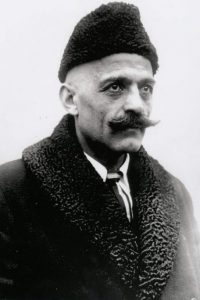

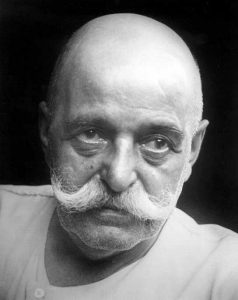

Remembering Mr. Gurdjieff: January 13, 1866/1872/1877–October 24, 1949

Posted By Collin Cleary On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled7,589 words

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was born on this day in 1866, 1872, or 1877 — depending on whom you ask. [1] [2] Much else about his biography is equally uncertain. We do know that his father was Greek, his mother Armenian, and that he was born in Alexandropol which was then part of the Russian Empire (it is now in Armenia and is called Gyumri). When he was still a young man, Gurdjieff spent close to twenty years traveling to such exotic locales as Central Asia, India, Iran, Egypt, and Tibet on a search for hidden knowledge.

These years are depicted in Gurdjieff’s most accessible book, Meetings with Remarkable Men (published posthumously in 1963). However, the book mixes probable fact with evident fiction, and is full of tall tales. After encountering many teachers and fellow seekers, Gurdjieff claimed to have wound up somewhere in Asia at the monastery of a secret organization called the Sarmoung Brotherhood, where he was initiated. Although it is certain that esoteric knowledge was transmitted to Gurdjieff, there are absolutely no other sources attesting to the existence of the Sarmoung Brotherhood.

After this supposed initiation, Gurdjieff returned to the West, settling first in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1912, then in Moscow in 1914. There he began to gather around him a circle of followers, all highly accomplished individuals. They included the journalist P. D. Ouspensky (1878–1947) who would later write the most popular and enduring introduction to Gurdjieff’s ideas, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. Another associate was the composer Thomas de Hartmann (1885–1956) with whose aid Gurdjieff composed a large number of musical compositions (generally known as the “Gurdjieff-de Hartmann music”).

When the Bolshevik plague swept Russia, Gurdjieff and his followers fled the country, leading a nomadic existence full of adventures (which make for exciting reading: see Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff by Thomas and Olga de Hartmann). Eventually, they wound up in France, where, in 1922, Gurdjieff founded the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at the Chateau du Prieuré at Fontainebleau, near Paris. It was at Fontainebleau that Gurdjieff and de Hartmann produced their famous collaborations (many quite beautiful), and that Gurdjieff began teaching the “movements,” which are rather inadequately described as a form of “dance.”

After a car accident that almost claimed his life, Gurdjieff shut down the Prieuré in 1932 and moved to Paris. He remained there for the rest of his life, making occasional trips elsewhere in Europe and to the US to stage demonstrations of the movements, and to solicit financial support. (Gurdjieff was perpetually broke, but also boundlessly resourceful, and generally managed to live quite well.) Much to everyone’s surprise — but probably not his own — he died in Neuilly-sur-Seine on October 24, 1949.

What did Gurdjieff teach, and why has he been so extraordinarily influential?

[3]Like the philosophy of the Buddha, Gurdjieff’s teaching can be imparted in a series of theses or “noble truths.” The first of these is that man is asleep. This is a perennial observation, found throughout the history of philosophy, East and West. For example, Heraclitus (fl. 500 BC) wrote that “One ought not to act and speak like people asleep.” And: “For the waking there is one common world, but when asleep each person turns away to a private one.” [2] [4] (See my essay “On Being and Waking” in Tyr Vol. 5 [5].)

[3]Like the philosophy of the Buddha, Gurdjieff’s teaching can be imparted in a series of theses or “noble truths.” The first of these is that man is asleep. This is a perennial observation, found throughout the history of philosophy, East and West. For example, Heraclitus (fl. 500 BC) wrote that “One ought not to act and speak like people asleep.” And: “For the waking there is one common world, but when asleep each person turns away to a private one.” [2] [4] (See my essay “On Being and Waking” in Tyr Vol. 5 [5].)

Almost all men go through life in a state that is a kind of waking sleep. And even the ones who do manage to “awaken” still continue to spend a great deal of the time asleep. To see the truth of Gurdjieff’s claim, just reflect on how much of the time you are “not there” for the things that happen in your life. I look forward all day to the dinner I plan to cook. Then I eat it but take little enjoyment in the act, barely able to remember later that I ate at all. Why? Because throughout the entire meal my mind was working mechanically, ruminating over my recent difficulties and complaints.

Gurdjieff maintained that it is actually extremely hard to convince others that they are asleep. One of the reasons for this is that being presented with the claim “man is asleep” actually has the effect of shocking people, briefly, into wakefulness. Thus awakened, a man will fiercely deny that he is one of the sleeping people, one of the cattle. Moments later, of course, he will slip right back into unconsciousness, slumbering contentedly in the belief that he has dealt handily with this Gurdjieff stuff.

The second “noble truth” of the Gurdjieff teaching is that man is not one. I think that I have one, single “I.” But Gurdjieff insists that I do not. In fact, I have many “I”s. How can such a strange claim ever be made plausible? Well, let us consider the claim that I just made: “I think that I have one, single ‘I.’” But to reflect on my “I” — the “I” that I “possess,” that I think is “mine” — I must split into two. There is this “I” am reflecting upon, which I take to be my “personal identity,” but then there is the “I” that reflects upon it. This one observation constitutes a rigorous philosophical demonstration that there is more than one “I” in me.

All right, I am willing to accept that there are two “I”s, what is “me,” my “ego, “my self,” and what reflects upon this and says things like “I like myself,” or “I don’t like myself,” or “I am growing as a person,” etc. But is it plausible to think that there are many “I”s? Well, observe that on any given day one might say “I like myself; I am satisfied with myself.” The following day, “I” may claim the opposite — that I am really a “bad person,” and really believe it. One evening I may torture myself with bad memories, with feelings of guilt or regret. I may cry “enough!” at a certain point and try to banish these. But after a moment, the thoughts return. Who is doing this? Who is this “I” of the moment that seems perversely determined to torture “me”?

Or: I have an appointment with the dermatologist to get that spot on my face checked out. But I oversleep, having for the first time in years failed to set my alarm, and it is now impossible for me to get to the appointment. I curse “myself.” Then I realize that clearly “I” deliberately sabotaged the day, out of anxiety over what the doctor might find. But who did that? It was not the “I” that woke up in consternation, unable to understand why “I” failed to set the alarm.

Now, one might plausibly respond to Gurdjieff by saying that these examples do not support the idea that there are multiple “I”s. Instead, they support the idea that there are multiple “aspects” to “myself.” For example, the difference between the day on which I like myself and the day on which I don’t is just that the “I” was in different “moods.” As to the supposed mystery of what “I” maliciously tortures me with negative thoughts and refuses to let up, well, that is just “the subconscious.” And it was “the subconscious” that caused “me” not to set the alarm and to miss the appointment.

But consider how vague, how really vacuous our notions of “mood” and “the subconscious” are. Consider also that when I insist on a unitary “I” that “has” all these “aspects,” I am operating implicitly with a certain set of metaphysical presuppositions. Obviously, I am assuming, first of all, that there is one and only one “I”: my “self,” my “personal identity.” Second, I am assuming that this “I” is sort of like a box. Inside the box are moods, subconscious this and that, emotions, memories, thoughts, expectations, etc. These are all “contained” within “me.”

Gurdjieff asks us to challenge this folk metaphysics of the mind. In doing so, he comes rather close to what David Hume said about the “self” in his Treatise of Human Nature:

For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception. When my perceptions are remov’d for any time, as by sound sleep; so long am I insensible of myself, and may truly be said not to exist. And were all my perceptions remov’d by death, and cou’d I neither think, nor feel, nor see, nor love, nor hate after the dissolution of my body, I shou’d be entirely annihilated, nor do I conceive what is farther requisite to make me a perfect non-entity. If any one, upon serious and unprejudic’d reflection thinks he has a different notion of himself, I must confess I can reason no longer with him. All I can allow him is, that he may be in the right as well as I, and that we are essentially different in this particular. He may, perhaps, perceive something simple and continu’d, which he calls himself; tho’ I am certain there is no such principle in me. [3] [6]

[7]

[7]You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here [8].

In other words, when I “enter most intimately” into “myself” I never find any thing I can call “myself.” Instead, I find this perception or that, this emotion or that, etc. I find no unitary “self”; I find only a multiplicity of “ideas.” One finds a similar view in Buddhism. When the legendary sage Bodhidharma journeyed to China, a man came to him and said “I have no peace of mind. Please help me pacify my mind.” Bodhidharma responded, “Bring out your mind and I’ll pacify it for you.” The man responded, “Well, that’s the problem. When I look for my mind I cannot find it.” “There,” replied Bodhidharma, “I have pacified your mind.” [9]

When Gurdjieff insists that we have multiple “I”s he, like Hume and Bodhidharma, is simply being a good phenomenologist. It is a tall order, but let us try to set aside all habitual metaphysical assumptions about the one, boxlike “I” that “contains” all that is “me.” And then let us simply describe our experience. If we do, we will find that it certainly seems like there are multiple “I”s; that there are different “me”s that come and go, each clearly armed with its own agenda. How does Gurdjieff evaluate this multiplicity? Well, negatively, of course. We are torn apart by these many “I”s; torn in different directions by their different agendas and claims on us. The ideal would be, somehow, to achieve the very thing we falsely think we already have: one, unitary “I.”

So, what can we do about all of this, about our state of sleep, and our lack of a real “I”? Well, those who ask this question are in for a letdown, since the third “noble truth” of the Gurdjieff teaching is that man can do nothing. This pessimistic claim, which Gurdjieff doggedly insists upon, is liable to produce an even more indignant response than the claim about man’s sleep. “Indignant” is exactly the right word, for the assertion that we can do nothing seems an affront to the dignity of man. If we cannot “do” anything then aren’t we unfree? In the end, Gurdjieff will ask us to rethink freedom and dignity. We must ask, does freedom consist in “doing,” or in something else?

There is a way out of the pessimism posed by Gurdjieff’s claim that we can “do” nothing, but we will need to come to this in a roundabout way. For now, let’s return to the idea that man is asleep and consider more carefully just what “sleep” really means. Earlier, I gave an example in which the mind works “mechanically.” The key Gurdjieffian term for understanding sleep is, in fact, “mechanicality.” Our sleep consists in the fact that we behave mechanically; we behave like machines. We think, feel, work, play, walk, talk, and make love like automata programmed with a certain repertoire of behaviors that we simply repeat over and over again.

This is usually presented in the Gurdjieff teaching as if it is a timeless observation about human nature. In fact, however, men could not behave like automata until automata were invented. An automaton is a machine designed to give the appearance of self-generated action. Such machines were known in the ancient world, where they were mainly used as toys. None has survived to the present, and many stories about ancient automata may be pure legend. It was not until the modern period that the building of automata became widespread and highly sophisticated. Such machines were so widely known by the seventeenth century that when Descartes was looking for a way to describe the difference between human beings and animals, he likened animals to automata.

Malebranche was speaking for Descartes when he wrote of animals, “They eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.” [4] [10] At the same time, while Descartes insisted on the reality of a free and immortal human soul, he claimed that our bodies, by contrast, should be understood as machines. He writes in the Meditations,

A badly made clock conforms to the laws of its nature in telling the wrong time, just as a well-made and accurate clock does; and we might look at the human body in the same way. We could see it as a kind of machine made up of bones, nerves, muscles, veins, blood and skin in such a way that, even if there were no mind in it, it would still move exactly as it now does in all the cases where movement isn’t under the control of the will or, therefore, of the mind. [5] [11]

Thus, for the first time in the history of Western thought, technological productions are employed as models for understanding nature, and human nature. This way of thinking is still with us today, indeed it has only intensified. With the elimination of the idea of the soul, man is now nothing but machine. This should not be seen specifically as a development in modern philosophy. Instead, philosophy has followed a broader cultural trend in which technology has progressively come to dominate life, and our thinking about life. We reached a point some time ago where human beings began not only to conceive of themselves as machines, but, inevitably, to behave like them.

When Heraclitus tells us that the ordinary, unreflective man is “asleep” he does not mean that he acts like a machine. Other early Greek philosophers disparage the common folk as well, but never in the language of mechanicality. Heraclitus also says that ordinary people “put their trust in popular bards and take the mob for their teacher, unaware that most people are bad, and few are good.” [6] [12] Parmenides calls them “deaf and blind alike, hordes without judgment.” [7] [13] Plato depicts such men as in a cave. There they are not blind, but they see only shadows, and never wonder whether there might be something more.

So, for the ancients, that men are “asleep” means that they do not see truth because they do not exercise independent judgment, and instead conform to what authority figures or “they” say is true or real. The ancients never denounce “mortals” because they are machine-like; because they repeat the same actions or words over and over again, without any awareness that they exhibit these patterns. Thus, Gurdjieff’s teaching is directed against a “sleep” that is peculiarly modern. It is also peculiarly Western (though the disease is spreading widely and rapidly), and Gurdjieff consciously and explicitly offers his teaching as a path for Westerners.

Another modern, Western peculiarity is the idea that we can always “do” something — indeed, that we can do everything and anything. We believe that everything is fixable and manipulable. So, quite naturally, when we hear that we behave like machines we automatically think that we can simply choose to be otherwise. We think of ourselves as thinglike — indeed, as a mechanism that isn’t functioning correctly. Gurdjieff alerts us to our mechanicality, and we hear this as “The mechanism is being ‘too mechanical.’” Well then, let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work! Perhaps we can formulate a plan or a method or twelve-step program for tweaking the machine and making it “less mechanical.”

[14]In insisting we can “do something” about our mechanicality we thus think mechanically — immediately falling into ingrained, modern ways of thinking and acting. And we implicitly affirm the idea that we are a mechanism! In short, our first response on being told of our mechanicality is . . . more mechanicality. But, as we have already seen, Gurdjieff tells us that we can “do” nothing about this. With this claim, he strikes at the heart of modernity. Is there, then, no hope? Should we wait for a god to come along and save us? In fact, there is hope, but it will consist in something other than “doing.”

[14]In insisting we can “do something” about our mechanicality we thus think mechanically — immediately falling into ingrained, modern ways of thinking and acting. And we implicitly affirm the idea that we are a mechanism! In short, our first response on being told of our mechanicality is . . . more mechanicality. But, as we have already seen, Gurdjieff tells us that we can “do” nothing about this. With this claim, he strikes at the heart of modernity. Is there, then, no hope? Should we wait for a god to come along and save us? In fact, there is hope, but it will consist in something other than “doing.”

In the past, men followed certain “spiritual paths” to awakening, to the overcoming of sleep. But Gurdjieff maintains that these paths no longer work well for us in the modern world; they are no longer appropriate to our situation. He identifies three such earlier paths or “ways,” that of the fakir, the monk, and the yogi. Each of these concentrates on developing or controlling one of the three human “centers” identified by Gurdjieff: respectively, the moving-instinctive, emotional, and intellectual centers. These “ways” not only tend to cause practitioners to develop only one side of themselves, they also usually require that practitioners separate themselves from ordinary life in special centers, schools, or ashrams. Thus, they are impractical in modern, Western life.

Instead, Gurdjieff teaches “the fourth way.” This path combines elements of the other three. More important, however, is the fact that it is lived in the midst of life, not in separation from it. Gurdjieff’s teaching presents the possibility that we can live in the modern world without being overcome by the forces that lead others to “sleep.” Indeed, Gurdjieff teaches that the modern world provides us with invaluable material for use in “work on oneself.” One can learn to use this material, rather than be dominated or corrupted by it, if one follows what he called “the way of the sly man.” In this respect, the fourth way is indistinguishable from what is called in other schools the “left-hand path.”

So, how does one practice the fourth way? Note that a moment ago I used the Gurdjieffian expression “work on oneself.” Within his school, the expression “fourth way” is actually seldom used. [8] [15] Instead, the practice Gurdjieff brought is referred to as “the Work.” An individual who is involved with a “Gurdjieff group” is said to be “in the Work.” This might make some readers immediately think of the “great work” or magnum opus of alchemy. This is an extremely useful association to make, for the Gurdjieff Work really is a kind of alchemical transformation. At the risk of oversimplification, the Work is a process of transmuting the lesser ego or self with which we identify into a “higher” Self. This is a good place to begin, although, as we shall see, ultimately all such language has to be abandoned.

As to the exact nature of what is involved in the Work, for many years the texts produced by Gurdjieff’s followers (and by Gurdjieff himself) were extremely cagey about this. They often insisted that the specific exercises employed in the Work could only be communicated by a teacher, in a group. There were very good reasons for this. For example, Gurdjieff often tailored exercises to specific individuals, and what was appropriate for one individual might not be appropriate for another — indeed, might even be harmful. However, in recent years many books have been published which detail the central practices involved in the Work, and even many of the exercises imparted by Gurdjieff and his closest associates.

At the most basic level, we may say that the Work involves a kind of “seeing.” The fourth (and final) of the “noble truths” I shall name is see all this. See what? See that we are asleep, see that we are not one, see that we can do nothing. Man is asleep. Man is not one. Man can do nothing. See all of this. That is enough to begin. Everything else in Gurdjieff’s teaching follows from the first three claims, plus the command (or invitation) to “see.” The imperative of “seeing” is continually emphasized by those trained in Gurdjieff’s ideas. However, this use of “seeing” is metaphorical. In what follows, I will focus specifically upon seeing mechanicality, because that is a very important first step.

What exactly does it mean to “see” my mechanicality? First of all, I can be mechanical in countless ways. My thinking may be mechanical. I may exhibit certain automatic thought processes — such as engaging in “either-other” thinking, or “catastrophizing.” I may remain largely unaware of these. And even when these patterns are exposed, I am not cured: I will continue to fall into the same habits. What can I do about this? Remember: one can do nothing. The very fact that these patterns keep showing up, even after I have seen them and firmly resolved to change, is confirmation of this. However, while I may not do, I may continue to see. Indeed, I must continue to see those mechanical thoughts when they come up. Of course, I will not always succeed in catching them and seeing them. I may go an entire day — or week, or month, or even a year (or more) — behaving according to my old thought patterns, and then suddenly “wake up” and realize that I have been asleep, slumbering in my mechanicality.

Just as there is mechanical thinking, so there is mechanical . . . everything. My emotional responses may be mechanical. My conversation may be mechanical (e.g., telling the same stories over and over or uttering the same quips when certain subjects come up, each time pleased with my “quick wit”). My movements may be mechanical. My sexual responses may be mechanical. And so on; the possibilities are limitless. To “see” all this mechanicality obviously has nothing to do with vision. If we search for another word to explain “seeing” we might say that we are “registering” our mechanicality. But what does that mean? Well, it does not mean to make a mental note. It does not mean that words enter my head and that my intellect recognizes something. For instance, it does not mean that I say to myself “I’m doing it again. That’s the third time this week I’ve told that joke.”

Why is “seeing”/“registering” not an intellectual activity? The primary reason is that the intellect itself is one of the things that is seen or registered. If the intellect is not the seer but the seen, then what is it that sees? Here we enter into the realm of mystery. Those in the Work will sometimes speak of a higher Self that does the seeing. However, Gurdjieff himself seldom spoke this way. (How the Work has changed since Gurdjieff’s death in 1949 is a controversial topic; one element is that there seems to have been an influence of Vedanta on how the Work now gets conceptualized.) Further, if a “Self” is involved, it is unlike any with which we are acquainted. So why continue to use the language of subjectivity?

At this point, to advance further in understanding what “seeing” is, let me ask the reader to perform a simple exercise (which does not come from Gurdjieff, but a different, related source). While seated, extend one of your arms out in front of your body in a relaxed posture, touching nothing. Now, without changing the position of the arm, close your eyes and ask yourself “How do I know my hand is still there?” You are not allowed to open your eyes. And it will not suffice merely to note that you remember putting your arm out and that you know you haven’t moved it since then. How, then, do you know it is still there? If you take the exercise seriously, you should soon begin to feel or to sense the hand — even though it is not touching anything, and you are not touching it with your other hand. Most people report that their hand begins tingling. They are generally surprised by the amount of tingling and “nervous energy,” for lack of a better term, that they feel in the hand.

Now, this tingling has not been caused by the exercise. It was there prior to the exercise — you were simply not aware of it. Your entire body is tingling and alive all the time, you are just not usually open to this experience. This exercise is an example of “seeing” or what is called in the Work “self-observation.” The hope that Gurdjieff offers us consists just in this practice. This may seem like a raw deal: so what if I can “see” my mechanicality, if it never changes? But the act of seeing will cause mechanicality to change, though often this takes a very long time. As I start to see my habits more and more, they gradually begin to lose their hold on me. For example, I might notice that I feel more anxious earlier in the day, and that I have a tendency to ruminate over problems that, a few hours later, may seem positively silly to me. So long as I do not see this habit I will remain in its power. But if I can come to see it — and to see it again and again and again — I will enter into a new phase in my relation to the habit. When it rears its ugly head again, I will reach a point where I greet it with a quality of resignation and detachment: “Oh yes, there it is again.” And while the habit does recur, it ceases to have the same hold on me. Eventually, it may disappear entirely.

Nitpickers will complain that “seeing” really is a type of “doing.” But in insisting that this is not the case, Gurdjieff has hit on something very important about seeing. It is not an act of changing anything, or manipulating anything. Indeed, teachers in the Work emphasize that we must see without trying to change, even when what we see (in ourselves, for example) is unpleasant or somehow undesirable. Seeing is, fundamentally, a kind of openness. For this openness to happen, “I” have to “withdraw.” “I” simply open, or allow openness. I do not act to effect change in what is seen in this openness. The will to change is always driven by the “I” and its plans and projections, and that is what Gurdjieff means by “doing.” So, the distinction he makes is quite real and valid: “seeing” is not a type of “doing.”

Given the above discussion of how seeing our mechanicality can change it, we will recognize that the Gurdjieff Work can off us some serious “self-help.” This “seeing” we have described is roughly equivalent to what is currently being marketed as “mindfulness” by the self-help industry. However, those in the Gurdjieff Work are adamant that it is not about self-help. The reason for this is simple. Whatever my plans for self-improvement may be, they are always drawn up from the standpoint of some particular “I” or other, and its agenda; its peculiar fixations and limitations. We are not seeking, in the Work, to meet the needs of those selves or to satisfy them. We are seeking to go beyond all that — to go beyond the current standpoint of what I think is “myself”; its values, beliefs, goals, and, most especially, its “self-image.”

I have friends who resist the Gurdjieff Work, or teachings such as those of Buddhism, because they have a knee jerk reaction against the language of self-abnegation. Some of them tell me that they are quite happy with themselves, on the whole, and have no desire to “annihilate the ego.” With most people, however, it is axiomatic that the more satisfied they are with themselves the more that self cries out for “annihilation.” But the result of the Work is not that one becomes a void without personality or emotions. In fact, one comes to be more “there,” more present, and more alive. What is “annihilated” are the self-limiting aspects of the ego that make growth difficult or impossible. Should one speak then not of “going beyond” the ego or “annihilating” it but rather of, for example, “growing” or “expanding” the ego? Perhaps. But probably not. (After all, which ego do we mean?)

[16]

[16]You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune? here [17]

For those who really do the Work, and do it for many years (because it takes many years), the change can be so radical that one might as well speak of ego annihilation. Besides, to speak merely of “changing” the ego is a way that ego can safeguard itself and its petty fixations. To see, as I have said, is to open, and to open is to open to the unknown. This includes what I do not know about myself, and may never have faced. And it includes potentialities for transformation that we cannot possibly know in our present state. This is exciting when you read about it in a book. When you actually come to practice this path, it can become threatening and even terrifying. This is the primary reason that paths such as the Gurdjieff Work are resisted and often ridiculed and dismissed.

To see one’s mechanicality is merely a first step and, as I hope I have already made clear, it is a difficult one. But it is the only way to come, truly, to an understanding of what Gurdjieff means when he says that we are asleep. Of course, it is not just mechanicality that we must see. I have also mentioned that we try to see that we are not one, and that we can “do” nothing. But as my exercise involving the hand indicates, seeing can also be directed at very simple and delimited “objects,” such as the present state of a part of the body, a specific emotion or reaction, etc. I have already said that seeing can be understood as “openness.” What does one open to? The simplest answer to this question is everything.

The Gurdjieff Work speaks of “dividing attention” between oneself and objects in the world. For example, I look to my left, to a black pen that lies next to my computer. I look at it, and I place two fingers on the end of the pen. I open to the reality of the object, to the sheer thereness of this thing. And simultaneously I open to what this object brings up in me — to whatever thoughts or emotions it occasions. I open to the physical sensation of the pen under my fingers, to the gleam of light reflected on its glossy, plastic case. I open to all of this, and I simply watch. Again, it is not intellect that engages in this very special sort of attention, for this attention sees the intellect as well (e.g., the stray thoughts that the pen occasions). In the Gurdjieff Work, the aim is simultaneous awareness not just of “object” and “subject,” but of all the centers of the “subject” — intellectual, emotional, moving-instinctive, at the same time.

But now we come to a very basic question, neglected in what has been said so far: why do this? Why aim for this? Why do the work? As a first attempt to address this question, let me describe the quality of that experience with the pen, and others like it. I am compelled, once more, to use the term “awakening.” In this experience, I awaken to the fact that this is, and that I am. I am here, now, in this body, in this world. I am in this miraculous and unrepeatable individual bodily being, in the presence of an object equally miraculous in its being, and in the presence of this unique relation of the two, a relation which is wonderful and fragile because it will be gone in a moment, never to return. It is. I am. I am awake. But this use of “I” is merely a convenience; a limitation of language. “I” am not doing anything, certainly not the “I” with which “I” normally identify. (N.B., what “I” identifies with that “I”?) The “I,” as “I” know it, has stepped out of the way to make this experience possible; it has fallen silent.

Even the language of “experience” suggests a subject-object relation that the “experience” has actually invalidated. What is there, then? There is openness, or a silence, in which being is allowed to manifest itself. Rather than speak about the aim of the Work as transmuting a “lesser self” into a “higher Self,” it might be preferable to jettison the language of subjectivity entirely. There is openness. Openness opens through the Work. The cramped little “I” or “self” (or “Self”) is a larval being. Openness emerges from this cocoon.

Why do the Work, then? For “love of being” is one answer that is sometimes given, or can be given. Another answer is “to be awake.” Sleep is unacceptable to me. Once I have learned that man is asleep, I cannot settle for being that sort of man. Readers will either identify with this imperative, or they will not. If they do not, then the Work is not for them. They may continue to slumber, if they so choose. In 1968, Robert de Ropp, a student of Ouspensky’s, published a simplified account of the Work under the title The Master Game: Beyond the Drug Experience. In it, he argued that human beings play a variety of “games” in life, and that he had chosen to play the game of “self-mastery,” and hence to do the Work. This approach to framing what the Work is about completely detaches it from Gurdjieff’s metaphysics, and (in spite of the great over-simplification in de Ropp’s book) I find it rather attractive.

Gurdjieff gives a cosmological answer to the question of why we should do the Work, detailing the role played by man in the universe, and by his awakening. I have said nothing about Gurdjieff’s complex cosmology in the foregoing. There are two reasons for this. First, it is genuinely complex and difficult, and under no circumstances could it be summarized in what is already an over-long essay. Second, the Gurdjieffian cosmology (which is essentially Gnostic in character) has always left me cold. Much of it seems arbitrary — meaning that Gurdjieff often gives us no reasons to accept the claims that he makes. We are free either to accept them or to reject them — and far from requiring faith or blind obedience from his followers, Gurdjieff enjoined them to question everything, and to “test everything.”

In that spirit, I will freely admit that I am unconvinced by these cosmological teachings, which are set out in some detail in Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous and in Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. Furthermore, I strongly suspect that much of this material (some of which is perennial, some of which is peculiar and idiosyncratic) was a kind of “myth” Gurdjieff offered up to his followers, to meet their need for a metaphysical framework for the Work, and, most especially, their need for a theodicy. The present essay therefore omits quite a lot.

Gurdjieff the man seldom evokes a neutral response. He is either adored as a saint or reviled as a fraud and conman. Like many figures in the history of Western esotericism, he seems to have been a combination of a genuinely realized being, in possession of real wisdom, and something of a mountebank. The latter impression partly has to do with the fact that he assumed different personae depending upon who he was dealing with, and to the fact that his own accounts of his life are so obviously part invention. Plus, his magnum opus, Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, can easily be mistaken for charlatanry of the highest (or lowest) order.

Nevertheless, Gurdjieff gathered around him a coterie of highly intelligent and talented individuals, who were certain that he had imparted to them a path to the achievement of a higher state of being. An initial acquaintance with Gurdjieff’s work, or with his followers, can result in dismissing both too quickly. This effect is, up to a point, calculated. If you find yourself intrigued by any of what has been discussed in this article, you should persevere. Even if what you encounter on entering into the Gurdjieffian movement seems initially bizarre or off-putting. Recognize that you may be tested in various ways. And recognize that your own responses may indicate that something in you feels threatened by what the Work brings.

As I have tried to make clear, the Gurdjieff Work is fundamentally conservative and anti-modern. It is an “anti-humanist” teaching if ever there was one. Gurdjieff rejects promethean modernism and wounds our vanity with his claim that we can “do” nothing, as well as his critique of Western man’s mechanicality. Further, there is a convergence here with the ideas of Heidegger, quite without either thinker being aware of the other. First of all, there is Gurdjieff’s insistence that man is not in control of his destiny. Like Heidegger, Gurdjieff holds that we are in the grip of societal (and cosmic) forces, while imagining all the while that we are masters of our fate.

For Gurdjieff, one can open to this situation through the Work, and achieve a kind of self-mastery even if one remains incapable of changing anything in the world. The decision to do the Work, to see, is free and can never become mechanical; it must be chosen every single time. But the decision to do the Work occurs only in and through releasement of the ego’s desire to do. This seems strikingly like Heidegger’s conception of Gelassenheit, “letting beings be.” Arguably, this is a “conservative” position because, as I have argued elsewhere, the “metaphysics of the Left [18]” consists of a denial of reality and an imposition on what is of fantasies about what ought to be, fantasies that deny to what is any intrinsic properties that resist human machination.

To reject this position has to involve, at a fundamental level, opening ourselves to what is — allowing it to present itself to us just as it is, without being filtered through pre-conceived, ideological notions. At the very least, we have to try to do this. We have to try to let beings be. The reader may be interested to hear that someone once wrote, “One of the striking things about the effect of Gurdjieff’s teaching on his pupils is that the men — at least those I have known — become more masculine and the women more feminine.” [9] [19] Why? Because through the openness taught by the Work, men and women become who they are.

If you are interested in Gurdjieff, where to begin? The worst place to begin is with Gurdjieff’s own writings. Gurdjieff planned a series of three books under the title All and Everything. The first of these is Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson. The modest purpose of this book is “To destroy, mercilessly and without any compromise whatever, in the mentation and feelings of the reader, the beliefs and views, by centuries rooted in him, about everything existing in the world.” He achieves this, in part, through such devices as incredibly long sentences, a narrative structure that is impossible to follow, digressions within digressions, the use of bizarre neologisms, and placing ordinary words in quotation marks so as to cause us to recognize their oddness and to question their meaning (a practice I have emulated in this article). Beelzebub is an incredibly difficult book, and most will give up in disgust after reading only a few pages. Those who persist will be rewarded, but only by devoting the most careful attention to the book. It helps that it is occasionally, and deliberately, laugh-out-loud funny (something I’m not sure all of Gurdjieff’s followers perceive).

The second part of All and Everything is Meetings with Remarkable Men, which I have already mentioned is Gurdjieff’s most readable book. It was made into a flawed but quite interesting film by director Peter Brook in 1979 (and recently released on Blu-ray in a new director’s cut). The third part of All and Everything, Life is Real Only Then, When “I Am” was never fully realized by Gurdjieff and survives only in fragmentary form.

The best place to begin to study the Work is where everyone else does: Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous. It is one of the most intellectually exciting books I have ever read and takes the form of an action-packed memoir of Ouspensky’s time with Gurdjieff and eventual break with him. A number of Gurdjieff’s followers wrote memoirs, and these make an ideal starting point. My two favorites are the de Hartmanns’ Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff, and C. S. Nott’s Teachings of Gurdjieff. This latter book, among other things, describes Gurdjieff’s only encounter with Aleister Crowley (short version: Gurdjieff thought Crowley was one seriously sick bastard). Ouspensky’s Psychology of Man’s Possible Evolution is quite short and worth a look. (His other Gurdjieffian books are only for advanced students — and take note that some of his books, such as Tertium Organum, were written before his acquaintance with Gurdjieff.)

Those who wish to proceed further should read Jeanne de Salzmann’s Reality of Being. De Salzmann was regarded by Gurdjieff as his chief pupil and was his designated heir. The Reality of Being is an edited compilation of her journal entries (translated from the original French). It is not for beginners, but I would say, without question, that it is the best book on the Work I know of, and repays careful, repeated reading.

With some serious reservations, I can also recommend two books by an author (a university professor) who writes under the penname “Red Hawk.” The first of these is Self Observation. The second is Self Remembering. These books really “give the game away”: they reveal much information that was once imparted only in groups. However, this information is mixed up with the author’s own idiosyncrasies, which include an annoying, squishy, liberal touchy-feeleyness (e.g., the subtitle of Self Remembering is “The Path to Non-Judgmental Love”). These books contain admirably clear explanations, but they must be read critically.

Of course, anyone who is actually in the Work will tell you that reading books is not enough, and that you cannot effectively Work on your own. A group is deemed indispensable. This is because others can help us to see ourselves in ways that we never can on our own. The types of self-deception we may fall into are literally infinite. It is the function of an effective “group leader” (and of a group) to bring us face-to-face with our ego and its lies. A part of us, a very strong part, resists being seen. It does not want what the Work brings. And it will find all sorts of ways to sabotage our attempts at awakening. These include deceiving ourselves into thinking that we are “doing the Work,” or making “progress” in the Work when really we are not. Gurdjieff was a master of administering “shocks” which brought individuals to greater self-awareness, if only for a moment.

Finding a “Gurdjieff group” is tricky. There are quite a few out there, usually in or near major cities. But they vary quite a bit in quality, as you might imagine. And there are con artists out there asking for large sums of money in exchange for “instruction.” Gurdjieff groups always charge money. Gurdjieff himself believed that people do not value something unless they are paying for it. A good rule of thumb is this: if you run across a group that is asking for more than $100 a month and won’t give students and other poor people a break, then turn and run. The groups that have the strongest claim to legitimacy are those affiliated with the Gurdjieff Foundations started by Jeanne de Saltzmann after the Master’s death (the headquarters of these are in Paris, London, New York, and Caracas). Proceed with caution.

Other Texts Mentioning Mr. Gurdjieff at Counter-Currents:

- Julius Evola, “Mr. Gurdjieff [20]“

- Anthony M. Ludovici, “Memories of Orage, Gurdjieff, & Ouspensky [21]“

- Christopher Pankhurst, “Giacinto Scelsi: A Soundtrack for Radical Traditionalism [22]“

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [23] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [24].

Don’t forget to sign up [25] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [26] Also, depending on who you ask, he was born on the 14th of January. Or the 31st of March, or the 29th of October.

[2] [27] A Presocratics Reader, ed. and trans. Patricia Curd and Richard D. McKirahan (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing, 1996), 43.

[3] [28] A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I.iv, section 6.

[4] [29] Nicolas Malebranche, Oeuvres completes, ed. G. Rodis-Lewis (Paris: J. Vrin, 1958-70), Vol. 2, p. 394.

[5] [30] Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, Meditation 6.

[6] [31] Curd, 41.

[7] [32] Curd, 59.

[8] [33] Gurdjieff himself did not use “the fourth way” as a term for his teaching; it was, however, widely used by Ouspensky.

[9] [34] C. S. Nott, Teachings of Gurdjieff (New York: Arkana, 1990), 98.