Praise to Apollo, Dance of Dionysus: Death & the Dawn in Russian Ballet

Posted By Kathryn S. On In Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right | Comments Disabled6,629 words

This is an old and very cruel god . . .

We will endure;

We will try not to wince . . .

If indeed it is for your sakes,

If we perish or moan in torture,

Or stagger under sordid burdens

That you may live —

Then we can endure . . .

Without utter bitterness.

But, O thou old and very cruel god,

Take, if thou canst, this bitter cup from us. [1] [2]

Prologue: Origins

My mother worships three gods: the Anglo-Catholic God (she converted from the Methodist Church to Catholicism years ago), the god of fine textiles and fabrics — and the god of dance. She danced ballet for close to two decades, from the age of six or seven, until her twenties. Afterward, she kept her faded blush-rose slippers inside a wooden chest and at the foot of her bed. When I believed no one was watching, I would open the lock, and breathe in the cedar and teak, take them out and run my fingers along the satin and silk of their laces. I would marvel at the toe-pointes and try to imagine what their previous life — as part of the performances of The Nutcracker, Peter and the Wolf, Sleeping Beauty, and Firebird — was like. They seemed like magical shoes, belonging not to my mother, but to a sylphe who’d left them behind as a gift from the faeries.

I have no idea when humans began to dance — a few hundred thousand years ago? — nor do I know how it began in the first place. But I can guess. Dance is ritual (there are steps that one must follow, like a spell), and thus it seems likely to me that humans began to dance when they began to worship. Perhaps they saw their shadows jump and twist in the nighttime fire — or perhaps they were mimicking the fire itself as it swirled and licked and leaped, its smoke curling and blackening the air like a prayer made sentient. Here’s my bold hypothesis: when man began to light fires, man became a dancer (and it might explain one of the reasons why dance is so often linked with heat and passion). And because dance is fused with religion and worship, people have often danced for the dead, or have claimed that the dead themselves cavort restlessly, sometimes in the melancholy mistiness of the churchyard, and other times in devilish frenzy. In these early rituals, dancing in god-praise and reveling in earthly delights were joined. Death, dance, rite, and fire: discrete things that nevertheless have sometimes become one and the same.

Thus, dance has often been used as a kind of “rehearsal” for death and of madness. Hold hands, Ring-around-the-Roses, and In-Flew-Enza, darlings. Danse Macabre was a popular medieval/early modern genre in which the character “Death,” represented as a Grim Reaper or skeleton-figure, summoned people from all castes to join him in recognition of the fragility and vagaries of life. Giovanni Boccaccio’s collection of novellas, The Decameron (ca. 1353), in which seven young travelers came together to escape the Black Death outside the city of Florence was an example of this visual allegory made textual. Death is a beguiling partner, for who in the end can resist him?

New Orleans, that most deranged of American cities, where “the dead . . . [were] interred above the muddy gumbo of the soil to keep them from slipping away into the water,” regularly featured ad-hoc marches, concerts, and dance festivals in its overcrowded cemeteries. There, where the dead “[were] more numerous than the living . . . [ghosts] love[d] to congregate, haunt, and dance. Only the thinnest film, a razor-edge of twilight, separate[d] them from their descendents.” [2] [3] Yes, there is something “out of control” and dangerous about the dancer; drunks and madmen will whirl maniacally about; witches and temptresses will twist and spin. Many have appeared possessed by another, seemingly darker power, as if they were puppets on a string — a sensuous bacchanal to Dionysus and meant to inflame its voyeurs. Tonight we dance, for tomorrow we die! Only “the thinnest film, a razor-edge” too, separated the sacred from the profane (those who have used their bodies to express religious devotion have always tended to blur the two, or have made their separation altogether meaningless).

In stark contrast, ballet (called “civilization in a tutu” by some) is a very distant heir of these archaic dances around fires and burial grounds. [3] [5] On par with any of the beautiful achievements of our people, it too is worship — of the human form — and it too is a prayer to the gods of beauty and pain. The genre began in Renaissance Italy and then France as a form of court entertainment for the later Valois kings, and it thrived under the patronage of Catherine de Medici (1519-1589). A gradual shift from day to night time festivals during the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries (a show of power, since lighting up the early modern night could only be afforded by the wealthy) made court dance an evening spectacle. Louis XIV (1638-1715) performed in his first ballet at the age of fourteen and appeared at the finale as “le roi soleil,” a monarch dazzling his nighttime audience with the golden rays of the sun “and evoking his power to dispel the darkness.” Louis wasn’t simply acting the part of Apollo, but the ballet transformed him into Apollo, whose golden light shone on his subjects, great and small, noble and common — everyone under the sun. [4] [6]

Ballet, then, was in service to the prince and meant to enact “allegories of the state of the times” in the paired fundamental principles “regarding the display of power and authority. Like God, temporal rulers had to project their greatness in material creation. And common subjects had to be shown their sovereign’s majesty as directly as possible.” [5] [7] Michel de Pure’s Principles and Spectacles Ancient and Modern (1668), listed “ten forms of [pageantry]: theater, balls, fireworks, jousts, ‘Courses de Bagues,’ [6] [8] carousels, masquerades, military exercises, royal entries, and ballet,” each of which monarchs might use to impress both their people and their rivals. [7] [9] The German Protestant princes of Saxony and the dukes of Dresden, not to be outdone, developed in the 1660s a two-week-long festival whose centerpiece was “the Ballet of the Planets.” These tableaux, performed on fabulously illuminated nighttime stages, removed the earthy elements of death and plebeian worship, and placed dance in the realm of the immortal stars. Where might you have found these ballet dancers after they floated from the stage? East of the sun and west of the moon, perhaps. They were “celestial bodies,” used to promote the radiance (and distance) of kings and their courtiers.

But ballet gradually fell out of favor in Western Europe, where it was considered to be old-fashioned and stuffy (and revoltingly aristocratic by the time of the Revolution). It continued and thrived, however, in the east: in Imperial Russia, that glittering court of unequaled opulence and caesarian absolutism. Ever since Peter the Great (1672-1725), who spent his young adulthood traveling around Europe and absorbing its tastes and technologies, introduced it to the St. Petersburg art scene, ballet became an embraced Russian émigré. It is to the Russians (and their borrowings from some Italian methods) that we owe the technique and overall appearance of our classical and modern ballet.

And in its modern form, ballet is a meeting of art and sport in which they become one, like two colliding galaxies that dance and merge and separate, only to come together again, their spiral arms interlocked and waltzing across the cosmos. Its practitioners must make the most difficult physical maneuvers appear effortless. Viewers should be loath to look away. So, ballet is fairy-tale in form, myth en pointe. But it is also quite punishing. Ankle tendons wear thin, til they eventually snap, and knees bend in elegant, otherworldly form, until mortal limits rip them apart. Its dancers will have ugly, deformed feet forever. They might battle eating disorders for nearly as long. They sacrifice their bodies on the altar of beauty. Although it has the appearance of perfection, ballet has a cutthroat heart.

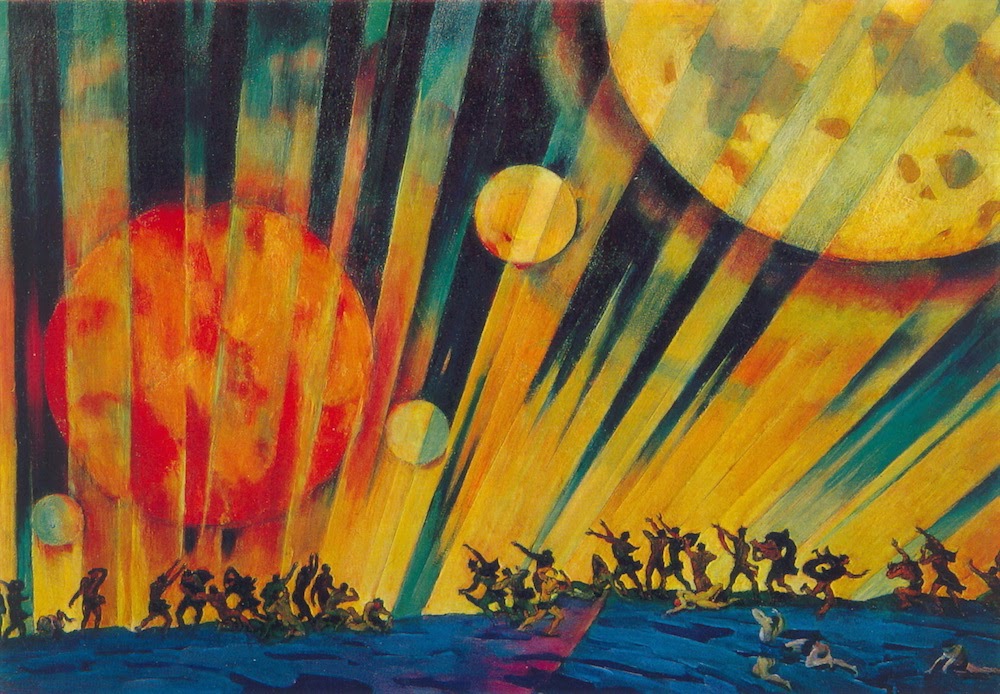

I contend that the Nieztschian dichotomy of Apollo and Dionysus has ruled the Western world’s myth-making and art-making for millennia, but that it was never so clear that such was the case than during the last years of fin de siécle Europe. [8] [11] Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), two of the greatest ballet composers of any era, were both Russian, both drawn to folk tales, and both fascinated by mysticism. Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty (1890) and Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) were musical scores that each dove into the shadowy world of magic, paganism, and maidenhood; death and vernal sacrifice — but did so in diametrically opposed ways. Sleeping Beauty was the finale of Victorianism, and Le Sacre ushered in a new and more pitiless age. In the end, it was a story of Western man’s condition, always seeking to touch the eternal, the skies in their heavens, but doomed to mortality and thus rooted to the earth and its cycles.

Act I: Danse Céleste

Dans ce moment la jeune fée sortit de derrière la tapisserie, et dit tout haut ces paroles: “Rassurez-vous, roi et reine, votre fille n’en mourra pas; il est vrai que je n’ai pas assez de puissance pour défaire entièrement ce que mon ancienne a fait. La princesse se percera la main d’un fuseau; mais au lieu d’en mourir, elle tombera seulement dans un profond sommeil qui durera cent ans, au bout desquels le fils d’un roi viendra la réveiller.” [9] [12]

In May of 1888, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, Russian writer and stage director, wrote to Tchaikovsky in a letter, proposing “The Sleeping Beauty” fable to his friend as the subject for a new ballet:

I am planning to write a libretto on ‘La belle au bois dormant’ . . . I would like a mise en scène in the style of Louis XIV, which would be a musical fantasia . . . If this idea appeals to you, then why not undertake to write the music? In the last act there would have to be quadrilles for all [Charles Perrault’s] fairy-tale characters — these should include Puss-in-Boots, Hop o’ My Thumb, Cinderella, Bluebeard, etc. [10] [13]

Mirroring the Russian adoption of French ballet, Tchaikovsky agreed to the proposal and adapted the French story of “La belle au bois dormant,” written by Charles Perrault in 1697, for the nineteenth-century Russian stage. “The subject,” the composer admitted, “[was] extremely likeable and poetic.” But he waited until Vsevolozhsky sent him a polished draft of the libretto before he committed to the project. After finally going over the lines as he was boarding a train from Moscow to Kyiv, Tchaikovsky wrote back, “I am hastening to inform you that the manuscript . . . has [at last] reached me . . . I have managed to read through the scenario and I very much wanted to tell you . . . that I am delighted and enchanted beyond all description. It suits me perfectly and I ask nothing more than to make the music for it. This delicious subject could not possibly have been better adapted for the stage . . .” [11] [14]

[15]

[15]Edmund Dulac, “The Sleeper,” an illustration in the 1912 book “The Bells” and Other Poems by Edgar Allan Poe

By this time, Tchaikovsky was nearing his fiftieth birthday as a celebrated opera composer who had already been involved in another Russian ballet (The Nutcracker) and many other musical scores. He was a favorite of Tsar Alexander III, and he returned that favor ten-fold; an Imperial enthusiast was he. Throwing himself into his work, Tchaikovsky finished the ballet in the space of several months. By the time of its first 1890 performance on the stage of the Mariinsky Theater of St. Petersburg, The Sleeping Beauty bore only a superficial resemblance to its French primary source. It had disposed of the Dionysian elements (rampant death, drunkenness, sex, and cannibal mothers-in-law) and highlighted the Apollonian themes befitting the Victorian sensibility. The prima ballerina’s role was even named “Aurora,” or “the Dawn” (amusingly, the Prince was called “Desiré,” a name that has since been appropriated by black women living in America). In the story, Aurora was visited on her christening day by an evil fairy, who prophesied that the infant would prick her finger on a spindle and thus fall into a long coma, broken only by a Prince Charming from the future. With her eventual awakening, so too rose the dormant old kingdom of her youth.

Tchaikovsky was notorious for developing a hatred for his work after the initial flush of congratulations and completion (he grew to detest his most popular ballet, The Nutcracker), but his opinion of The Sleeping Beauty never wavered. He later confessed to a friend that it “may [have been] the best of all my compositions, and yet I wrote it improbably quickly,” a cheerful piece of news for those who prefer to procrastinate and do their best work while crunched for time. [12] [16]

Dionysus and Apollo in the Russian Romantic Era

Like many Russians who ran in aristocratic circles during the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky was torn between attachment to his Russian heritage and his love of Western culture and refinement. For its part, the West exalted him beyond many of its own musicians. While the composer was touring the US In 1891, The New York Herald declared its “selection of living geniuses,” and topping the list was “Bismarck . . . of course,” followed by “Edison, Tolstoy, Sarah Bernhardt, Ibsen, Herbert Spencer, Dvorak and Tchaikovsky.” [13] [17] There were a pair of Russians in the Herald’s batch of overachievers: himself and the great Russian writer of War and Peace and Anna Karenina (1828-1910).

The two men would seem at first to have been unalike. Leo Tolstoy was a robust and red-blooded heir of a country estate, who loved to mingle with the common people. He went about his days in the dress of a working man’s shirt and spent his nights in the beds of peasant women, whom he found irresistible. Tchaikovsky, meanwhile, was an urbane (and probably homosexual) man, whose artistic work was targeted toward the upper and middle classes. He was a staunch supporter of the Romanovs, to whom he owed much of his celebrity and titles. But the composer loved War and Peace, and like Tolstoy, shared a passion for Russian folk songs. The two artists only met once, and at this tête-a-tête Tchaikovsky arranged for the Andante Cantabile “from the D major string quartet, based on a Ukrainian folksong,” to be played in his idol’s honor. [14] [18]

There were rumors, meanwhile, that Tolstoy wrote the first forty pages of War and Peace (1869) in French. Then, perhaps remembering who the enemy was, he switched to Russian. True or not, the apocryphal story revealed the very real conflicts waged in nineteenth-century Russia amongst the aristocracy. For his part, Tolstoy romanticized the Russian peasant as “authentic” and lambasted the effects of Westernization and the Industrial Revolution on the cities and upper classes. The author used satire “to make the serious point that the Westernized Russian elite had become foreigners in their own land, disconnected from their own language and culture. How to reconnect with a real or imagined ‘Russianness’ was the predominant theme of Russian literature, painting and music throughout the nineteenth century.” [15] [19]

And this conflict appeared not only in language, but in dance. In a famous scene of War and Peace, Natasha, a young noblewoman (and Tolstoy’s feminine ideal), ventured out of the drawing-room and into a rustic country cabin, filled with simple folk. Her “Uncle” struck a tune. And then, Natasha began to dance. Amazed, all who watched wondered:

Where, how, and when had this young countess, educated by an émigrée French governess, imbibed from the Russian air she breathed that spirit and obtained that manner which the pas de châle would, one would have supposed, long ago have effaced? But the spirit and the movements were those inimitable and unteachable Russian ones . . . Anísya Fëdorovna [her uncle’s unofficial “peasant wife”] who had at once handed her the handkerchief she needed for the dance, had tears in her eyes, though she laughed as she watched this slim, graceful countess, reared in silks and velvets and so different from herself, who yet was able to understand all that was in Anísya and in Anísya’s father and mother and aunt, and in every Russian man and woman. [16] [20]

As a writer, Tolstoy had a “yearning for a broad community with the Russian peasantry which [he] shared with the ‘men of 1812,’ the liberal noblemen and [nationalist] patriots who dominate[d] the public scenes of War and Peace.” Of music, he was even more explicit: “I became convinced . . . that a piece of music such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony [was] less worthy of admiration than Vanka’s song or the lament of the Volga boatmen.” [17] [21] The book’s publication coincided with the emancipation of the Russian serfs in 1861. There was afterward an ambiguity on the part of the intelligentsia and nobility concerning this new class of free Russian people. How to relate to them; to incorporate them into both Russia as a nation and Russia as a Tsarist empire? Could the Apollonian Tchaikovsky of the upper class merge with the Dionysian Tolstoy, the moody curmudgeon who championed the laborer? Would this be the “dawn” of a new age? It would take the ending of the Victorian era and the beginning of the twentieth century before another Russian artist gave an explosive answer.

Interlude: Modern Barbarians

We do not admire the man of timid peace. We admire the man who embodies victorious effort; the man who . . . has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life. [18] [22]

The “explosive answer,” of course, was Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring). But before delving into that seminal ballet, that violent mirror of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty, it’s necessary to explore the context of Europe during the last decades of its golden age. What in European society, waning to an Edwardian autumn, had changed over twenty-three years (from the first 1890 performance of Sleeping Beauty to the 1913 debut of Le Sacre) that made such a piece — an un-ballet Ballet teeming with the violence and the riot of springtime — possible?

One of the more pervasive patterns in Western history and culture has been the periodic rhapsodizing Europeans have dedicated to “the primitive.” Romans of Antiquity were both repulsed and impressed by the barbarian Germanic tribes — those blond giants of the north who refused to bend the knee to Caesar and his legions. Jean Jacques Rousseau infamously waxed sentimental about the “noble savage” in his eighteenth-century lament of lawful society. Almost as soon as New Englanders ran off the last of the Indians from their hills, they sentimentalized them in melodramas, like Metamora (1828). As explained, Russian writers during the Victorian era, like Tolstoy, idealized serf and peasant life in the steppes. In H. G. Wells’ futuristic Time Machine (1895), the principles of Darwinism had reversed, and the class conflict of Victorian England had caused both the upper and the lower classes to de-volve, the former into disease-free, communal androgynes, and the latter into hideous cannibals. There was a moral panic in the late nineteenth century surrounding the effeminate decay of Europeans, during which everyone from Sigmund Freud to Teddy Roosevelt bemoaned the “over-civilized” Western man. Unless he embraced “the strenuous life,” he risked turning into Eloi sheep — pretty but stupid prey for colored Morlocks to hunt after dusk. (White people today idolize primitives so much that they welcome Third World gang members and rapists into their countries, while they celebrate the savagery of blacks with yard signs). [19] [23]

In an ironic reversal of centuries prior, Parisians of the Belle Epoch couldn’t get enough of Russian “Asiatic barbarism.” The 1900 Paris Exhibition included “a fantasy Kremlin,” Trans-Siberian Railroad, and a recreated Russian village along the Seine. Actual Russian peasants with overgrown beards were imported for the occasion. “Harem pants” and turbans were all the rage. [20] [24] The Russian ballet companies, whose people had appropriated the original French dance, reintroduced it to a Parisian society hungry for “the Orient,” and made it new again with exotic and pagan elements.

Added to this fin de siécle fascination and imperative for “the primitive” was the advent of “simultaneity,” or the modern understanding of time, space, direction, and speed. The perception of each of these things changed during the late nineteenth century. Telegraphs, telephones, aeroplanes, motorcars, and bicycles achieved a previously unheard of kind of machine and motion. A play based on Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days was spectacularly successful and made its 1,550th appearance in the French Châtelet in 1898. [21] [25] By the eve of the First World War, time had become both relative and homogeneous — the fourth dimension of space that allowed authors like Wells to imagine technology capable of navigating through the interstices of matter — but also the “standardized” time necessary to carry out mass mobilizations and complex military maneuvers. In 1890, wristwatches were considered unmanly, but at the Battle of the Somme, they had become an essential component of a military equipment kit. On July 1, 1916, and at the stroke of half-past seven, each soldier’s wristwatch was synchronized so that all down the line, every platoon leader blew his whistle at once, and sent entire armies up and over the parapets and into the killing fields. [22] [26] Rolex owes its success to the massacres of Flanders and the failure of the Schlieffen Plan. War was a “savage dance,” whose steps forward and retreats backward were now as precisely choreographed as any Russian ballet.

[27]

[27]Modern technology in the service of barbarism: Australian soldiers wearing to war the new male accessory, ca. 1916

It is important to note that the world of one-hundred years ago was “modern,” but it was not ours. When reading primary sources, readers will be struck with the alienness, as well as the familiarities of the near-past. Women complained about the forever-lack of fresh linens. Men still fought duels. Both had to navigate cobblestones that destroyed shoes and carriage wheels while picking their way among the ubiquitous piles of horse manure left on the streets. They worried about the dangers of food that spoiled naturally and rapidly. [23] [28] And this new “simultaneity,” the sense that time, space, and distance were somehow collapsed was, for many, jarring. It resulted in an artistic movement (known as Modernism) that reflected these altered perspectives on reality. Suddenly, paintings began to resemble “explosions at a shingle factory,” and writers began to disregard the old rules that dictated the necessary requirements of “poem,” “novel,” and “composition.” Above all, Modernism was rebellion against Victorian values. The Age of Apollo, the idea of Truth and certainty, the worship of beauty and order, was beginning to wither; the mania and chaos, the primitivism of Dionysus was taking root. Shocking bougie sensitivities was not only desired, but essential. In short, the lure of heresy and the heathen in an age of iconoclastic change was overwhelming. [24] [29] Modernism was a marriage of the New Man and the barbarian energy that propelled forward both him and his new machines.

Act II: Danse Macabre

Stirb und werde — Die and become

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Igor Stravinsky was a flagrant embellisher. He often told tall tales about life in old Russia, his childhood, and one in particular, when, at the age of ten, he attended a concerto. As he was leaving the theater, he emerged into the aisle and stood just across from a fifty-two-year-old Tchaikovsky, who had his back turned. For a brief moment, the two great “planets” of Russian ballet aligned. Tchaikovsky died one year later. [25] [31] It was another two decades before Stravinsky created a work that would go down as one of the paramount events in modern art history. The idea for the piece came to him, he claimed, in a sudden dream: “I saw in imagination a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring.” Indeed, the finished score was a fantasia of two acts, the first a coming-together of the men and elders to praise the earth, and the second followed a group of young women as they chose a maiden, glorified her, and offered her up as a blood sacrifice to “Yarilo the magnificent, the flaming.” [26] [32] The Ancestors, meanwhile, bore witness.

At the core of Rite is the deep spiritual knowing that violence can be creative, regenerative. Stravinsky wanted not just to evoke an ancient sacrificial rite of pagan Russia, to tell its story, but to relive (short of murder) “that ritual on the stage and thus communicate in the most immediate way the ecstasy and terror of the human sacrifice.” [27] [33] We’ve known — we’ve always known — that the only currency worth anything to the gods and Fate is blood. The magic juice that stains and purifies; infuses life, but ebbs it, too, away. “How can we take you seriously, mortal, unless you shed that which is most precious to you and your kind?” ask of us the gods. “My pleasure is your pain. Then, we may bargain, after this ransom, paid.”

Although he later downplayed the “folklore” aspect of Le Sacre, [28] [34] Stravinsky borrowed heavily from the rustic music of the countryside. But just as he drew from pagan Russia and peasant folk culture, Stravinsky wanted also for the music itself to clash with the sound and fury of the modern world, to resonate with “all its dislocations and noises and terrors,” to convert “’the rhythm of the steppes into the scream of the motor horn, the rattle of machinery, the grind of the wheels, the beating of iron and steel, the roar of the underground railway and the other barbaric cries of modern life; and to transform these despairing noises into music.'” [29] [35] And so, Le Sacre was a marriage of what may at first have seemed like opposites, but were instead, the extracts of civilization. Ballet, that technically exact celebration of celestial grace was distilled to the primeval essence of dance itself: ritual and blood-craze, whose destructive eroticism was both repulsive and seductive. Twentieth-century life, all its industry and its technology and its crowns of skyscrapers clambering toward the heavens, collapsed into the unequaled barbarism of a new age. This was the genius of Le Sacre, and this was why it was ugly.

Recall that Aurora of Sleeping Beauty was a forever-spring maiden who had not aged for a century, when she was finally awoken from a dead sleep, foiling at last the designs of a wicked fairy. Like the “dawn,” of her namesake, she brought the rest of her kingdom to life once again when she rose from her slumber. By contrast, no “villain” cursed the sacrificial virgin of Le Sacre with death, but a group of her peers singled her out in a primitive ritual. Instead of rising like the sun in its heavens, the victim was absorbed into the earth. Sleeping Beauty worshipped the Delphic sun god, Apollo, while Le Sacre’s dancers spilled the blood of their own to appease the heathen sun god, Yarilo. The one was the stuff of sugar-coated fairy tales, or the Danse Céleste; while the other beat out the percussives of a nightmare, or the Danse Macabre. And, of course, the music of each could not have been more different from one another. In a way, Le Sacre was less avant-garde and more ancien, marrying Dionysus and Apollo into one cruel, beautiful god as he appeared to the fire-worshipers of the early Indo-Europeans.

“Le Massacre” du Printemps

On 29 of May 1913, wealthy snobs and artistic snobs of the intelligentsia mold swept into the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées to watch the Ballets Russes Company perform the debut of Le Sacre du Printemps. [30] [36] Stravinsky, too, was in attendance. Even though the Théâtre could only seat one to two hundred audience members at a time, nearly everyone who could plausibly have been in the vicinity of Paris that night claimed they were at the ballet’s opening (including Claude Debussy, Mata Hari, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, and Jean Cocteau). The wild stories and speculation about that night must, then, be viewed with skepticism. But whatever happened, it was shocking enough to have caused a breakdown in law and order and to have turned respectable ladies and gentlemen into rabble-rousers.

As everyone took their seats and the lights dimmed, a weird bassoon sound commenced to wail from the pit. In the boxes, women raised their binoculars. The sound continued, and faint grumblings began. Eventually, the curtain rose on a set of dancers decked out in dirtied costumes meant to resemble the peasant garb of ancient Russia. There were no elegant pas-de-deux or lightsome twirlings. Instead, they began an ugly, primitive, knock-kneed stomping ritual onstage, movements that emphasized their weight and awkwardness, rather than the gravity-defying grace of classical ballet. The horrible pounding coming from the orchestra continued. At this point, the audience rebelled. Howls, hissing, and jeering erupted. According to Romola Najinsky, society ladies “spat” in men’s faces. [31] [37] The elderly Comtesse de Pourtalès, “getting up, coronet askew and waving her fan exclaimed: ‘This is the first time in sixty years that anyone has dared make fun of me!’” [32] [38] Punches were thrown. Cards were exchanged to exact satisfaction and a date with the dueling pistol. Indeed, “there was such a din that the music . . . [was] drowned out completely.” One dance critic remembered that “‘cat-calls succeeded playing the first few bars . . . and then ensued a battery of screams, countered by a foil of applause. We warred over art . . . some forty of the protestants were forced out . . . but that did not quell the disturbance. The lights were’” flashed off and on, and the audience became “as much a part of this famous performance as the corps de ballet.” [33] [39]

Two days later, a disgusted editor for Comœdia asked: “So where on earth were these bastards brought up?” It was clear from the article that he referred both to Le Sacre’s “vile and stupid” haters and the precious aesthetes who were the ballet’s supporters. Perhaps the reporter even took aim at the Ballets Russes producers themselves, whose œuvre was asking for a scandal. “It was only by cupping our ears in the middle of an indescribable racket,” he continued, “that we could painfully grasp an approximate idea of this new work, which was drowned out equally by its defenders and its adversaries . . . this was not Le Sacre, but Le Massacre Printemps.” [34] [40] Given the current times, it’s somewhat endearing that one-hundred years ago people were rioting over a ballet while in their evening dress and jewelry.

One press release, meanwhile, offered a more sanguine opinion and lauded “the wonderful Russian dancers [who] could portray these first stammered gestures of half-savage humanity; only they could represent these frenzied mobs of people who stamp out untiringly the most startling polyrhythms ever produced by the brain of a musician,” an assessment that seemed, nevertheless, a backhanded compliment. [35] [41] To Parisians, Russia was a producer of mad geniuses, fire-water, and brutes.

Finale: Which Ballet, Western Man?

Beauty is a great paradox —

Music’s secret soul creeping about the senses

To wrestle with man’s coarser nature.

It is hard when beauty loses. [36] [43]

It is perhaps even harder, given Le Sacre’s immediate aftermath and the outbreak of European conflict, not to view it as prophecy. The brave new world of the twentieth century was born atop a charnel house of the Great War’s sacrificial victims. [37] [44] Indeed, next to the trenches, the ballet’s bloody-minded pagans looked civilized. One soldier, writing in his 1917 diary, commented that “Often during the scientific, chemical ‘cubist’ warfare, on the nights made terrible by air raids, I have thought of the Sacre.” [38] [45] It was clear from context that the author alluded to Stravinsky’s dissonant ballet, but he could also have been thinking of “the Sacre” of Christ and the fate of Christian Europe, whose civilization had descended into flame and atrocity. Neither Europe nor the art world has recovered from the implications of Igor Stravinsky.

Should art be true; should art be beautiful? Should art be novel? “Art,” said Stravinsky, “should be true to life, but art will therefore not be beautiful.” The phrase “ugly truths” exist for a reason, after all; ask anyone who has been tempted to live a lie. But doesn’t “artful” mean deceptive? Isn’t art, by its very nature, not true, but only ever an imperfect rendering of something else, an artifice? And because art is never true (and we’ve already disposed of beauty), the whole exercise is rather pointless. Well, readers, this line of thought has proven . . . ultimately unfruitful. It has given us wonderful lines like: “a Rose is a rose is a rose,” and “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” [39] [46] We have Campbell Soup cans in neon pink and green; and urinal fountains of porcelain curves and scribbled sides.

The absurdity of art pieces like these might have been (paradoxically) meaningful during the senseless slaughter of World War I, but Western culture has not moved on from the brutalism of Stravinsky and Dada (and I like Stravinsky’s music, and there are quite a few Modernist artists whose work I do admire). But when will the twentieth century end? Out, damned spot! There was, indeed, too much blood in it. [40] [47] “Great” art is now neither true, nor serious, nor beautiful; it is therefore not any good. What will future generations admire when touring “the Dark Age” section of the exhibit? Your guess is as good as mine, readers. Perhaps my kooky art classmate will have won a spot for her “found objects” wrapped in fortune-cookie slips. It may seem strange, that in a handful of decades, we lurched from staged blood sacrifice to hammers plastered with Chinese kitchen kitsch (worse, Africans now dance to Sleeping Beauty), but such is the fate of even the proudest people when they subject the very things for which they should feel pride instead to unending derision; and so the proudest people become vain (and thus incapable of glory).

Most of all, they miss an important aspect of Stravinsky’s ballet: the rebirth, “the spring,” that follows brutalism, that results from sacrifice, that succeeds the virgin collapsing on a burgeoning bed of dahlias. Oh, yes, they’ve made Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” the theme song of the Council of Europe and the anthem of the European Union. I suppose this is to signal the continent’s “rebirth” from the suicidal World Wars and the bleak existence of the postwar years. Despite this window-dressing, I’m afraid we’re still dancing the death-spiral, readers, and we must awaken ourselves and shake the rest of the West from this overlong danse macabre that has not concluded since that hot Parisian night in spring.

But wisdom shows up in unexpected places. In one of the books I used as a reference, there was a note written on the title page and in strikingly elegant cursive: “To Cynthia, 1978: Ballet never becomes easy, it becomes possible.” If mortals can train themselves to dance and defy gravity, then perhaps we can defy those forces that hold us back as well. Saving the white race will never become easy, readers, but if we persist in our truths, it will become possible.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [48] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [49].

Don’t forget to sign up [50] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [51] Richard Aldington, “Vicarious Atonement [52]” (1916)

[2] [53] Andrei Codrescu, New Orleans, Mon Amour: Twenty Years of Writings from the City (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books, 2006), 176.

[3] [54] Laura Jacobs, Celestial Bodies: How to Look at Ballet (New York: Basic Books, 2018), 5.

[4] [55] Craig Koslofsky, Evening’s Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 93.

[5] [56] Ibid., 95.

[6] [57] “Courses de Bagues” were equestrian ring tilts, similar to jousts, in which contestants would attempt to charge and decapitate a straw-man, usually while riding around circularly.

[7] [58] Evening’s Empire, 96.

[8] [59] Friedrich Nietzsche fleshed out his Apollonian/Dionysian dichotomy in The Birth of Tragedy (1872), although it had been discussed by certain German philosophers before him. Some of Nietzsche’s arguments were contradictory, but his overall analysis posited that “the Apollonian” (which included movements like the Enlightenment) were manifestations of logic, rationality, and virtue. “The Dionysian,” (which included Romanticism), stressed emotion, art, irrationality, nature, and sensual pleasures.

[9] [60] Charles Perrault, “La belle au bois dormant. [61]” My translation reads:

In that moment, the young fairy emerged from behind the tapestry, and declared these words: “Console yourselves, king and queen, for your daughter will not die; it is true that I cannot undo entirely what my elder kinswoman has decreed. The princess will prick her finger on a spindle; but instead of dying, she shall only fall into a deep sleep for one-hundred years, after which a son of a king will awaken her.”

[10] [62] Letter from Ivan Vsevolozhsky to Tchaikovsky, 13 May 1888, Klin House-Museum Archive.

[11] [63] Letter 3643 from Tchaikovsky to Ivan Vsevolozhsky, 25 August 1888, Klin House-Museum Archive.

[12] [64] Letter 3909 from Tchaikovsky to Nadezhda von Meck, 6 August 1889, Klin House-Museum Archive.

[13] [65] Edward Garden, “Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky,” in Music & Letters 55, no. 3 (1974), pp. 307-316, 309.

[14] [66] Ibid., 312.

[15] [67] Orlando Figes, Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Picador, 2002), 6.

[16] [68] Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace [69], trans. Louise and Aylmer Maude, Project Gutenberg, Book 7, Chapter 7.

[17] [70] Natasha’s Dance, 8.

[18] [71] From Theodore Roosevelt’s speech at the Chicago Hamilton Club, “The Strenuous Life [72]”; Roosevelt’s idea that Western man needed to “shape up” was laudable, but the majority of the speech focused on taking up the “White Man’s Burden” abroad, something that proved to be a mistake.

[19] [73] On the other hand, I could argue that the Dissident Right’s interest in resurrecting the “old gods” and bygone pagan belief systems are also a form of this idealization of “the barbarian,” of the need to reinvigorate the West with something elemental to it.

[20] [74] Gillian Moore, The Rite of Spring: The Music of Modernity (London: Head of Zeus Books, 2019), 36.

[21] [75] Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003), 164.

[22] [76] Ibid., 288.

[23] [77] Ibid., 6.

[24] [78] See Peter Gay, Modernism: The Lure of Heresy, from Baudelaire to Beckett and Beyond (New York: Norton & Norton, 2010).

[25] [79] The Rite of Spring: The Music of Modernity, 17.

[26] [80] Ibid., 49, 52.

[27] [81] Ibid., 7.

[28] [82] This reticence to discuss his folksy “Russian Phase” was owed to his later disdain of so-called “proto-Soviet” intellectualism that placed the common Russian people on a pedestal. There were few things Stravinsky loathed more than the Soviet regime.

[29] [83] Such was T. S. Eliot’s assessment in a “London Letter” published in the Dial (October 1921).

[30] [84] The Ballets Russes and its founder Sergei Diaghilev were the most influential players in fin-de-ciécle ballet.

[31] [85] Modris Eksteins, Rites of Spring (New York: Mariner, 2000), 12.

[32] [86] The Rite of Spring: The Music of Modernity, 72.

[33] [87] Rites of Spring, 12.

[34] [88] The Rite of Spring: The Music of Modernity, 67.

[35] [89] This is a quote from a Théâtre des Champs-Élysées press release, published in Le Figaro (May 29, 1913).

[36] [90] Isaac Rosenberg, excerpt from The Amulet in Penguin Book of First World War Poetry, 226.

[37] [91] This thesis is examined in Modris Eksteins’ Rites of Spring (1989).

[38] [92] This is a quote from the French portrait-painter Jacques Émile-Blanche in Portraits of a Lifetime, ed. Walter Clement (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1937), 260.

[39] [93] These are references to Gertrude Stein’s famous deconstruction of language and surrealist artist René Magritte’s painting of a pipe with the caption: Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

[40] [94] This, too, is a reference — a literary one to a scene from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606) during which Lady Macbeth suffered an attack of conscience and subsequent descent into madness. A disappointing end for such a formidable character, honestly.