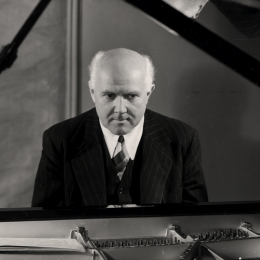

Remembering Walter Gieseking (November 5, 1895-October 26, 1956)

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledToday is the 125th anniversary of the birth of Walter Gieseking, one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. Known for his extensive repertoire, nuanced playing, and powerful memory, he was a formidable musician of rare gifts. In his later years, he attracted controversy on account of his association with National Socialism and faced attempts to stymy his career.

Gieseking was born in 1895 in Lyon, France to German parents. He had an idiosyncratic education and did not attend school until the age of 16, when he entered the Hanover Conservatory. He studied with Karl Leimer, with whom he wrote two books on piano technique (The Shortest Way to Pianistic Perfection and Rhythmics, Dynamics, Pedal and Other Problems of Piano Playing, which have been published together in a volume entitled Piano Technique). During the First World War, he served as a regimental bandsman. His career took off in the 1920s after acclaimed debut performances in London, Paris, and New York. He toured widely throughout the world until his death in 1956.

Gieseking had a prolific recording career. His discography includes the complete solo works of Mozart, Debussy, and Ravel; Beethoven’s piano concertos and sonatas; major works by Bach, Schumann, and Brahms; and many other works.

Gieseking is best known for his recordings of the works of Debussy and Ravel. His Debussy recordings, in particular, are widely considered the definitive recordings of Debussy’s piano works, and few pianists have equaled them. Gieseking’s attention to color, fine-tuned dynamic shadings, and famously nuanced pedaling made him well suited to the French Impressionists. He recorded the complete works of Debussy and Ravel for EMI in the 1950s and Columbia in the 1930s and 40s. The former sets were reissued by Warner Classics in 2015 and 2011 respectively. The sound quality falls short of modern standards, but one could argue that it adds to the atmosphere.

[2]

[2]You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [3]

It is harder to find Gieseking’s earlier recordings of Debussy and Ravel, but they are also worth listening to. The 200-CD box set Great Pianists of the 20th Century includes performances by Gieseking of Debussy, Ravel, Mozart, and Beethoven recorded in the late 1930s. Selections from his early Debussy recordings (1927-1939) have also been released under the VAI Audio label.

Gieseking was a skilled Bach interpreter and left a large body of Bach recordings. These were collected by Deutsche Grammophon in a 7-CD box set in 2017. His Mozart, reissued in an 8-CD box set by Profil Medien, is more uneven. At times his playing verges on sounding flippant, but there are also moments of luminous clarity and beauty.

Gieseking’s recordings of Rachmaninoff’s Second and Third Concertos are excellent and show that he was capable of thunderous virtuosity as well as Debussyian lightness.

There is also a great 4-CD box set released by APR that focuses on Brahms, Schubert, Schumann (with some Chopin and Scriabin). The highlight is the Brahms (opuses 76, 79, and 116–119). Gieseking’s Brahms is expressive and appropriately melancholy.

Gieseking’s recordings of Beethoven’s piano concertos are among the best. His interpretation of the Emperor Concerto is especially powerful and moving. His 1944 recording of the concerto with the Großes Berliner Rundfunkorchester under Arthur Rother, one of the earliest stereo recordings, is famous for featuring the faint sound of anti-aircraft fire outside the recording studio. Listening to this recording of German musicians performing Beethoven while being bombed by the RAF almost brings tears to the eyes.

Gieseking remained in Germany for the entirety of the Second World War. Although he never joined the NSDAP, he gave concerts for the NS-Kulturgemeinde and wanted to play for Hitler. He was placed on the Gottbegnadeten-Liste and was awarded the War Merit Cross in 1944. Horowitz alleged that he was a Nazi sympathizer, which was probably true. This charge was corroborated by Arthur Rubinstein, who reported that Gieseking described himself as a Nazi, as well as a reporter who claimed that Gieseking defended Hitler in his denazification interviews. [1] [4] Gieseking refused to respond to the accusations leveled against him by the press.

Gieseking’s attempt to resume his career after the war was met with fierce opposition. He was blacklisted in the US and was temporarily prohibited from performing. The US government subsequently cleared him and approved his US tour scheduled for January 1949, but the tour was canceled as a result of lobbying by mostly Jewish groups such as the Anti-Defamation League, the American Veterans Committee, the Jewish War Veterans, and the American Jewish Congress, as well as Arthur Klein, a US Representative from New York, who pressured the Immigration and Naturalization Service to revoke Gieseking’s visa. The INS gave in and announced its intention to stage a hearing on the subject of whether he should be deported. Gieseking left the US in disgust before the hearing could take place. [2] [5]

The Gieseking scandal is a clear-cut demonstration of the fact that, far from being an oppressed minority, Jews had a great deal of political power by the 1940s and were able to single-handedly pressure government agencies into obeying them.

Apart from the New York incident, Gieseking enjoyed a successful career after the war. He returned to the US in 1953, where he performed in a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. He continued to record large quantities of music; he was in the middle of recording a cycle of the Beethoven sonatas when he died. His reputation as one of the great masters of the piano remained intact and endures today, a doubly impressive feat given the scrutiny and opposition he faced in the aftermath of the war.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [6] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [7].

Don’t forget to sign up [8] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [9] Patrick Sherrier, “The Power of Music and the Music of Power: ‘Nazi’ Musicians in America,” senior thesis, Columbia University, 2016.

[2] [10] Ibid.