Folk:A Review

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledTony Vermont, ed.

Folk: A Collection on What it Means to be a People

The White People’s Press: 2020

It’s one thing to be part of a folk — a society connected by blood, history, myth, language, and territory. It’s something more to possess items — functional or not — that strengthen these connections. Beautiful art and great literature are two such items that have the power to bind entire nations for centuries. The editors at The White People’s Press [2] certainly understood this when they published the gorgeous coffee table book Folk: A Collection on What it Means to be a People.

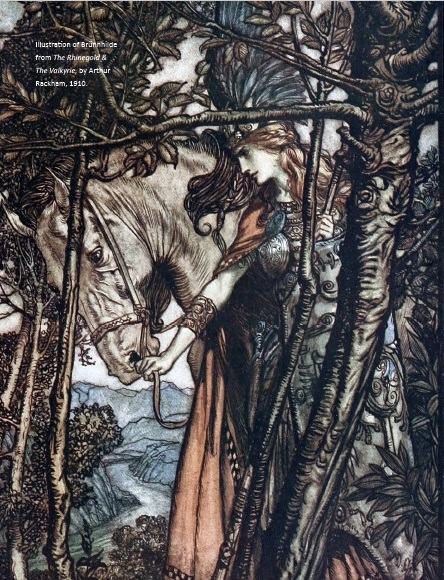

I’m afraid that words cannot do such a marvelous product any justice, but I’ll try anyway. In Folk, we have an overflowing of imagery in brilliant color which encapsulates the spirit, history, and myth which have embodied the white race for millennia and continue to do so today. Almost every page bursts with magnificent artwork. Some capture moments from pagan mythology or Christian tradition, others the poignancy of loss, the pageantry of nation, the agony of war, the struggle for survival, the keeping of tradition.

The Wild Hunt of Odin, by Peter Nicolai Arbo, the Illustration of Brünnhilde from The Rhinegold & The Valkyrie, by Arthur Rackham, and Knight at the Crossroads, by Viktor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, in particular stand out for me. But there is so much here that one can spend hours just gazing.

[3]

[3]The Wild Hunt of Odin, by Peter Nicolai Arbo, 1872, depicting the Wild Hunt in Scandinavian folklore.

[5]

[5]Knight at the Crossroads, by Viktor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, 1882. Vasnetsov depicts the hero of the Russian epic The Three Journeys of Ilya Muromets.

The photographs are equally stunning with scrapbook images and group snapshots being placed alongside vast panoramas of white civilization in its glory, both past and present:

It’s a visual feast, made richer by the overt theme of the book: that there is a unifying spirit which constitutes white people as a folk — the spirit of heroism and sacrifice, of beauty and truth, of love and war. But the selection is also somewhat idiosyncratic. A reviewer would be remiss for not mentioning the uncaptioned image on page 173 of the notorious Finger Hitler:

Eleven writers have contributed literature to this volume — twelve if you include TWPP editor in chief Tony Vermont’s Introduction, which takes us back to Aeneas’ flight from Troy and ultimately to Rome where the small band of refugees learned about what it took to build a folk and a nation. Vermont shows us how in Virgil’s The Aeneid we can find a parallel to the rootlessness and opposition that many whites are facing today:

Like Aeneas and his people, we find ourselves largely untethered to any land, wandering more with each passing generation from one fleeting wellspring to the next. And while such shifts are no anomaly to history, it is our uncertainty over our own identity that leaves us unable to overcome the crises our people now face. The Aeneid, as one scholar puts it, confronts the challenges of “forming a collective identity following the breakdown of an empire” — a description most apt, that highlights one of the many reasons Virgil’s classic Roman epic remains a particularly modern text.

[9]

[9]You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s My Mirror Tells a Story here. [10]

Jason Köhne, host of the YouTube channel No White Guilt [11], starts things off, making sense as usual. He points to the “intersection of individual and people” as the spiritual place where duty resides. He touches on how universalist thinking threatens this and deracinates whites from their past and their identities. He also demonstrates how this is the very plan of anti-whites that is currently manifesting itself most visibly in the Great Replacement. Only by answering the question “What does it mean to be a people?” can whites begin to overcome the destructive forces arrayed against us.

Jeff Winston, founder of the White Art Collective [12], offers a well-known piece of American folklore in Johnny Appleseed as an example of a legend that whites can call upon to strengthen ties to one another. Winston gives us a brief biography of Johnny Appleseed (real name, John Chapman), and places him in the context of the early days of the United States when true American myths and legends were in short supply. Through his noble spirit, his love of nature, and his planting of apple seeds along his broad peregrinations, Johnny Appleseed has had a lasting and positive impact on the white American people.

Ilenia, the young Italian who operates the Nordic Beauty [13] Tumblr page, provides an ingenious linguistic perspective on the question of folk. For example, she describes that the Italian word popolo which means “a multitude of people living in a specific territory, following the same Law and belonging to the same race,” could be derived from the Latin populus, meaning to reunite or put together. But she also pursues a more interesting line of thought:

On the other hand, historians like Theodor Mommsen and Arnaldo Momigliano see in popolo a derivation from the proto-Italic and Osco-Umbrian word poplos, which means “army.” Similar to this, in Latin, the root of the verb populo with the suffixes -as, -are, -aris, or -ari mean to devastate, to destroy, to leave devastated, and is therefore linked to the idea of war conducted by an organized military force. This would make a popolo not only a group of similar people moved by similar interests, but a group of people ready to protect themselves and what they represent through force.

She demonstrates how Latin is filled with fascinating linguistic clues on what it means to be a folk.

A more humorous and anecdotal approach comes from Australian YouTuber Lovely Porridge [14], who starts his chapter on Australian folkways with a hilarious joke (“An Englishman, a Frenchman and an Australian are traveling through a desert when they are suddenly surrounded by a tribe of angry Natives holding spears. . .”) Mr. Porridge provides a brief history of the white colonization of the continent by supposed “convicts” from the British isles. He also offers a clue to the culture shock these penniless Anglo-Saxons must have felt when entering a land as dry, dusty, and wild as Australia. This and the fact there is gold in them thar deserts did much to mold a unique (and quite endearing) Australian character:

Maybe Aussie self-deprecating humour came about because it was hard to take yourself too seriously when a snake could send you running and screaming from the outhouse with your pants between your ankles.

Sadly, he notes how when the modern Australian intelligentsia makes fun of Australians, it’s not in a self-deprecating way, but in a cruel, disparaging way. He also notes how his homeland has lately begun to sink into the rot of anti-white racism and political correctness, but vows that the tough, independent spirit of his people, which overcame a wild continent, will overcome this as well.

Folk also contains a foreword by Ricardo Duchesne, a short story by Jared George which takes place in a positive white future, and essays by Laura Towler, E. Chars, Liv Heide, and John Bruce Leonard.

The standout essay of this collection is also its longest. Counter-Currents contributor and author Ash Donaldson [15] utilizes his vast scholarship in “Elements of a Folk.” Few people think as deeply or as comprehensively as Donaldson on this topic. With his intimate understanding of Norse and Germanic mythology, sagas, and languages, he offers a systematic and, what’s more, useful, understanding of the concept of folk. He describes “folk” as people who are bound by history, language, religion, but, most importantly, blood.

He certainly practices what he preaches. A review of his own roots stretches back centuries (one of his Scottish ancestors died fighting the English at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547). And it is this crucial understanding of — and reverence for — our roots which give a folk character and life:

When the family is uncoupled from biological continuity, as in modern attempts to re-imagine it, the home becomes no more than a boarding house: people come, stay for a while, then leave, but they possess no underlying connection besides the physical occupation of the same general space. Likewise, without common ancestry, there is no folk, only a population that happens to inhabit roughly the same geographic area. The rulers of such a populace, in order to govern, must fall back on ideology. The contrast between a folkish view and an ideological one was seldom so clear as during the height of the French Revolution, when the folk of the Vendée region were being put to the sword for holding on to their ancient traditions. The nobleman François-Athanase Charette, who led his people against the revolutionaries, put it this way:

Our country is ourselves. It is our villages, our altars, our graves, all that our fathers loved before us. Our country is our Faith, our land, our King. . . But their country — what is it? Do you understand? Do you? . . . They have it in their brains; we have it under our feet. . .

So blood becomes the necessary but not sufficient condition for a folk. After all, millions of whites have related ancestry, but do not necessarily constitute a folk. In fact, many whites have become enamored with (and controlled by) an ideology that may be more inherently anti-folk than anti-white. By displaying his customary wealth of knowledge on matter literary, mythical, and historical, Donaldson prescribes returning to our legends, our myths, and our languages to combat this insidious malaise. Only then can whites reclaim their collective identity and be strong once again as folk.

This collective identity theme flows in varying ways through every page of Folk, regardless if the reader cares to drill down into the writing or simply take in the gorgeousness of the images, including those of the front and back cover. This is really what a coffee table book is meant to be: elegant, decorative — on top of all of its other virtues. Books do furnish a room, but Folk does more. It furnishes a home, a home that is connected to other homes, which together constitute the eponymous entity of this wonderful volume.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [16] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [17].

Don’t forget to sign up [18] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.