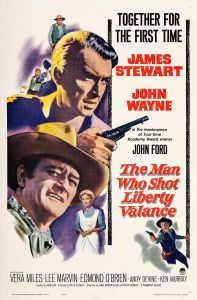

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledJohn Ford’s last great film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) enjoys the status of a classic. I find it a deeply flawed, grating, and often ridiculous film that is nonetheless redeemed both by raising intellectually deep issues and by an emotionally powerful ending that seems to come out of nowhere.

The stars of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance are John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart, both fine actors given the impossible job of playing men in their 20s, even though they were aged 54 and 53 at the time. It just doesn’t work.

There’s also too much buffoonery. Ford thought that drunkards and men with funny voices were hilarious. In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, we get two funny drunkards and three men with funny voices, including Andy Devine and Strother Martin. There is also a great deal of scene-chewing overacting and overbroad parody that often seem downright cartoonish.

The film is poorly paced as well, burning through screen time and my patience with dramatically needless details of frontier kitchens and political conventions.

Beyond these lapses of taste, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance also contains Left-liberal messages on race. For instance, Devine’s Marshal Link Appleyard is married to a Mexican woman. Oddly enough, the same actor’s character in Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) is married to a Mexican as well. In real life, Any Devine was married to a white woman. Bucking the color bar must have been Ford’s preference.

Wayne’s character Tom Doniphan has a loyal negro sidekick named Pompey (Woody Strode). Pompey even endures the indignity of being refused service at the saloon, but Doniphan stands up for him, although he does refer to him as “my boy Pompey.”

At the very center of the film is a scene in which newly-minted lawyer Ransom Stoddard (Stewart) teaches reading and civics to a class of white adults, plus Pompey and a brood of Mexican children. (All the children in Shinbone are nonwhite, a poignant sign that white civilization has not yet been established there. Now such classrooms are signs of white civilization in decline.) Lawyer Stoddard teaches that the fundamental law of the land is the Declaration of Independence, which holds that “All men are created equal.” The Declaration, of course, is not the fundamental law of the land. That would be the Constitution, which says nothing about all men being created equal.

Ford was known as a patriot and an anti-Communist, but on race, his politics were aligned with the Hollywood progressive consensus. Ford did not, however, identify with outsiders against America’s WASP ethnic core because he was Jewish. Instead, he did so as an Irish Catholic, born John Martin Feeney.

Judging from Ford’s cavalry trilogy — Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950) — the West could not have been won without the help of golden-hearted, silver-tongued Irish drunkards. These stereotypes seem rather broad and offensive today, but Ford — a heavy drinker himself — obviously regarded them affectionately and thought their inclusion to be progressive.

I list these problems up front, because I don’t want you to be surprised or deterred by them. For in spite of its flaws, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a worthwhile film. As the title suggests, this is a movie about violence, specifically the relationship of violence to manliness and civilization. The film’s message is deeply anti-liberal. Indeed, although Ford could not have known it, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance illustrates many of Carl Schmitt’s criticisms of liberalism [2]. Thus I include it in my series of Classics of Right-Wing Cinema.

The movie opens with a train pulling into the town of Shinbone in an unnamed state in the American Southwest. Shinbone is conspicuously bright, clean, and attractive. Everything looks brand-new. The only thing old and dusty is the stagecoach, a victim of progress suitably abandoned at the undertaker’s parlor. Shinbone was built on a soundstage. Ford was known for shooting on location because he loved sweeping vistas and gritty authenticity. But Shinbone’s cleanliness and newness — its clear artificiality — were quite deliberate representations of progress and the end of the frontier.

Senator Ransom Stoddard and his wife Hallie (Vera Miles) are met by the former Marshal, Link Appleyard. They have arrived to attend the funeral of their old friend Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), who is being interred in a pauper’s grave at public expense. As a sign of the changes in Shinbone, we learn that Doniphon will not be buried with his gun, because he had not carried one in years. When the local newspaper editor demands to know why a sitting Senator is attending the funeral of a pauper, Stoddard agrees to tell the tale.

We flash back some decades. Ransom “Rance” Stoddard, fresh out of law school, has gone West, not so much to seek fame and fortune as to improve the place by bringing law, literacy, and progress from back East. Outside a much rougher version of Shinbone, the stagecoach in which Stoddard is riding is robbed by outlaw Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) and his gang (including Lee Van Cleef and Strother Martin). When Stoddard objects to the rough treatment of a woman, Valance beats him severely then sends away the coach, leaving him to his fate.

Played to cartoonish excess by Lee Marvin, Liberty Valance is a cold-blooded murderer and thief. He’s also a drunkard and a petty bully. The entire town of Shinbone lives in terror of him. He’s the kind of man who needs killing, so decent people can plant crops, raise children, and sleep at night.

It seems odd that an American movie would have a villain named Liberty. Isn’t America the land of liberty? But Liberty Valance is not really an American. He’s a man of the Wild West. America is a Republic with laws. The West is the state of nature. Liberty Valance represents the liberty of savages in the state of nature, where one man’s liberty is exercised at the expense of another’s. Savage liberty must die so civil liberty can be born. Thus it is appropriate that Liberty Valance is a hired gun of the cattle interests, who oppose statehood and the coming of law and order.

Stoddard is rescued by Tom Doniphon, who owns a small horse ranch outside Shinbone, and brought into town. For no sensible reason except that he likes her, Tom awakens Hallie, who works as a waitress at a local eatery, to help tend to Stoddard’s wounds.

Tom quickly pegs Rance as a greenhorn and a tinhorn. He doesn’t know how the world works, but he talks like he does. When Tom tells Rance that he’d better get a gun if he wants justice, Rance launches into a speech:

But do you know what you’re saying to me? You’re saying just exactly what Liberty Valance said. What kind of community have I come to? You all seem to know Liberty Valance. He’s a no-good, gun-packing, murdering thief, but the only advice you give me is to carry a gun. Well, I’m a lawyer! Ransom Stoddard, Attorney at Law. And the law is the only . . .

Jimmy Stewart was brilliant casting because he’s obviously in love with his own voice.

[3]

[3]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [4]

Rance doesn’t see any difference between force used by criminals and force used by decent men against criminals. He’s an idealist who apparently thinks the laws can magically enforce themselves. In John Wayne’s most often-imitated line, Tom calls Rance “Pilgrim,” which pretty much sums up his combination of moralism and utopianism. He’s a spindly, priggish, progressive zealot. He reminds me of Barack Obama.

Rance settles in Shinbone, working alongside Hallie in the kitchen of the eatery owned by Swedish immigrants Nora and Peter Ericson. Rance’s role in the community, however, is distinctly feminine. In a land where men wear guns and settle problems for themselves, he refuses to wear a gun and expects the law to settle disputes . . . somehow. Thus in the Ericsons’ restaurant, Rance wears an apron while washing dishes and occasionally waiting tables. (Obama also allowed himself to be photographed in an apron.) When Rance learns that Hallie can’t read, he takes on another stereotypically female role: schoolmarm.

When an apron-clad Rance brings Tom his dinner in the restaurant, Liberty trips him then mocks him. Tom is enraged. It is his steak, after all. Tom demands that Liberty pick it up. Tom is the toughest guy in town, the only one who is not afraid of Liberty. A gunfight almost ensues until Rance, still clad in an apron, picks up the steak for them, ranting about the absurdity of men killing one another over matters of pride. This too is an attitude more commonly associated with women. Ford clearly thinks that manliness is connected with a willingness to fight over matters of honor.

Rance begins to have some doubts, however, when it becomes clear that the local law enforcement, Marshal Appleyard, is a fat, effeminate coward. Devigne’s squeaky voice is well-employed, but Ford labors the point endlessly, to the point of cartoonishness.

When Rance allies with the local newspaper editor, funny drunk Dutton Peabody (Edmond O’Brien), to fight the cattle barons and appeal for statehood, Liberty is hired by the ranchers to intimidate the townspeople. At that point, Rance furtively buys a gun and sneaks off to practice shooting. Why the deception? Because he can’t really reconcile it with his self-image and the image he has established with the public.

There’s also a love triangle in the mix. Tom is in love with Hallie. Everybody sees it. But he hasn’t screwed up the courage to propose. It is his one failure of nerve as a man. When Rance enters the picture, Hallie begins by tending his wounds like a mother. Then she works with him in the kitchen like a sister (both in aprons). Then he schoolmarms her along with a brood of Mexican children. Rance is pretty much zilch as a man, certainly nobody Tom would regard as a rival. But when Hallie begs Tom to stop Rance from getting himself killed in a duel over honor, the big lug realizes that he is in danger of losing his girl.

When Rance (still wearing his apron) faces Liberty Valance, Liberty toys with him, shooting a jar first, then wounding his arm, then taunting him to pick up the gun again. Rance does so, takes aim, and shoots Liberty dead. Hallie rushes to tend Rance’s wounds. But Rance is no longer a child. He has faced death in a duel over honor. He’s a man now. When Tom sees them together, he knows that he has lost Hallie. He gets staggering drunk and burns his own house down in self-pity.

Rance Stoddard enjoyed some esteem for his good heart and his skills as a teacher and a lawyer. But his refusal to carry a gun put him in the category of women and children when it came to defending the community. However, when he shot Liberty Valance, he became a man and a hero. It also launched his political career.

But none of this sits well with Rance’s puritanical idealist streak. He feels that he bears the “mark of Cain” and is perhaps unworthy of public office. So Tom takes him aside and tells him a story. Tom was watching the confrontation with Liberty, and when Rance raised his gun to fire, Tom shot Liberty dead with a rifle. Tom is willing to take the guilt — and also the glory — to salve Rance’s morbid conscience. “It was cold-blooded murder,” says Tom. “But I can live with it.” It is telling that Rance can’t live with killing in self-defense.

I wonder, though, if Tom’s story is even true. Did it really happen, or did he make it up to spare Rance’s feelings? True or false, Tom is astonishingly generous. If the story is true, Tom saved Rance’s life and lost the woman he loved in the bargain. If the story is false, Tom is admitting to murder simply to make Rance feel better, perhaps because he hopes to promote Hallie’s happiness even after losing her.

This is an enormous risk for Tom. If Rance shot Liberty, it was self-defense. But if Tom killed Liberty, he could hang for it. For Tom’s sake, Rance is forced to keep the secret. Oddly enough, his conscience allows him to return to politics, where he enjoys an illustrious career: Governor, Senator, Ambassador to England. Granted, he no longer thinks his public esteem is based on killing, but shouldn’t he be bothered that it is based on a lie? Perhaps he can live with the lie by telling himself that he is doing good things for the people. But couldn’t he say the same thing about killing Liberty Valance?

The deeper truth that Rance evades is that, for civilization to come to the West, somebody needed to shoot Liberty Valance. It doesn’t really matter who. When Dutton Peabody nominates Rance to represent the territory in Washington, he explains how the West was won. First, it was held by merciless Indian savages. Then it was settled by cattlemen, whose law was the gun. The cattlemen did what was necessary, namely kill and subjugate the Indians. Then came the farmers and businessmen, who need fences and law and order. Liberty Valance is a hired gun of the cattle interests. His type was necessary to deal with the Indians. But now he has outlived his usefulness and stands in the way of progress. Progress requires a new kind of man: Ransom Stoddard, attorney at law. And isn’t it poetic that Rance Stoddard is the man who shot Liberty Valance?

The possibility that the story is false is supported by Ford’s frank exploration of noble and ignoble lies later in the movie. Although the newspaper editor has pried the story out of Rance by insisting on his “right to the truth,” once the tale is told, he burns his notes and tells Rance he will not print the truth. “This is the West, Sir,” he says, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” What he really means is when facts are replaced by legend, print the legend.

But why replace the truth with legend? What’s wrong with the truth? The superficial truth deals with who shot Liberty Valance: Tom or Rance? If Tom shot Liberty, he can’t be punished now because he’s dead. Rance, of course, kept the secret. Perhaps there would be legal consequences for that. But the real need for deception has to do with the deeper truth: somebody needed to shoot Liberty Valance so that civilization could come to the West, just as the Liberty Valances of the world were needed to shoot the Indians. This truth needs to be concealed because it does not sit well with liberalism.

Liberalism seeks to do away with force and fraud in human affairs. This is a noble aspiration shared by anti-liberal thinkers as well. Liberal theorists are famous for constructing accounts of how civil order can arise from the state of nature without force or fraud, by means of a social contract between rational agents. It is only because liberals think that political legitimacy depends on the immaculate conception of liberal order, without resort to force and fraud, that they are forced to print the legend. Liberalism does not banish force from politics, and especially from the foundation of political order. It merely banishes honesty about force.

Rance Stoddard is a brilliant and scathing portrait of liberalism. When Rance’s priggish, effeminate idealism clashes with the grim reality of the state of nature, Tom Doniphon needs to rescue him again and again. If Rance really shot Liberty Valance, it was only by discarding his initial belief that there is no difference between Liberty and Tom — and only by taking Tom’s advice to buy a gun. If Tom shot Liberty Valance, the repudiation of liberalism is even deeper, for Rance has the law on his side but isn’t up to the task of defeating Liberty, so Tom has to commit cold-blooded murder.

Liberalism, in short, depends on illiberal men and extralegal violence for its very survival. But, instead of questioning their own ideological premises, liberals simply lie about this fact. Ford doesn’t dispute the benefits of law and order. He just thinks they would be better secured by men who are more honest about the role of violence in founding and maintaining them.

This is an amazing message for a Hollywood film. I have no doubt that this is Ford’s intended meaning. Everything about this film, both its virtues and its flaws, is 100% John Ford. He was one of Hollywood’s most meticulous auteurs, a fact that is somewhat hidden by the formulaic quality of all his films. Ford started making movies in the silent era, when they were everyone’s entertainment, which meant that every film had to have something for everyone, including a love story and some crude comic relief, usually involving booze. Of course one could level the same sort of criticisms at Shakespeare.

I chalk the film’s flaws up to the self-indulgence of old age. Ford was pushing 70, and his hard-working, hard-drinking life was catching up with him. Perhaps we can credit the film’s virtues to another trait of old age: impatience, because time is short, which leads to greater frankness, even though it might ruffle some folks’ feathers.

I don’t want to spoil the movie’s brilliant and heartbreaking final scene, so I will leave you with these words. Since men like Liberty Valance need killing to create political order, nothing is too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance. It is a burning indictment of liberalism that such men lie unsung and unstoried in paupers’ graves.

The Unz Review [5], March 25, 2021

* * *

On Monday, April 12th, Counter-Currents will be extending special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

As an incentive to act now, everyone who joins the paywall between now and Monday, April 12th will receive a free paperback copy of Greg Johnson’s next book, The Year America Died.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: