Chapter 8 of Charity’s Blade: “Give me your hand, dear.”

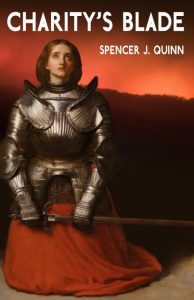

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledCharity’s Blade

The Free Speech Library, 2020

Available for purchase here [2].

See Kathryn S.’ review of the novel here [3].

The poster had gone up easily. Charity got the angle just right on the first try, putting its top edge perfectly parallel with the ceiling. It now dominated the wall above her headboard and projected itself between the two windows of her bedroom. She could have placed it on the wall opposite the door, but then it would have been immediately noticeable from the hall. Somehow that seemed too bold. But she had just turned fifteen, and that summer had expanded into a D cup, which meant that her bra size had finally exceeded her mother’s. She had finally grown taller than her mother as well. Her grades were excellent. As a high school sophomore, she was taking AP Spanish and biology courses. She was a starting player on her volleyball team. She was diligent in her musical studies as well. She already had control over the clothes she wore, the books she read, the music she listened to, and the movies she watched. And her parents approved of all her friends. Why wouldn’t they approve of this poster too? It wasn’t as if it were in any way vulgar or obscene.

Feeling that she would need her parents’ approval for a poster put a damper on her self-esteem. It nagged at her constantly. It belittled the image of herself when she held it up against her peers, who seemed to revel in the freedoms their parents bestowed on them. She actually feared how her parents would respond to it. But what adolescent lives in fear of her parents these days? She assured herself that this was an antiquated state of affairs. She chided herself for indulging in such thoughts, even as she was pressing the thumbtacks into the walls.

She stepped back to view it in the context of her entire room: the vacation photographs on her dresser, the antique gold gilt oval mirror which used to belong to her great-grandmother in Virginia, the publicity shots and magazine cutouts of her favorite actors and actresses, the photographs of herself and her best friends scattered among them. In the middle of it all, and now the largest item in her teeny-bopper collage, was the poster promoting her high school boys basketball team. All of the players were black, with two receiving national attention at the time. These two figured prominently in the poster: one with an outstretched tongue as he delivered an emphatic slam dunk, and the other as he released the game-winning shot in the previous year’s state championship game.

Charity couldn’t help it. She felt a pubescent yearning for both boys, sweet and agonizing. She admired their primal athleticism and their success, especially that of Timothy Jamelle Bell, the six-foot-four guard who drained the twenty-footer to clinch the state championship. She wouldn’t dare share her feelings with her parents or sisters. She even kept quiet about it with her girlfriends since she felt she needed to compete with them for the attention and affection of these two future superstars.

That Bell couldn’t get himself above a 2.4 GPA throughout his high school career, even with the help of a team of tutors, didn’t concern her. Neither did the fact that the other boy, the team’s six-foot-nine center Jamaal Smith, had dodged charges of attempted rape and assault while intoxicated at a party the previous summer. As he was overpowering the college-aged sister of a classmate in her bedroom, her twenty-three-year-old boyfriend heard her screams and came rushing in. With his underwear down to his ankles, Jamaal stood and clocked the five-foot-ten man with an overhand right, knocking him out and breaking his jaw in two places. The case never went to trial since the concussed man could not remember the assault. The only other eyewitness, the young woman whom Smith was in the process of raping, recanted under pressure from Smith’s attorneys. They, of course, had been paid for in part by the nearby state university, which was keen on recruiting Smith. The official story framed the attack as self-defense and portrayed Smith, who had just turned eighteen, and the young woman as about to engage in consensual sex. Rumors spread by the partygoers and by disgusted members of the legal profession in town, however, told a more honest story. But because both the victims and perpetrator in this crime were black, the story died in the local press after a week.

Like most of the students in her school, Charity was aware of these rumors, yet they seemed so distant and unrelated to what she knew. Both the victims were grownups and not in her scholastic circles. Those two boys, however, she had known since elementary school. She attended classes and social functions with them and had grown familiar with them. She simply could not believe negative stories about either of them. Anyway, to do so would have been racist, and to be called a racist would have introduced unwanted complications into her life.

After considering the poster for several moments, she decided that she approved of it and then went to bed.

* * *

Charity’s mother Julia had never been satisfied with her hair. For as long as Charity had known her, the woman never stopped complaining about it, and her hair never stopped changing. Julia had tried nearly every shade between blonde and brown, as well as an entire catalog of styles. She always looked critically at her hair in the mirror, always adjusting it and letting it fall this way or that. Other than her stylist, she never let anyone touch her hair — not even Paul, her husband of nearly twenty years. Hair was a serious matter for Julia. She thought about it, read about it, even theorized about it from time to time with her circle of church friends. Selecting a hair product in specialty stores often forced her into chess-master levels of calculation. Her forethought almost always bore fruit, however, given how good she usually looked. To an outsider, it would seem that Julia simply had a flair for hair. Her immediate family, however, witnessed the frustration and sacrifice behind it and had long ago stopped attempting to plumb the depths of this strange obsession. Everybody was happier that way.

Both of Charity’s parents seemed quite young to her when she was fifteen. They had married when Julia was just out of college and Paul was a young Army officer in his late twenties. Knowing that Paul would sooner or later be stationed away from the family, they had three children in quick succession — all healthy, normal girls — with Charity as the red-cheeked, button-nosed caboose.

A particular photograph of Julia had always transfixed Charity. It must have been taken when she was twenty-one or twenty-two, shortly before meeting Paul. She was sitting outdoors in a wooden chair with her right forearm resting on the armrest and a lit cigarette in her hand. She was looking slightly away from the camera, and for once, her hair seemed to fall in natural tangles to her shoulders. Her neck was long and her chin raised. She wore lipstick and no other makeup as far as Charity could see. She didn’t smile, either. There was something cool and scrutinizing about her eyes. Half closed, yet aware, they seemed to say that she hadn’t yet grown tired of waiting for you to impress her.

This was so far from the woman Charity knew. The mother she knew, a woman in her early forties, would have indulged her children in every aspect of their lives if not for her husband. An effusive yet gentle housewife, Julia Miller loved being a mother. She cooked and cleaned as if living in a 1950s sitcom. There was no place she wouldn’t drive her children, and no time was too early or too late. In her daily life she doted on them obsessively, always inserting a benign interest into everything they did: music, sports, dance, clubs, travel. She made sure there was always something going on, but lacked the will to impose anything in particular. She left that to Paul, whom she supported with poignant obedience. Until she was fifteen, Charity had never seen her mother seriously irritated, let alone angry. She knew enough about human nature even then to recognize how rare this was and had to make a conscious effort not to abuse her mother’s love or take her for granted.

* * *

Charity was lounging on her bed with her device when her parents entered her room. It was two nights after the poster went up. Julia, in a white blouse with the sleeves rolled up and a flowing burgundy skirt, kept her mouth tightly shut as she followed her husband into the room. She had her head turned, peering at her daughter with one eye instead of two. Her hair was made up in an impeccable updo with long, wavy bangs stretching past her jawline. Right away, Charity knew what this was about, but feigned ignorance as she pulled herself away from her device. She also realized why her parents had sent her sisters shopping twenty minutes prior. They wanted the house empty for what they were about to do.

Paul snatched the back of Charity’s chair and plopped down on it backwards, leaning forward on his elbows — an annoying habit of his. Julia, however, folded her arms and stood aloof. Paul did most of the talking, but throughout the confrontation, Charity had to resist the urge to continually look at her mother.

Paul shot his eyes at the poster. “Care to tell us about that?” Charity always wondered how her father’s hair could go gray while his eyebrows remained starkly black.

“It’s the boys basketball — ”

Paul smiled hastily. “I know. Why do you have it up?”

“Why can’t I have it up?” Charity asked back.

Paul closed his eyes and sighed, for a moment eradicating all the wrinkles around them. With his shirt unbuttoned at the collar and scruff on his wide, manly jaw, he seemed ready to end his day. It was almost nine in the evening on a Wednesday. “Answer my question or I am going to get angry.”

Charity shrugged, demonstrating an inkling of an attitude. “I’m showing support for our school’s basketball team. Why can’t I show support for our school’s basketball team?”

“Because we don’t think it’s a good idea to have posters of young black men on your wall.”

“Why not?”

“We’ve discussed this,” Paul said, keeping a firm lid on his temper. “We don’t need to discuss it again. Now, your mother and I think — ”

“No, let’s discuss it again, Dad!” she said, revealing her well-rehearsed indignation. She stood because her drama teacher once told her that voices carry more effectively while standing. “Because we just haven’t talked about it enough, have we? Have we? About how much you hate black people and how inferior you think they are, and all the things they do that you don’t like. So, yes, let’s talk about it!”

“Are you done?”

“Not if you’re still here telling me what I can or can’t put on my wall.”

Paul held his hand out, ostensibly as an appeal to reason. “But we, as your parents, have that right, don’t we?”

Charity took this as a sign of weakness and pounced. “I am getting straight As! I am starting on the volleyball team! I practice piano a half hour every night! I volunteer at church! I do all my chores! And I never complain and I never get in trouble!” She emphasized her position with a melodramatic slap to her breast. “What more do you want from me?”

“We want you to take that down,” he said, pointing to the poster. “We have nothing against black people, but we just do not want to encourage teenage adoration of young black men.”

“But I’m not dating them!” she argued. “You’ve told me you don’t want me to date black boys. And I never have!”

Paul waited a moment and then looked at Julia before responding. He had just gotten home after another twelve-hour day. His weariness was beginning to show. “But you’re still young, Charity. That can change. And if we let you keep this poster — ”

“That’s ridiculous! Do you really have so little faith and trust in your own daughter that you won’t take her at her word?”

“Look, what we want — ”

“What I want is to be able to decorate my room the way I want to! I think I have earned that right!”

As soon as her exhausted father sighed and let one eye droop, Charity knew that she had won. Entrapped in a web of logic, he wriggled for a moment and then gave up. He appealed to Julia, who hadn’t changed her stern expression since entering the room. “Anything you want to add?”

Apparently, this confrontation had been more her idea than his. She sniffed in disgust and left.

Paul waited a few moments and then nodded. He got up and swiveled Charity’s chair beneath her desk. “Okay, fine, you can keep your poster,” he said, pointing his finger. “But as long as you obey the rules. Do you understand, young lady?”

Charity said nothing. The victor does not respect ultimatums from the vanquished. She fell on her bed and smiled the moment her father left. He hadn’t lingered long.

* * *

After falling asleep that evening, Charity’s next memory was waking up and seeing her desk lamp turned on. Her mother, in her white bathrobe, sat down on her bed, causing a shift in the mattress. Charity noticed that her updo had loosened and was tilting slightly to the side. Without her hair combed, her mother seemed engulfed in an aura of Medusa curls. And her expression — that cool, selfish, scrutinizing expression — sprang straight from that old photograph.

“Wake up,” Julia said.

Charity blinked the sleep out of her eyes and propped herself up on an elbow. “What is it?” she asked.

“Give me your hand, dear.”

“What?”

“Give me your hand,” Julia repeated.

An insistence in her tone caused Charity to instinctively obey. Shortly after giving her mother her right hand, however, she felt a searing pain on her forearm. Something hard, smooth, and extremely hot was burning it. The pain came twice: once on the arm itself, which caused her to shriek and pull away, and once in her young and still-sleepy mind, which could not process the shock. Julia held her daughter’s arm in place for what seemed like a sadistic two seconds before letting go.

Charity continued shrieking as she kicked off her covers in a panic and tried to roll away from her mother. She did not get far. Julia crawled on top of her, placing her daughter’s torso between her knees and pinning her in place. She then pointed the hot, smooth object at her like a sword. Charity could feel its heat and hear the electricity buzzing through it. She could also smell the skin it had just burned. She stopped shrieking and started sobbing once she realized what it was: her mother’s battery-operated curling iron.

“Take down the poster,” Julia commanded, her voice thin, quiet, and mean. Charity continued sobbing rather than answer. The pain and shock was too great for her to coherently respond. Julia inched the iron closer. “I said, take it down!”

Charity sank her head as far as she could into her pillow and squeaked, “Okay! Okay!”

Julia removed a knee to let her daughter get up, still aiming her improvised weapon at her. She was breathing heavily, nearly exhausted. But her determined eyes, slicing through her silhouette like glittering blades, told Charity that she was going to see this through. Charity stood on the bed and faced her mother in open-mouthed terror, holding her burned forearm.

“Now!” Julia commanded, waving the iron. Immediately, Charity obeyed, ripping the poster down and sending thumbtacks flying.

The light turned on. Charity looked, but Julia did not. In the doorway stood her stunned father and sisters. “What is going on?” Paul shouted.

Charity seemed inclined to answer, so Julia waved the iron once again. “Tear it up. Tear it up!” she ordered. Charity did, now apologizing profusely through her sobs. She fell to her knees as colorful confetti littered her bed and the floor around her. As Julia stepped down off the bed, Paul tried to take her by the arm. She spun around and pointed her wand at him as well. Had he not stepped back in time, she might have burned him on the shoulder.

Still breathing heavily, but calming down, Julia turned once again to her daughter. Her updo was barely hanging on. With the strain of the moment disfiguring her starkly lit face, she seemed too old for such a stylish conceit. Yet there she was. “You best remember, young lady,” she said with pitiless composure, “that there are people who came in this family before you. And you owe them everything!”

Paul tried again to take his wife by the arm, but she shrugged him off. She looked once more at Charity, that detached scrutiny in her eyes burning an impression in her daughter’s mind as much as the curling iron had in her arm. With her entire family staring at her dumbfounded, Julia silently left the room.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [5].

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.