No Country for Old Ghosts: A Literary Tour of Gothic America

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAs an American, I find European theories about this country and its character intriguing (or amusing) — particularly those formed from intimate experience. Of course, such theories presuppose that there is and has been such a thing as “the American people,” or “ethny” from which to draw an assessment. I submit two, not quite antithetical, but competing European judgments about the United States. The first, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in an 1827 poem, serenaded “We, the Rubes of the United States of:

America, you’re better off than / Our continent, the old / You have no castles which are fallen / No basalt to behold. / You’re not disturbed within your inmost being / Right up till today’s daily life / By useless remembering / And unrewarding strife. / Use well the present and good luck to you / And when your children begin writing poetry / Let them guard well in all they do / Against knight- robber- and ghost-story. [1] [2]

This has long been one of the prevailing opinions of the greater white world — America was the pollyanna of the West (at least it was until recently). We have been the torch-bearers of confidence, dreams, optimism, self-invention, Manifest Destiny, and whiggishness. Not to mention, progress, progress, Walt Disney, and more progress. We’ve demanded happy endings and loathed reality. Goethe insulted America with praise. Though not burdened or “disturbed” with memories, we lacked culture, history, and that certain je ne sais quoi that imparted to the European an elegant world-weariness. In other words, we weren’t suffering, because we weren’t interesting.

But there was an alternate view. British author D. H. Lawrence had less patronizing (but harsher) words:

. . . in America Democracy was always something anti-life. The greatest democrats . . . had always a sacrificial, self-murdering note in their voices. American Democracy was a form of self-murder, always. Or of murdering somebody else . . . The love, the democracy, the floundering into lust, is a sort of by-play. The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted. [2] [3]

Of these descriptions, which is closer to the truth? Indeed, it may surprise those of Goethe’s mind to know that America is/was one of the darkest places in the civilized world. And it certainly has had its “disturbed” memories. In this country, there was always an intensity, an evangelical fervor about its people — something I’ve called the “John Brown Eyes.” I believe Lawrence’s quote referred to that indelible legacy left by the frontier on the American psyche — the hardened and violent men needed to conquer it; mothers who could stand to bury their children by the side of the dusty and desolate track west, knowing they would never return to their graves.

By way of the great American essay and novel, let’s shiver as we explore four primary regions that have, in turn, formed two pairs of sectional foils — North and South, the Middle West and California — that have illustrated the American Dread of Lawrence, rather than the American Dream of Goethe. The catastrophe of the War of Secession made foils of New England and the South. For those who believe they understand the “Civil War” and the old and only semi-buried hatchet between northern and southern counterparts, I have another analogy. The War was a bar fight begun by two drunks named Massachusetts and South Carolina (the most troublesome states in the nineteenth-century Union), and whose bigger, stronger friends then felt obliged to join the brawl the hotheads had instigated. An exaggeration, perhaps, but one truer than most of the poppycock spouted about the subject these days. Likewise, the catastrophe of the Great Depression made foils of the heartland and the West Coast, as midwesterners fled the poverty of the Great Lakes and the dust of the Great Plains. Since then, Ohio has curled its lip at permissive California, and for its part, California has pretended that it never thinks of dreary Ohio at all.

Northern and Southern Gothic literature were possessed by fears of rot, the South in an earthy and the North in a transcendental way. Both North and South indulged in a taste for the supernatural. The South was haunted and inherited its haunts from Civil War days. Most of the savage killing during that conflict took place on Southern and border state territory. Lurid elements of voodoo from the South’s associations with African slaves lent a unique ghastliness to its horror genre. Puritan New Englanders were also adamant believers in the paranormal. They had faith in God, but they sometimes had more faith that the Devil and his minions were out to get them. Authors of these regions indulged in overwrought passages, but southerners often did so in a luxurious, almost feminine manner, while northerners took a more pompous tone.

Nightmares in Middle America and LA, on the other hand, revolved around those adrift, yet settled and those belonging, yet restless. Macabre tales of the Middle West and California, by contrast, were not so absorbed with witchcraft and the demonic. A large part of the reason for this must have been that, unlike New England and much of the South, neither the middle of the country nor the far West had large and unbroken tracts of dark forests (excepting parts of the Ohio Valley and the Pacific Northwest) that have always denoted enchantment, surrealism, and mystery to the European imagination. Where could monsters have hidden in a wheatfield? The vast Midwest was full of plains and plain-speaking people (and if the unreal was mentioned, it was more often a science-fictional/UFO potboiler). In LA, the city itself was the flesh-grinding beast that devoured its children. Writers of the heartland seemed to adopt a journalist’s pose — their tone that of observers (though not disinterested ones) piecing their notes together, as if to distance themselves from the stories that affected them so intimately. California’s authors favored the minimalist approach. Whether they imagined that this pared style made their writing “authentic” or not, it often sounded like a script: short lines for maximum impact and with the bluntness of a screenplay.

What follows is a discussion of regional “knight-robber-and ghost stories,” some of which were true, but all of which were “True.” They have defined, in four flavors of gothic narrative, America as Europe’s darker child.

[4]

[4]You can buy Greg Johnson’s White Identity Politics here. [5]

Southern Gothic

No region has pulled off “twisted” like the South. It has suffered from acute history and one separate from the rest of the continent: for centuries the South was a slave society, and it boasted a more rigid class system of landed aristocrats, as well as yeomen, mountain people, and backwoodsmen; its perpetual wrestling with the “Black Question” has made Southerners more likely to be racialists; its states were slow to industrialize; and it fought and lost the most wrenching war in the history of the Republic. Because of this essential difference, the South manifested a certain inability or refusal of “straightness.” It was much too humid for justice to run its true course, for things to grow up and unhindered toward the sun, instead of curling down and slinking around the shadows where worms and grubs squirmed in the dirt. Its pine forests and swampland gave rise to “Walls of thick vegetation [that] rose up on all sides and arched overhead in a lacy canopy that filtered the light to a soft shade.” In a thunderstorm’s wake, the air left behind was hot and steamy. Beneath the sprawling kudzu and Spanish moss, one felt “enclosed in a semi-tropical terrarium, sealed off from the world that suddenly seemed a thousand miles away.” [3] [6]

Peninsular Virginia, for instance, was both the loveliest and the creepiest place in which I have ever lived. The colonial town elders still hadn’t come to appreciate the benefits of street lighting by the year 2017, and drives after dusk were adventures. I often felt like I was one wrong turn away from disappearing, maybe forever, onto a winding road toward Powhatan’s revenge; in the rearview mirror, the tall, dark woods devoured all trace and track of my existence. The word “atmospheric” has lately become an over-used modifier in book and film reviews, so instead I’ll describe Virginia as heavy. Heavy with the freight of dead generations, with the weight of their glory and calamity. In some ways, I was glad to leave Old Dominion behind.

Loozy-anna was similar in nature, but less genteel about it. I remember a stretch of parish road along which no guardrails separated drivers from the swamp on either side. Every few miles I caught sight of the bobbing hood of some unlucky vehicle as it lost its battle against the bog waters. Road signs alternated from quoting Scripture to advertising an “ADULT VIDEO SUPERSTORE!” (which, disappointingly, looked to be little more than a rotted-out shed with tetanus and building code violations). My sojourn in New Orleans, meanwhile, left the impression that it might have been the worst-run city in the First World, or the best-run city in the Third World — a colorful port town that drew in hurricanes, stray cats, and eccentrics of all stripes. The pungent, but not unpleasant smell of rows and rows of gaslights could suddenly transport me to a nineteenth-century European midnight. New Orleans might also have been one of the few places where I could have admitted to a stranger on the street that I was a believer in white advocacy — and still have a decent chance of receiving little more than a friendly shrug and a hearty: “Ça m’est égal. Bon temps!”

But it was also violent and heavily black. Some time ago I came across a statistic that claimed that one out of seven New Orleans residents had warrants out for their arrest. And I’ve never seen worse street gutters in a Western city. The standing waters looked and reeked of every conceivable human effluvium (and not just in the French Quarter). It was, in other words, the quintessence of Southern beauty and decadence, and those decadents’ simultaneous reverence and fear of decay. As Lady Nancy Astor once put it, the South was “a beautiful woman with a dirty face.”

“A Rose for Emily” (1930)

William Faulkner was perhaps the greatest writer of the Southern Gothic tradition, and his stories about a fictional town in Mississippi focused on its residents’ inability to escape the past. In “A Rose for Emily,” for example, Faulkner’s narrator described the titular character as “bloated, like a body long submerged in motionless water, and of that pallid hue.” The old house in which she lived “[lifted] its stubborn and coquettish decay above the cotton wagons and the gasoline pumps” alongside it. Its countenance was an “eyesore among eyesores.” [4] [7] After Emily’s father had died decades earlier and left her alone in the old house, a gallant mayor from a generation that still believed in the practice of noblesse oblige granted her exemption from city taxes. But representatives of the “New South” were determined now to collect them. Times, they thought, were different. These officials steeled themselves to call on the old spinster, whom no one had seen apart from her silhouetted form glimpsed at windows for years. And upon their entrance into Emily’s house, its doors thudded shut and enclosed them within a crypt. The parlor led to “a dim hall from which a stairway mounted into still more shadow. It smelled of dust and disuse — a close, dank smell . . . When the Negro [manservant] opened the blinds of one window, they could see that the leather [chair] was cracked; and when they sat down, a faint dust rose sluggishly about their thighs, spinning with slow motes in the single sun-ray.” [5] [8] Unable to weather Emily’s cold stare in this environment, the taxmen left empty-handed.

Emily hadn’t always been so forbidding. During her younger years, she had enjoyed the attention of one Homer Barron, a gregarious Yankee transplant, who’d come to the South for (Re)construction opportunities. He was a “big, dark, ready man . . . with eyes lighter than his face,” a description that hinted at his ambiguous ancestry (Did Faulkner mean “dark” in the way that white working men brown in the unforgiving southern sun? Or did he mean that the Yankee stranger was a mixed-race man who could “pass?”). [6] [9] Townsfolk often saw them riding around together in his horse and buggy. But they never married, and Barron vanished, leaving Emily alone and pitied once more. From then on, she became a recluse and seldom, if ever, received visitors. She grew fat, and her hair did not mellow into a soft shade of white, but it turned the color of implacable “iron-gray.” Not long after city officials had sought to persuade her to finally pay them her taxes, Emily died, and thus frustrated their efforts for good. Imagine their shock when, while clearing her house’s interior, townsfolk found locked in her upstairs bedroom the rictus-grinning corpse of Homer Barron, lying in a mummified state. One brave soul lifted from the pillow beside him a “long strand of iron-gray hair.” [7] [10] The bleak structure had been a tomb after all.

Emily was, of course, a symbol of the Old South — that “fallen monument” of faded beauty and health. [8] [11] Rather than allowing Barron the possibility of moving on, she’d persuaded her colored manservant to freeze time by lacing her lover’s dish with rat poison. Suggestions such as this of dubious racial ancestry, incest, and necrophilia have since become the favored motifs featured in works of Southern Gothic. Decomposition in all its meanings has pervaded the region’s literary masterpieces.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1947)

Tennessee Williams’ New Orleans-based play A Streetcar Named Desire made Blanche Dubois’ decomposing beauty (and sanity) central in a plot about male insecurities and female hypocrisies. [9] [13] The action followed Blanche’s arrival and stay at her younger sister’s flat after losing the Belle Reve estate (incorrect French for “Beautiful Dream”) to the federal government. It then traced the stormy relationship between Blanche and her sister’s Polish husband, ruffian Stanley Kowalski. Blue-blooded Blanche turned out to be a whore, and the red-blooded Stanley a loser. They might both have been justifiably called “sexual terrorists,” in each their way. The New Orleans evoked by Williams was that of the rough and working-class, but “raffishly charming” section of town “between the L&N tracks and the river.” The “first dark of an evening in early May” showed a tender blue that “attenuat[ed] the atmosphere of decay,” and the slow, “warm breath” of the river carried a scent of the bananas and coffee from the boats that brought their tropical cargo to this northernmost of Caribbean ports. [10] [14] It was a play that began with indolence and tinny “blue piano” notes set to women smoking on terraces and an “easy intermingling of the races” — the utopian image that liberals since Williams’ time have condescendingly imagined awaits us all at the quaint corner of Prole Street and Rue Multiculturelle. [11] [15] It ended with rape and madness.

Unlike Miss Emily, Blanche had no solicitous neighbors nor “the kindness of strangers” who were willing to go along with her nostalgia, to tip-toe around her eccentricities, and to make-believe that the third of July had ended the ‘63 campaigning season in victory, rather than defeat and impoverishment. No, the modern, “cosmopolitan” city did not indulge such ladies; it had them committed. The whole of Emily’s town turned out for her funeral, as if farewelling a “fallen monument” in a show of familial duty; none of Blanche’s friends or relations could watch as the doctor and his matron, both of them reeking of an “aura of the state . . . with its cynical detachment,” led her away to that most progressive of institutions: the asylum. [12] [16]

New England after Dark

I am unaware of an official name given to my Yankee counterparts’ gothic literature, so I will call it “New England after Dark.” If the South could never escape the “Civil War’s” long arms of memory, then New England never emerged from beneath the still longer shadow of Salem’s reckoning. “Witchcraft,” Emily Dickinson declared, “was hung in history,” but nonetheless it haunted Nathaniel Hawthorne, just as it gripped the imagination of H. P. Lovecraft. [13] [17] In the South, maybe some wicked “spaghetti-faced” man, burn scars licking across his cheek and brow, lay in wait to hack you into chum pieces for the gators. [14] [18] In New England, the Ancient Enemy, the Unnameable One, wanted nothing less than your eternity. Danger lurking in the Metacomet Ridge was not of this world. Though both regions fixated on putridity, it was the corruption of the soul that mattered most to the descendants of those first Calvinists at Plymouth Rock. The tales of New England after Dark were the creations of dissenters who both feared and revered the heretical.

Recent scholarship on colonial America has revealed that the places most susceptible to witch crazes in seventeenth-century New England were settlements that experienced higher numbers of Indian attacks. [15] [19] King Philip’s War of the mid-1670s had been particularly traumatizing. By summer’s end in 1676, more than half of New England’s colonial settlements had been reduced to sawdust, ash, and food for carrion. The Algonquian tribes pushed whites eastward until settlers felt upon their backs the foamy sea spray breaking on the coastal rocks. The Puritans and Protestant separatists of New England had always had a rather weak interest in converting their Indian neighbors to Christianity. A few men and women of God had established “praying towns” for that purpose, but most considered mission work not worth the effort when it came to the naked heathens of the wilderness. Some honestly believed that Indians were Beezlebub’s demon-children sent to afflict them. Indeed, colonists noticed that Indians made it an especial point to schedule their attacks during the Sabbath. According to one source, “[those] devillish Enemies of Religion, seeing a man, woman, and their Children, going but towards a meeting house [church], Slew them (as they said) because they thought they Intended to go thither.” Indians mocked the name of the Almighty, and “proudly exault[ed] over [their white victims]] . . . Saying, ‘Where is your O God?’” [16] [20]

There arose a moral panic within these intensely God-fearing people that the children of the old stock (or “Old Lights”), the first generations born on American soil, had inherited something of the New World’s barbarism. The idea that their progeny might degenerate into the bestial red men of the forests consumed their nightmares. It was against this backdrop of horrors that the Salem witch epidemic emerged in the 1690s (an epidemic that in reality encompassed a larger area of the Massachusetts Bay Colony beyond old Salem). It was also the beginning of New England’s obsession with the predatory supernatural.

The Scarlet Letter (1850)

Ah, the “Old Manse” on a hill, that New England structure belonging to scions of ancient names, that somehow got chillier indoors than out of them. In this setting Nathaniel Hawthorne first addressed readers and prepared them for his fable called The Scarlet Letter. Long ago the author’s “first ancestor . . . [that] grave, bearded, sable-cloaked, and steeple-crowned progenitor” arrived from across the sea, having fled England and its persecutions. But, Hawthorne wryly observed, “he was likewise a bitter persecutor” himself. [17] [21] By the time of his writing in the 1840s, Hawthorne’s native town of Salem was burdened with “dilapidated wharves,” “decayed wooden warehouses,” and “unthrifty grass.” [18] [22] Commerce had moved elsewhere, and federal tariffs had sunk the community into shabby listlessness. In Hawthorne’s day, all New England Yankees seemed to care about was the golden idol of filthy lucre, whose altars they worshipped in the swollen cities of Boston and New York. The world of the Puritans and their piety seemed to have vanished. Or had it?

As he rifled through the effects of a deceased Salem customs official, Hawthorne claimed that he came upon a curiosity. It was a piece of “fine red cloth” adorned with “gold embroidery . . . [and] wrought . . . with wonderful skill of needle-work.” Unable to look away from the oddly compelling item, he “cogitated on its function.” Was it an ornament meant to awe the Indians, or some remnant of a forgotten game? Following instinct, he raised the scrap and “placed it on [his] breast.” In that very instant, he felt a “burning heat as if it were not a red cloth, but red-hot iron.” A startled hand let it fall to the floor. The scarlet letter was glowing. [19] [23]

Hawthorne spent the next two hundred pages describing the true “function” of this possessed stigmata and its wearer, Hester Prynne, a woman who had lived in the harsher times of his “sable-cloaked ancestor.” Hester, he revealed, gave birth to a child out of wedlock (and after her husband’s presumed death at sea), and for this moral outrage, she suffered a public shaming ritual as directed by the town’s young Reverend, Arthur Dimmesdale. She made it worse for herself by refusing to name her “fellow-sinner,” even as she stood atop the scaffold. Puritan justice demanded on pain of damnation that she never remove the scarlet letter “A” (for “Adulteress”) from her bosom. The town elders released her from jail, but banished her to the woods; she and her child were literally and metaphorically outside the community of God’s Elect.

Years passed. Hester’s daughter and the living proof of her shame, Pearl, grew not into a human child, but into a cruel imp or woodsprite. She fixated on her mother’s scarlet letter in such a way that Hester was forced to conclude that her daughter was on an errand of God’s wrath, and was sent by Him to wring from the heart below her mark of shame every drop of her remorse. Meanwhile, the Reverend Dimmesdale endured the self-loathing of a hypocrite. It was he who had fathered Pearl and he who had lacked the moral courage needed to join Hester in her ignominy.

Hawthorne’s novel ventured into the eerie and weird, not only through the lurid powers of the Scarlet letter, but also through the character of Roger Chillingworth — the presumably dead husband of Hester Prynne who had returned in the disguise of a physician. During the years he’d been missing, Chillingworth lived amongst the Pequot Indians and learned their healing arts. He’d also, apparently, picked up a few of their black magic tricks. Torturing his “friend” Dimmesdale (whom he knew fathered Pearl), became his passion. “Had a man seen” Chillingworth during one of those agonizing sessions, “he would have had no need to ask how Satan comports himself, when a precious human soul is lost to heaven, and won into his kingdom.” [20] [24]

[25]

[25]You Can buy F. Roger Devlin’s Sexual Utopia in Power here. [26]

“The Dunwich Horror” (1929)

Hawthorne’s novels were examples of nineteenth-century Gothic Romanticism and weren’t classified as “horror” fiction, narrowly defined. But he did influence later writers of horror-proper, like H. P. Lovecraft, a fellow New Englander who was also obsessed with the supernatural. And like Hawthorne, Lovecraft wrote of “terrors [that were] of older standing. They [dated] beyond body — or without the body . . . the kind of fear [that was] purely spiritual.” [21] [27] Lovecraft’s “Dunwich Horror,” for example, took place in an area avoided by tourists and locals alike. During what would have been Hester Prynne’s time, “when talk of witch-blood, Satan-worship, and strange forest presences was not laughed at, it was the custom to give reasons for avoiding [Dunwich].” Alas, the narrator continued, “In our sensible age . . . people shun it without knowing exactly why.” [22] [28]

Calvinist “Old Light” fears had come to pass in that degenerated town, for “the natives [were] now repellently decadent, having gone far along that path of retrogression so common in many New England backwaters.” Lovecraft’s characters were gnarled and physically repulsive, but it was the sense of doom and invisible danger that haunted the glens and gullies of Dunwich and thus warned visitors away. Old legends “[spoke] of unhallowed rites and conclaves of the Indians, amidst which” those tribes “called forbidden shapes of shadow out of the great rounded hills.” [23] [29] In a story that mirrored in many ways The Scarlet Letter, “Dunwich” also began with the birth of a preternatural child whose parentage was a mystery. The child’s mother, Lavinia Whateley, never revealed its father’s name. She called her “goatish” bastard Wilbur. And Wilbur was not human. He aged exponentially faster than was normal; dogs loathed him; and the frightened townsfolk kept clear of him. After murdering his mother (and some said, feeding her soul to the evil ones who hungered for spirits in the dimension from whence he came), Wilbur dedicated his time to finding the black spells needed to unleash monsters of unimaginable darkness upon the world. Lovecraft’s Whateleys were apostates of a more extreme variety than Hawthorne’s hypocrites and fornicators. In New England after Dark, cries in the wilderness were not the calls of the faithful bringing the light of the heavenly Gospel to dark corners of the world; they were the bloodcurdling shrieks of damned souls as the darkness overtook them.

Midwest Grotesque

I shift now to the heartland, sometimes called the Midwest (or Middle West), but including the country on the plains. The people there have long had a catechism they’ve repeated:

- “Towns are safe and quiet”;

- “the folk are nice”;

- “nothing like that ever happens here”;

- and “no one locks their doors.”

Are these not the refrains that have every time been given by locals in the aftermath of some terrible event that rocked their tight-knit community to its foundations? New England and Dixie may have suffered from bizarre psychological afflictions inherited from the Old World, but Midwesterners scoffed at such hysteria and have carried on with their collective role as America’s backbone. And apart from some of its larger cities — Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis — it has also been one of the whitest areas of the country. Middle Americans, you see, were the real Americans. They have stood for the anthem and worked hard for a living and eaten apple pie at grandma’s house every Sunday.

But the thing about being in the middle of something is that you become a waystation — a passage — to one side or the other. And this reality has had consequences for the Middle West: Midlanders began to feel overlooked. As described in classics such as The Great Gatsby, the coasts have drawn away young people seeking glamor elsewhere. More ominous than this was the fact that waystations have always been pit stops for strangers and transients (the 1930s Cleveland Torso Killer, who left dismembered bodies near the city’s railroad tracks, comes to mind). Not everyone passing through has had innocent intentions — and grifters have taken advantage of unsuspecting people used to safety, tranquility, and unlocked houses. Dreams broken and faiths shaken made Midlanders fear and revere their interiors. What lurked deep within the core of things? What hidden hopes and malice have snared men’s hearts? For Midlanders, being the core — the center — of America has been both their blessing and their curse. Their constant search was for home — that womb in the country’s middle where once they felt safe.

In Cold Blood (1966)

Holcomb, Kansas was one such waystation in the late 1950s that “few Americans . . . had ever heard of.” And “like the waters of the [Arkansas] River, the motorists on the highway, and like the yellow trains streaking down the Sante Fe tracks, drama . . . had never stopped there,” but everyone passed through it, unremarked and uneventfully. Its inhabitants were content to “exist inside ordinary life — to work, to hunt, to watch television . . . to attend the 4-H Club.” [24] [30] But something did stop there in the autumn of 1959. Something that made townsfolk, “theretofore sufficiently unfearful of each other to seldom trouble to lock their doors,” regard their neighbors “strangely, and as strangers.” [25] [31] For those unfamiliar with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the true story of the Clutter family murders in the tiny Kansas farming community, Holcomb’s fate will disturb their sense of security.

For some time, neither the police nor the Kansas Bureau of Investigation knew who had raided the Clutter home in the early morning hours of November 15, then shot at point-blank range each of their hogtied victims (Herb and Bonnie Clutter, along with their children, Nancy and Kenyon) in the head. What had these intruders come for? Suspicion engulfed the town. Some thought Nancy’s boyfriend Bobby was guilty, while others looked askance at the Joneses — the wealthiest family in wheat and energy-rich Holcomb and just down the dusty road from the Clutters — and concluded that old Taylor Jones must have been the real target. Whomever it was, the fiend would come back for him.

Townsfolk gathered at the local hotspot Hartman’s Café to further speculate. “Just a bunch of old women,” the postmistress of the town scoffed at the gathered farmers, “who have nothing to do but sit around and scare each other” now that winter was on the way. It was time, she declared hotly, “for everyone to stop wagging loose tongues . . . and telling plain-out lies . . . Look around you! Rattlesnakes. Varmints. Rumormongers!” A transplanted Englishwoman, whose husband had lost their hereditary home due to British “death duties,” and had since decided to try their luck in America, added that though she was “without regrets” and absolutely “adored!” their new life in the back of beyond, she’d “never known such bedlam.” London bomb raids had nothing on the “train whistles. Coyotes. Monsters howling the bloody night long. A horrid racket . . . and after dark, when the wind commences, that hateful prairie wind, one hears the most appalling moans . . . if one’s a bit nervy, one can’t help imagining — silly things. Dear God! That poor family!” [26] [32] Others announced their plans to “pack up and leave” Finney County for good.

Even though the two culprits — prison buddies (one of them a Cherokee half-breed) whom no one from the town had ever heard of — were caught, tried, and sentenced to hang, the damage to Holcomb had already been done. Oh, we’re glad the case was solved, said one resident, but “we still feel others may be involved . . . [and] plenty of folks are still keeping their doors locked and their guns ready.” After marinating for “seven weeks amid unwholesome rumors, general mistrust, and suspicion . . . a sizable faction [of the townsfolk] refused to accept that” the two murderers were not from among themselves. There was agreement on one thing: “after what happened to Herb and his family . . . something around [there] had come to an end.” [27] [33] Those six shotgun blasts had stolen from Holcomb four lives and its innocence.

[34]

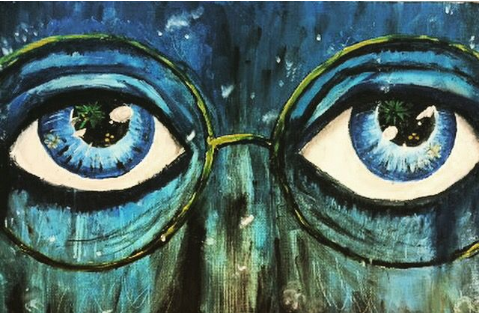

[34]“Over the ash heaps the giant eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg kept their vigil” — The Great Gatsby, 95.

The Great Gatsby (1925)

Capote’s “true crime novel,” as the book was called by the press, was a dark tale that, by the end, became a meditation on questionable court procedures and the death penalty. The author could not maintain an outsider’s detachment, and was sucked into the middle — pulled into the interior lives — of the criminals, who were themselves at the center of this Middle American whirlpool of a horror story. In some ways, In Cold Blood was The Great Gatsby’s mirror. Both revolved around the murder of heartland Americans, but Truman Capote’s book began with a crime, while F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ended with one. The Clutter family’s demise attracted famous authors and the international press to the scene of the murder, while Jay Gatsby’s fictional murder attracted the attention of less than a handful of mourners and no press at all. The former story was told by a narrator from outside the Middle West, who traveled from the country’s periphery to its conservative, cyclical, predictable, interior; the latter was told in the voice of a narrator (Nick Carraway) who hailed from inside the Midwest. Drawn by the excitement of flappers and gin in New York, Carraway traveled to America’s coastal periphery. Every hour was cocktail hour, and every season cause for a party. As he admitted, “Instead of being the warm centre of the world, the Middle West now seemed like the ragged edge of the universe.” [28] [35] The center of things, he initially believed, was the Empire State.

Carraway fell in with other expatriate Midwesterners, Tom and Daisy Buchanan, as well as the mysterious “Jay Gatsby” (though the bombshell revelation that enigmatic “Jay Gatsby” was really Jimmy Gatz from small-town, USA came later). Why Tom and Daisy “came East [he didn’t] know. They . . . drifted here and there unrestfully wherever people played polo and were rich together . . . [he] felt that Tom would drift on forever seeking, a little wistfully, for the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.” [29] [36] An antsy manchild, a nomad who, ironically, never left his college fraternity. An Odysseus without a purpose, or a port. This Lost Generation of young people were drifters not because traumatic experiences during the Great War had doomed their idealistic dreams, but they were drifters because their idealistic dreams had doomed them to wander forever in pursuit of mirages. By the end, Carraway had concluded “that this [was] a story of the West, after all — Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and [he] were all Westerners, and perhaps [they] possessed some deficiency in common which made [them] subtly unadaptable to Eastern life.” [30] [37] The character most suited to “Eastern life,” was, in fact, a “flat-nosed” Jew named Meyer Wolfsheim, a criminal kingpin and racketeer who had “fixed” the 1919 World Series and helped set-up Gatsby’s bootlegging enterprise — the quintessential and highly “adaptable” New York Jew. But for Carraway, the glamour of the big city faded, and he resolved to book a passage homebound for the interior and leave the gleam and grit of New York behind in exchange for a train to St. Paul. In words that Holcomb residents would later echo precisely, Nick Carraway determined: after the murder, “after what happened . . . something around here had come to an end.” [31] [38]

LA Noir

At last, we come to another end, to the place where we finally ran out of continent: the Golden State. There was nowhere to go next, no place left for the restless American energy to spend itself, so Californians never settled. Instead, they tried everything and experimented endlessly in a series of perpetual reinvention cycles that “[shucked] off the past like last year’s frock.” [32] [39] They became manics. Freaks. Weirdos. The Midwest’s foil, even as the bloated city by the sea filled with Middle American migrants. Unlike reactions to terrible events in Middle America, few in LA have ever been surprised by even the most outlandish and cinematic of outrages. People went to LA not to settle down, but to jump off a cliff in the hopes that they would fly, or at least plunge harmlessly into the friendly waters off Santa Monica.

California has been treated and seen in American history and culture as the land of El Dorado. Gold in the hills and silver on the screens. The Rushes of the mid-nineteenth century lured Easterners to go by way of boats to Central and South America, and then on to the West Coast, where they could pan for precious metals. Others, like the Donner Party, hitched their wagons with hopes and horses and set off to complete America’s Manifest Destiny. It has since attracted a large population of blacks, Hispanics, and Asians — a messy, polyglot brown stew of multicultural madness. This past has given California a trove of colorful success stories. But it also resulted in a seedy underbelly of grifters, cult leaders, and killers, all ambitious as Lucifer, and who all preyed on the naive and the desperate. There was a new “Crime of the Century” every other month. Rootless people make easy killers and easier victims. LA was full of opportunists who both worshipped and feared the hustler.

L. A. Confidential (1990)

In another, more eloquent age, LA was known as El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles, “The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels.” By the 1940s and 50s, the patroness to whom Spanish monks had dedicated its founding had packed up and left, deciding that godliness in Los Angeles was a lost cause. The city’s patrons were instead LA Noir writers like Raymond Chandler, whose novels exposed the treacherous men and the even more treacherous women looking to score. This, in turn, inspired later neo-noir author James Ellroy to plumb the depths of postwar California in works such as The Black Dahlia and L. A. Confidential. The latter story began with a violent shootout between a fugitive called Buzz Meeks and the men who had double-crossed him. Meeks was on the lam due to some poor choices: he’d angered a powerful drug dealer and killed a cop. Out of options, Meeks hid in the El Serrano, a fleabag motel with “cobwebs, rats, bathrooms with clogged-up toilets, rotted food, [and] magazines in Spanish, [for] the [drug] runners . . . used the place to house their spics en route to the slave farms up in Kern County.” [33] [40] According to the “runners,” a few men were due to collect Meeks, and drive him outside town where he could then hightail it from everyone who wanted him dead. It was, unfortunately, a set-up. The last thought that occurred to Meeks as he lay bleeding out on the stained carpet and surrounded by the “beaners” he’d managed to take with him down to the “big sleep,” was that “the El Serrano Motel looked just like the Alamo.” [34] [41] Yes, Meeks, but without the immortal glory. Californians always did have delusions of cinematic grandeur.

Ellroy’s Confidential cop drama included a tidbit about “Dr. Frankenstein,” a heinous case that haunted Detective Ed Exley twenty years after the murders. Children: “Mexican, Negro, Oriental — three male, two female — [were] found dismembered, the trunks of their bodies discovered in LA area storm drains. The arms and legs [had been] severed, the internal organs removed.” The LA press dubbed it the “Dr. Frankenstein” murders. Exley determined that “the fiend [was] recreating children with stitching and a knife . . . he [wondered] what the killer [would] do for a face. He [found] out a week later.” Willie Wennerholm, a child star, was kidnapped from a “studio tutorial school,” and left decapitated by the railroad tracks. The culprit turned out to be a paroled child molester “with a vampire fixation.” [35] [42] Maybe I read too much into the passage, but the description of this over-the-top serial killer seemed to neatly symbolize LA itself. The city was a Frankenstein monster made up of multi-culti detritus all stitched grotesquely together in a sick semblance of reality. Don’t worry, Dr. Frankenstein said, He will walk and talk like a real boy! It was literally and metaphorically topped off with the head and model-looks of a white movie star.

Ellroy rendered the monstrous in staccato, emotionless prose so that the reader had as much of a chance of hiding or escaping from LA as his broken characters had dodging bullets. His sentences were gunshots. Other genres, like Southern Gothic, may have featured “good-ole-boy” lawmen, but their crookedness seemed petty next to the profound corruption afflicting the city officials and LAPD of Ellroy’s urban underworld. In LA, folks went to prison for tax evasion but got away with murder.

Since Ellroy published his modern classic in 1990, LA has since experimented with creative policing strategies that helped level their thirty-year-long national crime spike, but drugs still moved freely on the streets, and gang violence made the nineties a “decade of death” for the city’s residents. LA also endured the rise of “gangsta rap” and the Rodney King riots; its sensational atrocities, including O. J. Simpson’s double-murder and subsequent sham trial, presaged the country’s tacky love affair with “reality TV.” The city has only become more multiracial and less “Midwestern-white” over time. According to Statistical Atlas, 2018 metro Los Angeles had an estimated population of almost 13,200,000 people. Non-Hispanic whites were just over 30 percent of the population, while Hispanics comprised nearly 45 percent. Asians outnumbered blacks by 15 percent to just under 7 percent. [36] [43] Unsurprisingly, it has remained a prime setting for more recent neo-noir writers who haven’t been afraid to tell the truth about modern LA.

“The Golden Gopher” (2007)

In her short story “The Golden Gopher” (an allusion to both the “Golden State” and the animal associated in American Indian folklore with messengers from the underworld bringing news of death), Susan Straight used the semi-autobiographical narrator “FX” Antoine to comment on life in California’s multi-culti Mecca. I do not know Ms. Straight’s political leanings, but her portrait of twenty-first-century Los Angeles was that of a Third World tenderloin. The word “Brazil” appeared multiple times. All of Straight’s troubled characters were non-white, but honest, and none of them blamed whites for their dysfunction. FX’s people were from Rio Seco by way of Louisiana. When she was a teenager, FX had stowed away in the back of one Grady Jackson’s stolen car, because he was lighting out for LA — the city that promised freedom and amnesia. But “all the things [she] hated” and had tried to run from “when [she] was young, [she] wanted now. [She] could smell the still-thin exhaust along the street. It smelled silver and sharp . . . Like wire in the morning when [her] father and brothers unrolled it along the fenceline of [their] orange groves.” [37] [45]

Nevertheless, FX couldn’t wallow in nostalgia that day, for she had a mission. Her childhood friend and Grady Jackson’s old flame, Glorette, had died — strangled and left in a grocery cart behind a tapas cantina. FX had a duty to find Grady (whom she’d not seen in over a decade) and tell him the bad news. As she ventured deeper into the city, she passed teeming numbers of homeless — all walking or stealing sleep in requisitioned shade. But then, everyone was homeless in LA. FX “was like the homeless people, too” for “no one knew who [she] was. No one knew what [she] was. People spoke to [her] in Farsi, in Spanish, in French. [Her] skin was the color of walnut shells. [Her] hair was black and straight, and held tightly in a coil. [Her] eyes were slanted and opaque.” So, when they spoke to her in one of hundreds of languages and dialects peppering the downtown air, she “just smiled and listened.” [38] [46] She looked like anyone and no one: “a sista, a homegirl, a payasa. Belizean. Honduran. A Creole.” She belonged anywhere and nowhere, and she “needed to walk every day . . . needed the constant movement” — a city zombie who could never go back, never go home. [39] [47] FX was America’s future: the end-product of socially-engineered race mixing that will result in a country filled with degraded ancient Egyptian look-alikes. No wonder she blended in, for the city itself was everything and nothing, too, “a thousand little towns. Entire worlds recreated in arroyos, strawberry fields and hillsides . . . Downtown had canyons of black and silver glass . . . and its own favela . . . Brazil, that’s what Skid Row looked like. The houses made of cardboard, the caves dug out under the freeway overpasses, the men sprawled out on the sidewalk . . . cheeks against the chain-link.” [40] [48] Dr. Frankenstein’s stitching had grown more feverish.

FX found Grady washing windows for the Golden Gopher bar where his sister worked the counter. He hadn’t aged well. But he still carried a torch for Glorette, that much was clear, and before FX could work up the nerve to tell him the news, he began to spout all of the unconvincing lies men have told themselves and others when they’ve tried to make believe they were not in love. FX sighed. “She’s dead, Grady. Somebody killed her back in Rio Seco.” [41] [49]She was met with silence, then Grady turned away. He began walking and disappeared into the city, joining the scores of homeless who could never go home, but were doomed to wander the underworld forever. No one saw him again. The ambush wasn’t as loud or as bloody as the trap sprung on Meeks at the El Serrano, but it was just as final. LA had devoured another of its orphans.

Conclusion

If there is a commonality between Southern Gothic, New England after Dark, Midwest Grotesque, and LA Noir — besides murder, sex, and an amusingly chronic gripe about taxes — then it must be the fact that each evolved from and portrayed the unraveling that so often occurred due to direct contact with alien others. As an emotion, horror is a combination of two things: fear — that primal instinct that warns us of danger and wills us to survive attacks (hide, run, fight) — and anxiety, which emerges from our intellectual faculties and manifests in our personal neuroses and social hang-ups. [42] [50] The gothic tales this essay has discussed were horrifying because they exploited both deep, animal fears, as well as the high strung and human social anxieties particular to region and blood. Something that once seemed pure twisted into something perverse (I say “seemed,” because the “virginal” New World was never thus). The sharing of space with quasi-domesticated black Africans cursed the South with death and defeat, then fouled the waters of its fetid marshes. The Puritans of New England arrived with clear eyes, but they too suffered corruption as a result of their conflicts with feral red men, their righteous pride, and their proximity to the woods where dwelled those “devillish Enemies.” Middle American towns and settlements were the constant scenes of the comings and goings of strangers by rail, wagon, horse, and car; and sometimes this mobility caused townsfolk to view their own neighbors as the real strangers. The megalopolis on the West Coast became a hub of drifters and nomads — a city that swelled with aliens and the alienated, thus resulting in over-crowded emptiness.

Contra Goethe’s admonition, we haven’t “guarded well against” much of anything (least of all overrun borders), and we now have no place left to run. Jay Gatsby wanted to “repeat the past,” but, of course, it was the fact that he could not escape it, even if he tried, that doomed him. [43] [51] We wanted a country of men without masters, but as Lawrence said bluntly, “There is always a master.” [44] [52] Like our European ancestors, we are stuck on a continent with the monsters and strife of our own design, and they are the masters, and we their slaves.

No, Herr Goethe, America’s story was always darker than your “Continent, the old,” for our “castles” were cracking, “our arms [outstretching]” toward the wind-whispered “panders” of siren-calls, even before the ink on Virginia’s Royal Charter, or the Mayflower’s Compact, had dried. [45] [53]

Notes

[1] [54] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “To the United States,” trans. Stephen Spender, in The Permanent Goethe, ed. Thomas Mann (New York: Dial, 1953), 655. For the German original, see Insel Goethe: Werkausgabe, ed. Walter Höllerer (Frankfurt: Insel, 1970), 224–25. This was the European romantic view of the United States.

[2] [55] D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (London: Martin Secker, 1920), 57. This is essentially 200 pages of diatribe against what Lawrence perceived to be the American character, thinly disguised as literary criticism. By contrast, Lawrence’s was the very un-romantic view of the United States.

[3] [56] John Berendt, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil: A Savannah Story (New York: Vintage, 1994), 28.

[4] [57] William Faulkner, “A Rose for Emily,” in Forum (April 30, 1930) pp. 12-23, 12.

[5] [58] Ibid., 15.

[6] [59] Ibid., 17.

[7] [60] Ibid., 23.

[8] [61] Ibid., 12.

[9] [62] For those who have seen the 1951 movie, rather than having read the play: in the Warner Brothers production, Vivien Leigh reprised for audiences the Southern Belle archetype that made her famous a decade earlier in Gone with the Wind (1939). This time she was not the fresh-faced and resourceful Scarlett of the nineteenth century, whom Leigh had played during the bloom of her youthful loveliness; just as Streetcar’s Blanche was a wilting 1950s aristocrat, and plagued by neuroses, so Leigh herself had aged and become mentally fragile. Her foil Marlon Brando, meanwhile, performed the role of Stanley at the peak of his brawny beauty and sex appeal.

[10] [63] Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire (New York: New Directions, 2004), 3.

[11] [64] Ibid., 3.

[12] [65] Ibid., 171.

[13] [66] Emily Dickinson, “Witchcraft Was Hung, in History [67],” Manuscript 528, Amherst College Manuscript Collections.

[14] [68] The “Spaghetti Man” is a reference to Nic Pizzolatto’s Louisiana-set True Detective, Season 1 (2014); the primary antagonist was referred to by a child victim as “the Spaghetti Man,” due to the burn scars that marred his face.

[15] [69] See, for example, Mary Beth Norton’s In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis in 1692 (New York: Vintage, 2003).

[16] [70] Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage, 1998), 105.

[17] [71] Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2001), 7.

[18] [72] Ibid., 8.

[19] [73] Ibid., 29-30.

[20] [74] Ibid., 121.

[21] [75] This was taken from Charles Lamb’s Witches and Other Night Fears that Lovecraft chose to preface the story: H. P. Lovecraft, “The Dunwich Horror [76],” (1929), 1.

[22] [77] Ibid., 1-2.

[23] [78] Ibid., 2.

[24] [79] Truman Capote, In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences (New York: Vintage, 1993), 3.

[25] [80] Ibid., 3.

[26] [81] Ibid., 70-71.

[27] [82] Ibid., 73.

[28] [83] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Scribner, 2003), 5.

[29] [84] Ibid., 6.

[30] [85] Ibid., 134.

[31] [86] Ibid., 57.

[32] [87] Denise Hamilton, “Introduction: City of Angels and Demons,” in Los Angeles Noir, Denise Hamilton, ed. (New York: Akashic Books, 2007) pp. i-vii, iii.

[33] [88] James Ellroy, L. A. Confidential (New York: Mysterious Press, 1990), 4.

[34] [89] Ibid., 6.

[35] [90] Ibid., 47.

[36] [91] “Race and Ethnicity in the Los Angeles Area, California [92],” from American Statistical Atlas (September 14, 2018).

[37] [93] Susan Straight, “The Golden Gopher,” in Los Angeles Noir, pp. 179-208, 183.

[38] [94] Ibid., 186-87.

[39] [95] Ibid., 185.

[40] [96] Ibid., 188.

[41] [97] Ibid., 206.

[42] [98] Our intelligence is a double-edged blade. It has blessed us with the imagination capable of solving complex problems. Unfortunately, our intelligence might be even better at conjuring problems and fears out of air.

[43] [99] The Great Gatsby, 83.

[44] [100] D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, 10.

[45] [101] The Great Gatsby, 189.