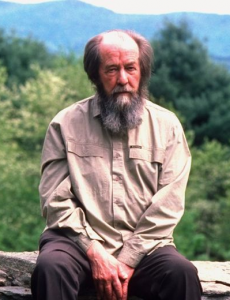

Jews, Fake News, & Interviews: The Memoirs of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,083 words

The memoirs of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn are unique in his vast body of work given that they serve more as metadata than data regarding the man’s impact upon the culture and perspective of the political Right. I’m sure this could be the case with the memoirs of any important person. However, with Solzhenitsyn, so often his work was his life. He drew directly from his experiences as a zek to develop his early works, such as his prison plays [2], his unproduced screenplay The Tanks Know the Truth (about a gulag uprising), One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, and, of course, the sprawling Gulag Archipelago. He really did serve time in a prison research institute as depicted in In the First Circle. He had been a schoolteacher in the sticks after his release from the gulag as was the narrator in his short story Matryona’s House [3]. He also, quite famously, had been a recovering cancer patient in a hospital, just like Kostoglotov in Cancer Ward.

So, it would make sense for any student the Right to study Solzhenitsyn’s memoirs to gain greater perspective on the mind of this great man. Solzhenitsyn’s primary intent seems to be to tell the story of himself as a writer and famous figure. He tends to gloss over personal and family drama and instead focuses most on his strife with the Soviet authorities, his ideological enemies, and unscrupulous writers, publishers, and other literary frauds, as well as his peregrinations, his never-ending research, and his own perhaps official views on important matters.

The memoirs that have been translated into English so far, in order of publication, are The Oak and the Calf, Invisible Allies, and Books One and Two of Between Two Millstones. These cover his life as an author from the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw” of the early 1960s — when One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published in the Soviet literary magazine Novy Mir (New World) — to the early 1990s when Solzhenitsyn and his family, caught between giddiness and dread, were about to return to a newly-re-formed Russia after a twenty-year exile in the West. Many of the themes are non-political yet interesting in their own right. The lengths he went to survive as a dissident author under the repressive Soviets should inspire any dissident writing anywhere. Solzhenitsyn’s story, if anything, is one of perseverance.

On his brush with death in the cancer ward, he writes in The Oak and the Calf:

I did not die, however. (With a hopelessly neglected and acutely malignant tumor, this was a divine miracle; I could see no other explanation. Since then, all the life that has been given back to me has not been mine in the full sense: it is built around a purpose.)

So nothing short of assassination would have stopped him (the KGB, as a matter of fact, attempted just that on at least two occasions). With such a mindset, hiding pages in book bindings and manuscripts in boxes with false bottoms, constantly burning typewriter ribbon, training yourself to have tiny handwriting, photographing pages for microfilm, keeping track of who has what version of which manuscript and where, knowing which ceilings you could speak under and which telephones you could use, knowing whom to trust to smuggle the material to the West, and other such subterfuges were the ruthless and logical means to the end which Solzhenitsyn had ascribed to himself after his cancer scare: to write for Russia. And for the zeks. Never for a moment do his fellow zeks leave his heart or his mind. In Between Two Millstones Part One, he writes, “I do not consider the income from Archipelago mine; it belongs to Russia, and above all, to the political prisoners, our brothers.”

Invisible Allies gives us as good a summation of Solzhenitsyn’s zekness as any:

[Georg] Tenno’s wife, Natasha, a Petersburg native of Finnish extraction, at one time a flaxen-haired, fragile young woman, was now also a seasoned zek, having “pulled a tenner” like her husband. She had the same philosophy of life as the rest of us — namely, that the really immutable things are the camps, the prisons, the struggle, and the Communist hangmen, while life “outside” is just an odd and temporary anomaly.

These memoirs also contain precious anecdotes that indicate how a man who can think so probingly both forward and backward in time just can’t seem to fit in the present. Nor does he want to. While still in the Soviet Union, he had the opportunity to meet Jean-Paul Sartre and refused, dismissively referring to the aging French existentialist as a “wandering minstrel of humanism.” His memoirs often become poignant as well, with few scenes topping the fate of Elizaveta Voronyanskaya, an irrepressible and doggedly loyal typist and researcher who aided Solzhenitsyn with The Gulag Archipelago in the mid-1960s.

Great nuggets of knowledge pop out as well. Did you know that the Soviet Union reserved camps in the Arctic Circle for war cripples? Solzhenitsyn didn’t either, until his editor at Novy Mir let him in on the secret. In a Potemkin Village writ large, these poor souls had been “cast out so that they would not mar the carefully arranged tableau of Soviet life with their stumps of limbs. . .”

Did you also know that Solzhenitsyn exchanged chummy letters with ultraconservative North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms [4]? Helms was one of the first Americans who contacted him once he arrived in Zurich after his expulsion from the Soviet Union. They had met in Washington, DC years later. In fact, only days into Solzhenitsyn’s exile, Helms introduced a bill in the Senate to name Solzhenitsyn an “Honorary Citizen of the United States,” an honor which had been bestowed previously only to two individuals: Lafayette and Winston Churchill. The Senate passed the bill, but it died in the House which was loath to upset the Soviets over their banished man of letters.

Aside from being interesting on its own merits, Solzhenitsyn’s memoirs have special value for the modern Dissident Right for two primary reasons. First, Solzhenitsyn constantly expresses himself in ethnonationalist terms. As with most of his non-fiction, a reader can substitute “Russian” with “white” in many places, and suddenly this Cold War ex-Soviet zek becomes immediately crucial to the goings-on within the “White-Positive Sphere” of modern dissidents. Solzhenitsyn also never hesitates to skewer the enemies of ethnonationalism (namely, the Left — both in the East and West) for its hypocrisies, shabby ideas, and slovenly morals. One could fill a notebook with the sarcastic jabs and sardonic aphorisms found in his memoirs. For example, when referring to the Western liberal elites in Millstones Book Two, he writes:

No, deny it all you like, but our humanitarian intelligentsia has the same roots, the very same roots as the Bolsheviks.

With all the draconian censorship, deplatforming, and oppression of conservatives in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidential victory in 2016 as well as with the tacit acceptance Western elites have shown towards terrorist groups such as Black Lives Matter and Antifa, how is this statement not as prophetic as it is cutting?

Solzhenitsyn’s ethnocentrism speaks for itself in his memoirs, and the best a reviewer can do is reproduce a few of the best passages so the author’s modes of expression can resonate with today’s dissidents. Here are four:

Besides, [Igor] Shafarevich was from birth inseparably tied to Russia, the land and its history: they are one flesh, with a common bloodstream, a single heartbeat. His love of Russia is a jealous love — to make up for the past carelessness of our generation?

— The Oak and the Calf, Fourth Supplement

I never ceased to lament that this great son of our people [Andrei Sakharov], having always paid such a high price to assuage his conscience, would not take to heart the great task of our people’s national rebirth.

— Between Two Millstones, Part One, Chapter Three

The blood of Russian history was draining into the sand.

— Between Two Millstones, Part Two, Chapter Six

But both to the new democrats from the USSR and the entire radical warrior-host of the American press I’m not the one who is so very important — it is, rather, Russian memory, the reviving Russian consciousness that I personify.

— Between Two Millstones, Part Two, Chapter Six[/ind]

If only a majority of whites today had this kind of attachment to Europe or to themselves.

We should also keep in mind that Solzhenitsyn also faced quite a bit of heat from the Russian Far Right. This is perhaps why in his 1982 letter to Ronald Reagan he claimed that he was not a nationalist but a patriot. Those known as “Russian nationalists” in the 1980s did not, according to Solzhenitsyn, believe in Russia for Russians, Armenia for Armenians, Kazakhstan for Kazakhs, and so on. Instead, they longed for “‘Great Russia’ in her imperial incarnation” — a truly anti-nationalist position that Solzhenitsyn rightfully refused to defend.

[5]

[5]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s novel Charity’s Blade here. [6]

The only possible exception here would be his hesitant attitude towards Ukrainian nationalism. Solzhenitsyn, who was part Ukrainian himself, viewed the Ukrainians as essentially brothers with Russians. He was reluctant for Ukraine to part with Russia because he loved Ukrainians, not because he wished to rule over them. In Millstones Book One, he writes, “I have always felt it my duty to bring Ukrainians and Russians together in friendship.” He also states that in the event of a Russian-Ukrainian war, he would stay out of it completely and forbid his sons to take part in it as well.

Second, Solzhenitsyn candidly lays out his side of the story regarding his well-known friction with the Jews, especially in Millstones Book Two. But this memoir, the latest to be translated into English, was written nearly a decade before he penned his famous treatise on the Jewish Question Two Hundred Years Together. So the Jewish Question is never addressed front and center in his memoirs. However, it does raise its snout in a variety of ways — notably in his relationships with individual Jews who let him down or betrayed him for a variety of reasons, and in his own, usually off-the-cuff, critical assessments of Jews.

Of this first category, the most prominent appears to be Lev Kopelev, the prototype for the character Rubin in In the First Circle. Kopelev appears as the author’s “prison friend” as early as page sixteen of The Oak and the Calf, on which he assists placing the manuscript of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich with the Novy Mir editors in 1961. Throughout the volume, he remains the author’s steadfast benefactor. However, Invisible Allies tells a different story. In 1965, Kopelev had behaved irresponsibly with Solzhenitsyn’s still-secret poem Prussian Nights. Before he was supposed to deliver it to German author Heinrich Böll to smuggle it to the West, he had lent it to his sister-in-law who, in turn, lent it to a friend who had made a copy. This copy eventually fell into the hands of the KGB, which placed Solzhenitsyn’s life in grave danger. After Solzhenitsyn’s deportation, Kopelev later reviled the ethnocentrism and Orthodoxy found in Solzhenitsyn’s essay collection From Under the Rubble [7] and often abused his former friend in writing thereafter.

To be sure, Solzhenitsyn had gentile enemies, most notably fellow dissident author Andrei Sinyavsky and translator and publisher Olga Carlisle. But of his friends and allies during his Soviet dissident days, the gentiles tended to remain that way (or at least not become his outright enemy, as in the case of Andrei Sakharov), whereas the Jews less so. Another example is philologist Efim Etkind who had enabled Solzhenitsyn to secretly and illegally view the inside of a historical building in 1972 as part of his research for The Red Wheel. Before the decade was over, however, Etkind had become one of Solzhenitsyn’s most vociferous critics, at one point smearing him as a “Russian Ayatollah.”

The second way in which Solzhenitsyn addresses the Jewish Question often includes unmotivated comments which criticize or embarrass Jews as a group — typically not enough to warrant a charge of anti-Semitism, but certainly displaying a refreshing lack of sensitivity towards the Jewish people. For example, in The Oak and the Calf, he describes how “a group of some ninety Jews had addressed a written appeal to the U.S. Congress — as usual, on behalf of the Jews.” He didn’t need to include the “as usual,” but did so as a way to demonstrate the typical Jewish double standard: ethnocentrism for me and not for thee. His various swipes at Jewry include some humorous moments as well. Most striking is his letter to the editors of Nasha Strana (a Russian language Israeli newspaper) and the Jerusalem Post, which he includes in the appendix of Millstones Book One. Although written in all seriousness, it hits the Jewish Question in an embarrassing place. Here it is in its entirety:

In order that The Gulag Archipelago might be read by the widest possible audience and be easily be acquired by anyone, I have instructed all my publishers that the retail price of this book must be set at two, three, or even four times less than is customary for books of this size. Meanwhile, I am donating all my author’s royalties to charity.

These conditions have been met by the majority of publishers. Harper & Row in the USA was even able to set its price at less than two dollars. However, booksellers and resellers in certain countries are negating this scheme and hurrying to profit from this unusually low price, seeking to make up the difference straight into their pockets. Now I am receiving notices from Israel that your booksellers are charging twenty-five dollars for two volumes of the Russian edition of Archipelago (sold to them for five-six dollars per volume by the feeble YMCA-Press publishing house)!

I wish to publicly declare that such brazen profiteering from this book defiles the very memory of those who perished; it is an attempt to benefit from their blood and suffering. I call upon Israeli readers to condemn these booksellers and to pressure them into giving up their shameful gains.

A. Solzhenitsyn

Solzhenitsyn did not have to include this letter, but did so anyway.

Solzhenitsyn deals most prominently with the Jewish Question, however, when chronicling his antagonistic relationship with the “Third Wave” of Soviet emigrants, who were mostly Jewish and shared little of the author’s love for the Russian people or the historic Russian nation. Chapter Seven of Millstones Book Two is entitled “A Creeping Host,” which refers not to the monolithic enemy Solzhenitsyn had faced in the Soviet Union but the “innumerable throng of petty adversaries” which he had to keep at bay once he settled in the United States. A more eye-catching, but no less accurate, title for this chapter would have been “When Jews Attack!” In Millstones Book One, Solzhenitsyn makes clear his low opinion of the Third Wave of Russian émigrés whose exodus roughly coincided with his.

But as much as I respected the First and Second Emigrations, I was indifferent to the bulk of the émigrés of the Third Wave, who were not escaping from death or from prison sentences but striving for a life that was more attractive and comfortable (though most of them left behind them privileged and well-provisioned cities, advanced education, and good positions). One could say that they took advantage of every person’s right to leave a place in which they do not want to live, but not all Soviets, not all by far, had the opportunity of making such a choice. So be it. One can perhaps only reproach them for having used the name of the State of Israel in order to leave the Soviet Union but then emigrating elsewhere. . . . Moreover, there were among them a number of individuals who had belonged to the Soviet elite and had actively served in the government apparatus of lies (and this apparatus had a broad scope: Soviet newspapers, popular songs, and the film industry). These individuals had worked closely with this apparatus. How could one define this emigration? . . . the pen-wielding emigration.

And these pens Solzhenitsyn dismisses as often being vulgar, brazen, sleazy, and mediocre. He notes how the Third Wave magazines in the West almost never had anything good to say about the previous two waves of Russian emigration — the first being the Whites who had escaped the turmoil of the Revolution and the 1920s, and the second being those who had escaped the Soviet Union during World war II and luckily had not been sent back by the Allies where murder and gulag awaited.

Solzhenitsyn also records the anti-Russian bias of many of these Jewish Third Wave émigrés. Once in the West, they seemed to wish to govern the Soviet Union from afar, believing that it, for all its faults, remained an improvement over Russia of the Tsars. This was the group of people that grew increasingly hostile to Solzhenitsyn during his exile (and vice versa). In his memoirs, one can trace this hostility back to his 1972 “Lenten Letter to Patriarch Pimen.” In Invisibly Allies, he writes how Lyusha Chukovskaya, a dear confidante with whom he had collaborated for over six years (and who once had survived an assassination attempt for her service to him), simply refused to type up the missive. She was offended by its overt appeal to Russian Orthodox Christianity, and, like Kopelev, had felt the same way about the Russian ethnocentrism found in From Under the Rubble. They both hated the Soviet regime, but somehow, Chukovskaya could not bear her friend’s spiritual atavism which seemed to appall her almost as much. Solzhenitsyn describes a particularly revealing argument of theirs:

Looking pale and drawn, not yet fully recovered — one had to wonder what was keeping body and soul together — Lyusha launched into a passionate tirade against my unspeakably shameful Orthodox-cum-patriotic orientation in From Under the Rubble. And, she added, now she understood that it was not for nothing that she had some Jewish blood in her veins.

Fast-forward ten years. Solzhenitsyn is in America, and the release of The Oak and the Calf in English had annoyed more than a few Jews, who were now smearing Solzhenitsyn in print as intolerant, theocratic, totalitarian, and, of course, anti-Semitic. Stephen Cohen in the New York Times Book Review and Max Geltman in the Jewish magazine Midstream were two of the more prominent members of this creeping host, with Geltman snobbishly asserting that Solzhenitsyn “devotes pages to his complete pedigree . . . peasants all, with the cow-dung almost bespattering the pages.” In Millstones Book Two, Solzhenitsyn states that

Even at the height of the battle at the Secretariat of the Writers’ Union, I was not inveighed against with such bile, such personal, passionate hate, as I was now by America’s pseudo-educated elite.

But this, as it turned out, was nothing.

The Vermont solitude had enabled Solzhenitsyn to update Node One of his magnum opus, The Red Wheel, otherwise known as August 1914, which had been originally published in 1972. Most offensive to the Third Wave was his inclusion of the Stolypin-Bogrov chapters [8] which told the story of Pyotr Stolypin, the great Russian Prime Minister, who was assassinated by the Jew Mordko Bogrov in 1911. Solzhenitsyn’s thesis was that only a man of Stolypin’s courage and vision could have prevented Russia’s entry into World War I, and this hope was essentially dashed when he was gunned down by Bogrov in a Kyiv theater. After shooting his victim, Solzhenitsyn describes Bogrov — as perceived by a mortally wounded Stolypin — as “wriggling away up the aisle.” Was he wriggling because he was a terrorist scoundrel trying to get away with a despicable act? Or was he wriggling because the author was indulging the anti-Semitic stereotype of the Jew as a serpent? This was the question many Jews were wrestling with in the mid-1980s, even before the revised August 1914 had been translated into English.

And, of course, they had completely forgotten about Ilya Arkhangorodsky, the wholly positive Jewish character in August 1914.

Rather, they fretted that Solzhenitsyn had depicted this Bogrov as “a Russia-hating Jewish avenger,” [9] in the words of Soviet émigré (and Jewish) writer Cathy Young. A Jewish ethnocentrist, in other words. Young is correct in her assessment of both Solzhenitsyn and Bogrov. In Millstones Book two, Solzhenitsyn defends this portrayal as corresponding with all available material on this obscure character, including the very book Bogrov’s brother Vladimir had written about the assassination. “I fought for the welfare and happiness of the Jewish people,” were the assassin’s last words before execution, according to the surviving brother.

So not only does Solzhenitsyn perpetuate anti-Jewish stereotypes, but he also blames the Jews for World War I! Of course, this is nonsense. However, the truth and Solzhenitsyn’s honest portrayal of history did little to stem the unruly and spiteful blowback which was to come.

Right away, the mainstream media began croaking out comparisons with The Merchant of Venice and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Lev Roitman of Radio Free Europe accused Solzhenitsyn of having a “racist, biological attitude towards Jews.” Vadim Belotserkovsky, also of Radio Europe, called August 1914 “propaganda for extreme anti-Semitism.” Solzhenitsyn describes the hysteria which followed as a “well-orchestrated cannonade.” The New Republic and New York’s Daily News piled on with insults and libel, with the former calling for outright censorship. The Los Angeles Times called for closer supervision of “Russian and other Soviet Bloc refugees.” The Washington Post described August 1914 as “subtly anti-Semitic,” and trotted out “experts” to weigh in on Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s anti-Semitism. Included was longtime Solzhenitsyn enemy Richard Pipes, who accused Solzhenitsyn of blaming the October Revolution on Jews.

That would be just the first brand of shame slapped onto me! — already the following day, the Boston Globe (and it was not the only one across America, you couldn’t keep track of them all) readily picked it up. It reprinted half of that same article, but tweaked the headline: “New ‘August 1914’ is alleged to have anti-Semitic tone” (but now without the “subtly”) — and the Pipes quote jumped out at you in massive type.

Solzhenitsyn dedicates nearly thirty pages in Millstones Book Two to describing the vicious and personal abuse he suffered from these people. The overall impression emerges not that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn hates Jews but that Jews — especially a large number of high-profile and influential Jews — hate him, or people like him.

As for the charge of anti-Semitism, Solzhenitsyn sees it for what it is. In a 1985 letter to journalist Richard Grenier, he writes:

As for the “anti-Semitism” label, the word has, like other labels, lost its precise meaning due to thoughtless use, and different social and political commentators over the decades have understood a variety of different things by it.

He denies that his work shows “a biased and unfair attitude towards the Jewish people as a whole,” and he also asserts that approaching “a work of literature with the yardstick of ‘anti-Semitic’ or ‘not-anti-Semitic’ is tawdriness, an underdeveloped understanding of what constitutes a work of literature.”

He is correct on both counts.

He also shows how many Jews agreed with him. During the August 1914 firestorm, one Jew in particular wrote the following to the magazine Panorama: “I am Jewish and I am sick of the accusations of anti-Semitism against Solzhenitsyn. . . . Why are Russians not allowed nationalism, while Georgians, Lithuanians, and Armenians are? Is that not racism — banning a people from having its own aspirations?”

(Again, swap “Russian” with “white” and we can see Solzhenitsyn’s relevance to today’s dissidents.)

Nevertheless, given how the anti-Semite epithet has been weaponized by Jews in order to silence their enemies, the more useful takeaway for today’s dissident would be to understand that Solzhenitsyn was not anti-Semitic, but nor was he philo-Semitic. He respected the Jewish people as much as any other ethnic or racial group, perhaps even more. But he understood that they were not his group. Solzhenitsyn’s allegiance was to his people and his nation first. While he was certainly critical of both, he had no time for the Jewish ruse of portraying non-Jews, especially white Europeans, as perennial villains. He was not afraid to place Jews in the villain role or to demonstrate their hypocrisy and tendency towards evil. All of this is supported in abundance by history and, thankfully, in many episodes found in the memoirs of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [10] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [11].

Don’t forget to sign up [12] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.