The Specter of Saint-Domingue Part I: White Genocide

Posted By Giles Corey On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled

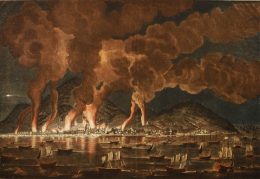

Pierre-Jean Boquet, The Burning of Cap Français, 1791.

7,803 words

The monumental significance of the fall of Saint-Domingue, the crown jewel of the French colonial empire, and its ensuant descent into the African savagery of Haiti cannot be overstated. The terrible birth of Haiti as a mangled, stillborn phoenix from a river of white blood stands as our greatest example of the infernal designs that our dispossessors hold for us: of white genocide in action. The planters of the antebellum American South carefully observed and understood its significance, and the death of white Saint-Domingue loomed large over their efforts to keep their blacks in check, just as it must inform our efforts to do the very same.

In the following discussion, we would do well to remember that the blacks of Saint-Domingue did not initiate their insurrection in a vacuum; in fact, the “Haitian Revolution” is best understood as an extension of the French Revolution, and was part and parcel thereof. Just as with the ongoing color revolution in the United States, those responsible came not from the masses, but from above. The leaders of the insurrection were the colored bourgeoisie, the privileged intermediate class between the planters and the enslaved. Many of these men had served in the French armed forces or been educated in France, and all of them had thirstily imbibed the egalitarian liqueur issuing from Paris.

By the time that the insurrection erupted in 1791, a free population of fewer than fifty thousand whites exercised a tenuous dominion over half a million blacks; at the time, of course, most of the planters of Saint-Domingue had only a dim perception that they sat atop such a roiling volcano. [1] [1] The whites certainly entertained no illusions about the native ferocity of their blacks, however, for “the base of slave societies is fear. . . For, if the slave feared the master, the master also feared the slave. In the background of San Domingan life, there lowered a dark shadow, of which men thought much even when they spoke little.” [2] [2] Since 1679, there had been numerous insurrectionary conspiracies of varying levels of success.

The most disturbing of such occurred around 1750, when Makandal, claiming to be “the Black Messiah,” amassed a formidable following. His “army” planned to poison the water supply and exterminate the whites while they were “in convulsions.” The conspiracy was discovered in the nick of time and its leader was executed, “yet even in death he left behind a legacy of unrest. . . the colony was never free from poisonings and disturbances.” In 1785, one royal officer wrote that “we are walking on barrels of powder,” echoing the words of a royal governor one century prior: “We have in the negroes most dangerous enemies.” Soon, “sparks from the edicts of Revolutionary France were soon to fall upon those powder-barrels.” [3] [3]

Upon the outbreak of the French Revolution, Saint-Domingue almost immediately experienced a sharp uptick in servile unrest. One royal officer, in a report forwarded to the Minister of Marine, wrote: “Sir, this word ‘Liberty,’ which is echoing so loudly all the way from distant Europe to these parts, and which is being everywhere repeated with such enthusiasm, is sowing a fatal seed, whose sprouting will be terrible. . . we should see only blood, carnage, and the certain destruction of one or other of those incompatible races of men which inhabit this colony.” It seemed indeed that “the gods had. . . decreed the destruction of San Domingo.” [4] [4]

On the eve of the insurrection, France had in Saint-Domingue “the finest colony in the world. Her historians are never weary of enumerating the amount of its products, the great trade, the warehouses full of sugar, cotton, coffee, indigo, and cocoa; its plains covered with splendid estates, its hill-sides dotted with noble houses; a white population, rich, refined, enjoying life as only a luxurious colonial society can enjoy it.” When the Constituent Assembly in Paris decreed in May, 1791, that “every man of colour born of free parents should enjoy equal political rights with the whites,” the planters quite presciently predicted that this would foment civil war and the loss of the colony. In response, Dupont de Nemours and Maximilien Robespierre replied, “Perish the colonies rather than a principle.” [5] [5] In the words of Mirabeau, the whites “slept on the edge of Vesuvius.” [6] [6]

On August 22, 1791, the death knell tolled for the white race in Saint-Domingue. Though the full detail of its origins will forever be shrouded in mystery, the attack that was then launched across the island’s North Plain was well-coordinated and systematically executed. The scattered, isolated whites of the plain could offer no resistance as the men were ruthlessly slaughtered “with every species of atrocity” and the women brutally raped, often upon the very bodies of their husbands, fathers, brothers, and children. Just before dawn on August 23, a stream of disheveled refugees filtered into Le Cap, awash in the lurid glow of the flaming plain, carrying reports of the massacre and the news that the blacks were razing the cane fields and the plantations. [7] [7] A colonist described the sight of the white refugees:

I beheld the wide expanse of [the] road literally crowded with a disheartened multitude. I felt overpowered with irresistible emotions; my heart swelled as if ready to burst. What a heart-rending scene! Countless numbers of females. . . old and young, dragging along, as it were, their weary bodies — some carrying their babes and children, others measuring their steps to avoid precipitating the tardy steps of their grandmothers and grandfathers — many of whom were more than seventy years old! Exhausted by a meridian heat, by thirst and hunger, they had in their flight thrown down along the road all the articles which they thought would impede or retard their march. [8] [8]

One of the first whites to have experienced the chaos on the plain — and one of the few survivors to live to tell the tale — awoke to the sound of gunfire. Within seconds, his land was inundated with the horde of blacks. He shouted, “Who goes there?” A voice “like thunder” answered: “It is death!” The savages were rhythmically chanting, “Kill, kill.” The man, despite his understandable terror, made the striking observation that “truly, the apathy and reluctance of these animals was such that if only ten whites had arrived at the moment, they would have broken up this savage horde with no resistance.” [9] [9] One woman, resting on her veranda, was awakened by her husband’s severed head being tossed into her lap. In flight, she paused to view her reflection in a stream. Her hair, “which was brown a few days before, had become completely white.” [10] [10] Another eyewitness on the North Plain described the terror thus:

The day after my arrival, while partaking with my family of the pleasures of an excellent lunch, a courier arrived to deliver to my step-father, commander of the district in which our property is located, a letter full of the most terrifying news. The slaves, enflamed by emissaries sent from France, had burned the habitations of our neighbors near [Le Cap], after assassinating the proprietors without distinction of age and sex. . . [We] feared it would soon reach our place of habitation. The report of this terrific catastrophe was widely spread. The frightened families among our neighbors met together at our plantation. The men armed to face the storm; the mothers, wives, sisters were lamenting and gathering in all haste a few precious effects. Desolation and fear were painted on all faces. The sky seemed on fire. Guns could be heard from afar, and the bells of the plantations were sounding the alarm. The danger increased. The flames at each moment were approaching and enclosing about us. There was no time to lose; we fled. . . . The victims who escaped at sword’s point came to swell the number of fugitives, and recounted to us the horrors which they had witnessed. They had seen unbelievable tortures to which they testified. Many women, young, beautiful, and virtuous, perished beneath the infamous caresses of the brigands, amongst the cadavers of their fathers and husbands. Bodies, still palpitating, were dragged through the roads with atrocious acclamations. Young children transfixed upon the points of bayonets were the bleeding flags which followed the troop of cannibals. These pictures were not exaggerated, and I more than once saw the sorrowful spectacle. [11] [11]

“We were crushed,” the Frenchman continued, with hundreds of thousands of blacks in open revolt against whites defended only by two regiments of regular soldiers, along with the colonial militia. One crippled black was enough to reduce a man’s fortune to cinders. The colonist was, however, encouraged by his observation that “it was only in ambuscades that our adversary was formidable; in open country, one single white could put to rout twenty of these poor wretches, no matter how well-armed.” [12] [12] Coming upon the ruins of his own plantation, and thus his livelihood and his economic existence, the colonist wrote:

My sister, it is done; our ruin is consummated; I saw the turbulent flames, which were carried by the breeze in its course; I gazed upon the debris; I walked over the ashes still hot and red! . . . What days, perhaps, with still worse to follow! . . . How you would have suffered if you could have seen the actual state of this place which, before our arrival, so much care was taken to develop: the sugar refinery; the vats, the furnaces, the vast warehouses, the convenient hospital, the water-mill which was so expensive, all is no more than a specter of walls blackened and crumbled surrounded by enormous heaps of coals and broken tiles. . . All the materials assembled at great expense for the construction of the beautiful new house we were going to build, were scattered or broken; and they did their work with great thoroughness. They demolished the aqueduct which conducted the river water to the great wheel of the mill; and they drained the pond by numerous irrigation trenches, that picturesque lake which carried such coolness to the habitation, and which always furnished such delicious fish. Why such fury in the devastation? Why deprive themselves of that which might have been so useful to them one day? It could not be out of hatred for us personally — we were complete strangers. [13] [13]

Though the full horror of the situation was soon impressed upon the people of Le Cap, the cataclysmic intensity of the bloodshed could not have been appreciated then. The unerring success with which the French authorities had suppressed every other insurrectionary conspiracy had made the whites overconfident. A reconnaissance party of National Guardsmen ventured out of the city, but had barely entered the plain when it was “suddenly overwhelmed in the half-light of dawn by a horde of negroes whose ghastly standard was the impaled body of a white child; only two or three of the soldiers escaped to carry the dreadful tidings. Within a few days, the whole of the great North Plain was to be only a waste of blood and ashes.” The whites of Saint-Domingue were paralyzed. [14] [14] An eyewitness described the plain:

Picture to yourself the whole horizon a wall of fire, from which continually rose thick vortices of smoke, whose huge black volumes could be likened only to those frightful storm-clouds which roll onwards charged with thunder and with lightnings. The rifts in these clouds disclosed flames as great in volume which rose darting and flashing to the very sky. Such was their voracity that for three weeks we could barely distinguish between day and night, for so long as the rebels found anything to feed the flames, they never ceased to burn, resolved as they were to leave not a cane nor house behind. The most striking feature of this terrible spectacle was a rain of fire composed of burning cane-straw which whirled thickly before the blast like flakes of snow, and which the wind carried. . . plunging us in the greatest fear of its effects and wringing our hearts with an agony of grief as it disclosed the full extent of our misfortunes. [15] [15]

Another French colonist wrote even more evocatively of the spectacular inferno, a glimpse directly into the fires of Hell:

I beheld the most awful and desolating spectacle: no less than ten square leagues of country illuminated by thousands of volcanoes. I stood gazing in despair two hours, upon this beautiful scene, to observe the progress of the conflagration eastward. Its rapidity was such as to make the beholder believe that large and thick trains of gunpowder had. . . been artificially laid down, leading from. . . each estate to the neighboring ones; as in a large and splendid artificial fireworks, by letting off a fire dragon [that] communicates its destructive element, enflames by turns several parts of the vast combinations, lets off thousands of thundering rockets, and after exhibiting a sea of fire, leaves behind but the blackened wrecks of his former grandeur, when, suddenly rekindling, it continues its tremendous blasts forwards, until it dies away for lack of combustible elements. [16] [16]

Another eyewitness, arriving at Le Cap a month later, noted that “the first sight which arrested our attention as we approached was a dreadful scene of devastation by fire. The noble plain adjoining Le Cap was covered with ashes, and the surrounding hills, as far as the eye could reach, everywhere presented to us ruins still smoking, and houses and plantations at that moment in flames. It was a sight more terrible than the mind of any man unaccustomed to such a scene can easily conceive.” [17] [17] One woman described the once-gleaming town “a heap of ruins. A more terrible picture of desolation cannot be imagined. Passing through streets choked with rubbish, we reached with difficulty a house which had escaped the general fate. The people live in tents, or make a kind of shelter, by laying a few boards across the half-consumed beams.” [18] [18] The colonial journalist H. D. de Saint-Maurice described the city in similar terms:

Oh, you who, in the lap of luxury, enjoy peaceful days free from problems, cast your gaze for a moment on two or three thousand individuals, most of whom enjoyed, only two days ago, a brilliant fortune, lavish and comfortable homes, and everything that makes life enjoyable. See these unfortunates now, without bread and without assistance. . . See here a mother who bemoans the fate of her lost children, a father mourning a son who is dead or dangerously wounded, and there a beautiful young woman, trembling, seated next to a hedge or a house occupied by one who used to be her slave. Alone and friendless, she doesn’t know what happened to her family and fears suffering at any moment the final outrage and being given over to the brutality of a slave whose hands will be covered with the blood of her mother, her brother, perhaps even her lover! See all these unfortunates exposed night and day to the insults of their ferocious conquerors and the rigors of the climate. [19] [19]

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [20]

Within the first two months of the insurrection, well over two thousand whites had been exterminated, another thousand had been “reduced from opulence to abject destitution,” and over a thousand sugar, coffee, cotton, and indigo plantations had been erased as if they had never existed. As one colonist wrote: “To detail the various conflicts, skirmishes, massacres, and other scenes of slaughter which this exterminating war produced, were to offer a disgusting and frightful picture; a combination of horrors wherein we should behold cruelties unexampled in the annals of mankind; human blood poured forth in torrents, the earth blackened with ashes, the air tainted with pestilence.” [20] [21] No small quantity of whites committed suicide rather than face being ripped limb from limb, raped, and eviscerated by subhuman monsters. [21] [22]

As the North Plain was rent asunder, a mulatto insurrection consumed the West, centered upon Port-au-Prince. They “fashioned white cockades from the ears of their dead enemies,” and committed grotesque atrocities against white women and children which were “beyond belief.” The Colonial Assembly reported to its unsympathetic Parisian commissioners that “the mulattoes rip open pregnant women, and then before death force the husbands to eat of this horrible fruit. Other infants are thrown to the hogs.” [22] [23] Some whites were “placed between planks and sawn in two, or were skinned alive and slowly roasted, the girls violated and then murdered,” while others had their eyes ripped out with corkscrews. [23] [24]

A Monsieur Le Clerc, who in November 1791 joined one of the early expeditions undertaken against the black insurgency, described what he saw: “Ruins, ashes, scaffolds stained with blood, trees hung with heads that were already putrefying: that is the tableau of this, the most opulent province of the colony. . . The rich parishes. . . now echo only with the cries of these wild beasts who carry out their ravages there.” The blacks, “instead of just killing the animals they needed for food, ran around, sabers in hand, amusing themselves by cutting sheep and pigs in half and using only a small part, with the result that the stench that soon began to rise from this infected place. . . forced us to flee it.” Mutilated corpses attested to more than sheer rage — cannibalism was apparently rampant among the “revolutionaries.” [24] [25] He continued:

From a distance, it looked like universal desolation. Our ruin was complete. One person hardly recognized the site of his own plantation, the other the plantation of a friend he sought in vain. What the fire had spared, hands even more destructive than the flames had reduced to dust. We felt as though we were marching on the ruins of the world. Sad playthings of fate, the plantation owners mixed in with the main body of the army dragged themselves along, lost in contemplation of their misery. . . no animal, no living creature interrupted the silence of these deserts, broken only by the rumbling of the cannon and the slow and measured pace of the troops. . . . Oh, what an abomination! Oh, inventive genius of cannibals! What did we see? White hands, from the wrist up, coming out of the ground, with the fingers pointing upward. We stood petrified. Did they belong to bodies buried here? Had parricidal hands torn them from living victims, these hands that I must have held in my own? Ah! No doubt they belonged to a father, a friend, a mother. They might just have signed the manumissions of some of these monsters. . . who had made killing a game. These whites had been torn apart! . . . Their suffering was over. . . Their shades hovered over our heads. . . . As I moved away from this theater of horror, the tempest howled through my very being, deeply, like a roaring torrent, something that shakes the fundament of things. At moments, full of rage, I formed only one vow: to measure myself against one of these man-eaters, and. . . to run the iron through his innards. At other moments, exhausted by the very violence of my sensations, I wished that a friendly bullet would pierce me, but that it would reach me slowly, so that. . . I could fully savor the end of such an existence. [25] [26]

The men liberated a group of white women who had been held captive in a sacked church and subjected to several days of uninterrupted gang-rapes: “O heaven! What a spectacle! Livid women, starved, without stockings, without shoes, their hair undone, most almost naked, a few covered with rags, others with nothing but a scrap to cover their nudity: specters, in a word.” Nearby the church lay a heaping pile of the skulls of white victims, the bone covered here and there with patches of blood-matted hair and rotten flesh. Curiously, one “little old woman,” who had been Mr. Le Clerc’s neighbor, had actually refused to lay with the blacks and had not been raped, but instead given fifty lashes, “whose scars she still bore.” [26] [27]

One Monsieur Gros, an attorney who also volunteered in an early militia expedition against the blacks, was one of the only survivors after he and his unit were captured by the monstrous “Jeannot,” one of the most bloodthirsty of the nascent Haitians, known for his orgiastic passion for torture and his penchant for drinking the blood of his white victims, mixed with rum. [27] [28] The blacks “glutted themselves by shocking our eyes with the mutilated carcasses of our brethren.” Some men were butchered piecemeal, while others were trussed, “like a fowl ready-prepared for the spit, toad-fashion,” and roasted alive or exsanguinated, their blood drunk by their tormentors. A companion of Mr. Gros was “extended on a ladder” and given three hundred stripes, after which gunpowder was “inserted into every part of his body and exploded by the application of red-hot pokers fabricated expressly for this intent.” [28] [29]

It was the unit commander Berchais, however, who was doomed to the grisliest death. “Jeannot” severed one of his hands, extended him upon the ladder, whipped him two hundred times, and finally “suspended [him] from a stake fixed in the ground by a hook that pierced him under the chin. This unfortunate man [lived] in this condition 36 hours, and at the time [Jeannot] had him taken down, he still palpitated.” It was no easy task cutting Berchais’s corpse down: “They had to cut off his head because the hook under his jaw had gone in so deeply, and he was still warm.” “Jeannot” had not been lying when he told his victim: “You are going to feel that death.” [29] [30]

Le Cap, the largest city in Saint-Domingue, was completely incinerated twice in ten years. Walking through its once-bustling avenues, one man wrote that he “found nothing but dead bodies: the streets were strewn with them, all the houses were burned and the streets blocked by their debris.” [30] [31] Le Cap, “with its modern European-style buildings, including a theater, had been a symbol of the implantation of Enlightenment culture in the New World. Its destruction was the most striking act of violence committed on French territory since the start of the revolution.” [31] [32] As annihilation loomed ever-nearer on the horizon, the whites did their best to flee the colony. One observer describes what occurred upon the arrival of a French fleet:

Christophe, the black general. . . rode through the town, ordering all the women to leave their houses — the men had been taken to the plain the day before, for he was going to set fire to the place, which he did with his own hand. The ladies, bearing their children in their arms, or supporting the trembling steps of their aged mothers, ascended in crowds the mountain which rises behind the town. Climbing over rocks covered with brambles, where no path had been ever beat, their feet were torn to pieces and their steps marked with blood. Here they suffered all the pains of hunger and thirst; the most terrible apprehensions for their fathers, husbands, brothers and sons; to which was added the sight of the town in flames: and even these horrors were increased by the explosion of the powder magazine. Large masses of rock were detached by the shock, which, rolling down the sides of the mountain, many of these hapless fugitives were killed. [32] [33]

In a scene captured by the journalist H.D. de Saint-Maurice, white refugees who managed to escape aboard ships watched from the harbor as their world spun away from them:

In the midst of this profound darkness, everyone, silent and frozen with horror, had contemplated from the decks of the ships in the harbor the torrents of flame that devoured this once opulent and peaceful city, become in an instant the prey of pillage and fire. Daylight, in dissipating the darkness, offered the hideous image of civil war and ruins; only then was the impossibility of going back on land evident. Rear Admiral Sercey, seeing the immense crowd of people who had taken refuge on the ships, and realizing, no doubt, the impossibility of saving any more, ordered preparations for departure. . .the signal is given and repeated, it resounds like a thunderclap in the hearts of these innumerable victims. It is the cry of despair, the last, the eternal farewell to the homeland. Everyone wants to stop the vessel that flees with too much speed, everyone wants to touch for one last time, to at least moisten with his tears, the soil on which he was born, the soil that made him rich, this beloved and sacred soil that he tears himself away from so painfully. The man weeps for his missing wife, the wife cries out for the husband from whom she is separated, fathers and mothers seek their children who, far from them, invoke the protection of their parents. Some stretch out empty arms to their friends, to beloved mistresses whom they may never see again; their voices, their farewells are lost in the atmosphere. [33] [34]

A volunteer militiaman witnessed the spectacular death of the city, which had so recently been world-renowned as “a little Paris in terms of grandeur and beauty.” He saw one of his generals, consumed by fright and despair, throw himself into the sea, crying, “Every man for himself!” He saw colored troops “proudly leading us and haranguing us into excitement, who, when they had accompanied us as far as the batteries of the enemy, turned upon us a murderous fire and retired amidst the ranks of our adversaries, laughing at our credulity.” [34] [35] He continued:

The creeping hours were hardly half run out when, all at once, horrible shrieks resounded in our ears; a great brightness lit the black skies. From the summit of the mountains down the roads to the plain, came immense hordes of Africans. They arrived with torches and knives and plunged into the city. From all sides, flames were lifted as in a whirlwind and spread everywhere. What a spectacle of cruelty! I can still hear the whistling of bullets, the explosions of powder, the crumbling of houses; I can still see my brave comrades contending vainly against steel and fire; I still see the feeble inhabitants in flight, half-naked, dragging in the streets, in the midst of accumulated debris, the mutilated corpses of their families or their friends. . . The entire city was entirely ablaze. . . Once a flourishing city, now reduced to ashes. These heinous Africans, all stained with blood, were replacing murder with excesses, amidst a population without refuge, without clothes, and without food. The thousands of unfortunates of different sex and ages were sitting on the ruins of their property crying for the loss of their families and their friends. The shore was covered with debris, with weapons, with wounded, with dead and with dying. On one side, a barrier of flames and of swords; on the other, the immense expanse of ocean. Over all was misery, want, and suffering! And nowhere was there hope! [35] [36]

Nowhere, indeed, was hope to be found. One French official sent a desperate missive to the motherland, imploring his superiors for military aid: “If the Directoire does not promptly send imposing forces, the colony is lost forever. . . the Europeans are everywhere being massacred. The cantons. . . are completely devastated, and outside of the town itself not a White man remains alive. . . we are at the mercy of the negroes. . . by the time you receive this letter, we may have all been massacred.” [36] [37] The arrival of revolutionary French forces with Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité on their lips scarcely helped the whites, and actually served to worsen the chaos. British and Spanish forces eventually invaded the island in an attempt to reassert white control, but their respective interests were the same: imperial power games, rather than white supremacy.

The report of one Frenchman is exemplary of this tragic white disunity. He had managed to escape to the United States in 1793, but returned to Saint-Domingue the following year to rejoin the fight for white rule. Because France had declared emancipation, diehard white colonists were forced to join either the British or the Spanish. The narrator was present, and thus barely escaped with his life, at the Fort Dauphin massacre, in which Spanish troops stood by while whites were massacred by blacks serving under “Jean François,” a black commander then loyal to the Spaniards. Spain had invited the French colonists to return, only to corral them at Fort Dauphin, disarm them, and leave them to the invidious mercy of the blacks. When the slaughter commenced, the Spaniards refused to intervene, literally standing by as their racial kinsmen were destroyed. They refused to give the narrator a weapon, or even to grant him the mercy of a sudden death. [37] [38] He escaped the onslaught by the skin of his teeth, and happened upon a white girl surrounded by the horde:

The beasts began by tearing off the jewels which she had on her person; then they betook themselves to satisfy their brutal lust. . . I could see her lying amidst the human debris, pale, immobile. I could see the excited Africans, disputing the right for the first ebony embrace of her tender beauty. The monsters! Their desire resembled rage, what with their glistening teeth and wild expressions. . . She had more need of consolation than I. I saw her still stained with the blood of her husband, whom they slaughtered in her arms, and her ears were still bleeding from having their ornaments torn from them. She was indeed to be pitied! Hardly sixteen, sweet and lovely, she was without succor among monsters who respected nothing. Besides having lost her friends, as I had, she had the sorrow of losing that one whom her heart had chosen to be the companion of her happiness and sorrow, and whom she had seen taken by a dreadful and premature death. . . I saw desolate women, half-naked images of terror and despair. Some carried the tender fruit soon to be born, only to grieve always for a lost father. Some presented in vain to their nurslings breasts that were dried up from 24 hours of fasting and anxiety. I saw men covered with wounds imploring vainly for help. [38] [39]

The horror continued for years, events in fallen Saint-Domingue mirroring the convulsions of France. The whites who still remained in the colony knew that there was only one practical solution to the chaos, the same solution for which the European powers had lacked the requisite will to perform since the very beginning of the descent into barbarism:

Almost all the negroes in the gendarmerie have deserted bag and baggage to the enemy, and the same thing is true of the black troops. After such examples, how can we trust those negroes who appear to desire submission? So long as there remains at San Domingo any considerable body of negroes who for twelve years have made war, the colony will never be reestablished. The negro who has been a soldier will never again become a cultivator; he prefers death to work. He who has once worn an epaulette holds it dearer than life; he will commit every crime to retain it. If France wishes to regain San Domingo, she must send hither twenty-five thousand men in a body, declare the negroes [to be] slaves, and destroy at least thirty thousand negroes and negresses — the latter being more cruel than the men. These measures are frightful, but necessary. We must take them or renounce the colony. Whoever says otherwise lies in his throat and deceives France. [39] [40]

Alas, the necessary action was never taken. In fact, quite the opposite. Eventually, after the arrest and subsequent death of “Toussaint Louverture,” one of his most vicious lieutenants, “Dessalines,” took power. This beast developed a reputation early on for his propensity for drinking his white victims’ blood. [40] [41] In 1802, under two years before the final extermination of the white race from the island was set into motion, a French expeditionary force effected another attempt at reasserting control. Michel-Etienne Descourtilz was among this army, and wrote of his experiences after he and his unit were captured by blacks under Dessalines’s command:

From all directions, the noise of firearms woke those whom anguish had exhausted. Everyone strained to hear, to not miss the last plaintive cries of the victims dying under the redoubled blows of the assassins, either bayoneted or clubbed with musket butts. . . Death by shooting being too merciful to satisfy these cannibals’ cruel rage, they reserved it for those who had been promised special treatment. The whites of the canton. . . were soon pursued and collected from all over. Their brains, flying in all directions, stuck to the blood-spattered walls. . .homicidal lead flew in all directions; the perfidious balls struck old people and children without distinction. . .Everywhere scattered ashes, twitching corpses marked the assassins’ passage and their bloody march. . .The streets were strewn with bodies. . . During this time, the holy cathedral was desecrated, the altar soaked with the blood of a young man of sixteen, who, his hair disheveled, came on his knees to beg for divine protection, his hands and mouth dripping blood, naked; in spite of the sanctity of the place, the cannibals finished off this innocent victim who had survived more than forty bayonet thrusts! . . . Having no pity for the white soldiers who, lost in the woods and overwhelmed with fatigue, though that, if they laid down their arms, they would find protection and life, they led them to the chiefs of the bands, striking them brutally. . . atrocious methods of putting them to death were prepared. For example, after having cut off the hands and feet of some, and attached ropes to their limbs, they were hung eight feet off [of] the ground by large splinters of wood driven through their lower jaws, and then abandoned, leaving it to time alone to torture them more slowly. Exposed thus during the day to the heat of a burning and insupportable sun, in the evening and the night to the indescribable discomfort of innumerable legions of insects and mosquitoes attracted by the blood with which these victims were covered, they never lasted more than thirty to forty hours. [41] [42]

He continued, attesting to the remarkable ubiquity of animal cruelty among the blacks:

With a heavy heart, I abandoned this bloodstained terrain, which now held so many beloved remains, and I turned my eyes, full of sadness, toward the mountains. To the human bodies were added those of domestic animals sacrificed by the drunken ferocity of these barbarians, who had also killed a vast quantity of poultry, without any purpose. These ferocious [savages] pushed their cruelty to the point of cutting a single rib out of the cattle, for grilling, and afterward they let the animal go! [42] [43]

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [44]

When the expeditionary force abandoned the colony in November, 1803, Dessalines promised that any whites who chose to stay would do so under his personal guarantee of protection, and even went so far as to invite white refugees to return to the land that they had so loved. Scarcely had the new year begun, however, when these poor, naïve whites discovered just how wrong they had been. Dessalines issued a proclamation officially ordering the wholesale annihilation of the white race, setting off numerous waves of horrific massacres. [43] [45] A French officer who escaped certain death at Port-au-Prince wrote:

The murder of the Whites in detail began at Port-au-Prince in the first days of January, but. . . [in] March they were finished off en masse. All, without exception, have been massacred, down to the very women and children. . . [They] ranged the town like a madman searching the houses to kill the little children. Many of the men and women were hewn down by sappers, who hacked off their arms and smashed in their chests. Some were poniarded, others mutilated, others ‘passed on the bayonet,’ others disemboweled with knives or sabers, still others stuck like pigs. At the beginning, a great number were drowned. The same general massacre has taken place all over the colony, and as I write you these lines, I believe that there are not twenty Whites still alive — and these not for long. [44] [46]

Apparently, the author of Dessalines’s portentous proclamation was himself white, and became the first sacrifice. A witness described the scene of one of the multitude of bloodbaths:

The destined victims were assembled in a public square, where they were slaughtered by the negroes with the most unexampled cruelty. One brave man, who had often distinguished himself in the defense of the Cape, and who had been weak enough to stay in it, seized with desperate fury the sword of one of the negroes, and killing several, at length fell, overpowered by numbers. . . The women have not yet been killed; but they are exposed to every kind of insult, are driven from their houses, imprisoned, sent to work on the public roads; in fine, nothing can be imagined more dreadful than their situation. Two amiable girls, whom I knew, hung to the neck of their father when the negroes seized him. They wept and entreated these monsters to spare him; but he was torn rudely from their arms. The youngest, attempting to follow him, received a blow on the head with a musket which laid her lifeless on the ground. The eldest, frantic with terror, clung to her father, when a ruthless negro pierced her with his bayonet, and she fell dead at his feet. The hapless father gave thanks to God that his unfortunate children had perished before him, and had not been exposed to lingering suffering’s and a more dreadful fate. [45] [47]

She continued:

Armed negroes entered the houses and drove the inhabitants into the streets. The men were led to prison, the women were loaded with chains. . . The unfortunate madame G——, chained to her eldest daughter, and the two youngest chained together, thus toiled, exposed to the sun, from earliest dawn to setting day, followed by negroes who, on the least appearance of faintness, drove them forward with whips. A fortnight later the general massacre took place, but the four hopeless beings of whom I particularly write, were not led to the field of slaughter. They were kept closely guarded, without knowing for what fate they were reserved, expecting every moment to hear their final sentence. They were sitting one day in mournful silence, when the door of their prison opened, and the chief, whose letter had induced them to stay, appeared. He saluted madame G—— with great familiarity, told her it was to his orders she owed her life, and said he would continue his friendship and protection if she would give him her eldest daughter in marriage. The wretched mother caught the terrified Adelaide, who sunk fainting into her arms. The menacing looks of the negro became more horrible. He advanced to seize the trembling girl. “Touch her not,” cried the frantic mother; “death will be preferable to such protection.” Turning coldly from her he said, “You shall have your choice.” A few minutes after a guard seized the mother and the two youngest daughters and carried them out, leaving the eldest insensible on the floor. They were borne to a gallows which had been erected before their prison, and immediately hanged. Adelaide was then carried to the house of the treacherous chief, who informed her of the fate of her mother, and asked her if she would consent to become his wife? “[A]h! no,” she replied, “let me follow my mother.” A fate more dreadful awaited her. The monster gave her to his guard, who hung her by the throat on an iron hook in the market place, where the lovely, innocent, unfortunate victim slowly expired. [46] [48]

Under Dessalines, the horror became as grotesque as it had been in the first days of the revolution. One account reported: “A passage boat. . . with 44 souls on board, was taken by one of those [negro] barges, and every soul murdered. The women they put to the ignominious torture of boring out their eyes with a corkscrew, in ripping up the bellies of those with child, and exposing the unborn infants to the eyes of their expiring mothers.” [47] [49] Of course, Dessalines managed to destroy more than the white “devil.” With the death of the whites, so too died “technical expertise, commercial connections, and any semblance of a productive economy” — in other words, Dessalines butchered any hope of future prosperity. [48] [50]

Peter Chazotte, one of the very few French whites who survived the final months of Saint-Domingue’s death throes, provided the fullest account of Dessalines’s proclamation. Mr. Chazotte had fled the colony for the United States in the 1790s, but returned in 1800 in a likely futile effort to recover his property. By the grace of God, he was able to make it to Baltimore in June, 1804. The Frenchman blamed British abolitionists for the entire series of events, convinced that agents associated with William Wilberforce had launched their campaign in 1789 and had explicitly recommended to Dessalines his policy of white genocide.

Though Mr. Chazotte wrote his memoirs in French at the behest of the French Ambassador to the United States, the diplomat took umbrage at the refugee’s harsh judgments on French military failures, and Chazotte left his manuscript unpublished. In 1840, however, he decided to publish it in English in order to answer “the obstreperous misrepresentations of English abolition agents” and to counter “the nefarious lies propagated by American fanatics” of the Northern abolitionist cabal. He believed that the British were conspiring to promote abolitionism in the United States in the hope of ruining a commercial rival. He well understood that “they only await. . . a signal to kindle the conflagration, and make of our Southern section a vast field of war, destruction, misery, rapine, murder, carnage and blood.” [49] [51]

On March 8, 1804, Dessalines issued the fateful proclamation: “By order of the Governor-General of the Island of St. Domingo: all white male inhabitants of whatever nation or country they may be natives, are commanded to appear tomorrow, the 9th of March, at eight in the morning, at the Place of Arms, for the Government to take a census of their number. At nine o’clock, domiciliary visits shall be made by armed patrols, throughout the town, and every white man found concealed in any place, shall instantly be put to death in front of the place of his concealment.” [50] [52]

Nearly 1,500 white men were then forcibly death-marched to their doom: “Their number increased as they went on. When they passed by my door, they numbered about three hundred, most of them old men, with grey and white locks hanging down upon their shoulders; some were so weak as to be almost unable to move their legs forward, and were supported as they walked by their friends.” [51] [53] Mr. Chazotte continued:

It was. . . in the silence of the night, when four hundred wretched innocent white men who, on this afternoon, had given up all they possessed to save their lives, now stripped of all their clothes, their arms fastened behind their backs, and tied two by two with cords. . . were seen dragged along. . . They made a halt in front of Dessalines’s headquarters for him to behold the white victims, offered as a sacrifice to propitiate the promised favors of his sanguinary god, Wilberforce. . . I heard the piercing cries of despair, the lamentations, the agonies of death, and the harsh rebukes and vociferations of the soldiery. Then I heard a voice ordering them off. . . . They began by placing their heads upon blocks of wood, and they decapitated them with. . . axes; but, this requiring too much time, the regiment fell upon them with the bayonets and swords; none escaped. . . their bodies were thrown one above the other, so as to form a mound of dead bodies, for the country negroes, as Dessalines said, to look at their masters and no longer depend on them. [52] [54]

One woman begged for her husband’s life, offering her body as an inducement. After the blacks had ravaged her, they proceeded to string up and butcher her husband. Mr. Chazotte witnessed hundreds of white men being dragged, naked, “forcibly on the rough stones, by soldiers, lighted by innumerable torches. . . They stopped in front of Dessalines’s quarter. . . I hid my eyes with my hands. I looked again; I saw the blood gushing out of the inflicted wounds. I could see no longer; I fainted and fell.” [53] [55]

Dessalines was no hypocrite; fearing that some of his men would not employ the requisite fever-pitch of cruelty, the black leader personally toured the countryside and “pitilessly massacred every French man, woman, or child that fell in his way. One can imagine the saturnalia of these liberated slaves enjoying the luxury of shedding the blood of those in whose presence they had formerly trembled; and this without danger; for what resistance could those helpless men, women, and children offer to their savage executioners?” [54] [56]

Mr. Chazotte had the fleeting opportunity to speak with Dessalines’s secretary in the following days, and the secretary spoke of what he had seen while accompanying Dessalines on an excursion to survey the fruits of his proclamation: “When they entered the prisons, they viewed many corpses, besmeared with gore; in every apartment, the floor was, two inches deep, encrusted with coagulated blood; the walls were dark, crimsoned with the gushes of human blood. Having viewed this slaughterhouse of human bodies,” they traveled to the scene of another massacre outside the city, “where upwards of four hundred bodies lay heaped on one another in two high mounds. The blood flowing from beneath had. . . formed a bar of coagulated blood forty feet wide.” [55] [57]

White Saint-Domingue was dead, eviscerated by the black Haitian bastard that sprung from its distended stomach.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [58] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [59].

Don’t forget to sign up [60] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [61] Stewart R. King, “Slavery and the Haitian Revolution,” The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, Paquette and Smith, eds. (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 600, 603.

[2] [62] T. Lothrop Stoddard, The French Revolution in San Domingo (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), p. 62.

[3] [63] Ibid., 65-67.

[4] [64] Ibid., 94-95, 99.

[5] [65] Sir Spenser St. John, Hayti, or the Black Republic (London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1884): 30, 36.

[6] [66] Stoddard, 130.

[7] [67] Ibid., 128, 130-31.

[8] [68] Jeremy D. Popkin, Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection (The University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 344.

[9] [69] Ibid., 50, 52.

[10] [70] Alfred N. Hunt, Haiti’s Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), p. 41.

[11] [71] Popkin, 73-74.

[12] [72] Ibid., 77, 79.

[13] [73] Ibid., 87-88.

[14] [74] Stoddard, 130-31.

[15] [75] Ibid., 131-32.

[16] [76] Popkin, 342.

[17] [77] Stoddard, 132.

[18] [78] Leonora Sansay, Secret History; or, the Horrors of St. Domingo (New York: Bradford & Inskeep, 1808), L-I.

[19] [79] Popkin, 199.

[20] [80] Stoddard, 135.

[21] [81] Hunt, 41.

[22] [82] Stoddard, 151.

[23] [83] St. John, 39; Popkin, 90.

[24] [84] Popkin, 96-97.

[25] [85] Ibid., 97-98.

[26] [86] Ibid., 99-101.

[27] [87] St. John, 47.

[28] [88] Popkin, 123, 125-27.

[29] [89] Ibid., 108, 127.

[30] [90] Ibid., 221.

[31] [91] Ibid., 181.

[32] [92] Sansay, L-I.

[33] [93] Popkin, 202.

[34] [94] Ibid., 212, 222.

[35] [95] Ibid., 213-14.

[36] [96] Stoddard, 261.

[37] [97] Popkin, 257.

[38] [98] Ibid., 258, 261.

[39] [99] Stoddard, 346-37.

[40] [100] Ibid., 291.

[41] [101] Popkin, 289, 291, 301.

[42] [102] Ibid., 276-77, 293.

[43] [103] Stoddard, 349.

[44] [64] Ibid., 349-50.

[45] [104] Sansay, L-XXI.

[46] [105] Ibid., L-XXII.

[47] [106] Hunt, 38-39.

[48] [107] Ibid., 39-40.

[49] [108] Popkin, 337-39.

[50] [109] Ibid., 345-46.

[51] [110] Ibid., 347, 349.

[52] [111] Ibid., 353.

[53] [112] Ibid., 354, 356-57.

[54] [113] St. John, 75.

[55] [114] Popkin, 358-59.