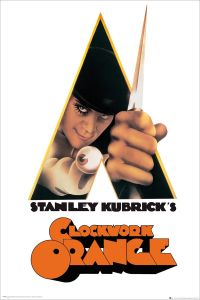

A Clockwork Orange

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledFor years now, readers have been urging me to review Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), which adapts Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel of the same name. I have resisted, because although A Clockwork Orange is often hailed as a classic, I thought it was dumb, distasteful, and highly overrated, so I didn’t want to watch it again. But I had first watched it decades ago. So I thought I might see it differently if I gave it another chance. I approached it with an open mind. But I was right the first time.

A Clockwork Orange is set in Great Britain in a not-too-distant future. Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his three buddies are violent hooligans who engage in rape, assault, robbery, and wanton destruction. The movie opens with an amphetamine-fueled crime spree. They beat up an old drunk, brawl with another gang, run people off the road while joyriding, then use a confidence trick (“There’s been a terrible accident. Can I come in and use your phone?”) to invade a couple’s home, whereupon they beat the man, rape his wife, and trash the place. The whole sequence is deeply distasteful. Violent sociopaths like Alex and his friends should simply be killed.

Alex is high-handed and cruel to his buddies as well, using treachery and violence to assert dominance over them. This merely breeds resentment. One night they decide to rob a wealthy woman’s house. The old accident trick does not work, so Alex breaks in. There is a struggle. She attacks him with a bust of Beethoven, so he kills her with a sculpture of a penis. Hearing sirens, he exits, whereupon his ex-friends clobber him with a bottle and leave him for the police.

Let that be a lesson to you.

Alex is imprisoned for murder. He seeks to ingratiate himself with the authorities by feigning Christian piety. (As a violent sociopath, he finds the Old Testament more to his liking.)

When a new Left-wing government comes into power, they want to free up prison space for political prisoners, so they introduce an experimental cure for his violent sociopathy: the Ludovico technique, which is basically a form of Pavlovian conditioning. Alex is the test subject. He is injected with a nausea-producing drug then forced to watch films of violence, including sexual violence. Eventually, he can’t even think of violence without becoming violently ill. Pronounced cured, he is released into society.

Newly paroled, Alex bumps into the bum that he assaulted, who recognizes him and wants revenge. He calls together his fellow bums to beat Alex, whose Ludovico conditioning makes it impossible for him to fight back.

Ironic, huh?

Let that be a lesson to you.

When the mob of hobos is broken up by two cops, they turn out to be two of Alex’s old gang, the very ones he humiliated. Eager to exact further revenge, they beat him mercilessly and abandon him in the countryside. Alex is helpless to resist.

Ironic, huh?

Let that be a lesson to you.

[2]

[2]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [3]

Alex wanders through the countryside until he takes refuge at the home of the very couple he and his gang brutalized. Ironic, huh? The husband was crippled by the beating. The wife has died and been replaced with a gigantic muscular dork named Julian. The husband figures out who Alex is and drugs him. Then he and some of his friends, who oppose the government that introduced the Ludovico technique, try to drive Alex to commit suicide, hoping to create a scandal that will embarrass the government. Alex throws himself from a window and is severely injured but does not die.

To contain the scandal, the Justice Minister throws the cripple in prison and tries to win Alex’s favor by tending to his wounds. While unconscious, he is also given brain surgery to reverse the Ludovico technique. The happy ending is that Alex returns to being a violent sociopath, but this time he will enjoy the patronage and protection of the state. Thus the tale veers from pat moralism to pure cynicism in the end. Apparently, the book’s final chapter was “redemptive,” but this was omitted as being contrived — as if that weren’t true of the whole story.

But isn’t this all redeemed by a “deep message” about human freedom? No, not really, because the moral psychology of A Clockwork Orange is remarkably crude.

The Ludovico technique is based on the observation that normal people have a distaste for violence and cruelty directed at the innocent. Then it simply ignores the fact that normal people don’t necessarily have a distaste for violence, even cruelty, directed at bad people. It also reverses cause and effect, reasoning that since normal people feel distaste at violence, if they can create a mechanical association between violence and sickness, that will somehow make Alex a morally normal person, curing him of his violent sociopathy.

Of course, this whole theory completely ignores the element of empathy. Normal people feel disgust with violence and cruelty because they can empathize with the victims. Sociopaths lack empathy, and the Ludovico technique does not change that. Alex does not feel sick with empathy for victims, he just feels sick. And his physiological response makes no moral distinctions between violence meted out to the deserving and the undeserving. When he is attacked, he can’t defend himself, because even violence in self-defense makes him sick.

Of course, utter stupidity is no objection to most progressive social uplift schemes, so it doesn’t exactly make such a “cure” for crime implausible.

Burgess’ “deep” objection to the Ludovico technique is equally crude and dumb, but in a different way. The prison chaplain argues that the Ludovico technique is evil because it takes away Alex’s freedom, which takes away his humanity. Alex, being a sociopath, takes pleasure in hurting innocent people. The Ludovico treatment conditions him to feel disgust at violence, which denies him the freedom to do evil, thus it is dehumanizing.

But if this is a dehumanizing assault on freedom, what are we to make of our own disgust with Alex’s behavior? Is that also a dehumanizing form of unfreedom? Presumably so.

Does this mean that when Alex becomes a violent sociopath again his humanity has been restored? Presumably so.

Since Alex the sociopath can contemplate violence without any feelings of disgust, whereas normal people cannot, does this mean that Alex is both more free and more human than normally constituted people? If so, this is a pretty good example of a reductio ad absurdum.

The Ludovico technique and Burgess’ alternative both depend on a pat dualism between body and mind, which leaves no place for what the ancients called virtues and the moderns called moral sentiments. For the ancients, virtue is rooted in habit. For moral sentiments theorists, our ability to perceive the good is caught up in feelings like empathy and disgust. But to the Ludovico technique, virtue is indistinguishable from Pavlovian conditioning, and moral sentiments are indistinguishable from a sour stomach. From the chaplain’s point of view, the freedom of the mind is so separate from the body, habit, and feeling that a sociopath’s lack of virtue or moral sentiment actually makes him freer and thus more human than morally healthy people.

But isn’t Kubrick’s treatment of this material brilliant? No, not really. Kubrick’s treatment of sex and violence veers between the pornographic and cartoonish. The entire movie is crude and cynical parody, with an ugly cast, grotesque costumes, hideous sets, and dreadful over-acting. The whole production reminded me of the comics of R. Crumb, who puts his prodigious talent to work churning out pornography, grotesquerie, and world-destroying cynicism. Crumb obviously hates America. He especially hates women. Likewise, the director of A Clockwork Orange obviously hates everything about Great Britain. He also takes particular pleasure in the mockery and degradation of women. Handling such material with technical skill does not redeem it. Indeed, by making it seductive, Kubrick actually makes it worse.

A Clockwork Orange is violence-porn and porn-porn combined with a middle-brow, moralistic “message” and some classical music. But these function merely as an alibi, like the interviews in Playboy. A Clockwork Orange is obscene in the literal sense of the word: it should not be watched.

The Unz Review [4], April 1, 2021

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: