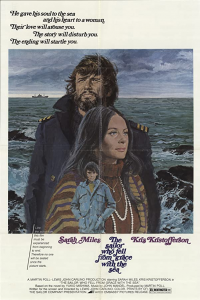

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 1,256 words

1,256 words

Yukio Mishima’s 1963 novel The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea is one of his darkest works. Set in post-War Yokohama, it is the story of Fusako Kuroda, a thirty-three-year-old widow who runs a boutique selling Western luxury goods, and her thirteen-year-old son Noboru Kuroda. (See Alex Graham’s discussion of the novel here [1].)

Fusako’s world is entirely feminine, bourgeois, modern, and Western. She is also deeply lonely. Then she meets Ryuji Tsukazaki, the second-mate on a steamship. Ryuji is ruggedly masculine. Contemptuous of safety and hungering for risk, Ryuji took to the sea out of romantic longings for adventure and glory. But he too is lonely.

Ryuji and Fusako spend a few passionate days together, then he returns to the sea. But they can’t forget one another, and when Ryuji returns to Yokohama some months later, he proposes marriage, which Fusako joyfully accepts.

Fusako’s son Noboru is also attracted to Ryuji. He is a fatherless boy, cocooned in Western, bourgeois luxury. Ryuji represents the exact opposite. Noboru sees the sailor as archetypically masculine and heroic.

But Ryuji constantly disappoints Noboru. First of all, he is just too nice, whereas Noboru longs for hardness. But the last straw is when Ryuji decides to marry Noboru’s mother and quit the sea. Fusako even starts dressing him in smart English suits and training him to work in her boutique.

Sounds like a soap opera plot easily resolved into a happy ending. But this is Mishima, so it is much, much weirder. When we are first introduced to Noboru, he is a peeping Tom, who watches his mother masturbate. Then he watches her make love with the sailor. Noboru also fancies himself a genius and belongs to a small circle of precocious thirteen-year-old Nietzschean sociopaths. This plot element read like a mashup of Hitchcock’s Rope and Lord of the Flies.

The gang starts out by killing and dissecting a cat, then they decide that the sailor can only be restored to his fallen heroic status by being cut up as well. We never actually see this happen, but everything is clearly driving toward it, and it mounts into one of the most suspenseful, gripping, and horrifying final chapters in literature.

Sailor is powerful because it is constructed around deep conflicts: primal family dramas as well as the clashes between land and sea, civilization and the wild, the masculine and feminine, the bourgeois pursuit of happiness vs. the heroic pursuit of glory, and Japanese tradition vs. Western modernity.

You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here [2]

Sailor is a slender, compulsively-readable volume that most people can devour in an afternoon. It cried out for translation and then for a film adaptation. The translation came rather quickly, in 1965. I can’t help wondering how Kurosawa would have directed Sailor in the Yokohama of High and Low [3], or how Hitchcock or Michael Powell would have handled it in a Western setting. But the film adaptation of Sailor ended up in the hands of a very different director and appeared in 1976.

I avoided the film of Sailor for a long time, for two reasons. First, the book may be a masterpiece, but I found it intensely disturbing, and I didn’t really want to see it on film. Second, the film is not set in Japan but in England, which I thought would undermine one of the deep dramatic conflicts in the book, which is between Japanese tradition and specifically English modernity.

Mishima puts all the pieces in place for a very happy ending. Fusako has found a husband, and Noboru has found a father figure. If the novel were set in England and written by Jane Austen, the happy ending would have been a wedding. But this is Mishima’s novel, set in Japan, so all our hopes are dashed in the most perverse way possible because, to quote Nietzsche, “Man does not strive for happiness; only the Englishman does that.”

I am sorry I hesitated to watch The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, for it is a very good film. Sailor was the directorial debut of John Lewis Carlino, who had a long and distinguished career as a screenwriter, including John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, Mark Rydell’s film of D. H. Lawrence’s The Fox, the fascinating sociopathic buddy film The Mechanic starring Charles Bronson and Jan Michael Vincent, and Anthony Page’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. Carlino went on to direct only one more film, The Great Santini (1979), his adaptation of Pat Conroy’s novel of the same name.

Fusako and Noboru Kuroda become Anne Osborne and her son Jonathan, played by Sarah Miles and Jonathan Kahn. Industrial Yokohama becomes quaint Dartmouth, in Devon. Fusako’s Western import boutique becomes a select antique shop. And the sailor, Ryuji Tsukazaki, becomes an American, Jim Cameron, played by Kris Kristofferson.

The casting and acting are uniformly good. All three main characters are convincingly brought to life, with almost no friction transforming them into whites. Miles’ performance as the mother is the best. Some might claim Kristofferson is wooden and inarticulate, but that’s how the character is supposed to be played. He does, however, convey genuine warmth and humanity. There is real sexual chemistry between Miles and Kristofferson.

The gang of sociopathic schoolboys becomes even more realistic and chilling in the English context due to their posh accents, public school uniforms, and constant bullying and backbiting.

Carlino masterfully adapts Mishima’s story to the screen. It is easy, because Mishima’s novel is short, and there’s quite a bit of dialogue. Moreover, Carlino chooses the exact right bits of interior monologue to dramatize. The most repulsive scene in the book is the killing and dissection of the cat. Carlino handles it admirably, removing the grossness but not the horror. Finally, he fully realizes the almost unbearable suspense Mishima generates in the last pages.

A few things don’t quite fit, though. For some reason, I did not find it odd that an upper-middle-class Japanese widow would casually enter into a sexual relationship with a sailor in 1950s Japan, but it seemed very odd for an English widow of her class, even in the 1970s.

The settings, moreover, are very different from the novel. Yokohama is urban, industrial, and gritty. This underscores the difference between the wild beauty of the ocean and the ugliness and artificiality of urban life. Dartmouth, however, seems small, quaint, and very beautiful, and it is surrounded by scenic countryside and seacoast.

Scenes that in the novel take place indoors or in seedy industrial settings are filmed outdoors. There is a great deal of stunning landscape photography. The interiors of the Osborne house and shop are also beautifully appointed, and the camera lingers on the details like decorator porn. The music is middlebrow classical.

In fact, the whole film is shot like a Masterpiece Theatre period drama, only with nudity, masturbation, sex, voyeurism, animal cruelty, and murder. If Carlino’s aim was to be unsettling, he succeeded wildly. Like the novel, the film is brilliant, troubling, and difficult to enjoy — but it is well worth the effort.

Unz Review [4], September 2020

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.