The Uncanny Digital Valley

Posted By Jim Goad On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,389 words

Back in the year 2000 — before the advent of smartphones and the existence of social media in any significant sense beyond a humble smattering of BBS message boards — I and the other convicts at Oregon State Penitentiary caught wind of a new super-max prison they were building in the state’s remote eastern regions.

The primary mode of punishment at this new facility was sensory deprivation. You could receive visitors, but they’d be in another room at the prison, and you’d only interact with them via a video screen. You could receive mail, but you weren’t allowed to touch it — again, they’d show it to you on a screen.

We were horrified in unison. What sort of sadistic psychopath came up with this scheme? We’d all endured prison, for fuck’s sake, and it’s fair to assume most of us had suffered hard knocks since childhood. But this sounded cruel and unusual, even to us.

Twenty years later, it’s how most people interact — onscreen rather than in person. The whole world is trapped in that high-surveillance sensory-deprived super-max panopticon and doesn’t even realize it, much less seem troubled by it.

When I got divorced eight years ago and walked blindly into a social blizzard seeking comfort, I made the acquaintance of a blue-eyed girl from Indianapolis, which is 600 miles from where I live in Georgia. We had an intense and tumultuous relationship lasting twenty months. Sometimes I’d fly to Indianapolis, sometimes she’d fly to Atlanta, and sometimes we’d drive and meet one another halfway. As the romance crumbled, I tried to tally exactly how much time we’d spent in one another’s physical presence. All told, we’d only spent about a month in circumstances where we were close enough to touch one another.

This realization hit me like a brick to the head. “What the fuck WAS that, then?” I’d wonder. I thought I’d been in love, but most of the time I’d been playing a video game.

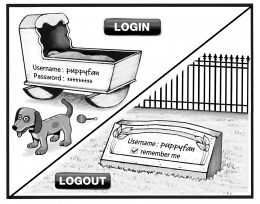

Social media has achieved what seemed impossible — we are simultaneously more connected than ever yet more isolated from one another in all the most meaningful senses.

The term “uncanny valley” is used in robotics to describe the natural waves of revulsion that roll over humans who observe a cyborg that appears to be almost entirely human but is somehow rightly perceived to be at least partially artificial. But I don’t think evolution has prepared the human brain for a situation where someone can insult you to your face but you can’t smack them in the face because the grinning face that’s insulting you is merely a simulacrum on a glass screen.

For at least a generation I’ve been publicly suspicious of people who rely too much on pop culture. If great art is supposed to accomplish anything, it’s to dole out wisdom for how to navigate and enjoy life. It’s NOT supposed to be a refuge whereby you escape life. But try telling that to some unemployed masturbator who lives in squalor while obsessing over what went wrong with the Star Wars franchise.

When the riots first hit Atlanta in June over some dusky nutmeg with a long rap sheet who resisted arrest outside a Wendy’s, snatched a cop’s Taser, and then got shot after firing the Taser at him, I noticed one Discord server comment to the tune of, “Niggas out actin’ like it’s GTA [Grand Theft Auto — it’s a video game if you’re fortunate enough to be out of that virtual-reality loop].”

And then you have BreadTube streamers like this shithead [2] claiming that some Right-wing narrative about street violence couldn’t possibly be true because he’s seen enough Marvel movies to know that people don’t act that way in real life.

So now we’re dealing with layers of nonreality — you have a new generation of “digital natives” who’ve never lived in a world without the internet and go online to interpret actual flesh-and-blood street violence through the fake lenses of video games and Hollywood movies. They don’t even know what’s real when it literally smacks them in the head. I imagine some of them, bleeding on the ground and slowly losing consciousness, thinking, “This is like that time Iron Man got attacked from behind in the second sequel. Can’t wait to post about it. . . .”

As one who places more faith in neurology to explain human behavior than I do in phantasms such as “sin” and “evil,” I did some digging on what imaging studies have concluded about the effects of being “extremely online” on the human brain. Here’s what the tests have shown thus far:

- A mere six weeks of engaging an online role-playing game “caused significant reductions in grey matter [3] within the orbitofrontal cortex — a brain region implicated in impulse control and decision making.”

- People who spend way too much time strolling amid the plastic daffodils of the uncanny digital valley “perform worse in various cognitive tasks [4] than those who do not, particularly for sustained attention.”

- “High levels of internet usage” are “associated with decreased grey matter [5] in prefrontal regions associated with maintaining goals in face of distraction.”

- A meta-analysis of 41 studies concluded that “engaging in multi‐tasking was associated with significantly poorer overall cognitive performance [6], with a moderate‐to‐large effect size.”

Among children, “higher frequency of internet use over 3 years is linked with decreased verbal intelligence at follow‐up, along with impeded maturation of both grey and white matter regions [7].”

There’s also a wealth of research suggesting that overreliance on the internet for information impedes one’s “semantic memory,” i.e., the ability to recall facts. And it makes sense — who needs a brain when you can rely on that massive electro-brain?

So spending too much time online literally causes brain damage. No wonder so many of those whippersnappers born as “digital natives” seem to have the attention span of a flea and couldn’t argue their way out of a Ziploc bag.

Excessive online use also makes people socially retarded. In a 1991 book called The Saturated Self, Kenneth Gergen warned of technology leading to a state of “multiphrenia,” which one critic [8] refers to as “a fragmented version of the self that is pulled in so many directions the individual would be lost.”

Licensed therapist Melody Bacon [8] speaks of how social media leads parents to ignore real-world dangers for their children while they seek the temporary dopamine rush of a Facebook like:

In terms of relationships, it’s just one more thing that keeps people from being able to connect and be together without fighting for attention. I know of young mothers with little kids. I see them at the park, the kids are playing or trying to get attention and Mom’s on Facebook or doing something on her phone. They think they’re engaged with the outside world but they’re not. Children are drowning with their Mom and Dad sitting there on their smartphones. They have no idea how disconnected they are.

Psychologists, whose entire job is to connect their patients to the reality of their situation, point to terms such as “depersonalization” — the sense that the self is no longer quite real — and “derealization,” the sense that the world isn’t real, either. Social media achieves both for the price of one. Psychology Today [9] quotes a student who takes online classes:

I feel like a strange copy of me is participating in a Zoom class, while another me is watching this from the side. It is like in a dream. As if I need to wake up to get myself back.

And now, with the lockdowns — which I doubt will ever end — we are all trapped in the world of nonreality [10]. I believe this is by design, and I believe its purpose is to drive us all stark raving mad. They’re going to take away everything from us except the ability to yell at one another through digital screens from the comfort of our personal padded cells.

Welcome to the Brave New Fake World.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [11] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [12].

Don’t forget to sign up [13] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.