Emile Coue’s original insight. This is entirely different from “faith healing” or “Christian Science” where treatment is avoided entirely. Indeed, Mitch Horowitz encourages what he calls ‘the D-Day approach” and throwing everything you’ve got at a problem, from surgery to visualization; see chapter three of The Miracle Club, op. cit.

[36] [133] Waiting in line at a sold-out show is a perfect example of faith: “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11.1). To paraphrase Sherlock Holmes, when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, is magickal.

[37] [134] The notion of several minds focused on one magical goal recalls Evola’s concept of “magical chains”; see Introduction to Magic: Rituals and Practical Techniques for the Magus (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2001), especially “Opus Magicum: Chains” by “Luce.”

In regard to this, Evola himself wrote that the aim of the “chain” of the UR Group, aside from “awakening a higher force that might serve to help the singular work of every individual,” was also to act “on the type of psychic body that begged for creation, and by evocation to connect it with a genuine influence from above,” so that “one may perhaps have the possibility of working behind the scenes in order to ultimately exert an effect on the prevailing forces in the general environment.” Although this attempt did not meet with its hoped-for success [influencing Mussolini and the course of Fascism]. . .

Introduction to Magic, op. cit., Preface by Retano Del Ponte. This might also be usefully compared with Napoleon Hill’s concept of the “Mastermind”: see Mitch Horowitz, The Power of the Master Mind (G&D Media, 2019).

[38] [135] This is not an endorsement of “costumed Nazis.” Even CPAC was once “generally regarded in elite conservative and Republican circles as merely a circus [136], a Star Trek convention [137], a freak show, even. The undercurrent of these comments and discussions was that while CPAC might be a cross-section of the weird edges of the conservative activist set it didn’t truly represent the seriousness and sobriety of the broader movement.” The Bulwark [138].