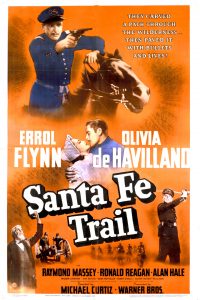

Santa Fe Trail

Posted By Steven Clark On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledSo they want to ban Gone With the Wind? Pity, because a movie they would really like to strangle is Santa Fe Trail. Made in 1940, Santa Fe Trail is an Errol Flynn/Olivia de Havilland Western with lots of action and romance that discusses slavery and the Southern point of view in rational terms.

Errol Flynn plays Jeb Stuart, and Ronald Reagan plays George Custer. They are classmates at West Point in 1854 (both attended West Point, but not in the same class), and are ready for graduation. The only canker is cadet Rader (a surly Van Heflin), an abolitionist whose open distribution of abolitionist pamphlets leads to a fight between him and Stuart, who argues that “the South will solve the problem in its own time and way.”

They’re hauled before Superintendent Robert E. Lee (a majestic Moroni Olsen, and yes, Lee was Superintendent). Olsen lets Stuart go, but assures him he’ll get a dangerous assignment after graduation as punishment. (For Errol Flynn characters, though, “danger” is code for derring-do.) Lee dismisses Rader for bringing politics to the academy. (True: cadets were forbidden any kind of political discussion or reading.)

Rader vows to get even and make sure the South gets what it deserves.

Graduation is presided over by Jefferson Davis as Secretary of War (true; he was), and Stuart and Custer get into an ongoing rivalry over Kit (Olivia de Havilland), a feisty girl from Kansas, the dangerous assignment where Stuart and Custer have been posted. Kansas is trying to get a railroad through, but can’t because of struggles between pro- and anti-slave factions, the latter led by John Brown (a frightening and almost Biblical Raymond Massey).

The historic railroad was halted by slavery and anti-slavery forces, but not because of actual border warfare. There was no railroad in Kansas or Missouri at the time. There were two railroad plans proposed: one going from Chicago to San Francisco, the other from New Orleans to Los Angeles, a sort of Iron Horse Route 66. The latter was favored by the South, the former by the North. Expansion stopped until the sectional struggle was resolved, so the struggle in the film is a simplified version.

Brown has just slaughtered pro-slavers in Pottawatomie, and when a shipment of “Bibles” (actually rifles) is intercepted by Stuart, the fighting starts.

Rader from West Point has joined forces with Brown, and although checked by Stuart, both are formidable adversaries. After the cavalry shuts Brown down, everyone returns East, where Stuart’s romancing of Kit is interrupted as Brown, financed by the Secret Six, a group of northern abolitionists (true), seizes Harper’s Ferry and uses its arsenal to lead a slave insurrection (very true).

Brown and his men’s total surprise attack allowed them to seize the arsenal. They were ready to head into the hills and draw in escaped slaves, but in a historical curiosity, Brown stopped. In the movie, this is because of Rader’s conniving, but historically, Brown stalled and became inactive shortly after achieving his goal. Sort of like a gang completing the perfect bank robbery and, instead of making their getaway, going across the street for a celebratory dinner.

Lee mobilizes the Army to stop Brown. The rousing battle in the film wasn’t quite so in real life, lacking mass charges, artillery, and dozens of casualties. Lee led a company of Marines, and various Virginia militia units provided back-up, but Stuart was there and did deliver a surrender ultimatum to Brown.

[2]

[2]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [3]

Also curious (not shown in the movie) is that when the shooting started, the first man shot by Brown’s men wasn’t a slaver or evil racist, but a curious baggageman at the railroad station, a free black liked by everyone.

Brown is defeated and hanged, but not before he prophesies a “holy, bloody war” to end slavery. Stuart and Kit are happily wed on a train puffing away to Kansas. All is well . . . for now. Almost true. Stuart did marry a girl from Kansas, although she was an army brat with her parents on her father’s latest posting.

This movie was always a childhood favorite of mine, and has lots of action, comic relief, high spirits, and the usual Errol Flynn swashbuckling. Santa Fe Trail‘s historical portrayal of the slavery argument is convincing, but the temper of the film is decidedly pro-South. It must be emphasized that this was the former establishment viewpoint: slavery was wrong and needed to be resolved, but America had no place or support for armed insurrection against the government to end it.

Brown is depicted as a fanatic willing to see his sons die for this cause, and Massey plays him like an evil Moses, but not in a one-dimensional way. Massey’s Brown commands strength and respect. Exasperated, he asks Stuart: when will the South end slavery? The answer seems to be “only by violence.”

Stuart, Lee, and Davis were Americans who have respected places in the government. In essence, the South was the federal government, and it can be argued that the “Union” created by Lincoln and his Northern backers was actually a revolution against the American republic, supplanting it with a new system of equal rights, corporate money created by industrialization and the war economy, and an ever-expanding government controlled by plutocrats and big cities.

This was a radical, weird concept when I was growing up during the Civil War centennial, but it now has more than a few believers.

What about the slaves? Those in the movie are passive, kind, and uneasy. They want freedom but are not sure what to do with it. When Brown frees slaves and they sing a rousing spiritual, one asks: “What’s going to happen to us? Who’s gonna take care of us?” Brown replies they are now on their own, in God’s hands, and promptly leaves to finish off Stuart.

In a sense, this was how abolitionists thought of slaves. They were less real people than an ideal to be achieved, and in the last half-century, there has been a constant clash between what blacks represent and what they are.

At one point, a confrontation between Brown and Stuart sets a barn on fire. As Stuart fights his way out, he takes some blacks caught in the crossfire with him. A woman says: “If this is what freedom is like, I’d just as soon be a slave.” You may cringe. Such dialogue may have been inserted to please Southern audiences at the movies. But slaves had no say, historically speaking. Like today, they were waiting for the white man to do something. Note that in the BLM riots and statue desecrations, whites were on the front lines, especially white women — the spiritual descendants of Harriet Beecher Stowe?

As one film critic said a couple of years ago, blacks don’t want to be reminded of Uncle Tom’s Cabin; they want Spartacus. Perhaps that explains the success of Django Unchained, Tarantino’s antebellum fantasy where a black gunman goes on the warpath against evil whites to rescue his love. . . Broomhilda? A cartoon name for a cartoon movie, but such fantasies are what passes for enlightenment in contemporary culture. We seem on the verge of being ruled by a cross between commissars and cartoons. What a dark ride that’s going to be.

Nowadays, any sympathy for the Southern view is thoughtcrime. Santa Fe Trail would no doubt be at the top of the heap of a PC book burning. It’s a nascent White Nationalist film you should see, and it gets the history semi-right.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [5].

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.