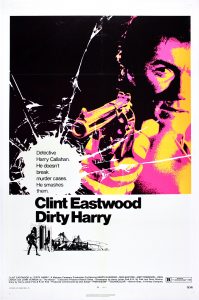

Dirty Harry

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledDirty Harry (1971), directed by Don Siegel and starring Clint Eastwood as San Francisco Police Inspector Harry Callahan, is a classic of Right-wing cinema. Dirty Harry was hugely popular with moviegoers, spawning four sequels and a whole genre of films about tough cops whose hands are tied by the system and are forced to go outside the law in order to protect the public.

Dirty Harry articulated the growing reaction to the racial unrest, hippy degeneracy, and liberal mush of the 1960s, which led to skyrocketing crime in American cities and white flight to the suburbs. Liberalism holds that society can be ruled by impersonal laws, not men. Thus any film giving a favorable view of vigilantism — in which laws break down and individuals take justice into their own hands — is anti-liberal.

Dirty Harry was seen as a reactionary film at the time. Paul Newman declined the title role because he thought it too Right-wing. Feminists protested outside the Academy Awards with a banner reading “Dirty Harry is a Rotten Pig.” Thus I found it surprising that Dirty Harry was viewed favorably by leading critics, most of whom were liberals and Leftists. For instance, Pauline Kael [2] recognized the film’s technical merits and emotional power but decried it as “fascist,” “a remarkably singleminded attack on liberal values,” and “a deeply immoral movie.” Dirty Harry ended up in many “Best” lists, including the New York Times’ top 1000, Empire magazine’s top 500, Total Film’s top 100, and TV Guide’s and Vanity Fair’s top 50.

I can’t include Dirty Harry in any of my best lists, but it is still a remarkably good film, with compelling lead characters, a gripping plot, and a tight script. Filmed on locations in and around San Francisco, with creepily effective music by Lalo Schifrin, Dirty Harry captures the beginning of the long, seedy cultural hangover of the ’60s, imbuing it, if not with a glamour, at least with a gloss, bad haircuts and all. Clint Eastwood as Harry Callahan and Andy Robinson as the loathsome villain Scorpio give excellent, compelling performances.

Harry Callahan is another one of Eastwood’s taciturn Aryan heroes, a physically imposing and highly capable alpha male who becomes a protector of public order. Like most of Eastwood’s classics, the world of Dirty Harry is divided into sheep, the wolves who prey on them, and the sheepdogs who protect the flock, to borrow a scheme from American Sniper. However, despite their opposed roles, wolves and sheepdogs have more in common with each other than they do with sheep, and the flock starts bleating nervously when the dogs bare their fangs at the wolves.

Harry Callahan is 40ish. (Eastwood was 41 in 1971.) He is an Inspector for the San Francisco Police Department, a position of responsibility that requires intelligence. He is contemptuous of college boys, so he probably came up through the ranks. He is a widower. His wife was killed by a drunk driver. He does not appear to have children. His work is his life now. He probably also harbors a death wish, or at least an indifference to his own interests, which makes him more effective at doing his duties. Because Harry is more driven than other cops, he prefers to work alone. Partners tend to slow him down and get wounded or killed.

Callahan is not called “Dirty” Harry because he is a corrupt cop. He is Dirty Harry because people trust him to do dirty jobs. He gets “the shit end of the stick.” Dirty work means actually confronting criminals. Sometimes you get dirt on your hands. Sometimes you get blood. Sometimes you have to go outside the law to enforce the law.

The clean jobs are reserved for the city government and police brass, whose biggest worries are lint and bad press. Their jobs are to demand results from their underlings then second-guess their every move. Dirty Harry is a populist hero because he is the stoic, competent white Atlas who carries the system on his shoulders but is also treated as deplorable and expendable by the elites.

Harry is also supposed to be dirty because he is a hater: “Harry hates everybody: Limeys, Micks, hebes, dagos, niggers, honkies, chinks.” To which Harry adds for the benefit of his new Mexican-American partner Chico Gonzalez (this movie is not exactly subtle), “Especially Spics.” Dirty Harry didn’t just pioneer the loose cannon cop genre, it also established the convention of pairing these white alpha males with non-white sidekicks. (A white alpha male mentoring another white man as a guardian of society would make Don Siegel hallucinate the sound of marching feet.) However, if Harry hates honkies, he can’t be a white racist. And if his name is Callahan, that makes him a self-hating Mick. In truth, Harry is merely a detective. He’s trained to notice patterns [3]. That makes him politically incorrect.

Harry has more than just a touch of sadism, which is brought out in the movie’s most quoted scene. During his lunch break, Harry foils an armed bank robbery by three blacks, killing two with his .44 Magnum and wounding the third, whom he taunts:

I know what you’re thinking: “Did he fire six shots or only five?” Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I’ve kinda lost track myself. But being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and would blow your head clean off, you’ve got to ask yourself one question: “Do I feel lucky?” Well, do you, punk?

[4]

[4]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here. [5]

When Harry repeats the same taunt almost word-for-word at the end of the movie, the effect is chilling. You glimpse a bitter, sadistic side of his character. You wonder how many times he has done this. He clearly enjoys killing scum. Hence his preference for pistols that can decapitate and rifles that can stop elephants.

The plot of Dirty Harry is a standard neo-noir police thriller. Harry’s quarry is a serial killer, Scorpio (based on the Zodiac killer). Scorpio was so effectively brought to life by Andy Robinson that the actor received death threats and had to change his phone number.

Scorpio is a Dostoyevskyian criminal Untermensch. He’s physically weak, unmasculine, and cowardly, palpably seething with resentment. He squeals like a pig, blubbers like a child, and develops a severe limp after Harry stabs then shoots him in the leg.

Scorpio is attracted to weak victims: a young woman in a swimming pool, a couple of homosexuals, a ten-year-old black child, a Catholic priest, a teenage girl, an old man, a bus full of schoolchildren, a little boy fishing. He prefers to kill like a coward, shooting two victims with a sniper rifle, burying another alive.

Two scenes are especially repulsive. Scorpio has kidnapped, raped, and buried a teenage girl alive. She is running out of air. Harry tracks him to his lair and doesn’t wait for a warrant. He just kicks in the door. Pursuing Scorpio out onto the field of Kezar Stadium, Harry brings him down with a .44 shot to the leg, then stamps on the wound, demanding to know the girl’s location while Scorpio shrieks “I have rights. I have rights.” If you have any doubt about where a person falls on the F scale, just show him this scene.

Of course, Scorpio is released because Harry didn’t follow proper procedure. His defense was that a girl was dying, so there really wasn’t time for a warrant and a genteel interrogation. But that doesn’t matter to the Jewish DA and the Berkeley Law professor he consults. Scorpio had rights. Harry violated them. So all of society must be punished. When healthy people watch this scene, their blood boils.

Harry, of course, won’t let this drop. He begins to shadow Scorpio in his spare time, hoping to prevent him from killing again. Scorpio is repulsive with his long hair, gimp, and fruity hippy rags, including a grotesque peace sign belt buckle. As he wanders around parks and playgrounds looking at small children, your blood will run cold.

When Scorpio realizes he is being shadowed, he doesn’t confront Callahan or go to his superiors. Instead, he pays a black thug $200 to beat him to a pulp, then blames it on Callahan. This sequence is a viscerally powerful critique of modern liberal slave morality which rewards and weaponizes victimhood, creating an incentive to fabricate police brutality and hate crimes.

Dirty Harry’s final act after bringing Scorpio to justice is to take his badge and throw it away. John Wayne refused the role because he thought this gesture “un-American.” Eastwood did not want to do it either but came to see the logic of it.

Harry has been living the zone of what Carl Schmitt called the “Ernstfall [6],” the emergency situation in which the reigning liberal norms are not capable of securing justice. Faced with the choice of law or justice, Harry chooses justice. It is the first step down the path to the vigilante — or the superhero [7]. The gesture, however, is wasted. Instead of evolving into something higher, Harry Callahan is sucked into the Eternal Recurrence of the movie franchise. But his viewers don’t have to be.

Dirty Harry turns fifty this year. Judging from the film, San Francisco was just as degenerate half a century ago as it is today. The main difference is that there are no adults like Harry Callahan to keep it together anymore. One has to ask: How much more ruin is left in this country before it all falls apart? Is anyone up to the dirty job of putting it back together again?

The Unz Review [8], January 30, 2021

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [9] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [10].

Don’t forget to sign up [11] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.