Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 84

Greg Johnson Interviews Charles Krafft

Posted By

Charles Krafft

On

In

North American New Right

8,328 words

Editor’s note: This is a transcript of a Counter-Currents Radio episode [2] that originally aired January 17, 2014. We would like to thank Hyacinth Bouquet for this transcript.

Greg Johnson: I’m Greg Johnson. Welcome to Counter-Currents Radio. Our guest today is artist Charles Krafft. Charlie, welcome to the show!

Charles Krafft: Thank you. Good to be talking to you again, Greg.

GJ: Well, it’s good to be talking to you. You have had a really eventful 2013. Back at the beginning of the year, you were outed by a local alternative paper, the Stranger, in Seattle, as not just a revered porcelain artist who’s been exhibited all over the world, but also as Holocaust “denier” and as a “racist” and a “White Nationalist.” And that led to a firestorm in the media.

I’d like to talk about that today. Just recap it a little bit and talk about what’s happened since then. Because a lot of our listeners probably worry that someday they might be outed as a White Nationalist, for instance, and they worry about the consequences for them.

You have provided a really good example of somebody who was singled out in the media for attack. You stood up for yourself, and I’d like to find out how it’s all played out in nearly the one year that has passed since then.

CK: Where do you want to begin?

GJ: Well, let’s begin with the attack. What happened? Just recap it a bit.

CK: The story, in a nutshell, is that I had a kind of a stalker on my Facebook page, who was using pretty crude language, who people thought was a sock-puppet of mine. One of the persons that thought I had a sock-puppet with a foul mouth was a psychology teacher at a local college, who messaged me on Facebook. Her message was that she was surprised I hadn’t been outed as a “bigot” by the local art community. She mentioned this poster on my Facebook page, and I told her that it was not me and that, furthermore, I was not going to censor the poster because I didn’t like censorship — even if the poster was kind of using crude language. And I said, “I really don’t like censorship, at all.”

I also suggested that if she felt I should be outed, maybe she should be the one to do the outing. So, apparently, she did write a letter to the local art critic and outed me to the critic, who wrote to me and asked me what I thought about the Holocaust. I wrote that critic back and said, “Well, gee, I’m between a rock and a hard place. I’ve written one essay about the Holocaust, which I can send to you, if you’d like to look it over.” Which I did.

I told the critic that I didn’t want to be interviewed at that particular time about this. She was angling for some kind of a story, obviously. So, she wrote me back and said, “Fair enough, if you don’t want to pursue it.”

About eight months later I got an e-mail from her, and she said, “Whether or not you like it, or not, I have to write about you. I have some questions I’d like to ask you. You can answer them, or you can not answer them. Whether or not you do answer, or not answer, it’s not going to make any difference to me. I’m working on a story, and it’s coming out soon.”

I said, “Okay, fine. Send me the questions you want answered.” So, I got a series of questions, which I answered. And then this story came out while I was in India, attending the Kumbha Mela, which is a big Hindu religious festival that happens once every 12 years in Allahabad. I thought, from India, that this story would be a small, kind of gossipy, storm in a local teacup in Seattle, where I’ve lived all my life, and I know all the people here that are involved in the arts. Not all of them, but quite a number of them. I thought, well, you know, this will be interesting.

I knew about the Stranger, I knew a little bit about the way they work, and I expected the worst, and I did get it! But that story went viral. It got picked up all over the world. And as a result of it going out and getting seen and picked up, I started getting requests from the mainstream media for interviews and comments. I said “yes” to everybody that asked me for an interview, and I must have done about five or six of them.

Finally, I got a letter from an editor of the local Seattle Jewish newsletter here. She wanted to interview me. I drew the line. I finally said, “I’m just going to be giving you more rope to hang me, and nothing good has come of most of the interviews I’ve given. I’m going silent now.”

For a while there, I was an open book and saying “yes” to everybody. And then I finally just got tired of being interviewed, and so I quit doing it.

GJ: So, would you advise people who are in a similar situation simply not to give interviews at all?

CK: Well, I would advise them that they can give an interview, but if it’s with a mainstream media outlet, there’s no way that they’re going to be able to put themselves over well. The cards are stacked against you going in. So you might as well. If you say “yes” to it — like NPR for instance — the way it’s ultimately edited and presented will be probably a negative for you, if you’re a White Nationalist or a skeptic about the received history of the Holocaust.

GJ: I remember the Kurt Andersen interview with you, and there was stuff in there that seemed obviously taken out of context. One of the things that I always recommend to people who give audio interviews, or video interviews, is to let the interviewer know that you’re making your own reference copy of the interview, either audio or video.

I think that’s one of the ways we can try and keep these people honest. But if they just have the only copy of the tape, they will cut it up and shuffle it around any way they want. And, yeah, their tendency is to put things in the most negative possible light.

CK: Yes, and they do a lot with that bumper music that they use! That Kurt Andersen interview was 30 minutes of talk back and forth with him, and I think it only ended up as seven minutes on his program. Seven to ten minutes. And he made me look like I was insane. I walked right into a trap that he set for me. I re-listened to it recently, and I thought I did okay, but at the end, he had the upper hand.

GJ: Yeah, yeah, you’d have to be a fool not to have the upper hand if you’re the one who’s holding all the cards and gets to edit the thing.

CK: Yeah.

GJ: So, that’s the trouble with the mainstream media. They have all the cards. You give them the raw data. They fashion it into a rope to hang you with.

CK: Right.

GJ: We ran three articles about this at Counter-Currents. Do you have an estimate of how many articles ended up being published about this controversy?

CK: Well, I have a friend who is an artist that was following the controversy, and he claims that he counted 71 places where this story, and permutations of the story, appeared on the internet. In print, the only things that came out were the Stranger article, hard copy. And I got, believe it or not, the front page of the local Saturday edition of the Sunday paper here. Then when the Sunday edition came out, I was in the lifestyle section on the front page. Because the Sunday paper comes out a day early here, and they have two. One for Saturday and one for Sunday. It’s kind of an early Sunday edition and a late Sunday edition. And I was on the front page of the early Sunday edition.

So, just in print, only two places where it appeared. But a lot of blogs and websites picked up Jen Graves’ story and just repeated it, word-for-word. So, if indeed there were 71 instances where my name and this issue appeared, on a blog or on a website, I would say two-thirds of that were just repetitions of the original Stranger story.

GJ: You also made the Huffington Post year-end roundup. Tell us a bit about that.

CK: Well, the Huffington Post really made Jen Graves kind of famous, because they reprinted her Stranger story, and then two of their writers decided to comment on the story that she had written for the Stranger. So, I got actually three Huffington Post articles at the time. And then right before Christmas, they did a year-end roundup of the 12 biggest art fails of 2013, and I was number six on their list of the art fails.

I guess they were being kind of cheeky. That was the point of listing these art fails.

GJ: Snarky.

CK: Yes, snarky.

GJ: Yes. So, what company were you in amongst these art fails? There were some pretty well-known artists and dealers who were mentioned there. It’s kind of not bad publicity, in a sense, when you look at the people that you were in the company of.

CK: The one I remember most was the Bolshoi Ballet.

GJ: Exactly!

CK: Apparently, they put on some performance that everybody hated. But, anyway, there I am, with the Bolshoi Ballet. I can’t remember the other people I was in the company of.

GJ: One huge Armenian-American art dealer, I forget his name, that was mentioned in there because one of his exhibits was not PC enough, or something like that. I thought, “Wow! You’re in august company. You have all of these people who have fallen afoul of the politically correct.”

CK: Was it Tony Shafrazi?

GJ: You know, I don’t know. I can’t remember the name. But anyway, I didn’t really think it amounted to bad publicity in the end.

CK: Oh, I was absolutely thrilled to be remembered and then stuck in this august company, you know?

GJ: Exactly. So, tell us what happened to your exhibitions and speaking engagements and things like this, after the story started circulating.

CK: Well the speaking engagements on college campuses had sort of dropped off. At one particular point, a few years ago, I was getting invitations to give slide lectures to graduate students in the art departments of various art schools and universities around the country. That was a part of my annual income. I’d get an honorarium and probably a dinner out of the deal with the head of the department. And then I’d give my lecture. Then I’d visit the graduate students and do these personal one-on-one conversations with them about their work and what they might expect once they get done with school.

I learned from a kid in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who had wanted me to come to his college to talk that I was on a list of proscribed intellectuals that were to be avoided by college department heads who were looking for speakers and visitors. I can’t remember the acronym of the name of this organization, but there is apparently a group of academics who advise other academics on who is “good” and who is “bad” for college speaking engagements. I’m now on some sort of a blacklist, I guess. He told me that his department head had brought him a sheaf of printouts about me that had been provided by this academic organization when they did a search on me.

So, I can’t say that anything was canceled, because I hadn’t had any invitations last year to visit colleges. But I did learn about being put on this list.

And what was the other half of that question?

GJ: What happened to your exhibitions?

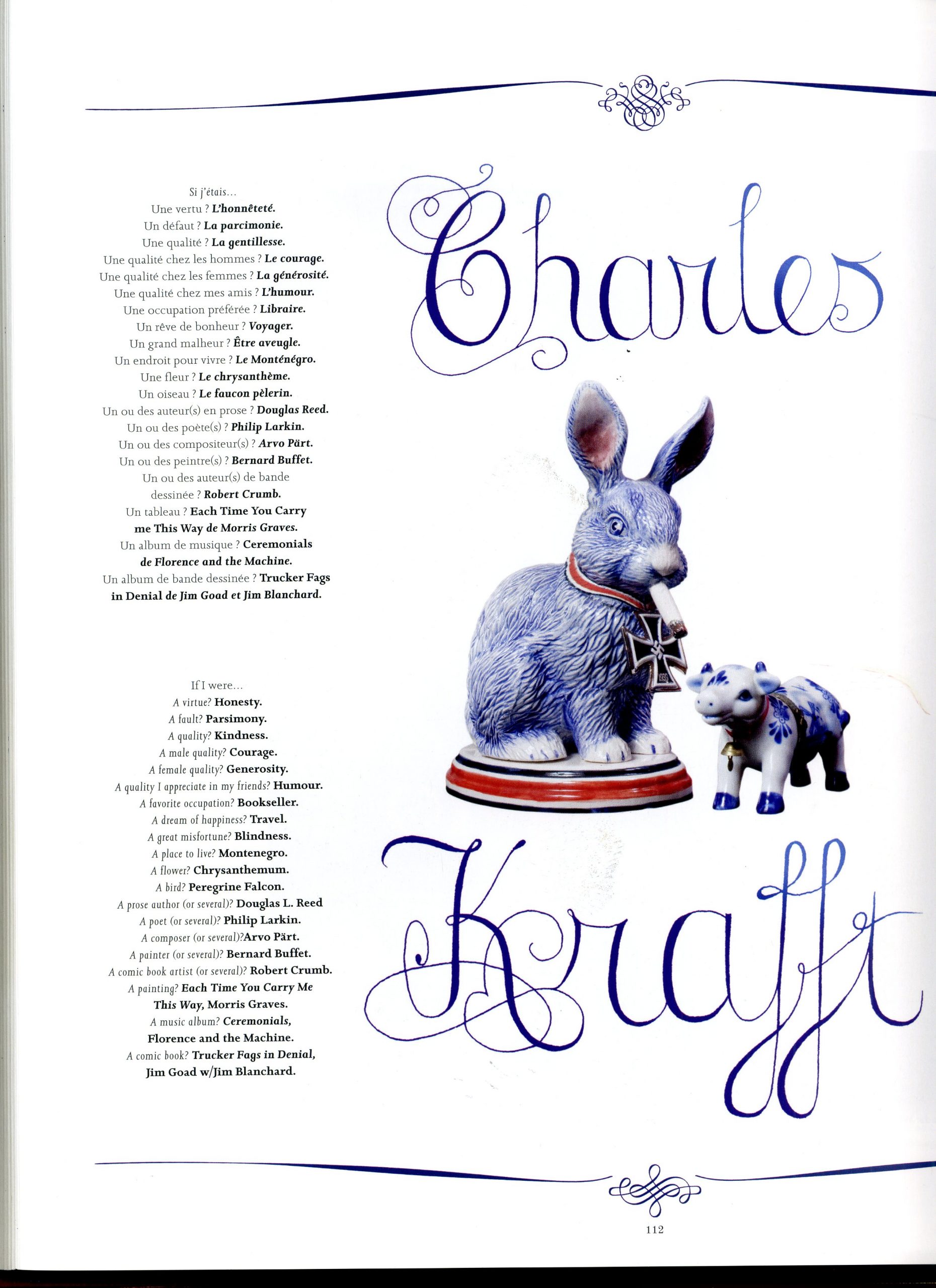

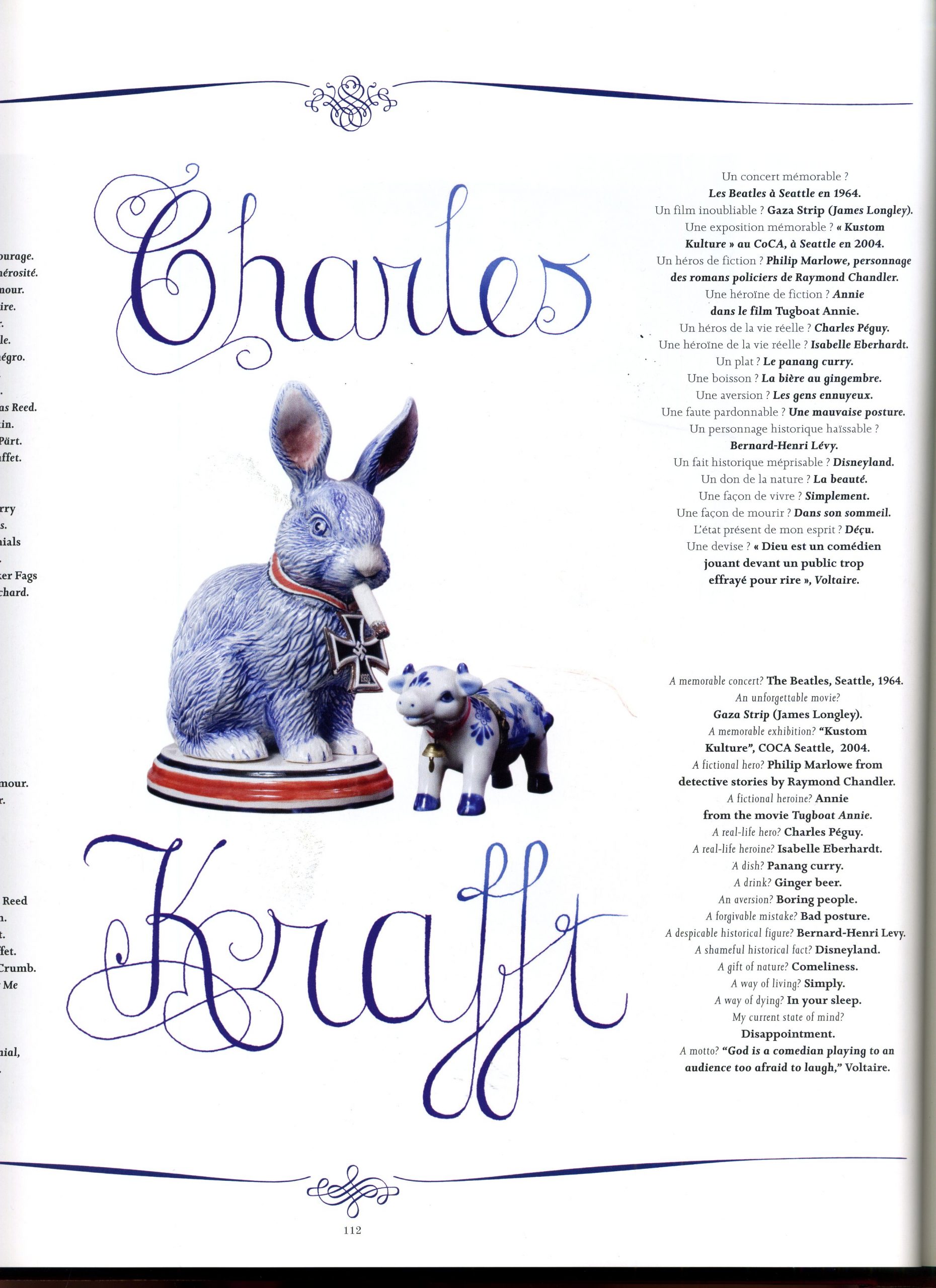

CK: Oh, yeah. Well, I was in a show in Paris. It was about urban art and lowbrow art. In Europe they call lowbrow art “street art” now. This is a sort of the street art show. I was asked to do what they call a Proust Questionnaire, which you used to, you often see in the back of Vanity Fair magazine when they ask a celebrity a bunch of questions about themselves. Are you familiar with Proust Questionnaires?

GJ: Yes.

CK: Well, for those who aren’t, it’s just they ask you who’s the most inspirational person in your life and what scares you the most and what color is your favorite color. These kinds of little questions are supposed to help people get a fix on your personality.

They sent me this Proust Questionnaire, which was going to be published in the catalog along with my biographical information. Every artist in the exhibition got [a catalog], I assume. I never did get my show catalog, by the way. They never sent it to me. This was after my work was taken out of the show.

Some Leftist, Antifa blog in Paris picked up the story, and published their comments about me, which caused the people that run the venue where the show was being presented to ask the curators to remove my work. When I got the e-mail from them about this, I was livid! I wrote a little statement back to them, and I had no more communication about the issue with them until I received my work back in the mail.

I never got to read my Proust Questionnaire, which I had to revise. They had a problem with the first one I submitted. I never got the catalog sent to me. That was part of the deal. I was going to get a free catalog, a contributor’s catalog.

And then I never heard another word again from these two editors of an art magazine in Paris called Hey! I just assumed because they’re French they are . . . Obviously they are upset with me, I guess. I didn’t even want to deal with them anymore. So, I didn’t write back.

I sent them a statement about cultural Marxism, and not wanting to march in Gramscian lockstep with the other artists in the show. It was an angry little thing, a little statement.

So, yeah, I got censored in France, where they have the Gayssot Law, which is a law about Holocaust denial, that they mentioned. The curators said it’s illegal for us to . . . I guess they were telling me it’s guilt by association. If we have a Holocaust denier in our show, we are somehow liable, too, for this. They brought up this Gayssot Law, as part of the reason why they censored me.

GJ: I think you also mentioned that various museums where your work is displayed have started putting up warning labels, sort of like parental guidance warnings.

CK: At the Sacramento museum, somebody that I know took a picture with their cell phone of the new identification tag alongside a piece of mine that was donated to their collection. There’s a qualifier about me being recently outed as a Holocaust denier. I don’t know why they had to put that on this identification card. Because of what? Their display has nothing to do with the Holocaust. But there I am. It’s Charles Krafft. They mention this NPR business. I was on NPR. So, that’s the only instance I know where they’re starting to put warning labels on my art.

GJ: Well maybe you should just incorporate warning labels as a kind of design motif in your future work. Why not get out ahead of this — own it?

CK: Well, you know that I can do just about anything I want in the way of épater la bourgeoisie. The cat’s out of the bag! What have I got to lose?

GJ: Right, right. So, tell us a little bit about the positive and the negative consequences of all of this for you. Tell us first a bit about some of the personal fallout. I understand that there was some relationship drama. Family drama, things like that.

CK: Yes, there’s some family drama, which I won’t go into too really seriously. Relationship drama, I’ll probably steer clear of that, too. I did get some letters from people, from old friends. And they were lecturing me on my morality and calling into question my sense of good and my sense of decency. They think that not believing the received history of the Holocaust is indecent. So, they let me know how indecent they felt that was. And one of them had CC’d his whole family. He’s got grown children, so each of the children got this letter, this e-mail, that he sent to me expressing his disappointment in my moral failings. I didn’t get a Christmas card from those people this year, I noticed. So, there’s that.

Then an old teacher that I had been corresponding with over the last 40 years, whom I had as my freshman English teacher in college, wrote me a letter and said we could no longer be friends — as a result of what he’d read about me in the newspapers. I don’t know how to describe this letter other than that it was a rather final write-off of this friendship, this correspondence and ongoing friendship that we’d had since 1966, when I first met him.

GJ: That’s amazing. Did you make any new friends?

CK: Yeah, well, I made a lot of new friends — not a lot, because there’s not a lot of us — but within the, let’s call it the White Nationalist movement, people actually sat down at their computers, most of them, found out where they could contact me, and sent me letters of support, e-mails that said, “I’m glad that you’re standing up for yourself and not letting these people get you down.”

I appreciated that. I got a couple of letters, believe it or not, from readers of the local newspaper, who put stamps on envelopes and sent me letters of support. I don’t know who these guys are, but they took the time to let me know they felt I’d been kind of smeared, and they didn’t like it. They believed that I should be allowed to say whatever I felt about anything. I mean, we have a First Amendment in the United States.

These letters and e-mails of support sort of drifted in. I appreciated the time that people actually took to sit down and address me personally. In this day and age when somebody does that, it’s meaningful.

GJ: Oh, definitely! Very few people write letters anymore so when they do that, it’s a sign of something.

CK: Yes, it really is. It’s a sign of commitment to an old-fashioned way of expressing your opinion and support of a person. So, there was that. And then I got a big spike in Facebook friend requests from people that are sort of in our camp. And so I approved all of those. I engaged in conversations with other artists, some of whom are sort of out-of-the-closet on their politics. And then others, who sent me messages that they regretted that they couldn’t come out of the closet about how they really felt about things, because of their professional careers, and their academic careers. A lot of college kids, they seemed to be really worried, if somebody finds out what they really think about things. As they’re going through school getting brainwashed by these teachers of theirs.

So, that was an upshot of this. I think that the positive actually outweighed the negative, to tell you the truth. I mean, there was a lot of negative ink spilled about me, but on a personal level I got more positive responses than I did negative ones.

GJ: Well that’s great. Was this personally difficult for you? I imagine you kind of dreaded looking at your e-mails for a while.

CK: Yes, I did. I dreaded it. What I did was, there’s a Google search option that you can use for Google to harvest anything that comes through them about a subject or a person that you want to know more about. Or a news item. I put my name in the Google search box for any articles about Charles Krafft. And every day there was a new one! I’d go, “Oh my God.” I’d go there, and I’d look. There’s always the same kind of smear.

Yeah, I did dread the Google search notifications, that there had been another article somewhere about me, because I’d have to go and read it. What happens is, it’s like a circle-jerk. And you find this when you’re reading books, too. Especially history books. People will use whatever people have said and repeat a falsehood. It’s almost impossible to correct. I could have gone to the comment sections in the places where these articles appeared and corrected them on certain things, but I just finally felt it was a waste of time. There was so much that was so wrong, I couldn’t spend the rest of my day just trying to put out fires.

So, I just let it all slide, except for the Vice interview. There was a Vice London guy, called me up on the telephone trans-Atlantically and wanted an interview. Which I gave to him. And then once he got it in the pipeline and posted on Vice, I really didn’t like it. He put words into my mouth, and he used English colloquialisms that I don’t use and made me look like an awful person. So, I did actually go in and make a comment at that particular site about the way he had managed to mangle his story. But that was it. I steered clear of trying to defend myself in these places. It’s just a waste of time.

GJ: Right, right. The number of people who can generate nonsense about you is pretty much infinite, compared to your ability to answer all of this nonsense.

CK: Yeah, you just can’t answer it all. Like I said, to get back to this thing about . . . One person will say one thing, and then the next hack journalist, or hack blogger, will pick up that thing and repeat it. So, it gets repeated over, and over, and over again. Sometimes they’ll add their two cents to this repetition until it’s nothing like what it was. It’s like that thing where you play a game where you whisper something into somebody’s ear, and they’re supposed to whisper it to the next person, who whispers it to the next person. Then finally, at the end of the game, what started out as the secret turns out to be something completely else.

GJ: There’s a story about the UN, where the English phrase, “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,” was translated by the translation team into all these different languages. And when it got translated back into English, it was: “The wine is good, but the meat is rotten.”

CK: Yeah.

GJ: So, what are some of the professional consequences of this? Has this hurt you economically?

CK: Well, no, it hasn’t hurt me economically. However, I was working on a commission when the story broke, for a local guy, who then refused to pay me for what I’d made for him. He had requested three objects, which I had gone ahead and done for him. I wouldn’t have done them otherwise, in the manner in which he wanted them. So, I call that a commission. He said, “Somebody’s just told me about some press that you’ve gotten recently, and I’d like to ask you some questions.” I said, “Well fine, but let’s keep this about business. We have a business relationship here. I don’t want to get into philosophy and religion and politics. Let’s stay away from it.” I never heard back from him, and he never came to pay me for what I’d made for him. It was really a cold kind of dismissal.

GJ: Did you deliver the stuff to him? Or did you . . .

CK: No, no, no! I said, “Your stuff is ready.” I had taken photographs of it, and then I never heard again from him. This is after he said he wanted to ask me some questions, and I said, “Yes, I’ll answer them. But I don’t want to. Our relationship is not about religion or politics. Ours is about business.” And then I never heard back again from him. And he never paid me for what I did.

GJ: Did you manage to sell it to somebody else?

CK: Yes, I did. I turned around immediately, and I sold the three pieces I made for him to a collector in France.

GJ: Well, great. Great! So, that’s a wash.

CK: Yes. But the way the guy did it, it really was impolite. And unprofessional. And I disliked it so much I thought I’d write him a note about how I felt. Then, I thought, “Well no.” I don’t want to let him know that I even think this about him. I didn’t want to waste any more time with this fool. So, I didn’t send him a letter. He should have said, “Well, I can’t go on with your politics.” Or “I can’t have this stuff in my home now that you’ve been blackballed by the community.” He just quit communicating.

GJ: So, overall though, can you say that in 2013 your business, your purely business aspect of your artwork, was up or down, or pretty much the same?

CK: It was pretty much the same, with a little bit of a spike.

GJ: That’s great. Did you get new commissions from people who were sympathetic?

CK: Yes, I did. I got commissions from people that felt that it would be a way to support me, and they were sympathetic. They enjoyed my art, and they said, “Now is the time I’d like to buy some.” They made a kind of a commitment as a result of the press I got.

GJ: That’s great. That’s really great.

CK: Yeah. I’ve appreciated that. We’re talking here about four or five people that did this. Actually stepped up to the plate and bought some art from me as a result of the interview that I did with you earlier. You know, the two interviews around that time?

GJ: Right.

CK: They’d heard them!

GJ: That’s great. That’s great. The enemy tries to destroy people by destroying their livelihoods. And it’s important to know that when you’re an independent businessman, you are somewhat immune to that. You might lose some customers, but other people, if they hear about this and get incensed by the injustice, are going to step up and try and make sure that they can’t hurt you. That kind of solidarity within our sphere is a really positive sign, I think.

CK: I do too, and I can’t thank these people enough for helping me out.

GJ: So, Charlie, tell me about the artists. Obviously, you don’t want to name names. But tell me about some of the artists that you have been contacted by. And has this spawned any new artistic collaborations or projects?

CK: I think it might be best for me not to mention names of artists, but I got contacted by White Rabbit Radio.

GJ: Right.

CK: And, as a result of that, I’m sort of working with the artist that does the graphics for Horus the Avenger. He’s sort of the in-house artist there. He lives in Kentucky. He and I are working on a project now, together.

Horus, himself, he bought a piece from me. He’s one of these people that heard the interview. Actually wanted to purchase something for his collection. Did so, and now I’m talking to him about another piece that I’m making especially for him.

Those guys are fully committed members of this White Nationalist community, and they’re very supportive. So, I appreciate it. And I’m glad I’m in touch with them, because it’s just nice to have other people that are art makers and culture makers to talk to about business. We’re tradesmen! I’m always looking for other people that are in the same kind of trade I’m in, just to talk about it. I like what I do, and if they like what they do, it’s fun to compare notes. And ideas.

GJ: One of the things that I really want to try and encourage, in whatever small way I can with Counter-Currents, is the kind of artistic subculture that existed on the Right in the first half of the 20th century. There was a lot of excitement! There were a lot of great artists, and poets, who were involved with this. And there were all these amazing manifestos from the futurists, and the Vorticists, people like Marinetti, Wyndham Lewis. I would like to see more of that in the future, in the 21st century.

Do you think anything like that sort of artistic subculture or movement might be helped along by some of this exposure that you’ve gotten and some of the networking that has taken place since then?

CK: Yes. I think eventually something will be done, because I remember zines coming out, before even the age of the computer. Were you around? Did you ever subscribe to any of these zines that people were self-publishing, magazines?

GJ: Well, I was sort of late to all of this, so that was more like mid-1990s.

CK: Yeah.

GJ: And it kind of died with the internet. I remember reading copies after it had stopped publishing. I remember reading Answer Me, the Jim Goad zine. That was pretty amazing stuff.

CK: Yeah, that was. Well, that’s exactly what I’m leading up to. Goad’s magazine, Answer Me, came out of the zine culture. It was pretty nicely published, and it ended up on magazine racks in places like Tower Records.

Well, I recall even back then, music zines having discussions about fascism and occultism. And music and fascism. And occultism and music. In this mix, you see, of music, occultism, and fascism, and National Socialism. That’s where I started learning about these artists from Europe, who had been completely swept under the carpet after 1945.

I’d never heard of any of these people. Ernst Jünger, for example. How would I have ever found out about Ernst Jünger if I hadn’t been reading neo-folk zines, you know?

GJ: Right.

CK: There’s a list of names of people that we could go over that I discovered through this little self-publishing world, which was transposed into internet blogging where you can go and find out about it. I think, yeah, it would be nice if something like Answer Me, with that much of an audience, a national audience, kind of like a mainstream newsstand audience. Or a mainstream bookstore audience. I think that we might build up a critical mass, eventually.

We could have a magazine like that. That’s the way Juxtapoz started. It was a reaction against these academic art magazines that everybody was just bored to tears with. Art in America, and some of these other highbrow art magazines, initiated Juxtapoz. And then Juxtapoz led to Hi-Fructose magazine, and it opened up a whole new window into another area of art-making that the mainstream art magazines were completely clueless about.

I think if there’s enough people with time to sit down and put together, to curate their interests, and to write about their interests, we might be able to get something going. An anthology. It would be probably kind of a pioneering thing, too. Because I tend to think that more and more people that read books and think about things more seriously than most, are starting to see through what we’re being presented by the mainstream media, in the way of dialogue. God, these news stories, and discussions about culture and politics. A lot of people can see right through it.

A lot of people quit watching television, I know. The New York Times . . . People are no longer grabbing the Sunday Times — they’d spend the Sunday in bed with it — because they know there’s a lot of BS going on there.

GJ: I think the system is sort of losing its grip on people’s minds. I don’t think a lot of people are willing to affirm an alternative yet, but they do know down deep inside, that what they’re getting is a thinner and thinner PC gruel — and it’s not healthy for them.

CK: Yes, and I think a lot of the cultural mavens are being exposed as having feet of clay. Noam Chomsky, for example, people are beginning to think, “Well yes, he’s a gatekeeper.” Smart people are starting to figure out who has been precision placed to keep us sort of in a mental box about issues. I see people waking up all over the net.

But, then again, I spend my time on the internet in all these oddball places. I’m way off in the fringe looking for more and more eccentric art and commentary.

I’m not a good example of a person that is balanced anymore, because I’ve swung way, way, way over to the fringe. Center Leftist, center Rightist — I’m not interested anymore. I’m interested in extremism, and I’m not ashamed to say it. That’s where I find the most excitement in writing and in art-making.

GJ: Well, that’s where culture is created. It’s in the extremes. No culture is created in the center. Unless it’s junk culture. Lawrence Welk kitsch, and things like that.

Your Facebook feed, I might add, is a great source for me. In my conversations with you over the years — you can attest to this — I always carry around a notebook, and I’m always jotting down names of artists and museums and books and things like that. Because you are just indefatigable in turning up interesting new stuff. Every time I talk to you, the world gets bigger. So, I really appreciate that. Your Facebook feed gives that to me on a daily basis.

CK: Oh well thanks! On my Facebook feed, I’m essentially just sharing my own discoveries. It’s not like I know all this already. I spend time sort of exploring, and then when I find something interesting, I hurry up and want to share it. That’s the way I’ve been all my life. When something excites me, my immediate reaction is to tap somebody on the shoulder next to me and say, “Hey, get a load of this! Isn’t this interesting?”

I’ve always been kind of eager to just share what I’ve found out about this and that. That’s why it’s hard for me to keep a secret. It’s hard for me to fly below the radar.

GJ: Well it’s really amusing. When they finally outed you in 2013, I did a search for you on the internet to get background to do the interview with you and the articles that I wrote. I remember in 2005, in 2008 — I think those were the years — you were given a reward for writing an essay on some Holocaust hoax. You did an interview on this stuff. This stuff was floating around out there a long, long time ago. You weren’t trying to keep it secret, really. But it took Jen Graves eight years or so to finally catch up with this and start jumping up and down and pointing at the witch! I thought “it’s not a well-kept secret.”

CK: No. It wasn’t.

GJ: You were hidden out there in plain view.

CK: Last night I was reading something about Mircea Eliade. Somebody was writing a book about Portugal during the war, and I knew that Eliade had been to Portugal. So, I did this search on Eliade and Portugal. I landed on this blog. It’s called, “Politics and Metaphysics.” There was an article there on Eliade. I read this thing. And then, I went down to the comment section. I’m reading the comments, and I’m totally intrigued by the whole thing, and then I came to one of my own comments that I’d left there in 2009! I didn’t even remember reading the article or leaving the comment. And you know, it was a pretty good comment. I was really surprised . . . surprised myself. I said, “Geez, you’ve been here before and forgot all about it.”

GJ: That has happened to me. I’ve used so many pen names over the years. I remember doing a Google search on something, and I clicked it and started reading, and thought, “This is really good!” And then I suddenly realized, “Oh, I wrote this!”

CK: I wrote this! Yeah, that’s happened to me.

GJ: Well, Charlie, I want to just make a promise here, or an offer. I’ve got a full plate at Counter-Currents. But I would be willing to publish something that would be like an annual, or a zine, or whatever, if it would be a forum for people who are artists today, who want to make statements, and do analyses, and issue manifestoes. And also, a historical study of great artists of the past, if that would in any way contribute to the fertilization of a New Right artistic subculture.

I think that would be a tremendous contribution. It’s one of the things I want to do. I don’t know what form it would take. I would probably like it to be sort of a larger coffee table-sized thing, or like a magazine-sized thing. One of these things like these Hi-Fructose volumes, and other volumes like that. I have a lot of those.

Anyway, if there are people listening who are into this sort of thing, and if you’re interested in something like this, if you want to edit or curate a project like this, Counter-Currents will make it happen.

CK: The seminal books that I remember that actually had an impact on me, from the 1990s, were little anthologies. One of them was Apocalypse Culture. Do you remember seeing that?

GJ: Oh, yes. Those had a huge influence on me.

CK: He did a follow-up, about a decade later, Apocalypse Culture II. Just that little collection of weirdness that Adam Parfrey put between covers, it really had an impact on a lot of people, as did those RE/Search anthologies that were coming out of San Francisco on strange music and strange film and neo-primitivism and tattooing and piercings, that kind of thing.

GJ: Right.

CK: And interviews with oddballs, that they conducted there. These fringe characters that they’d unearth and get to talk for the first time to another generation of people. Esquivel, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of him?

GJ: Oh, yeah.

CK: Or Korla Pandit, an old organ player who’d go around the country in the 1950s and play the organ. In a turban! They go find these crazy guys that have been sort of celebrities in their day, but time had passed them over. Then, put them between covers and they became cool again, all of a sudden. Martin Denney, the Exotica stuff . . .

GJ: Right.

CK: Well, if we could somehow package a collection of interviews, essays, and photographs, and art pieces, that would relate to what we’re interested in, I think we might be able to make some sort of a dent, you know. Maybe in whatever is on the shelf next to the kids in the college dormitories. That’s where I’d like to see it.

GJ: Exactly. Get something out there that’s just mind-expanding and fertilizing for the imagination. I really do have to give Adam Parfrey a lot of credit for the Apocalypse Culture volumes, because they really did have that effect. Some of the stuff he published was so funny that I threw my back out laughing at it.

CK: Well, he’s still provoking people with his publications. David Cole is coming out with a book in the spring. It’s called Republican Party Animal.

GJ: Okay.

CK: I don’t know if you about it. . .

GJ: Oh, I know about David Cole, yes. That sounds like a really . . . Is this a Feral House publication?

CK: Yes. David Cole is going to talk about himself and his career, so I’m looking forward to hearing all about that.

GJ: I guess the title Republican Party Reptile was already taken by P. J. O’Rourke.

CK: Oh, really? I’m really interested to find out who in Hollywood is a Republican, by the way.

GJ: That would be a really interesting question, although the Republicans are so useless anyway. It almost doesn’t matter.

CK: Yes, just anybody there that’s a reactionary to the usual Hollywood Leftist agenda.

GJ: So, let’s sum up, Charlie. This has been a really enjoyable conversation. If somebody is out there in Radioland who’s thinking of taking the plunge, and becoming a little more open about his political views and being an explicit White Nationalist, what advice would you give him?

CK: Run that by me again?

GJ: Based on your experience over the last nearly one year, if somebody is out there who is thinking of becoming more open about his political activism, under his own name — or if somebody out there, who doesn’t want the publicity is about to get the bomb dropped on him by some other alternative weekly — can you give those people a little bit of advice about how to handle it? How you’ve handled it? And is it so bad?

CK: You’re going to have to ask yourself how much time do you want to waste talking to idiots. Because you’re going to get approached by people that are not only upset with your views, they think that they are immoral and out of line. But they’re probably not as well-read as you, or aware of how you arrived at your opinions.

When they come, you’ve got to remember that they’re not as well-versed in the subject as you are. You have to ask yourself, how much time do you want to spend trying to educate these people, who are there to do you harm anyway. That’s one thing I’d like to get across.

The second thing is, it’s going to blow over if it’s a big storm. It only lasts a while, because they have to get on other news. And you’re going to be yesterday’s fish wrap soon enough.

Friends and family: you’re going to have to be probably pretty strong in your commitment to your beliefs, because you don’t want to hurt people’s feelings that are close to you, and they do get hurt by the peer pressure that they get. This guilt by association trip that gets laid on anybody that is close to you that is open to attack.

The social sphere is the worst. Professionally, if you’re self-employed, I wouldn’t waste too much time about losing your job, really. If you work in a corporate office kind of context, there’s human resources, those people are deadly. You’re going to have to worry about that, probably. It might even be a good idea just to keep it under your hat, what you think, if you’re in the corporate sphere.

I don’t know what else to say, other than you can’t turn back once you’ve amassed a certain amount of information about something, and you know that what you’ve learned is probably the truth. How can you just go back after you’ve come into more truth than you had before? You’re just going to have to live with it, and if it gets really tough you can read about these other people that had a harder time than you did.

For God’s sake, back in the 1950s and the 1940s, some of the people that were talking about the stuff that we’re talking about were hounded out of their jobs. Some of them were brought to trial. We’re not talking about the blacklisting, either. We’re talking about the people on the other side of the fence: anti-Semitic preachers and anti-integrationists in the South. Intellectuals. People that were actually college-educated, non-civil rights participants and activists who spoke up were pilloried. They probably had a lot tougher time than I ever had. So, when you do get in this position, which is scary at first, just remember that you’re not the only one that it’s happened to, and you’re not going to be hung, for God’s sake. We have a little bit more leeway in America with our First Amendment rights than they do in Europe, so it’s not going to be as bad.

The social thing is the worst. When you have friends that disavow themselves from you, or the gossip starts up and some of it gets back to you, that can be kind of hurtful. Be prepared for getting your feelings hurt.

GJ: Overall, though, do you have any regrets over this? Or do you think that your life is, on balance, better or worse than it was a year ago?

CK: I think my life is better than it was a year ago. I was never really trying to conceal anything, as you noticed when you went back to check on me. The cultural Marxist gatekeepers of the community here in Seattle, we’re very liberal here. This newspaper is extremely liberal, and they needed to sell papers. They’ve learned that they can sell more papers when they generate a scandal.

After they got done with me, they went after a florist in town who had refused to sell flowers to a gay couple, for a gay wedding. That was the next big story that they wrote up for the rest of the month. They needed a sacrificial goat. And they chose me, and that’s that.

I knew who I was up against, and there really wasn’t too much I could do about it. It was kind of revealing to look at. I generated that article here, about 350 comments, from people that are in the arts, and I couldn’t believe how thick some of these folks are! I mean, they’re supposed to be educated. They’re supposed to be curious. And they’re supposed to be talented. And God are they stupid! I knew that Joe Six-pack was kind of thick, with his preoccupation with Saturday afternoon professional sports and all that. But I had no idea the extent of the retardation of some of these people here that are in the arts. It was amazing: what they think, and to see some of these guys come out swinging. It was just really entertaining.

GJ: There is nothing more vile and absurd than these vulgar, middlebrow, pseudo-intellectuals.

CK: Oh, God.

GJ: They are really, really thick. Thick as two short planks. And so full of themselves, that’s the other thing. Not only are they ignorant, but they sling that word around at us all the time. “Oh, you’re just ignorant!”

CK: Yeah!

GJ: “This is ignorance!” It’s just laughable! These people have never thought original thoughts in their lives. Have never ready anything outside the New York Times bestseller List, or beyond their college syllabi. And they have the face to accuse us, without missing a beat, of ignorance. They’ve been programmed that way.

CK: Ignorance, and bigotry, and . . .

GJ: Prejudice.

CK: And prejudice, yes. They called me a cranky white guy chasing immigrants off my lawn with a golf club!

GJ: Charlie, this has been a great, great interview. Any last words before we wrap up?

CK: I don’t have any last words other than, back to this idea of putting together some kind of a publication, we should ask the people that are interested. They can do it under a pseudonym, if they’d like to, and maybe we could have them get in touch with either you or me.

GJ: Exactly.

CK: Let’s just put the word out that if you’ve got something you want to share, and you think we might be able to use it in this context. Let’s just say we’re going to shoot for a one-issue anthology, for beginners. Let’s not say it’s going to be anything other than that, really. To go ahead and let us know what it is you’d like to share. And then we’ll look it over, and we’ll get back to you. Does that sound reasonable?

GJ: Yes.

CK: Because I’d like to do this too. I think it would be fun to have an anthology of writing on contemporary culture coming from our position, instead of this Marxist position.

GJ: Alright, well, I can hardly wait to have you back for another episode of Counter-Currents Radio. So, thank you, Charles Krafft.

CK: Well, thank you for having me again, Greg. Thanks for being a good explicator the last time around, when I was in such deep doo-doo. You were the only one that really — you and Carolyn Yeager, believe it or not — gave me a platform. Everything else was pretty negative. Anyway, I’d like to thank you for letting me be on the program.

GJ: All right. Well this, I hope, is just one of many, many more appearances. So, take care.

CK: Okay, thank you.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [6].

Don’t forget to sign up [7] for the weekly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.