Music & Meaning in Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 1,985 words

1,985 words

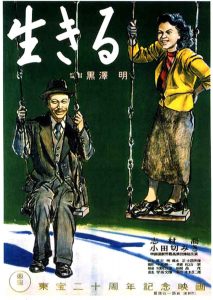

It would be easy to make Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 masterpiece Ikiru into something trite and hopeful — like an existential affirmation of life. But that wouldn’t be right. Despite the film’s title translating into English as “to live,” the film poignantly demonstrates how any real meaning life has is barely hanging by a thread. In fact, you would have to be a little crazy — or on death’s door — to act upon this meaning at all. You will be going against the grain, you see. Humanity is organized in such a way to impede meaning. That is, meaning beyond the self-interest, vanity, and hypocrisy of those who seek power.

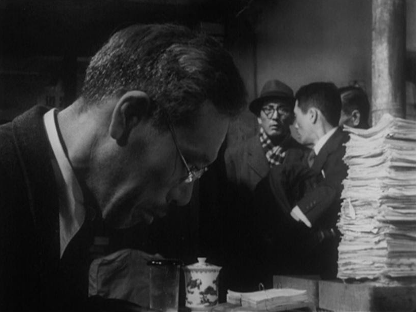

Kanji Watanabe (played by Takashi Shimura) is a petty official in charge of his city’s public works department, and is part of this self-serving machine. He’s a careerist drone who directs an office filled with other careerist drones who count the months and years until it will be their turn to lead the department. But they get little work done, despite being surrounded by mounds of paper. This is the opposite of meaning, and these paper mounds serve as ironic monuments to the work these people are supposed to perform but never do. In an early montage sequence, Kurosawa shows that the very point of their existence in that office is to not work. Or, rather, to shove work onto other departments. And work gets shoved around a lot, it seems.

The great intrusion upon this sad stasis occurs when Watanabe learns that he has stomach cancer. He has six months to a year to live, and so must make up for lost time in his search for meaning. This is the crux of the film, and Kurosawa pursues it masterfully in various ways. The three elements of Ikiru which stood out most to me were the theme of claustrophobic tedium which Kurosawa establishes through set design and camerawork, the use of what I call “the folded plot,” which switches the film’s point of view while still in the middle of the story, and, perhaps most of all, Kurosawa’s use of music, which both underscores and undermines the meaning Watanabe seeks to find in his remaining days. That most of this music is American during a time when the Japanese were only seven years removed from being at war with America invites themes of nationalism into the Ikiru discussion as well.

At first blush, Ikiru is a slow movie. But this is Kurosawa revealing how slow, cramped, and closed-in Watanabe’s life really is.

Kurosawa reinforces this through a drab grayness that pervades his cinematography. He also moves the camera as little as possible. Sure, he tracks the camera on the street following Watanabe with the novelist he befriends or with Toyo, his former subordinate on whom he harbors an innocent crush. But even here, the characters are hemmed in and constrained.

Often he will frame actors as if they are posing for awkwardly intimate portraits. Little seems to be going but the visual dynamism is heavily apparent.

Kurosawa will move the camera for pans or for subtle push-ins. He often gets so close to his characters that there doesn’t seem to be any room to move. Ikiru is a claustrophobic film. There are few open spaces, and in one particular wide shot, Kurosawa expands our sense of claustrophobia until it resembles Hell — a Hell of the mindless multitude, dancing in a haze of cigarette smoke and mambo music.

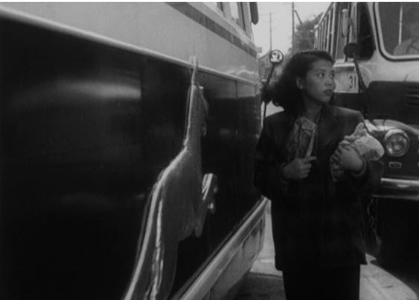

This is the world which Watanabe wishes to escape. Because Kurosawa is so adroit at expressing it cinematically, the audience feels this claustrophobia, even without a jot of dialogue, and wishes that Watanabe escape it as well. But escape it for what? Ikiru teaches us to recognize meaninglessness when we see it — and not just in Watanabe’s uneventful life at the office, but also in his strained relationship with his son Mitsuo, his night of hedonism with the novelist, and with his tragicomic infatuation with Toyo. But is meaning really only a lack of meaninglessness? Or is it something positive and constructive?

You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here [1].

This question gets asked with Kurosawa’s use of the folded plot. During the first half of the story, the audience sees what Watanabe sees and feels what he feels. This is standard movie-going fare with a sympathetic protagonist. However, Kurosawa abruptly changes things by cutting to Watanabe’s funeral when we still have a third of the film left to go. While audiences might find the timing of his death along the plotline somewhat jarring, Watanabe’s dying should come as no surprise. Clearly, his living and dying are not a source of suspense. What is suspenseful is his search for meaning, which we discover piecemeal as his son, brother, and former colleagues try to reconstruct Watanabe’s odd behavior during his last days into a comprehensible whole. All at once, Watanabe is no longer the subject of the story, but its object.

In this, Ikiru resembles Kurosawa’s Rashomon in that the story progresses through flashbacks. But unlike in Rashomon, Kurosawa never stops depicting the truth, despite how the characters interpret Watanabe’s behavior through the filter of self-interest. Before he died, Watanabe accomplished something great. He did so on his own. And he did so against considerable opposition and at great risk. This provides an obvious meaning to Watanabe’s life after the fact. But it also befuddles everyone, especially his colleagues. How could such a mediocrity actually accomplish anything at all? Well, he didn’t actually. It was the mayor who greenlighted the project. It was the local fat cats who let it happen. And it was us, his colleagues, who did a lot of the work as well. Can’t cut us out of the credit, can we?

As the men become drunker and drunker at Watanabe’s funeral, the truth begins to come out. By the end of the evening, they are all praising Watanabe as a great man and vowing to turn their department into a paragon of solicitous industry. But when they arrive at work the next day sober and having second thoughts, you can just imagine how that turned out.

The cinematic element of Ikiru which struck the deepest chord with me is the music. Ikiru makes greater use of diegetic music than any other film I can think of. It’s everywhere, and acts almost like a Greek chorus — constantly harping on the goings-on and providing a weird commentary on this already profound story. As far as I can tell, traditional Japanese music appears once in the film, as Watanabe’s brother plays the radio during Mitsuo’s visit to discuss his father’s strange behavior. Of course, neither man reads the signs properly and constructs a narrative around Watanabe that eludes the truth.

Everywhere else, with one notable exception, the music the characters play and listen to is American — or at the very least Western. This may point to how the Japanese have lost their sense of nationalist pride in the same way that Watanabe’s life has lost its meaning. When Watanabe galivants on the street with his novelist friend at night, we hear Josephine Baker’s “J’ai Deux Amours” [2] being played on an accordion as part of a jazz ensemble. This was around the time in which the novelist claims to be Mephistopheles and declares greed to be a virtue. He takes Watanabe to various clubs in which they play the rhumba, the mambo, and boogie-woogie music. Partying and pleasure-seeking is the nihilist norm in all of this. Is this where Watanabe will find life’s meaning? If anything, Western music seems like an intrusion upon an already besieged Japanese culture, as perhaps represented by Watanabe.

One powerful example of this occurs when Watanabe and the unnamed novelist, after their night of drunken revelry, enter a taxi with a pair of hookers (or maybe they’re just tarts, it’s unclear). In any event, both men are despondent, regretting the time they have just wasted, while the girls just want to have fun. To raise everyone’s spirits, the girls sing the Rosemary Clooney hit “Come On-A My House.” For those who haven’t heard it, “Come On-A My House” [3] is about as amorous and voluptuous as a pop tune can get. If there is an antithesis of traditional Japanese culture circa 1952, this is it. Further, not only do these two Japanese girls sing it poorly, they botch the lyrics. This is the soundtrack to Watanabe’s (and perhaps Japan’s) descent into modernist Hell.

And yet, it’s not as simple as this. Western music in Ikiru also strengthens the poignancy of Watanabe’s struggle. Waldteufel’s “Les Patineurs” plays while Watanabe goes ice skating with Toyo, and it is perfectly appropriate. Jessel’s “Parade of the Wooden Soldiers” plays on the loudspeaker at a café when Watanabe tells Toyo that he is dying. This is a powerful moment because she’s the first person he’s told, and the music bolsters the pathos rather than challenges it.

This goes beyond Western classical music. In the film’s pivotal moment — when Watanabe realizes he must act swiftly and productively give to his life meaning — a nearby crowd of young people sing “Happy Birthday” in English. Watanabe is on the brink of death, yet he is finally born again. My favorite moment occurs early on, as he is sitting at the shrine of his deceased wife in his living room. He hears his son and daughter-in-law playing “Too Young” [4] by Toni Arden on their record player. It’s a gorgeous standard about young love defying the cynical expectations of the adult world. As this music plays, Watanabe remembers his wife’s funeral — clearly, she was too young to die. There is no counterpoint at all here. The music is wonderful and Kurosawa makes the most of it. It does not matter that the music is Western in a story that takes place in Japan.

These three elements coalesce beautifully during the film’s climax. The folded plot unfolds, and we see Watanabe sitting on a swing set in a children’s park, about to die. He is once again the subject of the film as we focus exclusively on him. Kurosawa films this simple scene through lattice monkey bars, reinforcing the claustrophobia of before. Uncharacteristically for Ikiru, he tracks the camera for many seconds with the monkey bars remaining between the audience and Watanabe. This might be the only time Kurosawa moves the camera for such a long period of time without having to follow action. When we finally see Watanabe on the swing unobstructed, the result is liberating, like feeling your arms float upwards after being pressed down for a time. It’s truly a mesmerizing moment, perhaps one of the best in cinema. And it makes sense. After all, Watanabe’s spirit will soon be floating away to a better place.

Kurosawa’s use of music comes full circle in this climactic scene as well. Watanabe is singing, and he is accompanied by the soundtrack. It is a song called “Life is Brief,” a soft, romantic ballad. It may seem like another Western number dominating the soundscape of modern Japan. But it’s not. It’s a Japanese song, written by Japanese songwriters in 1915. In waltz time, Watanabe delivers its melancholy verses, in Japanese. In so doing, he whispers some of the mystery, wonder, and loss embodied in this beautiful film, Ikiru.

Life is brief

Fall in love, maidens

Before the crimson bloom fades from your lips

Before the tides of passion cool within you

For those of you who know no tomorrow

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [6].

Don’t forget to sign up [7] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.