Inheritors of the Earth: Port, Plain, & Mountain in Western Culture

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled9,130 words

As men and women of the Right, we are searchers for Truth. We believe that by finding Truth and living by Truth, we might know Beauty, and we might know ourselves. Essence is our mission and with it, survival. And so this essay will try to surface and then sketch three fundamental “lifeways,” or patterns that have shaped our race and over the course of thousands of years. Each are bound to place, geography, and space — a subject others have long philosophized about, including men like Carl Schmitt, who developed his thesis about the relationship between Land and Sea peoples, the Behemoth versus the Leviathan (Counter-Currents has published this Schmitt essay in full; refer to the notes for links). [1] [2] My aim is somewhat different, for it is not primarily focused on wars and geopolitics, per se, but on the organic life of a people and their society. The three lifeways that I illustrate in this article are those of Port, Plain, and Mountain.

This trinity has expressed itself in a variety of ways. The archetypal man in the Port City is a merchant, whose highest virtue is influence, purchased with wealth. The archetypal man living in the Plains is the yeoman, who esteems prosperity above all (which differs from wealth), and he achieves this through landed work ethic and thrift. And the archetypal man of the Mountain is the mountaineer, who values honor, which he keeps through jealous guardianship of his independence and acts of physical courage.

These three traditions may be tied to economies, or vestiges of past economies, respectively: mercantilism/capitalism, earlier feudalism, and the earliest tribalism of hunter-gatherers. Even their musical preferences have tended to differ in marked ways: mountain types enjoy more “rustic” instrumentals that echo plaintively in the hills: the bellows of the bagpipe, harmonica, and accordion, the piquancy of the banjo; those of the plains/flatlands seem to gravitate toward the haunting and clearer, but still slightly-twangy guitar and lilting fiddle; port cities have favored the piano and smoother, more seductive sounds from bass and trumpet. Men from the plains will make disciplined and dutiful soldiers. Men from the mountains will make fearless soldiers. And men from the port cities will endeavor to make money, come what may.

There are countries in the West that lack one archetype or other for the obvious reasons that some states do not have mountains, while a few do not border the sea. Nevertheless, most regions will recognize these three modes of being and how each has shaped their people’s character. Strong societies have been able to knit these groups together in webs of mutual respect and need, while those that could not have disintegrated.

This is meant to be part two in a series devoted to geography, archetypal lifeways, and the Western literary imagination surrounding the places European peoples have called “homeland,” but it is not necessary to have read part one [3] before continuing. While the first used Gothic-American literature, the second relies heavily, but not exclusively, on romantic/elegiac travel narratives and Romanticism proper — the close sibling of the Gothic movement, and one whose artists and authors were in love with Nature, nationalism, and what they called the “sublime.” [2] [4] Both are long essays, because they broach big subjects. Read at your leisure, and of course, additions in the comments are welcome — for the subjects are so big, that I’ve missed crucial parts of the story (and my sources are mostly in English). A primary goal pursued by the Dissident Right is to resurrect one of the oldest and greatest loves of our race: the love of the land. Native whites across the globe, whose ancestors carved a living space for you and all whom you love: dedicate your soul to the blood and soil that are one.

The Mountain

Hills draw like heaven,

And stronger sometimes, holding out their hands

To pull you from the vile flats up to them;

And though, perhaps, these strollers still strolled back,

As sheep do, simply that they knew the way,

They certainly felt bettered unawares

Emerging from the social smut of towns

To wipe their feet clean on the mountain turf. [3] [5]

Some time ago, I watched a documentary on K2, the peak second only to Everest in height and second to none in deadliness. The fellows who had reached the summit and come down again claimed to have “conquered” the mountain. It was like one of those ill-conceived moments when some mortal, drunk on hubris and the admiration of his friends, declared in the direction of the heavens that he could throw a spear further than Mars, or that when she looked into the glass, her radiance caused the beauty of Venus to pale in comparison. Men do not “conquer” a great mountain; they survive her, for she has merely suffered them to live. A slip on the ice, a momentary distraction, and they fall off the edge of the world or plunge down a crevice and headlong toward the world’s deep center. Starved lungs both gasp for more and shrink from the arctic air as every breath slices through their tender tissues. Hallucinations begin. The whitest of whites stab the eyes beneath ice-broken lashes. The quickest minds are reduced to thoughts that move like mid-winter molasses, and everything dissolves behind a narrowing gray-curtained vision. Each heavy step beats to a snow-siren song that bids climbers to sink down and to close their eyes and to give in to sleep. Should a storm or avalanche descend, no earthly power will save them from the night, nor the wind, nor the crush of entombment. The stone sides of great mountains are also the sites of gravestones. But if these ice-zombies with their blood-cracked mouths and blackened noses do manage to stagger back from their trip among the gods in their clouds, what have they conquered? Themselves, perhaps, and their human frailties.

But not the Mountain.

Perhaps no physical landscape has inspired more rapture and dread — or dreadfully rapturous poesy — than the Mountain, for the Mountain is sublime. [4] [7] It represents both freedom (escape from society, its norms, and its decadence) as well as sepulcher (snowfall may entrap travelers, avalanches may bury climbers, and coal mines may collapse atop tunnelers). In its majesty, the Mountain and its far turrets symbolize the gods and their thrones, for they are “The palaces of nature, whose vast walls / Have pinnacled in clouds their snowy scalps, / And throned eternity in icy halls / Of cold sublimity . . . / All that expands the spirit, yet appalls, / Gathers around these summits, as to show / How earth may pierce to heaven, yet leave vain man below.” [5] [8] It is “the shape of ancient fear,” of the kind that terrorized the village beneath Fantasia’s demonic peak. [6] [9]

Indeed, some mountains even have distinct personalities. They are retreats where men go to contemplate meaning and to seek answers by ascending the limits of their physical and mental heights. The Oracle at Delphi, located in the mountainous Phocis province of central Greece, remains a sacred site atop a rift valley that has hidden much of the ancient structure after successive earthquakes buried it below. Pindar’s verse, which eulogized Delphi’s “bronze walls,” explained how once there “Stood the pillars beneath, / [And] of gold were six Enchantresses / Who sang above the eagle. / But the sons of Cronus / Opened the earth with a thunderbolt / And hid the holiest of all things made.” [7] [10]

Mythical mountain dwellings have also included the celebrated halls of Valhalla, where a thousand generations of once and future warriors await the last event whose moment will bring them to an ultimate precipice of fate: glory and doom (for the two are married). The Mountain, then, is both beautiful with her blasted pines and her “many hues of heaven” — now “A gleaming flame in the dawn light,” then “a blaze of silver in mid-day. Gold and rose in the sunset and lilac and lavender in the dusk. Livid against the storm clouds and dark against the stars” — and awful in her cosmic indifference. [8] [11]

And to make a less romantic point: borders and state boundaries have at times been haphazardly drawn — determined through wars and their treaties, or the fall of empires and the fracturing of their territories into smaller, semi-homogeneous ethnic domains that change with the passing of dynasties and the movement of populations. But mountains were drawn by the hand of Nature (and always for a compelling reason), and so state authorities have used them to create “natural boundaries” in a way that legitimized what might otherwise have seemed arbitrary. In his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar argued that authorities who determined the lines that divided Rome’s European territories should endeavor to “adjust [them] to the topography of their substratum.” [9] [12] The Pyrenees and the forested highlands of Bohemia, for instance, have become lasting borders between peoples — and mountains have provided them with a source of national pride. What northern Italian does not cherish the Alps, or southern German his Black Forest hills?

Moreover, what sort of person or group chooses to make these forbidding monuments their homes? Granted, not every mountain or mountain range is as treacherous as the Alps, the Andes, the Rockies, or the Himalayas, but almost all of these regions remain sparsely populated. It is difficult to grow crops on rocky slopes, and travel is limited. Some of the most dangerous predators — wolf packs, tigers, bears, and pumas — prowl their grounds.

Their remoteness has thus bred a certain type of specimen: the stubborn, distrustful, and independent-minded mountaineer. In English, his other names have included: highlander, hillbilly, hilltopper, and cragsman. Communities of such men tended to belong to clannish (and often violence-prone) honor cultures in which their people valued physical courage as their primary virtue. They have viewed themselves, and others have viewed them likewise, as a folk cut off from the rest — literally and metaphorically above the rules of ordinary people. It is little wonder then that they retained belief in pagan rites and other forms of magic long after the disenchantment of the West.

[13]

[13]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Graduate School with Heidegger here [14]

Magic and Monsters in the Hills

Mountainous areas of Europe and America have been the scenes of some of the most bizarre episodes in Western history — episodes that have completely bewildered the city types and flatlanders sent to deal with them. In the mid-eighteenth century, French rustics from the Margeride Mountains of the (now-defunct) province of Gévaudan suffered a series of vicious attacks thought by natives to be the work of a supernatural beast. Lone shepherdesses and peasants were found partly eaten and their throats ripped out. I have written elsewhere that belief in both the supernatural and the scientific was not antithetical, but often reinforced one another. The eighteenth century was the apogee of scientific naturalism, and it was a common assumption among naturalists that undiscovered creatures (who may have been capable of metamorphosis) existed. The superstition of the peasants and the enthusiasm of learned men eager to catalog this new man-eating species caused descriptions of the Beast to grow more fantastic by the day. As the killings continued to multiply in the bluffs, so did the sense of panic across southwestern France. The various bounty hunters sent by Louis XV to stop the monster expected the cooperation of Gévaudan residents, but at nearly every turn, their efforts to find the Beast were complicated by a lack of local assistance. The Gévaudan people were too used to being left alone in their hills and were therefore reluctant to take orders from outsiders — even if it meant sabotaging their would-be rescuers. [10] [15]

Several centuries before the case of the Gévaudan Beast, the Pyrénées to the west were the setting of the dramatic witch-craze among the Basque people (a large percentage of the accused and confessants were children). Inquisitors hailing from the Spanish court traveled north to the Catalan-Navarrese mountains in order to quell the hysteria. The event was so outlandish that it all but ended the Spanish witch hunts and Inquisition. Scores of “suspects” confessed, then recanted, then confessed again, next admitted that they’d been coerced into pleading “guilty,” until they finally quit providing intelligible answers at all. Frazzled authorities threw up their hands and concluded that the locals had, for some inscrutable reason, succumbed to collective insanity — but not to witchcraft. Weird things happen in the thinner air, it seems. [11] [16]

The Scottish Highlanders

In terms of area, roughly half of Scotland is considered “the Highlands,” and it features many different ranges, including the Grampian and Northwest peaks. While not all Scots are Highlanders (the Highlands is one of the most sparsely populated places in Europe), most Scots have shared a certain attitude toward southerners and begrudged any interference from them, resulting in a reputation for cussedness. Romantic poet Geroge Gordon, Lord Byron, who spent his childhood in Scotland, went through periods of anti-Scots feeling, an opinion not improved when he learned that a Scottish nobleman had stolen several friezes from the ruins of the Athenian Parthenon. In an imagined dialogue between an Englishman and Minerva during which the goddess accused him of defacing her temple, the Englishman pleaded,

Daughter of Jove! in Britain’s injured name,

A true-born Briton may the deed disclaim.

Frown not on England; England owns him not:

Athena, no! thy plunderer was a Scot . . .

And well I know within that bastard land

Hath Wisdom’s goddess never held command;

A barren soil, where Nature’s germs, confined

To stern sterility, can stint the mind . . .

Each genial influence nurtured to resist;

A land of meanness, sophistry, and mist.

Each breeze from foggy mount and marshy plain

Dilutes with drivel every drizzly brain . . .

Foul as their soil, and frigid as their snows

. . . schemes of petulance and pride

Despatch her scheming children far and wide . . .

In quest of lawless gain they issue forth.

And thus – accursed be the day and year!

She sent a Pict to play the felon here . . . [12] [17]

The poem is the bitterest anti-Scots diatribe I have ever read.

But Byron’s contempt for the English won out in the end. Like many fellow-Romantics, whether drawn to nationalism or to the charisma of a peerless warlord, he cheered the latest attempt to renew the Dream of Rome by force of Napoleon’s Grande Armée. To Byron, Waterloo was a disappointment. But he did reserve praise for the conduct of the Scottish troops during the battle. In his paean to their bravery, the poet described how “the war note of Lochiel [sounded]. . . / Savage and shrill! / But with the breath which fills / Their mountain-pipe, so fill the mountaineers / With the fierce native daring which instils / The stirring memory of a thousand years . . .” [13] [18] In a moment of supreme panache, the cavalry unit of the Scots Greys charged French lines, and while passing through the 92nd Gordon infantry and bellowing to the sound of bagpipes the cry of “Scotland forever!” so stirred were their fellow-countrymen on foot, that they grabbed the stirrups of the riders and were thus propelled to the front.

[19]

[19]Stanley Berkeley, Gordons and Greys to the Front, 1898: The legendary charge of the Scotsmen at Waterloo.

The Appalachian Moonshiners

The most well-known mountain people living in North America were those who are descended from the Scots and have made their homes in Appalachia. And like their kin across the sea, they were born storytellers who have resisted outside interference and encroachment onto their territory. Laws were more likely to be dismissed than followed (or even considered), for Appalachian communities had their own codes of conduct. A good number of them resented the Confederacy when its officials insisted on “earth and water,” just as they despised the Union when its soldiers demanded the same price. Still, the region also supplied both the Confederacy and the United States throughout its history with some of its fiercest warriors. Yet perhaps the most archetypal figure of this colorful people was that of the Moonshiner. In the 1870s, Harper’s Weekly commissioned a nineteenth-century equivalent of “what’s the matter with Kansas?” when its editors sent an investigative reporter to peer into the alien world of the Appalachian Moonshiner for the entertainment of their urban readers.

Because of federal surveillance, the distiller plied his trade by the light of the moon, the better to avoid detection, hence the appellation “moonshine.” Though moonshiners risked arrest, jail, and heavy fines, they were not in the illegal whiskey business for the money (unlike more modern and nastier drug dealers and their cartel suppliers). Moonshine manufacture, in fact, “enriched no one, and especially not those who [made] it,” for “[they] who distill[ed] illicit whiskey [were] of the poorest . . . classes” among those inhabiting “the mountainous section of the ‘dark and bloody ground’” of Kentucky. [14] [20] The shacks used for the purpose were often “so dreary and desolate that wild-cats and other beasts of the forest” were constant dangers. Amidst “the mountains, in ravines, briers, brushes, trees thick and tall, in caves and under cliffs . . . these . . . law-breakers eke[d] out an existence as romantic as it [was] remarkable, [raising] their own grain, erect[ing] their own still-houses and attachments, and . . . [they] confine[d] the labor of making liquor for their own families . . .” Though cocky in their native hollers, when the mountain men were taken into the city to face distribution charges, they seemed meek and wholly intimidated. Indeed, “very few of them [could] read and write, and many [had] never beheld aught else of the world than [existed] within a hundred miles of their own habitations.” [15] [21]

The rest of the piece detailed a series of whiskey “stings” carried out by the US Marshals Service and on which the writer accompanied them. True to the abilities of most journalists who have ever written for a large New York publication, he managed to make caricatures of all involved, his story filled with pistol-waving bullies and ignorant bumpkins of the deepest dye. These men of the hills simply “[did] not consider the making of whiskey by illicit means a crime,” for the same reason that they did not consider themselves as belonging to the same breed as those habitants of the coast and plain. [16] [23] On the rooftop of the world, “Here place and people seem to be / A world apart, alone, — / Cut off from men by spate and scree.” In this, at least, the article’s author did not exaggerate. [17] [24]

The Port City

She looks a sea Cybele, fresh from ocean,

Rising with her tiara of proud towers

At airy distance, with majestic motion,

A ruler of the waters and their powers.

And such she was; her daughters had their dowers

From spoils of nations, and the exhaustless East

Poured in her lap all gems in sparkling showers.

In purple was she robed, and of her feast

Monarchs partook, and deemed their dignity increased. [18] [25]

Byron’s poetic narrator here seemed to praise Venice for its beauty and power — its “majestic” purple robes that were the envy of all the kings of Christendom and beyond. Only read closer, and the words become criticism. Venice was the product of glorified pirates — the “spoil[ers] of nations,” who valued above everything wealth and “gems” to “[en]dower” their daughters. This “ruler of the waters” seemed to rise above and to outdo Nature, yet the narrator could only describe the city’s triumph in the language of the natural world, for “she look[ed] a sea Cybele, fresh from the ocean,” and her “majestic motion” moved in time to the ceaseless tides that will one day swallow all her “proud towers.” Venice was less a victory snatched by man from Nature than she was an extension of it — of the waves that surrounded her, sluiced through her canal-lanes, and defined her. To put it another way, listen to a “merchant of Venice” when he advised a visitor: “Venetians never tell the truth. We mean precisely the opposite of what we say.” This was the Venice that took part in the sack of Constantinople in 1204 (one of the most important centers of Christianity) during the Fourth Crusade; but it was also largely responsible for winning a magnificent victory against Islamic forces at the 1571 Battle of Lepanto. Look at how the “Sunlight on the canal is reflected up through a window onto the ceiling, then from the ceiling onto a vase. And from the vase onto a glass, or a silver bowl. Which is the real sunlight? Which is the real reflection?” Of course, the deeper question the merchant-guide meant to ask was, “what is true?” Like the waters that defined the city, Venice and Venetians were fluid, changeable, intuitive to the moment’s need and able to adapt to the “rhythm of the lagoon.” [19] [26]

Like plains and mountains, ports have had a dual nature in Western history and literature: they were the glamorous places where the bright young things flocked — so much to do there, so much trouble to cause. With the advent of street lighting in the early modern era, busy ports even managed to banish the limitations imposed by darkness (an underappreciated revolution). The night still places limits on rural plains, smaller towns, and mountainsides, but the urban conquest of the night has resulted in cities “that never sleep.” This fundamental change in the early modern West — street lighting — may be at the heart of cities’ scorn of any and all limits, for just as they trumpet multiculturalism, they indulge multi-appetites as well. Every whim must be catered to, every demand met, at any hour of the day. And so, port cities have also been breeding grounds of sordidness: the spread of crime, the accumulation of refuse, and industrial-level corruption. If the Mountain represents Nature at her rawest sublimity, and the Plain the middle path — man’s “improvement” of the land and his harnessing of Nature with farms, gardens, and husbandry, even as he plays the supplicant there to her cycles and seasons — then the City represents man’s most comprehensive attempt at overcoming Nature and forming his own edifice of power to rival the proud Mountain (though it must be noted that man’s Port must always use Nature’s bounty of the sea to its advantage).

The city’s duality was also reflected in myth. It has signified beauty, wealth, and civilization. Long ago Atlantis was a city-state of demigods — a tall, graceful race that produced a fabulous society. Asgard, home of Odin, the All-father and the Norse deities, governed all nine realms of creation from its magnificent seat. But cities have also symbolized vainglory, sin, and the ephemerality of existence (after all, they are, by definition, artificial). Mythical cities were thus the targets of wrath and usually suffered a catastrophic fall. Atlantis and its treasures sunk beneath the waves. The Ragnarok of prophecy demolished Asgard. Sodom and Gomorrah incurred divine punishment for want of virtuous men. The Tower of Babel crumbled (an early example of globalism gone awry — God was a nationalist, readers). A lesser-known Breton folktale described the fate of Ys — a city whose high walls kept the sea from deluging it whole. Only the king had access to the key that could unlock the floodgates, and he kept it on his person, always. In a plot mirroring that of Pandora’s Box, the king’s daughter stole the key from her father’s neck while he lay sleeping. Determined to let her lover into the city, she then unlocked the dam. Within moments, the entire kingdom was drowned. [20] [27] In short, cities have always provoked a comeuppance.

[28]

[28]Évariste Vital Luminais, Gradlon’s Flight, 1884: The King of Ys escapes the sea while his daughter does not.

Yes, real and imagined, they seem fated to succumb to the fury of the four elements: fires have laid waste to London and Pompeii; according to ancient (including Biblical) sources, waters once flooded much of the civilized world; winds from hurricanes wiped coastal cities off the map; the earth’s tremors have devastated Tortuga and Lisbon. And, of course, man has proven just as capable of destroying his cities as well. Good night, old Dresden and Baltimore, the one burnt by sudden holocaust and the other by a thousand little fires.

“Suers” and Misery in the Metropolis

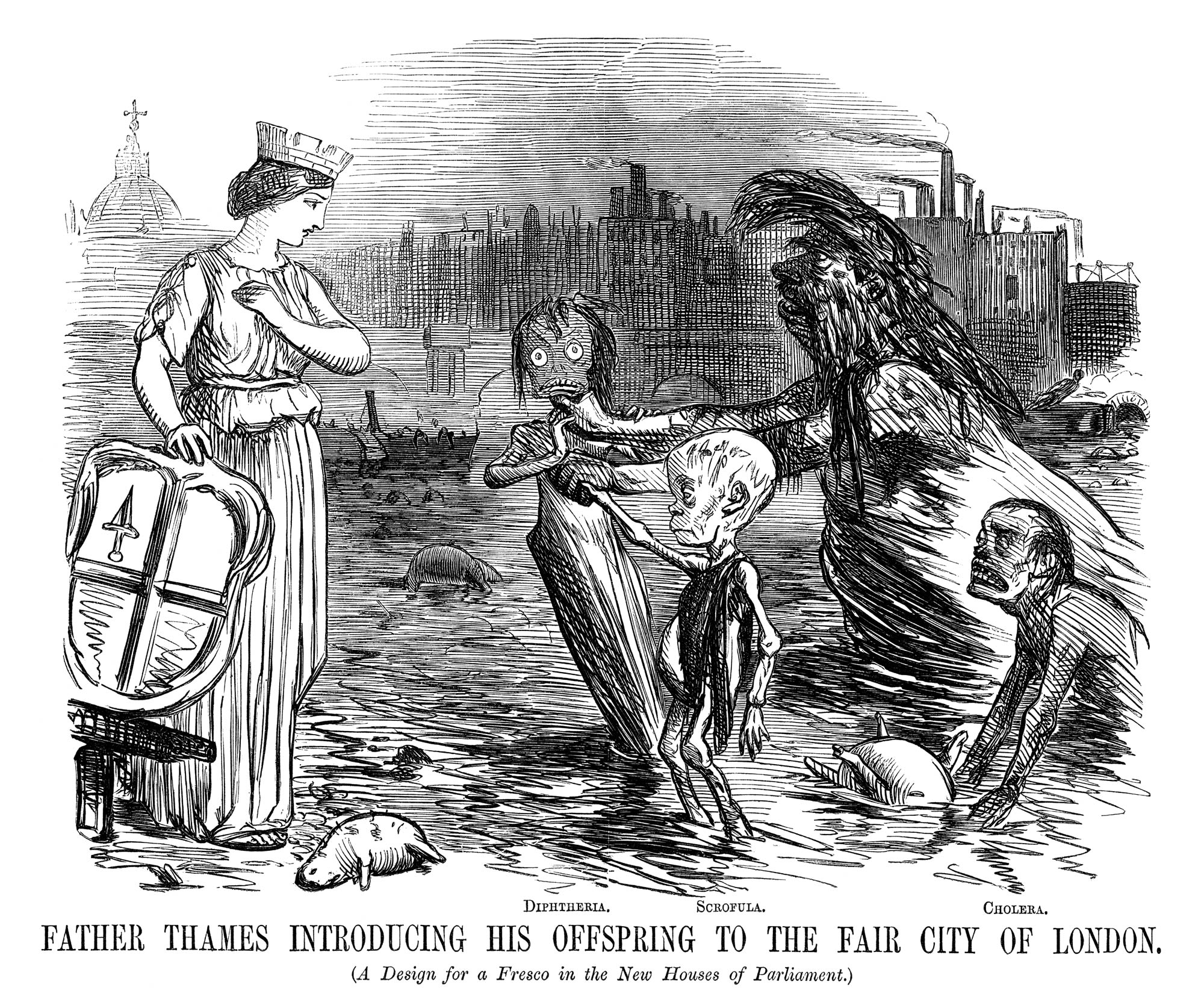

Indeed, large port cities have been a mixed blessing for Europeans and their descendants. They have tended to be filthy places that, for most of their histories, lacked adequate drainage systems or access to clean water. In the mid-nineteenth century, for example, the Thames of London had amassed so much waste that its waters had essentially become concentrated sewage sludge and easily the most contaminated river on earth. The 1840s London Times received a letter from an aggrieved worker in the slums, who complained: “We live in muck and filth. We aint got no privez, no dust bins, no water splies and no drain or suer in the whole place. If the Colera comes, Lord help us.” [21] [29] In fact, “the Colera” did come that year, and thousands of Londoners died in the outbreak, most near water supplies that were polluted by cesspools. It had never been uncommon for pedestrians to hold handkerchiefs liberally spritzed with perfume up to their noses when passing close to the river’s foul vapors, but July and August of 1858 were different. In what must have been one of the worst summers in the city’s history, the odor from the Thames, exacerbated by the oppressive heat that cooked to a stew centuries’ worth of human, animal, and industrial effluvia, sent London residents to their sickbeds and brought businesses to a stand-still. Parliament could barely function. Londoners forever after referred to it as “The Great Stink.”

[30]

[30]“Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London,” Punch, July 3, 1858. With a different caption, this cartoon could double as an anti-migrant poster.

Only recently have cities become places of well-balanced diets and nutrition; a century or so ago, those living in the countryside were more likely to have enjoyed fresh water and a healthful variety of foodstuffs, while urban dwellers aplenty suffered from rickets and pellagra (not to mention bouts of typhoid and any number of diseases enabled by crowded conditions and poor hygiene). Plagues and pestilence usually emerged first among the wharves of places like Bristol, Trieste, Venice, Marseille, and Amsterdam then proceeded to ravage the regions beyond.

Cosmopolitan Miami, the “Capital of Latin America”

And now to consider two case studies: Miami’s sobriquet above should make readers pause (or cringe), not to ponder the truth of its claim, for who can seriously argue against it? But to absorb that truth. Fully. The British American colonies that coalesced into the Union were formed from people who saw their settlements, largely, as being in direct opposition to the (Catholic) Spanish and Portuguese domains to the south. The informed reader may chime in: “but the Florida territory was, for a long time, a Spanish possession, only ceded to Anglo-Americans in the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty.” Just so. But like most Latin American territories north of Old Mexico (or New Spain, as it was once called), Florida was sparsely populated — meant to be a buffer between British settlements in the north and the Spanish Caribbean. The most notable inhabitants living in Florida at that time were escaped slaves and Indians who formed swampland “maroon” communities. I have no interest in badmouthing the European Spanish/Portuguese people. Who among the Western explorers can compete with the legendary conquistadores? When schoolchildren in the past learned about the men who conquered the Americas, the most exciting figures were from Iberia; they were the Catholic knights who felled entire empires in Central and South America. To illustrate the character of such men: one spring during college, I took a Texas history course taught by a delightfully old-school professor. As an introduction to the subject, he brought a beautiful (and ancient) Spanish leather-bound volume to class, then passed it around for our eager (but careful) perusal. The cover was still supple, and the pages remained, for the most part, intact. After we’d all gotten a chance to marvel over this gorgeous piece of history, the professor said in passing, “yes, actually, the leather is from the skinned hide of a Moor.” These were hardcore people.

That said, their mostly mixed progeny in Latin America has suffered endemic problems and created dysfunctional societies (some countries like Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, etc. have fared much better than others). So, to admit that large and important port cities in the United States, like Miami, have become “Latin American” — no, the “Capital of Latin America” — means that the United States has become Latin American, too, and that bodes ill for the fate of the nation. Not so long ago, Miami was a sleepy port town on the southeastern tip of Florida. But after the Second World War, it became a city bloated with aliens and nomads, almost overnight. Huge numbers of Cuban “refugees” fled the Cold War Castro regime and settled there, and they, in turn, were followed by Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and all manner of Latin flotsam and Haitian jetsam that washed up onto the beaches. The cocaine era “enriched” the city, and drug dealer millionaires invested in construction and high rises — turning the quaint seaside resort into a dirty nouveau-riche playground. By the 2000s in “all of Miami-Dade County, all of Greater Miami, and very much including Miami Beach,” WASPs were “members of [a] shrinking and endangered little tribe . . . a dying genus.” It may now be the only city in the world where “over half its residents [are] recent immigrants.” [22] [31] Miami has imported Latin America, while at the same time it has hemorrhaged white America. It’s a world city now — peopled by oligarchs, cartels, favelas, and Jewish retirement communities — and only loosely claimed by the United States.

[32]

[32]You can buy Greg Johnson’s Here’s the Thing here. [33]

Thessaloniki (Salonica), the “Mother of Israel”

Let us now turn east toward the Balkans. The Greek city of Thessaloniki has been a major port on the Aegean for thousands of years, and like many other Mediterranean sites, it has belonged to a succession of empires: it was part of Alexander’s Macedonian kingdom; a “free” city-state of imperial Rome; a trading hub ruled by Rome’s Byzantine successor; a possession of the Ottoman sultans; and a retaken port, finally, by the Greeks as the largest city in its Macedonian province. Yet the historiography of Thessaloniki (at least in English) has been completely dominated by Jewish scholars, who have claimed it as the “cradle of European Judaism,” or even as the “Mother of Israel.” [23] [34] According to these historians, benign Ottoman rule allowed the city’s huge Jewish community to thrive in a sort of “golden age” mythology, ended when Turkish and Greek nationalists — and then Axis powers during the Second World War — destroyed the multicultural dream that was Salonica. Indeed, Thessaloniki had few Jews before the fifteenth century, but a massive influx of Spanish exiles fleeing the Reconquista established a major presence in the then-Ottoman port, which grew until ethnic Greeks and Muslims were each outnumbered by the Jewish population. The cosmopolitan and trade-centric character of this southeastern European port attracted them (multicultural areas always do). The result bore a notable resemblance to the Miami of the future.

Just as Miami is culturally and racially the “capital of Latin America,” even as it belongs to the United States, Thessaloniki from the 1600s to the early 1900s was the “capital of the Jewish Diaspora,” even as it belonged to the Turks, even as it was an ancient Greek city in the shadow of Mount Olympus. Of course, it suffered from the problems that have always attended that peculiar group. Most “commercial transactions and capital in Macedonia were either in Jewish hands, or controlled by [the] Jews . . . and through them European capital gained control of the credit system throughout the hinterland . . . Most of the time, banks granted credit to [businessmen] only after they had been recommended and guaranteed by [Jewish] agents.” [24] [35] At the same time that these wealthy (mostly Sephardic-Italian) families were lords of the region’s capitalist economy, radical working-class and intellectual Jews formed the “The Socialist Workers’ Federation of Salonica.” This situation might have seemed contradictory, but Jewish capitalism and socialism in Salonica were two faces of the same strategy: both meant to keep ownership of the city and control of the southern Balkans’ political economy by undermining the nineteenth and twentieth-century nationalist fervor then sweeping the region.

Thessaloniki today is a different place. After several catastrophic fires, World Wars, and population exchanges, Jews and their power have diminished. Now that it is in European hands once again, may the port of Thessaloniki remain ever after, more Greek and less eclectic.

The examples above make it clear that the city, and in particular, the port city, is oriented outward — beyond and away across the water toward adventures and trading opportunities — while the attitudes of mountain and plain are focused regionally, or locally — rooted to earth and soil. The competition of a busy place dominated by merchants and sea power has led to imperialism, cosmopolitanism, and an unquenchable thirst for more. Is this drive for what some call “progress” wholly bad? Lest we forget, many glorious past civilizations were often based around port cities. The genius of Golden Age Greece emerged from city-states by the sea. Would the ideas and works of men such as Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Herodotus, Hippocrates, and Thucydides have emerged without the gathering-place of debate and great minds that the environment of Athens nourished within its forums? We owe our fundamental principles of logic, ethics, rhetoric, and meaning to this short time in Western history. But lest we also forget, this same era was ended by Athenians’ own ambition. The prosperous port city has nearly always become an overmighty port city, and then finally, an imperial city. Greece never recovered from the Peloponnesian War(s) (431-404 BC), the duels fought between the Athenian empire (the Delian League) and the Spartan alliance (the Peloponnesian League). Cities are man-made, and they are thus essentially based on the denial of natural limits — and even of human limits.

The Plain

More bleak to view the hills at length recede,

And, less luxuriant, smoother vales extend;

Immense horizon−bounded plains succeed!

Far as the eye discerns, withouten end,

Spain’s realms appear whereon her shepherds tend

Flocks, whose rich fleece right well the trader knows . . . [25] [36]

The third and final geographic lifeway is that of the Plain — the most tragic of the three. Like mountainous regions, “plains” can be narrowly or capaciously defined; for the purposes of this essay, they are the more or less flat lands that may or may not be partly forested or marshy, but are pastoral in nature and agrarian. Plains may be bountiful, or barren; fruitful of wheat, or of sorrow; reaping what the gentle breezes of August and September sowed, or reaping the whirlwind of the kind of Fate that has felled kingdoms; quaint verdant gardens, or terrible desolation. Fields of poppies bloom where one hundred years ago No-Man’s-Land yielded nothing from its bloody sludge but a harvest of razor wire, bayonets, and bone. The Plain is the dominion of Demeter and Mars — you think them so different? They are not, for both deal in sacrifice. Here were the old rites of cyclical life and death observed (and in many places, still are).

Mythic examples have included the paradise of Arcadia, or the happy rest that awaits the virtuous dead in the fields of Elysium. But Dante’s Second Circle of Hell (reserved for the lustful), within which guilty souls are forever buffeted and tossed about by winds across a sterile wasteland also comes to mind. Readers of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings may recall the “Dead Marshes,” “bare and bleak” in the Dagorland Plain and beyond the distant menace of Sauron, the Deceiver’s, realm. According to Tolkien’s mythology, long ago, elves, men, and orcs, “They fought on the plain for days and months at the Black Gates. But the Marshes have grown since then, swallowed up the graves; always creeping, creeping,’’ and candles lit their corpses. [26] [37] They lay “in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water . . . grim faces and evil, and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead. A fell light [was] in them.’” [27] [38] Faint whispers of black speech haunted the fen, while the lurid glow of ghostlight pierced the mists. Lord Byron also captured this somber quality during the poet’s Grecian travels, a country he claimed was “no lightsome land of social mirth . . . When wandering slow by Delphi’s sacred side, Or gazing o’er the plains where Greek and Persian died. Let [us] approach this consecrated land, And pass in peace along the magic waste.” [28] [39] Can land be both sacred and a “waste?” Of course it can.

Unlike those in the mountains, who have often been content to ignore the goings-on in the capitals, or in the booming ports, plains people cannot usually afford to overlook the machinations of the cities, to which they must ship their produce; and for their part, authorities in the city find the recalcitrance of the plains — their vulnerable, resource-rich breadbasket and taxable base — an open challenge that they cannot abide. Most English speakers when asked about the French Revolution will think of A Tale of Two Cities — Paris and the executions of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and other aristocrats by way of Madame la guillotine. But the French Jacobin movement of the 1790s had an even uglier side. The historical Vendée region of France, a bucolic province south of the Loire River Valley, was a partly coastal plain that bordered the sea, but it had no major ports during the eighteenth century, and it was (and remains today) mostly agrarian. The peasants of the Vendée revolted against the Republic established by the Revolutionaries in Paris, largely due to the strongly-felt Royalism and Catholicism in that part of the countryside. In one of the most pitiless campaigns in French history, Republican forces waged a war of extermination against the Vendéen people, making it an especial point to kill civilian women, so that as few Vendéen children as possible would be born in the aftermath to later take up arms and avenge their dead fathers. Some estimates of the casualties resulting from this civil war number more than 240,000 dead (an incredible number for that era). From 1793-1796, the Vendée was less an expanse of wheat and cattle-grazing grassland and more of a killing field.

Of Balkan Plains and Ancient Battlegrounds

The region of southeastern Europe is another example of the tragic character, the entwined nature of a plains-people’s blood and bone mingling with their native soil. British author Rebecca West wrote a long book (my copy runs to nearly 1,200 pages) about her wanderings through Yugoslavia and the Balkans during the interwar and Second World War years. She was not a “woman of the Right,” and she opposed fascism, the nationalists of Spain’s civil war, as well as the Bolsheviks of Russia (her fervent anti-Communism would alienate most of her Leftist friends in later life). But she was a person who thought with her own mind and formed her own opinions — which she rarely feared to share. And among some of her tedious ruminations on the rise of the militant Right in Europe that emerged to oppose the march of the Red Bear were the most gorgeous descriptions of an area most Americans know next to nothing about. And one of her more striking illustrations was of “Old Serbia” and the plains of Kossovo (which was how she chose to spell it).

During a drive into the country, an aging peasant guide named Constantine pointed to a white church among the thistles, “This is our church that we Serbs built for Kossovo . . . [and] from there we will see the plain where the Turks defeated us and enslaved us. Where after five-hundred years of slavery we showed that we are not slaves.” The party began to walk in the tall grass toward the structure, til their steps brought them higher and afforded them the sight of the “great plain.” There “the dead Turks lay. To [Constantine] the dead Christians were in heaven, or were ghosts, but not under the ground, not scattered lifeless bones; only the Turks perished thus utterly.” A “stillness” enshrouded them. Its appearance and spiritual resonance was not like the plains of “the vega of Granada or the English fens, that are flat as a floor,” but Kosovo’s “land [lay] loosely, like a sleeper, in a cradle of featureless hills . . . Kosovo more than any other site . . . arous[ed] that desolation. It spread peacefully into its vast, gentle distances, slow winds polishing it like a cloth passing over a mirror, turning the heads of the standing grain to the light. It [was] a look of innocence which [was] the extreme of guilt. For it [was] crowded with the dead.” [29] [41] Kossovo’s golden wheat and battle ghosts perfectly captured the nature of the plain-lands and its tillers of the soil — haunted by the dead whose bodies the earth reclaimed. Due to its heavily-borne responsibility of manning the “gateway of Europe,” with wide tracts of open space that encouraged hordes of armies from the “exhaustless” East to invade the comparatively small (and fertile) peninsula of Europe, the Balkans and Ukraine were familiar with Fortune’s Wheel and the tragedy of history. A parochial awareness of this past has defined the Plain in a manner unlike the high indifference of the Mountain, or the petty indifference of the Port.

Of White Tenant Farmers in the Lays of Alabama

America, of course, has also enjoyed a strong tradition of agrarianism and yeomanry — those for whom the earth was their profession, grief, and passion. If asked for an example of such farmers, most Americans would point to the Great Plains or the Midwest — that interior area of flat country that Francisco Coronado explored in the 1540s while on an epic quest for Cíbola (the sighting of the vast plains of present-day Kansas finally convinced him that nothing of worth existed beyond them). But the gently rolling lands of north-central Mississippi and Alabama also belong to this heritage. The Antebellum Deep South was home to a large number of white yeoman and subsistence farmers, but the War and Reconstruction impoverished an already poorer area of the country and fundamentally changed the nature of work and race in the South. Places that bore the scars of battle became parceled pieces of property on which tenant hands and sharecroppers farmed for rent; yeomanry weakened as grinding debt-slavery buried an increasing number of poor whites under its burden. In a classic work of poetic prose (interspersed with poetry-proper), James Agee, a traveler cum philosopher like Rebecca West, and belonging to that same ilk of brooding, interwar romantics, illustrated the lives and landscapes of Depression-era tenant farmers. [30] [43] Its narrative form was almost a song akin to those composed by ancient Greek tragedians, and not to everyone’s taste.

Agee described a “pastoral night” when lonely houses stood “against the pines” and “bristling cloud . . . the soft field raised, in the soft stare of the cotton . . . All spreaded in high quietude on the hill.” [31] [44] These houses in “the vast Southern country morning sunlight . . . all left open and defenseless . . . [shone] quietly forth such grandeur, such sorrowful holiness . . . that this square home as it [stood] in unshadowed earth between the winding years of heaven [was] . . . one among the serene and final, uncapturable beauties of existence: this beauty [was] made between hurt but invincible nature and the plainest cruelties and needs of human existence.” [32] [45] Here was the essence of the Plain and the men who have lived there: a melancholy determination among them absent in either Mountain or City — a fatalist’s view married to a resolve unafraid to face a struggle that would only end in death, season by season, year after year. The quiet hero of the Plain, and unless one has lived this kind of rhythm, difficult to understand. They “have no memorial . . . [but] perished as though they had never been . . . and their children after them. But these were merciful men, whose righteousness hath not been forgotten. With their seed shall continually remain a good inheritance, and their children are within the covenant . . . their seed shall remain for ever . . . their bodies are buried in peace, but their name liveth for evermore.” [33] [46] A fitting eulogy for the ancient laborer of the earth: that man unnoticed and necessary.

[47]

[47]You can buy Greg Johnson’s White Identity Politics here. [48]

Conclusion

Scholars have discussed the history of the modern West (1450-present) as an age of centralization; nation-states coalescing, languages standardizing, and laws codifying, etc. But there was a persistent pattern that emerged, a division that remained deep, or in some cases, deepened further still. Men of the Mountain were a breed apart, no matter the efforts of kings and lawmakers to integrate and thus to control them. Merchants of the Port became increasingly divorced from their nations of origin and thought of themselves as “men of the world,” or some altogether different people. Residents of the Plain suffered the worst of every economic or military crisis, while business in the cities and custom in the hills continued. There have been exceptions: industrialization shifted life in much of Appalachia when coal mining companies employed those folk to blow the tops off of their mountains, to spend much of their lives underground, choking on toxic dust — when before they had reveled in their heights and breathed freer and cleaner air than any other group. But this has not made them less alien-seeming to people on the coasts.

A healthy society or nation is able to balance the interests and lifeways of Port, Plain, and Mountain, for each has its contribution to make. It is able to encourage the wealth-creation and innovation of port cities while curbing their tendencies toward monopolistic greed and disloyalty; to glean the benefits that a stable farming community provides — rootedness and industriousness — while checking over-exploitation of the land and the stagnancy there that resists change for the better; to admire and sometimes to harness the independence of the mountaineer, while taming the excesses of his wildness, his lawlessness. Many Western countries today have failed at this and have ceded almost all the power to their cities, thus reaping the consequences of globalization and enabling the development of despotic and parasitic city-states, whose people never gaze inward toward Plain and Mountain, except to sneer. Worse still, they are less and less answerable to the people who comprise the true nation, who must suffer so that the city-states and the elites who manage them may prosper. In today’s globalized metropolis we find the worst examples of our civilizational decay: nonwhites swelling in their ghettos; the core-rot of government and finance, whose administrators scheme the demise of you and of me; the place where the professional class that is now all but synonymous with chirping HR progressivism (the epicurean without taste and the “revolutionary” without resistance become one banal clot) curdle together — these bureaucrats comprise the new First and Second Estates of the West, our “educated” clerisy; so much traffic and trash.

Vile spots. Cysts rather than cities.

While they have unquestionably aided the rise of great societies, just as agriculture has, cities have also been originators of civilizational disaster — an affliction that has most cursed the ports. It has been so easy for masters of enormous wealth and power to gaze from their “proud towers” across the sea and wonder: “whom and what else can I master?” In their fantasies, they have imagined themselves as masters of the entire earth. Such a mindset in such a place as the metropolis — built to defy limits and the natural world — may be all but unavoidable. But the age of megacities is a very new phase in human history, and who is to say that it will continue to dominate white societies? The city in its current form is, in the long run, untenable (particularly in multiracial cities). Given their current trajectory, they might become almost wholly Third World slums for the colored underclass, and where few decent folk will want to live or work. A new version of the “company town” in rural areas might be resurrected (not necessarily a good thing); something that we might call neo-feudalism may emerge in the countryside. As unwieldy conglomerates like the United States begin to lose power, groups could soon purchase land with the understanding that the federal agreement no longer will apply to them, and thus carve out tax-free and US-free zones. Perhaps this is a desperate hope that Monrovia, Liberia will not be, to quote some forgotten source, “what the end of the world looks like.”

It is a sobering thought, but Western/white nationalists will have to destroy a significant number of their nations (or what’s left of them) in order to resurrect them again. Many of us have a healthy Romanticist strain that stirs our blood with thoughts of a European renaissance, a rebirth of nationalism, and the celebration of the glorious feats to which we are the heirs. Romanticism of the cities once gave Westerners the confidence to make their national dreams realities; provided a gathering place for philosophers and artists and soldiers of the movement to rally. Romantics of the rural plains and country contributed a sense of tragedy and tradition that countered those of the city with grounding and circumspection (can seasonal/cyclical people be other than tragedians?). And mountain Romantics? They have always known not to look for salvation in the gadgets of man, but to Nature. “There,” says the Highlander as he points to the far pavilions of rock and cloud, I will “lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.” [34] [49]

NB: I began writing this piece well before the events of Wednesday, January 6. The spectrum of emotion among dissidents caused by the “storming” of the Capitol and its aftermath has struck me most of all. Some have relished images of politicians trembling with fear; others have felt “queasy” at the prospect of a coming crackdown; more than a few have sounded the death knell for the old party system with grim satisfaction. Before full-blown civil wars and revolutions, time seems to quicken; the list of “outrages” or momentous incidents occur one right after the other and before the full significance of any can be determined. The present seems too packed for these times not to involve some fundamental shift. It is foolish to think that the activities of national populists will be unopposed — especially as they gain strength and confidence and a willingness to act. The backlash that occurred was predictable, and we should steel ourselves for more to come. For now, that is the price. Myself, I feel no joy. Wars are opportunities, but they are uncertain things, always.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [50] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [51].

Don’t forget to sign up [52] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [53] Counter-Currents has the full translated text of Carl Schmitt’s Land and Sea, and it is broken up into nine posts: Part 1 [54], Part 2 [55], Part 3 [56], Part 4 [57], Part 5 [58], Part 6 [59], Part 7 [60], Part 8 [61], Part 9 [62]). Schmitt’s interest in this dichotomy emerged from the intense rivalry between Britain (a sea power) and Germany (a land power).

[2] [63] The Romantic movement in the West, beginning in the mid-eighteenth century and ending in the Victorian era, was an artistic reaction against Neoclassicism and various Enlightenment strains that valued reason and rationality; in contrast, Romanticists stressed nature, emotion and authenticity, used the Middle Ages as inspiration, while combining elements of beauty and horror. Its adherents favored the rise of nationalism across Europe. Notable Romanticists included: the quoted George Gordon, Lord Byron; Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, Frederick Turner, Francisco Goya, and Eugѐne Delacroix.

[3] [64] Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh (Chicago: Academy Chicago Printers, 1979). The poem was first published in 1864.

[4] [65] The definition and geographic imperatives of a “mountain” are not clear. It has no altitude threshold, and people have very often referred to hills as “mountains.” For the purposes of this essay, I posit only that a “mountain” is “elevated and looms high in the imagination.” See Judith Matloof, No Friends but the Mountains: Dispatches from the World’s Violent Highlands (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 4.

[5] [66] George Gordon, Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (Black Mask Online, 2000), 58-59.

[6] [67] This is a reference to Walt Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia, easily the most creative movie the studio ever produced and my personal favorite. The last two musical pieces are especially powerful: a Satan-figure who terrorizes a town from atop a menacing peak in Night on Bald Mountain is followed by Ave Maria.

[7] [68] Pindar, Pythians, 7.8-9.

[8] [69] M. M. Kaye, The Far Pavilions (New York: St. Martin’s, 1997), 73.

[9] [70] Bernard Debarbieux and Gilles Rudaz The Mountain: A Political History from the Enlightenment to the Present, Jane Marie Todd, trans. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 45.

[10] [71] See J. M. Smith’s Monsters of the Gévaudan: The Making of a Beast (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[11] [72] See Lu Ann Homza’s Religious Authority in the Spanish Renaissance (Baltimore: John’s Hopkins University, 2000).

[12] [73] George Gordon, Lord Byron, “The Curse of Minerva” in Peter Cochran’s “Byron’s Poems about Scotland,” 5.

[13] [74] Ibid., 8.

[14] [75] “The Moonshine Man,” Harper’s Weekly, (October 20, 1877), 822.

[15] [76] Ibid., 821.

[16] [77] Ibid., 822.

[17] [78] Henrik Ibsen, “Mountain Life,” (Famous Poets and Poems.com).

[18] [79] Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, 66.

[19] [80] John Berendt, City of Fallen Angels (New York: Penguin, 2005), 1-2.

[20] [81] See Lewis Spence’s Legends and Romances of Brittany (Global Grey Books, 2019), 137-138.

[21] [82] “Letter to the Editors,” The London Times (July 9, 1848).

[22] [83] Tom Wolfe, Back to Blood (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2012), 5.

[23] [84] See, for example: Mark Mazower’s Salonica: City of Ghosts (New York: Harper’s, 2005).

[24] [85] H. Şükrü Ilıcak, “Jewish Socialism in Ottoman Salonica,” in Southeast European and Black Sea Studies (2, no. 3, 2002), 119.

[25] [86] Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimage, 11-12.

[26] [87] J. R. R. Tolkien, The Two Towers (London: HarperCollins, 2012), 820.

[27] [88] Ibid., 823.

[28] [89] Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimage, 44.

[29] [90] Rebecca West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey through Yugoslavia (New York: Penguin, 1994), 837-838.

[30] [91] Tenant farmers were distinguished from sharecroppers, for unlike the latter, tenants who rented parcels of land from landlords/planters used their own animals and equipment and thus kept larger portions of the crop. Blacks tended to be sharecroppers.

[31] [92] James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2001), 68-69.

[32] [93] Ibid., 117.

[33] [94] Ibid., 393.

[34] [95] Psalm 121: 1-2, KJV.