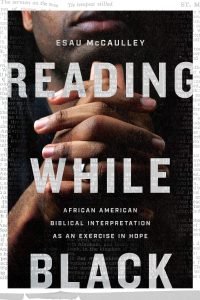

Esau McCaulley’s Reading While Black

Posted By Dabney Hixson On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledEsau McCaulley

Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope

Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 2020

Esau McCaulley has been on the faculty of Chicago-area evangelical bastion Wheaton College (alma mater of the likes of Billy Graham) since 2019, where he serves as an assistant professor of the New Testament. He is also a priest in the Anglican Church (despite his Primitive Baptist roots) and received his Ph.D. at St. Andrews in Scotland under internationally renowned New Testament scholar N.T. Wright. His dissertation, “Sharing in the Son’s Inheritance: Davidic Messianism and Paul’s Worldwide Interpretation of the Abrahamic Land Promise in Galatians [2],” is being published in 2021 in the respected Library of New Testament Studies series by T & T Clark. Not only is the title under review widely and vigorously promoted by respected evangelical publisher Intervarsity Press, but McCaulley has also been named the general editor of a forthcoming “multi-ethnic commentary series,” titled The New Testament in Color, from the same publisher. He has also been invited to write articles for national publications such as Christianity Today, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. His attractively designed personal website [3] includes a link to his professionally-produced “Disputer’s Podcast,” co-sponsored by Intervarsity Press and Christianity Today. And this is just the tip of the accolade iceberg for McCauley and his ever-increasing CV.

How, one might ask, in the cutthroat world of academia, does a freshly minted Ph.D. merit a plum teaching post, three simultaneous book contracts, and invitations to write for national journals and newspapers, while his faculty page [4] lists only one previously published academic journal article?

He who gets this kind of fast-track to success is either a one-in-a-billion genius or has made some Faustian deal with the devil. There is, however, another explanation. The clue comes in the title of his book Reading While Black. McCaulley is a new black “evangelical” intellectual being generously helped up the ladder of success while simultaneously condemning it.

Reading While Black is aimed at a popular audience, specifically for general black readers, but those of other races are welcomed to listen in on the conversation. Like other books of this type (like its more secular counterpart How to Be an Antiracist), it leans heavily on the author’s story. McCauley tells us what it was like to be a young black man listening to hip hop music, a genre that taught him how to “interpret the world that seemed to have its foot on the neck of Black and Brown bodies” in his city (p. 2). He found a ray of light in the Bible interpretation of the black church (what the author calls the “Black ecclesial interpretation”) (3).

In college, he studied African-American history and religion, finding that the reading in his Biblical studies classes mostly provided applications designed for “white middle-class Christians” (12). He was dismayed that there were so few “Black and Brown voices” (13).

Most of the black voices came from the “progressive” wing, while those blacks who promoted more traditional Christian views were “weaponized in evangelical spaces against Black progressive voices” (15). From Frederick Douglass, he learned the distinction between “slaveholder religion” and the Christianity “of Jesus and the Bible” (17).

The key to authentic hermeneutics, according to McCaulley, is to approach the Bible as “enslaved persons” did, to see the God of the Bible as “the liberator and humankind as one family under the rule of Christ” (19).

A “dialogue” between “the Black experience” and the Bible is what must be put forward in our day (20). By using this method, the author says he aims to be both progressive and traditional. He sees the book as a “love letter from a somewhat wayward son of the Black church” (24).

McCaulley’s orientation given, he then offers six chapters on the Bible and various topics.

The Bible and policing

This chapter begins with another “memoir moment” from the author. As a teen, he was pulled over at a gas station by the police, who were trying to crack down on the local drug trade. There were no arrests or harassment, but the brief stop and questioning by police became, of course, an example of racial oppression.

He then turns to Romans 13, a classic text for Christians on submission to civil authority, but suggests that the interpretation of this passage changes when the rulers are wicked. From there, he turns to a brief discussion of “policing” in the Roman Empire, drawing on Christopher J. Furhman’s Policing the Roman Empire: Soldiers, Administration, and Public Order (Oxford, 2012).

McCaulley concludes that contemporary African-Americans are uniquely situated to understand the experience of persecuted early Christians — the United States has crafted laws “over the course of centuries, not decades, that were designed to disenfranchise Black people” (38). What is needed is “a theology of policing” that protects black from unwarranted fear.

McCaulley expresses no appreciation for how equality under the law has essentially been secured in the modern era (if not routinely tilted in favor of minorities). There is no recognition of the fact that people of all races are generally arrested when they commit crimes, nor is there any discussion of widespread black criminality or the fact that blacks are generally hurt most not by police violence but by black-on-black crime, for which a strong police presence is usually welcomed by those of all races with any common sense. For McCaulley it is literally, and unironically, black and white. Police are oppressors. Blacks are innocent and meek victims. He has much to say about the “duties” of the police, but nothing to say about the duties of citizens to abide by the law. It is never mentioned that those who “fear” the police often do so not because they are innocent victims, but because they have done wrong and fear the repercussions.

The Bible and political witness

This chapter begins with a reference to Martin Luther King’s letter from a Birmingham jail, and the assertion that “Black Christians” have never had “the luxury” of separating “faith from political action” (48).

Just as a loophole was found to escape the weight of submission to authority in Romans 13, so here a loophole is found to avoid Paul’s admonition to pray for those in authority in 2 Timothy 2:1-4. Authorities need not be respected or prayed for if they “stand in the way” (52).

McCaulley sees Jesus calling Herod a worthless “fox” (Luke 12:32) as a prime example of political resistance. He sees another example in Paul’s reference to his present circumstances as the “present evil age” (Galatians 1:4), and another in John’s apocalyptic vision of the fall of Babylon (Revelations 18). Thus, “Protest is not unbiblical” (62).

The chapter ends with a review of Jesus’ Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5).

At one point, McCaulley notes that the teaching of Jesus “undergirds the actions of Paul, Isaiah, and Rev. Dr. King” (65). Really? King elevated in status to equality with Isaiah and Paul? That’s quite a promotion.

McCaulley asserts that if the church is going to be on the side of the “peacemakers,” there must be an “honest accounting of what this country has done and continues to do to Black and Brown people” (68). There follows a list of things that supposedly have to be “named” (whatever that means): “Housing discrimination has to be named. Unequal sentences and unfair policy has to be named. Sexism and commodification of the Black female body has to end” (69).

All the things that supposedly have to be “named” are generously blamed on the government. Who is responsible for sexualizing and commodifying the “Black female body?” FEMA, the US Postal Service, the IRS. Wouldn’t we say that the aforementioned hip-hop (and rap) music culture has had as much or more to do with this as anything else?

Biblical prophets addressed the sins of their own people. Nathan confronted David with “Thou art the man!” Jeremiah railed against his fellow Israelites (Where else did we get the term “jeremiad”?). Our new black prophets, however, seem to say nothing to their own people, instead pointing their fingers at whites or the government.

This is somehow considered “edgy” and “prophetic.”

[5]

[5]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [6]

The Bible and justice

The focus in this chapter begins with the Gospel of Luke. McCaulley claims the fact that Luke (a Gentile) wrote to a Gentile audience about the salvation of Gentiles has some special relevance for black Christians. He even calls Luke “a patron saint of African-American ecclesial interpretation” (79). He then tries to convince us that the “enslaved” would have felt special affinity with “Theophilus,” the recipient of Luke’s Gospel, since he supposedly first heard the Christian gospel by word of mouth and not by reading (78).

The line of fanciful interpretation continues when McCaulley next suggests that Zechariah and Elizabeth, the parents of John the Baptist, are equivalent to “the first generation of Black Christians who came to faith during slavery” (81).

This chapter also provides several examples of odd writing choices. At one point, McCaulley says that “the miracle of John’s birth spread like a virus of hope infecting the bloodstream of Israel” (83). A “virus of hope?” What’s next, the “constipation of joy?”

The author also makes some interesting remarks about the virgin birth, a doctrine that orthodox Christians (which he supposedly represents, as an evangelical) hold as essential to the faith. Still, the author tells us that some might find Luke’s stress on this venerable doctrine to smack of “sentimentalism or, even worse, fundamentalism” (85).

The “creative” interpretation continues with McCaulley’s analysis of Luke’s Mary, as he suggests a typological interpretation that I would guess is unique in the history of critical scholarship: “Mary stands in for Black (and all other) Christians who are called to give the entirety of themselves, their very bodies for a future that they cannot see . . . Mary is the patron saint of faithful activists who give their bodies as witnesses to God’s saving work” (86).

After some brief analysis of Jesus’ baptism and early ministry, McCaulley concludes that readers must get beyond “the slave master exegesis of the antebellum South” which bore false witness about God. Instead, one must affirm “our commitment to the refugee, the poor, and the disinherited” (91). In the conclusion, he takes a swipe at evangelicals who tend to care about the spirit but not the body, but then turns things around and makes sure also to take the same swipe at progressives who care about the body but neglect the spirit.

The Bible and black identity

This chapter begins with an effort to debunk the idea that Christianity is a white European religion. McCaulley argues that persons of African descent are in the Bible from the beginning and that Africans did not initially come to know the faith through colonization or slavery.

The Bible survey begins with the promise to Abraham that blessings will come to all nations through him (Genesis 12:3). It assumes that the sons of Joseph, Ephraim and Manasseh, were half-black because Joseph had an Egyptian wife. This assumption is problematic, however, since it is much more likely that the Egyptians of that day were, as they are now, primarily a Mediterranean people, rather than of black, sub-Saharan stock. The same objection can be lodged against the author’s claim that Simon of Cyrene (in Lybia), who carried the cross of Jesus, was also a black African (107-108). On the other hand, he is quite right to say that the Ethiopian Eunuch of Acts 8 was likely a sub-Saharan African.

Closing with reference to John’s vision in Revelation of all nations ultimately being part of the Christian movement and Paul’s oft-quoted statement in Galatians 3:28 that in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, McCaulley takes pains to point out this does not mean he accepts the claims of “colorblindness,” noting that “some White Christians have even begun to claim that they do not see color” (112). Why center on white Christians? Are they especially prone to accept this supposedly insensitive fallacy? McCaulley, in fact, makes the claim that race is forever, because God’s eschatology “requires my blackness and my neighbor’s Latina identity to endure forever,” though he does add that John’s final vision is incomplete “without Black and Brown persons worshipping alongside white persons” (116). No mention is made, however, of whiteness enduring forever. He closes: “Colorblindness is sub-biblical and falls short of the glory of God” (116).

The Bible and black anger

That such a chapter exists in this book is something of an acknowledgment that black rage exists. It also comes as little surprise, however, to learn he believes that whites are responsible for this because of their “dehumanizing” treatment of blacks.

This chapter begins with another memoir-esque narrative. This one involves McCaulley as a child. When sick at school, he called his mother’s workplace and was supposedly called a “N*****” by the person who answered the phone. He asks how this person even knew he was black: “Was it my diction or the register of my voice? Did my blackness seep through the phone and offend his sensibilities?” (119). This brought on a sense of rage. He continues: “I was helpless before this white man who didn’t know me” (119). McCaulley offers the previous statement with no seeming recognition of its latent hypocrisy. He assumes the person who answered his phone call was a “white man.” How did he know this? Was it his diction, the register of his voice, or something that seeped through the line? Is it possible the person on the other end of the line was a black man, and it was he who supposedly called McCaulley’s younger self the N-word?

McCaulley returns to the trope that black women are especially the victims of white dehumanization. They are “pushed and pulled into sexual stereotypes that present them as objects of pleasure. As hips and thighs develop so the threats to their safety” (120). Is he unaware of the statistics showing how rare it is for a black woman to suffer sexual assault at the hands of a white person? That, in fact, black girls and women are most likely to be assaulted by other blacks? While we are on the case, why not mention the role of Jews in producing pornography, dehumanizing men and women of all ethnicities?

While denouncing “colorblindness,” it appears that McCaulley is “black blind.” He never sees blacks as bearing any responsibility for their plight. He mentions here, of course, the rage induced by the legacy of slavery — “we were mercilessly dragged from our native land and flung to the far ends of the world to be beaten, bred, raped, and degraded” (121). Never, however, does he stop to ponder the fact that slavery existed before the colonial period and that it was Africans themselves who enslaved and sold their fellow Africans.

Once again, the author sees a special relationship between the Biblical people and enslaved people. Only they can grasp the significance of the exile of the ancient Israelites and the overflow of rage against the Babylonians as in Psalm 137.

In the end, he finds the answer to “the continual assault on Black bodies and souls” in the death and resurrection of Jesus, as suffering was redemptive and vindicated (135).

The Bible and slavery

The last chapter takes on the biggest topic: slavery. For McCaulley, this is the linchpin. If the Bible supports slavery, then it is immoral, and Christianity must be abandoned. Since the Gospels record no teaching of Jesus on slavery, he takes Jesus’s teaching on marriage and divorce as providing a proper hermeneutic. Jesus said that divorce has been allowed by God, but it was not his “creational intent” (141). The same is true for slavery.

The survey of the Bible’s teaching on slavery begins in the Old Testament. Since “God’s character speaks against slavery,” the positive Old Testament treatment of it must reflect divine permission and not approval. Even in these texts, there is a “trajectory . . . toward liberation” (151).

Turning to the New Testament, the focus rests on Paul’s epistle to Philemon. A supposedly important insight that black exegetes can offer is that Onesimus should not be considered a “runaway slave,” but one who had “escaped” (156). That, however, seems more than a little anachronistic. A bondservant on the lam in the first century is not equivalent to a runaway slave of the antebellum South. Furthermore, McCaulley suggests that if Paul had not demanded that Onesimus be freed from slavery by his Christian master Philemon, he should have. At the least, Paul was trying to “limit the damage done by slavery” and cause Christians to rethink the entire institution. One wonders, however, what McCaulley would make of R. L. Dabney’s articulate exegetical defense of slavery in his post-war book In Defense of Virginia and the South (1867).

There are many problems with McCaulley’s overly simplistic parallels between slavery as an institution in the Greco-Roman world and slavery in the antebellum Southern United States. Nothing is said about the role of white men (like Wilberforce) in bringing slavery to an end in the white Western world, while it continues in many places in contemporary Africa (like Sudan). Nor is anything said about the fact that America (and its historically white Christian population) fought a bloody civil war that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands and the eventual emancipation of slaves in this nation.

Bonus Track: On Black Ecclesial Interpretation

The six main topics covered, the book ends with a brief conclusion and an addendum, called a “Bonus Track,” tracing the history of Black scholarly interpretation of the Bible. Three main historical approaches to black reading of the Bible are suggested: acquiescence (internalizing “the negative understanding of Black worth found among white Christians”) (170); critique (using the Bible to argue against racism and slavery); and rebellion (“Nate Turner is paradigmatic for this strand of interpretation”) (171). On the contemporary scene, of these three, only critique and rebellion remain.

The most important recent development in African-American Biblical interpretation, according to the author, is the emergence of “womanist biblical interpretation,” a fusion of black liberation theology and feminism (180).

He closes by saying black evangelicals have to develop a “double apologetic” responding to “Black separatists and white progressives” (184).

Closing thoughts: This will never end!

Reading While Black, of course, plays on the mythical dangers and discrimination of “driving (or jogging!) while black.” White evangelical Protestant Christianity had long been rock-solid in support of the “religious Right.” But as Robert P. Jones demographically demonstrated with chart after chart in The End of White Christian America, those days are long over. Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016 was likely but a bump in the road on the way to the final destination of white Christian decline in this nation.

Woke culture broke the mainline white churches decades ago, and it is now overrunning evangelical churches and institutions. McCaulley’s book is but the latest specimen of this. He is not splitting any differences between progressives and evangelicals. He is a progressive and only a slightly more sophisticated and nuanced “race hustler” than those of the past generation.

McCaulley makes clear in the conclusion of the book that there will never be any meaningful answer to racism nor will racial reconciliation be achieved — literally till Jesus comes! The “long tradition of Black reflection on our pain will continue. The slave question will be with us to the eschaton” (167). This will never end! There is penance in this new religion, but no salvation.

One of the saddest things to see is that woke white evangelicals are so desperate to prove how much they are not racist that they are promoting scholars like McCaulley to professorships in top institutions, showering them with book deals, and propping them up with professionally-produced podcasts. If this book is any example, McCaulley just isn’t that sharp a thinker or writer. His prose is mediocre at best. There is little meaningful self-critique and plenty of hackneyed braying about damage done to “Black bodies.” If he did not have “black privilege,” he’d likely be just another religion Ph.D. on a glutted education market willing to take any kind of adjunct work that came his way.

No doubt, a good number of evangelical students will have this book assigned in their Biblical studies classes and be forced to endure reading at least some of it, and they will, of course, be told how important it is. Even N. T. Wright exudes in a cover blurb about his former student: “Esau McCaulley’s voice is one we urgently need to hear.” My guess, however, is that most readers of this book (and let’s face it, the mainstay of its readers will be whites, not “people of color”) will respond to it with boredom. It’s just not that interesting. You can’t prop someone up and declare him to be an intellectual (or even a “skintellectual”) with important things to say. His writing and thinking must compel this conclusion.

McCaulley’s does not.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [7] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [8].

Don’t forget to sign up [9] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.