The Plymouth 400 Symposium Yankee Wisdom, Yankee Work: Henry Cabot Lodge & Frederick Winslow Taylor

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,226 words

On December 18, 1620, the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Bay, on the western part of Cape Cod Bay. They were a small group of people, a mix of Protestant religious fanatics [2] and venture capitalists. They would go on to found an enormously successful society.

They were followed by a slightly different group — the Puritans. The Puritan leaders sailed to New England on the Arbella [3]. The Pilgrims wished to separate from the Church of England, the Puritans wished to purify the Church of England of Catholic influences. The Pilgrims and the Puritans were theologically similar, but in England, the Puritans’ insistence on being part of the Church of England complicated matters and helped bring about the English Civil War. If one grew up in a Christian household of any denomination in the United States, you carried out your religious duties within a framework influenced in some way by New England’s Puritans.

The Yankees — I don’t know why they are called Yankees — are the descendants of the English Puritans. They mostly originated in East Anglia and eastern England with a secondary origin location in the West Country excluding Cornwall. From their base in the Plymouth Colony in Connecticut and the Massachusetts Bay Colony they were able to demographically expand. They would go on to move West and become the dominant culture in upstate New York, Michigan, and the other parts of the northern United States. The manners and accents of Iowa are exactly like that of Oregon — it is the vehicles, clothes, and tattoos that are different. Both states are populated by Yankees.

The way Americans phrase things often has roots in Puritan literature. Steven Baskerville writes:

For all its insistence on a plain style therefore, Puritan literature has seldom failed to move by its very absence of sophistication. Emerging at a time when the English language itself was undergoing an enormous expansion, Puritan discourse has had an impact on our social and political vocabulary comparable to that of the Elizabethan poets and dramatists on literary style, and it has done so by popularizing and expanding upon the poetry and drama of perhaps the most influential written work in the English language, the King James Version of the Bible. [1] [4]

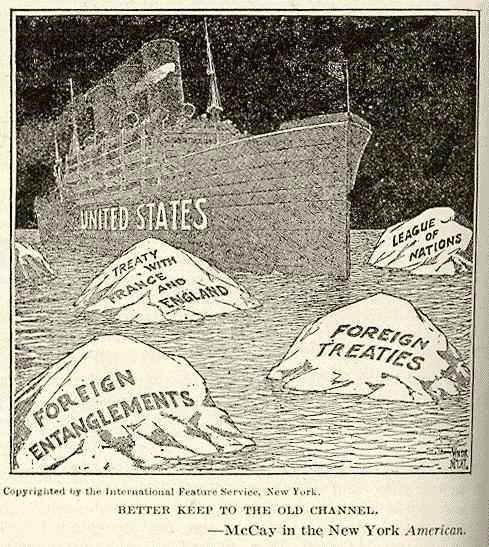

There has never been a time when Yankees didn’t have an enormous influence on the United States, but a high point was most certainly during and just after World War I. One of the issues of the day following that conflict was how America should engage in the world. It was two Yankees that framed the debate [5]. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Sr. (1850-1924) argued that the United States should not enter the League of Nations. Abbott Lawrence Lowell (1856-1943), the President of Harvard, argued in favor of entry. The ideas raised in the debate continue to be applicable today.

[6]

[6]In 1919, the United States rationally discussed involvement in world affairs. The debate was between two Yankees and moderated by a third Yankee — Calvin Coolidge of Vermont.

The Wisdom of Henry Cabot Lodge: America First vs. Isolationism

Recently, I watched a pompous windbag newsman discussing the “Senile Joe” Biden election “victory.” One of the things he was happy about was that he thought it was a great idea that Americans were leaving the “isolationism” of President Trump’s administration. President Trump wasn’t really an isolationist, but he did reduce American involvement in morally dubious operations in Syria and encourage wealthy nations like Germany and South Korea to pay more for their own defense. Donald Trump’s policy was a long time in coming.

Americans have always been empire-building and involved in overseas operations. As early in American history as 1690, soldiers from Massachusetts attempted to conquer Quebec [7]. Even the arch-isolationist Thomas Jefferson sent a large, heavily armed expedition to North Africa. The devil in foreign relations is in the details.

[8]

[8]Then and now, a policy of American intervention in the affairs of far-off nations carries enormous risks.

Henry Cabot Lodge’s opposition to the alliance system that would create the League of Nations was due to several problems that still apply in a basic sense today. I’ve updated the basics of Lodge’s ideas and put things into my own words:

- Alliance systems create contacts, and contacts encourage wars. (i.e. the alliance systems in Europe that turned a double murder into a global war in 1914.)

- Interventionism causes the US to become involved in conflicts in obscure places, like Somalia or the Balkans, where there are no real American interests.

- Foreign entanglements can create immigrant waves, such as the Somali scourge in the US today.

- Interventionist ideas have a logic that leads to the United States protecting any nation against “aggression.” This vague, semi-immoral principle tends to be unevenly applied (Israel attacks whomever, whenever). Additionally, the “good guys” as portrayed by the media, like Kurds, are often just murderous savages.

It is important to note that an America First foreign policy and isolationism are two separate things. It could very well be in America’s best interest to support a proxy somewhere as well as to deploy troops far forward and in harm’s way. Isolationism can allow rival nations to create a hostile system of alliances against the United States also.

It’s all quite difficult to know what exactly the goldilocks zone of isolationism and America First self-interest is, but without a shadow of a doubt, the US has a large network of allies, many of whom are engaged in a conflict with powerful enemies, and many of these allies hate each other — such as the Greek-Turkish rivalry. The British destroyed their empire by intervening in Germany’s border dispute with Poland in 1939. Had the British stayed neutral, there would not have been a World War II, or a Holocaust, or an Iron Curtain. Alliance systems appear to work — until they don’t.

A Problematic International “Contact” Americans Need to Know About

America’s political and military support for different nations doesn’t automatically create peace as I’ve heard interventionists contend. In recent years, the US government provided a great deal of weaponry to Azerbaijan. Later, there was something of a weapons sales ban, but American-developed weapons and technology sent to Turkey and Israel got passed to Azerbaijan anyway [9]. Americans must give a wink and a nod to this situation since Azerbaijan is supporting America’s continuing efforts in Afghanistan [10], although Osama bin Laden is dead and the pathology-ridden Afghani people can be managed with a simple travel ban.

Some of the weaponry includes unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). This year, Azerbaijan waged and won a war of aggression against Armenia using those weapons. Azerbaijan’s use of UAVs — even those supplied to them by American allies and not directly by America — should be seen as quite alarming from an America First perspective. It shows why “contacts” lead to wider wars as Henry Cabot Lodge Sr. warned.

To explain, UAV “swarms” and UAVs capable of fast, high-altitude flight with precision bombing requires considerable technical knowhow, a robust command and control element, and an integrated network that is secure from cyber and electronic attack. All of this is developed by American technicians and everyone knows it. Americans will get the blame for what will follow from this situation.

Some clear problems that will follow America’s direct and indirect support to Azerbaijan are:

- the potential ethnic cleansing of Armenians in the captured portions of Nagorno-Karabakh,

- a vengeful Russia that can damage US interests elsewhere in their own right,

- and the temptation for China and Russia to work together against American interests in the Indo-Pacific.

It is also not unreasonable to suppose that some young Azerbaijani buck will turn to jihad and cause Americans problems in the future. Saudi Arabians, officially subjects of a critical US “ally,” are a longstanding Islamic menace. The vicious god of Islam has a long history of repossessing the blood of its secular half-followers and turning them into a killing machine.

I’d also like to add that in places where there is a sort-of-peace, such as Korea, Americans are giving away their industry while supporting their supposed ally.

I’d argue for the following principles to guide America’s foreign policy.

- Upholding American interests is the highest ideal in foreign policy. If it is in America’s interest for isolationism, so be it. If not, so be it. Exactly what this entails needs to be a constant national conversation.

- The only nations the US should be in a permanent relationship with are the so-called “Five Eyes [11]” of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

- The United States should also seek to keep the trade relationship between England and the Low Countries functioning.

- The further east American involvement in Europe goes, the greater the risks and smaller the rewards. There are no vital American interests east of the Vistula River.

- America should support Latin American development and stability while keeping down immigration.

- America should not ally with an unstable, corrupt, and reckless nation that is involved in a conflict with a powerful neighbor.

- Americans should not support a proxy war on behalf of an ally. This is immoral. Instead, proxy wars should only directly aid American interests. America should also not serve as a proxy for any other nation.

- American policy can be amoral, but not immoral.

Smart Work: The Ideas of Frederick Winslow Taylor

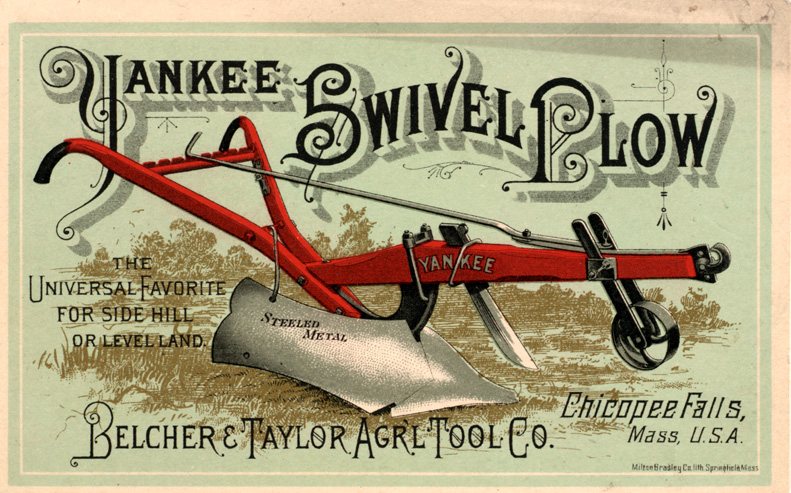

The Yankee settlers of New England immediately started to get involved in agriculture and textile manufacturing when they arrived in 1620. It was not long before they had their own merchant fleet that they used for trade and complex commercial activities. The Yankees sought to use their time wisely. They wished to “improve the time.” It was a criminal offense to be idle in New England.

The other Yankees — those of Pennsylvania whose regional origins were in the Northern Midlands of England (Lancashire, Cheshire, etc.) and were Quakers also took work seriously. The Quaker idea of work was called “cumber and calling.” That is to say, work should be done for the greater glory of Divine Providence, not just for earning a living. The Quakers also had a concept called “redeeming the time.” They carefully kept track of time and wished to use it well, but not hastily. They built things to last.

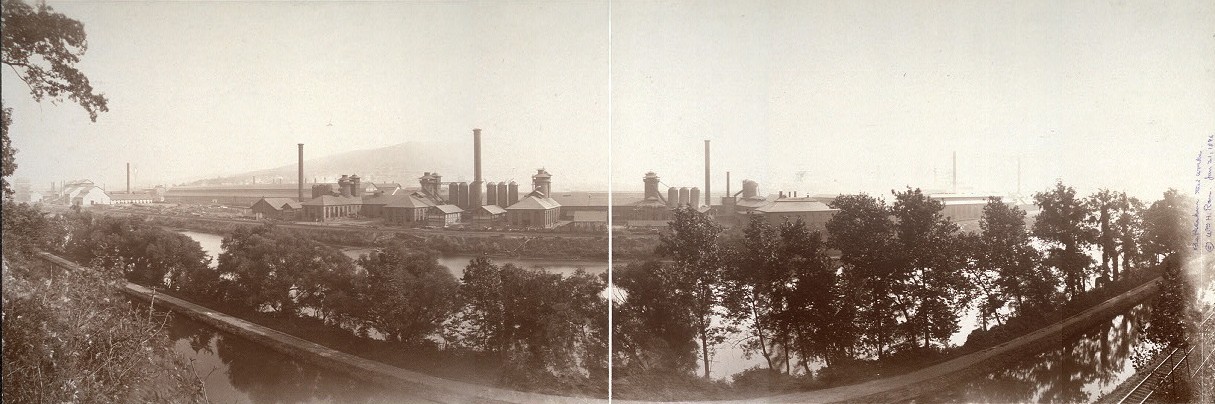

A Yankee/Quaker whose roots went back to the Mayflower that should be discussed is Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915). Instead of becoming a lawyer like his father, he worked as a machinist and quickly rose in Pennsylvania’s industrial economy. He developed the concept of scientific management.

Taylor argued that an increase in the production of goods led to bigger profits for the firm, higher wages for the workers, and more happiness for society in that there would be more goods — like shoes — that make life nicer.

Taylor believed that all industrial processes could be examined and made more efficient. This included traditional trades. He studied the motion of bricklayers to make them more productive and examined how much energy a laborer expended on ordinary tasks. He took into account advice from old shop hands and new college students. He determined the best way to cut metal and created a side industry to best carry out that process. His book on the matter is The Principles of Scientific Management (1911). It is a quick, easy read and filled with practical advice that anyone in any leadership role can use.

Taylor developed new ways to make old processes more efficient in four steps.

- Develop a science for each element of a man’s work to replace the old rule-of-thumb method.

- Scientifically select and then train, teach, and develop the workman.

- Heartily cooperate with the laborers to ensure all the work is being done under the principles of the science that has been developed.

- Admit that there is an equal division of the work and responsibility between management and workmen. Managerial tasks can’t be dumped on the workers.

Taylor was quick to offer incentives, including pay schedules that maximized income, productivity, and profit. He also argued that workers should be sifted for intellectual aptitude. He flatly states that firing people is a responsibility of leadership. His goal in any process improvement was to increase wages by 60 percent.

The language Taylor uses in The Principles of Scientific Management is simple and moral. It is something that the Puritans would have understood. Taylor is sympathetic to the common working man and sought to better his efforts.

America’s Puritan (and Quaker) values have been beaten down to embers by our hostile ruling class. They seem to think crudeness, such as that in Borat: Subsequent Moviefilm [14] is equal to a cumber and calling that seeks to carefully preserve America’s extraordinary national power as well as do good work every day.

Our Puritan heritage is but embers; it is now our job to make those embers flames again.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [15] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [16].

Don’t forget to sign up [17] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [18] Steven Baskerville, Not Peace But a Sword: The Political Theology of the English Revolution (Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications), 2018, p. 412.