The Anglo-Indian Race War of 1857

Posted By Kathryn S. On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledIt began with whispers. In what should be a familiar script, false narratives and unsubstantiated rumors about white treachery ignited nonwhite hysteria—murders, riots, and fires consumed the countryside. It was the most traumatic episode for the British in the nineteenth century, and it took place thousands of miles and oceans away from Europe. While not exactly obscure, it has become a historical footnote with which many educated people have next to no familiarity (at least on this side of the Atlantic).

No other colonial disaster equaled the fever-pitch intensity among the public than that conjured by the Indian Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. Charles Dickens, a man not known for his support of British imperialism, was also swept up in the fervor. In a letter to a friend composed in October 1857, Dickens wrote:

I wish I were Commander in Chief in India. The first thing I would do to strike that Oriental race with amazement . . . should be to proclaim to them . . . that I considered my holding of that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested; and that I was there . . . to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth. [2]

Well, I’ve always thought his tone betrayed some amount of admiration for Madame DeFarge, who dominated every page into which he wrote her. But Dickens was far from alone in calling for an updated Requerimiento. Neither were responses to the Mutiny confined to Britain, but Americans also worried about the debacle. South Carolinian Mary Chestnut shivered when she observed that “their [Indian] faces were like so many of the same sort at home.” [3] The revolt of nonwhites against whites on the far side of the world stoked southern fears of a black slave revolt unleashing similar horrors in their own corner of the world. [4] Vivid stories of the Indian Mutiny may have contributed to southerners’ charged reaction to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia just two years later. The specter of roving bands of men with dark faces and gleaming white grins, rape and murder on their minds, haunted the South and escalated sectional tensions. Opinions hardened, and militias doubled in both size and resolve.

Doubtless, much of the fuel feeding the British and American frenzy was based on wild storytelling repeated and spread by a propaganda press. Nineteenth-century newspapers were arguably worse sensation-whores than today’s rags. A look into the Gilded Age muckrakers and their reporting, which gleefully pored over every forensic detail of the latest outrage, should prove to anyone that the media is what it always was. Jack the Ripper had no more devoted and enthusiastic cheerleaders than the London press. In the case of the 1857 Mutiny, the true stomach-turning incidents of barbarism served to make the less-true seem plausible. Fitting, as it all started with a hate hoax.

By the spring of 1857, the sepoy (or native Indian) regiment in Meerut, forty miles from Delhi, decided enough was enough. Already, the British had arrested and executed one Indian soldier who had protested the army’s equipment, then they had publicly shamed the rest of his supporters. Now, their own British officers planned to force them all to drill while using the new shipment of Enfields, rifles patented a few years prior and making the rounds across the Empire. Most of the sepoys from Bengal were proud members of the upper castes—men like the Rajputs and other “martial races” of northern India. They were sensitive to anything that might impugn their status or honor.

The Enfield rifle that so concerned these warriors came with a grooved barrel that shot a Minié ball in a tight spiral, resulting in the gun’s improved distance and accuracy. The rifles themselves weren’t the problem; the pre-greased paper cartridges of gunpowder that came with them were. In order to use the cartridges, soldiers had to bite and/or tear them open in order to pour the powder down the gun’s muzzle. [5] This process necessitated the mouthing of small quantities of the lubrication that greased the packaging. No one knew where or how the rumor started, but it spread through the sort of grapevine, universal to the colonized and inscrutable to the colonizer, that soon led to large portions of the British East India Company’s native army rising up in open rebellion. The grease on the cartridges, so the rumor went, was deliberately made from beef and pork tallow in order to insult the Muslim and Hindu faiths. [6] The British planned to have their sepoys eat the fat rendered from forbidden animals, thus making them low-caste ex-communicants who would be barred from returning to their homes and families. It would sever ties to their religion, furthering the ulterior motive that they were convinced the British had, of converting them to Christianity. Something had to be done.

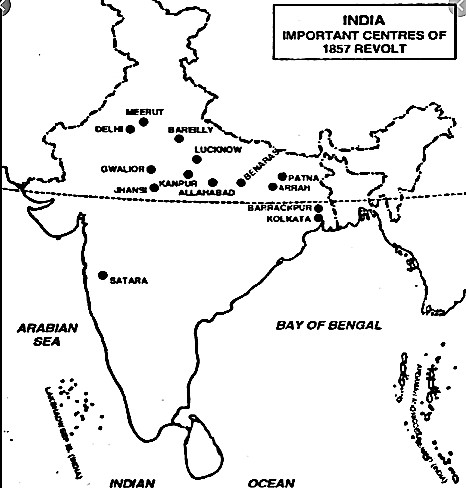

On the morning of May 12, 1857, a dispatch from Meerut arrived for Captain Henry Parlett-Bishop of a Bengal artillery unit. His diary entry for that morning was terse and unnerved: “heard . . . by runner (telegraph wires having been cut) that serious disturbances had taken place, collision between sepoys and European officers, in which several of the latter had been killed.” [7] Indeed, the sepoys at Meerut had murdered their British commanders during the night and then marched to Delhi, seat of the diminished Mughal Empire. There, they joined other comrades in that city and proclaimed the Mughal Emperor, Bahādur Shah II [2], restored to power. With a base of operations in place, the local mutiny became a popular revolt in which the Emperor’s sons, including the infamous Nana Sahib Peshwa; lesser Indian aristocrats, frustrated at British seizure of their lands and rents; and peasants, who resented British reforms that threatened their traditional lifestyles—all rose up in a conflagration engulfing much of the north and central states. The British officially had a crisis on their hands. How had it come to this?

India and the British, Pre-Mutiny

Like most catastrophes that seemed to come out of nowhere, subtle but mounting levels of friction over the course of many years finally caused the fault-lines of social resentment to crack the earth in two beneath the imperialists’ feet, destroying their illusions of British control and Indian docility. At the time of the Mutiny, around 45,000 whites and some 300,000 Indians were serving in India’s British army. Imperialism was always a dangerous business for Europeans, but it proved too addictive a sport for them to give it up. We also have it partly to thank for the current fashion of welcoming suicidal levels of nonwhite immigration now flooding our white countries. In earlier centuries, however, imperialism summoned the best of the enterprising individualism that stoked Europeans’ desire for glory and wealth. This, paired with a collective spirit issuing from the “strong gods” of monarchy, nation, and church, bolstered individual efforts with purpose. [8] These two forces made the age of exploration and colonialism/imperialism, from the end of the medieval era in 1492 through the age of industrial modernization up to 1914, the most astounding half-millennia of imperial success since that of ancient Rome. [9] By the mid-nineteenth century, the British Empire in particular had made global conquest an obsession. In 1857 Britannia’s possessions spanned six continents—but the jewel of her empire was India.

Unlike most of Britain’s other territories, India had an enormous population. Its societies and cultures were interesting and sophisticated. Despite being isolated by the imposing Himalaya Mountains in the north and the Hindu Kush to the west, India was a land of conquests. The British were just the latest in a long line of invaders who included: Aryan Indo-Europeans, ca. 1500 BC, the Persians (briefly), ca. 500 BC, and Alexander the Great (even more briefly) in 326 BC. The Turks, Arabs, Safavids, and Mughals followed them. These earlier visitors crossed over into India through the narrow valleys and passes, like the Khyber, in Afghanistan. By the time the British made their presence felt in the region by sea during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the India they found was an ancient land of deeply-ingrained cultural practices that had assimilated conquerors from outside its borders as much as it had appropriated from them. Many of its people adhered to a strict caste system and were divided between the religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. Navigating these practices and landscapes was a monumental task for the British and required the cooperation of Indians themselves.

Before the 1857 Mutiny, the British government did not directly rule India, but operations in the Subcontinent were carried out through the British East India Company (EIC), an entity that began as an ostensibly private enterprise funded by British shareholders (the government would eventually buy large shares of the Company). Its most important investment was in the Indian spice trade. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Britain found itself in competition with other European traders, who also wished to increase their economic footprint in India. The Seven Years War (1756-1763), fought principally by the British, Prussians, and their allies against the French, Austrians, and their allies, was a world war. Its outcome thus had similarly wide-ranging consequences, one of them being the strengthening of the British presence in India at the expense of other Western powers.

The Battle of Plassey in 1757, fought between the EIC’s “private” army under the command of General Robert Clive, and that of the armies of the Nawab (or King) Siraj ud-Daulah of Bengal, who was supported by the French, cemented British gains in the northeast. One of the motivating factors for the British were reports that some months ago ud-Daulah had locked almost 150 British soldiers and civilians overnight inside a Calcutta dungeon cell. It was a room only meant to hold three prisoners at once. Most died from the heat and the crush. The dungeon came to be known as the “Black Hole” of Calcutta.

At Plassey, Clive had his vengeance and bribed Indian commander Mir Jafar Ali Khan to betray the Nawab. When the battle was at its most desperate, Jafar defected and refused to go to ud-Daulah’s aid. Instead, he kept his force behind on the left flank, and contented himself with observing the carnage. Soon after, his new British allies captured ud-Daulah and declared victory. They executed the Nawab and installed Jafar on the vacant Bengali throne as promised. For the remainder of the eighteenth century, the Company steadily acquired more territory, and those parts of India they did not directly control, they influenced through a combination of threat and favor aimed at Indian potentates.

For many Britons, India was a huge rehab facility. Third sons or disgraced army officers could get away from their countrymen and either redeem themselves through colonial service or set themselves up in a place where they could be admired as bigshots in a way that would have been impossible had they stayed home. General Charles Cornwallis enjoyed a second and illustrious career as a governor-general in India after his embarrassment at Yorktown. He was responsible for winning the Third Anglo-Mysore War in 1792 against the Mysorean ruler, Tipu “Tiger” Sultan. Tipu was himself a fascinating man and one who loved to collect European literature and art. He filled whole rooms of his palace with “mirrors, clocks, telescopes, and porcelain” from the West. [10] After his final defeat and death in 1799, following the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, the British found among Tipu’s possessions a French-made mechanical sculpture that produced eerie sounds from a built-in organ: it was a tiger ripping out the throat of a prone and wailing Redcoat. This was too good a treasure to pass up, and the British shipped it to England, where it now belongs to the Victoria and Albert Museum of colonial curiosities.

In the early days of British incursions into India, the men who traveled there usually did not bring wives, and so race-mixing and all manner of interracial relationships were common. So many British transplants ended up adopting the lifestyles and norms of the Indian people that “going native” became an entire genre of moral-panic literature. Parliament began a tradition of blaming the EIC’s mismanagement and corrupt tax collecting policies on its officials having come down with a bad case of the tropical disease known as “eastern despotism.” While the British foothold in India remained tenuous, this quasi-assimilation was a strategic necessity (one at which their French rivals were masterful). Winning and keeping the good graces of the population and the regional princes was essential.

By the nineteenth century, strategic necessities had shifted. While the British still relied on elite Indian cooperation, their strengthened position gave rise to a new kind of colonialism and philosophy. Britons began moving to India with their wives and families. English schools and churches for whites and Indians alike were built; missionary efforts grew apace; tax laws were “reformed” to benefit the Company. The British were making themselves at home in India and bringing modern Western ideas and infrastructure with them.

It was all going so swimmingly, that Indian Supreme Council member Thomas Babington Macaulay, a great champion of education and of making English the preferred Indian language over Arabic and Sanskrit, proclaimed whiggishly that “India may expand under our [British] system till it has outgrown that system . . . having become instructed in European knowledge, they [Indians] may, in some future age, demand European institutions.” That day, Macaulay declared, “will be the proudest day in English history.” And that day would, apparently, demote Agincourt to number two on the depth chart. The British had “found a great people sunk in the lowest [pit] of . . . superstition, [and] to have so ruled them as to have made them desirous and capable of all the privileges of citizens, would indeed be a title to glory all our own.” [11] This lofty pronouncement in 1833 might have been the first (but far from the last) time that a colonial leader announced plans to give up his colony in anticipation of a show of righteous magnanimity. To his astonishment, I’m sure, it wasn’t love for British “instruction” and “knowledge” that caused many Indians to demand that the British leave two decades later; it was, rather, their disdain and hatred of these “European institutions.” A “great” number of the “people” of northern India rejected Macaulay and his Western paternalism, choosing instead to speed independence along through rebellion.

The Mutiny and Its Aftermath

By June of 1857, the mutineers had ensconced themselves in Delhi and were sending riders out to the surrounding area, stirring up unrest. A number of Indian aristocrats and their tenants throughout the north joined the tumult. Fear plagued the whites in the British army. In a letter dated June 6, 1857 in the town of Lucknow, Lieutenant Octavius L. Smith asked his mother to pardon his writing, and

If [it] is illegible my descriptions wild and the least bit disconnected and my letter otherwise a failure you must attribute it to the ‘Mutiny’ and its effects . . . News has just come in . . . that a plot was overheard concocted . . . to murder all the officers in the Native Regts tonight . . . We all have pistols, some revolvers, others horse pistols . . . [12]

Smith and the other white officers no doubt barred their doors that night. If sleep came at all, they captured it fitfully in their beds, pistols clutched to their chests.

The British and their loyal Indian soldiers recaptured Delhi, then deposed the Emperor. But by that time, Nana Sahib’s followers were on the move, and in June they and defecting sepoys laid siege to the compound at Cawnpore. Outnumbered and with little hope of deliverance, General Hugh Wheeler agreed to surrender his position in return for the safe passage of his troops, along with their wives and children. This decision turned out to be a fatal mistake and one mirroring the Fort William Henry Massacre that took place almost exactly one hundred years before, during the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years War). As the British and their Indian allies left the compound in preparation to cross the Ganges River, sepoys descended on them from all directions. Others attacked the wounded men lagging behind the train with swords and kukris (Indian machetes). After the killing began to slow, cavalrymen rode into the water to finish off any of the men left alive. Only four of those men managed to escape. The two hundred surviving British women and children were then herded back to Cawnpore as hostages.

These prisoners languished for over two weeks in a small building that facilitated the spread of deadly bouts of cholera and other diseases—until Nana Sahib received word that British troops would soon arrive and likely force him out. What happened next is still the subject of debate, but according to most contemporary accounts, Nana Sahib decided that his hostages had to be gotten rid of. [13] So, he ordered the sepoys under his command to kill all of the women and children. When they refused this order, Nana Sahib supposedly found local butchers to complete the task. In a scene from hell, the hired killers went about their bloody work for some hours and hacked the two hundred civilians to pieces with their knives and cleavers. They then shoved the victims’ remains down a well. Some were still alive when they found themselves thrown in and buried beneath their dead and mutilated loved ones. Readers may gasp at this graphic depiction, but I’m downplaying it.

After the British retook Cawnpore in mid-July, they discovered the brutal scene and its ghastly well of horrors. Overcome with tears of shock, then revulsion—and, finally, a hatred lacking words to describe it, the British changed their tactics. No longer would they fight a war of recovery, but a war of retribution. Reprisals within Cawnpore were terrible. The British rounded up those they believed responsible for (or at least not conclusively innocent of) the massacres. Some unlucky Indians were compelled to lick the blood from the floors and walls where the murdered whites had been chopped to pieces by their countrymen. Others found themselves forced to eat raw pig and cow meat while they submitted to whippings doled out by low-caste servants. Only after enduring these humiliations were they hanged.

After Cawnpore, the theater of war shifted to the embattled city of Lucknow, besieged by the mutineers. From the beginning of June to mid-November 1857, the men and women trapped in Lucknow suffered torments, both emotional and physical in nature. Disease and malnutrition decimated whites and Indians alike. Katherine Bartrum, the wife of an army surgeon, wrote in June of her household of refugees, “We received letters from our husbands telling of their escape from Gonda . . . [and] grateful were we, to think that they had . . . been preserved,” and “we began to hope that . . . we might meet them again.” By July, several members of her group had died, and an anguished Katherine confessed that “Everyone is getting dispirited; no news of relief; they say we are forgotten & that re-inforcements will never appear.” Her account read like a roller-coaster of emotions, one day joyfully recording the news that rescuers were coming, and the next, despondently admitting in her diary that celebration had been premature. Finally, on November 17, she dashed off the hurried line: “Heard we are to leave Lucknow tomorrow night with just what we can carry . . .” [14]

By the end of 1857, EIC forces had retaken control of most military forts and towns. Their harsh policies included wiping out and burning whole villages, striking fear into rebel hearts and crushing their morale. Though irregular fighting continued into early 1858, it was by then a mopping-up campaign. A treaty in July of that year officially ended hostilities. Rebel leaders and Indians convicted of war crimes stared quite literally down the barrel of British vengeance. The army arranged for a dramatic spectacle of mass executions that India would not soon forget. Artillerymen strapped those guilty individuals to the mouths of cannons, then lit the fuses. Nana Sahib had meanwhile disappeared, never to be heard from again—at least not by the British. I would hazard a guess that he fled north to Nepal or Afghanistan, a favored spot for hunted men. That, or he was killed and left to rot anonymously in the dust.

I should note that the majority of Indian soldiers remained loyal to the British. Few powerful Indian aristocrats, who might have profited from a British defeat, made the decision to aid the revolt. Neither the better part of central India nor that of southern India participated, making conceits held by present-day Indian nationalists and academic post-colonialists that the Mutiny was the “First War of Indian Independence,” politicized grandiosity. It would be a mistake to attribute all of the loyalty/neutrality of most Indians to warm feelings for the British; much of central and southern India’s coolness toward the rebels was the perception in those places that the Mutiny was a Muslim affair; Hindu southern India had little desire for the prospect of replacing the British with the Islamic Mughal emperor. Regardless of rebel support or lack thereof, the Mutiny of 1857 was a race war. The less than full support among the native population for the sepoy rebels and their cause proved only this fact: it matters not how many nonwhite “allies” whites have; there will always be a grinding friction present, punctuated by violence, wherever significant populations of whites and nonwhites live amongst each other. Atrocities have occurred in every war. But atrocity as a military strategy has occurred only in race wars with more than territory at stake. Both the British and the mutineers made atrocity their central tactic when waging the struggle.

In the aftermath, the British government dissolved the EIC’s authority, and India became a territory of the Crown, directly ruled by Queen Victoria (now Empress of India) in an arrangement known as the Raj. The following decades were filled with British self-reassurances that their revamped colonial government had fixed all of the problems and abuses committed by the EIC, whose incompetence had presumably led to the Mutiny. They engaged in a PR offensive that romanticized India and exaggerated Indian love and fealty to Britain and the Queen. It was something like that other late nineteenth-century reconciliation campaign going on in America, but less convincing (due probably to the fact that American ex-combatants were from the same racial stock). More cynical observers noted that “The rebellion created a legacy of racial hatred which permeated all aspects of the relationship between the ruler and the ruled.” [15] At the very least, the Mutiny resulted in years of suspicion and dread.

Sleepwalkers

When reading primary source accounts of the Mutiny and the reaction it provoked, I was not only impressed by the horror but the shock expressed by colonial officials and civilians, all of whom assumed that everything was fine before the shooting started. An October 1857 article in the London Times wondered at the sudden murderousness, for Indians were, “to all appearance, quiet, prosperous, satisfied. English rule and English law were gaining ground every day, and the rule of a hundred years seemed to have produced . . . an established obedience and a natural loyalty.” [16] European tourists and travelers once felt safe in the Indian countryside, their letters home remarking on “the country along the Ganges . . . well-watered with fine crops, thickly interspersed with Date trees . . . The road alive with pilgrims to the Devi Temple. . . women in coloured and chequered and gilt flowered silk, . . . carrying or leading goats for sacrifice.” [17] They regaled their relatives back in England and Scotland with lively descriptions about the “Great Mussulman feast[s] during the whole of which time there [was] an incessant beating of tum-tums, . . . beating of breasts and all the Mussulman world [cried] out” on the nights of their holy feasting. [18] India and its people were exotic and colorful, certainly nothing to worry about.

By 1858, something had shifted. Which echoing “tum-tum” sounding from afar was god-praise, and which was war-beat—and was there a difference? Which of the women clad in brightly “chequered” sashes went to the temple to pray for peace, and which of them prayed for vengeance? As white tourists and veterans rode by villages and heard the drums, banging out their alien songs and summoning the faithful to feast, no longer did they dismiss the dark-eyed looks peering at them through leaves and window-slits as the looks of over-awed primitives, nor their songs ones of harmless flatteries to false idols. They understood now that these were the looks of hunters, whose feline gazes only appeared dull before the killing-lunge; these were the songs of living gods, whose worshippers, to continue their reverence, would paint their fingers, arms, and faces the deep scarlet of fresh-slain sacrifice, the carcasses that dripped down from their feasting tables belonging to neither goat nor lamb, but that of Britisher. All this they now saw in the gaze of every “loyal” sepoy and servingman, from whom they turned away and shuddered.

The true cause of the 1857 Race War was not animal fat. It was the Indian realization that the British were not there simply to make money in India. They were there to make over India in their image—the Pygmalion project at the heart of all colonial empires and one that hinged on the outcome of the replacement of one defeated people for another. Monstrous behavior aside, it is hard to blame the Indians for their desire, if not their execution of it, to throw off the British yoke. They understood that either the British would permanently settle, continue to bring their wives and families, and transform India into the Britain of the Orient by gradually displacing its native peoples and cultures with their own; or else, India would cannibalize the British, spitting up and out forever those Britons she did not utterly consume. Colonists made the sparsely populated areas of North America and Australia over in their image, because they pushed indigenous inhabitants out and to the brink. The Spanish and Portuguese in Latin America prevented something similarly dramatic from happening, but they did so at the cost of abolishing themselves through mass interracial breeding. This eliminated much of the pure European bloodlines in their territories and led to the rise of a new and increasingly resentful mixed-raced population—those who directed their impudence toward Europeans and channeled their contempt toward the indigenous people left in the countryside.

Another fate awaited the whites in Africa and India. Colonial officials and administrators, educated at Eton and Oxford, forgot the history lessons that should have warned them that liberal reforms, introduced to populations suddenly and inorganically, created and then did nothing to satisfy rising expectations, but they only whetted an appetite for revolution. The British thought that their advanced civilization and minority rule would exempt them from the law of demographics; that Indians and black Africans would love them and be grateful for the British “civilizing mission” that brought the colored races up and into the “enlightened” age. They sentimentalized imperialism to flatter themselves. This is a harsh assessment of a group I admire; especially considering that in the nineteenth century, most of the British sincerely believed that they could help raise the world from the depths of ignorance—it was their duty, even! But they had too much esteem for their benevolence and too little respect for Nature, thinking themselves her masters, when she was all along the great shaper of her human subjects. Civilization has never been a victory over her iron law of demography—over man’s instincts—but its ultimate and evolved expression of her will. Every civilization, past and present, has been the result of one people triumphing over others. The same has been true of every civilization’s downfall. Dickens said more than he knew in that intemperate letter when he spoke about “extermination,” and revealed more about human tribalism than he meant, when he fantasized about “razing” the “Orientals” “off the face of the earth.”

There is nothing nice about it, but the Mutiny proved what has always seemed to be the case when two (or more) vastly different groups have occupied the same territory. The people belonging to the one will think of those belonging to the other and say to themselves, sometimes wistfully and sometimes wrathfully, “how much better it all would be—if only they were gone.”

Notes

- The illustration is entitled, “The Indian Shows Off the Enchanted Horse before the King of Persia,” in Andrew Lang’s, The Arabian Nights Entertainments (London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1898), 359.

- Charles Dickens, “Letter to Angela Burdett-Coutts, October 4, 1857” in Letters from Charles Dickens to Angela Burdett-Coutts, 1841-1865, ed. Edgar Johnson (London: Jonathan Cape, 1953), 298.

- Mary Boykin Chestnut, Mary Chestnut’s Civil War, ed. C. Vann Woodward (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Press, 1981), 418.

- See Nikhil Bilwakesh’s “‘Their Faces Were Like So Many of the Same Sort at Home’: American Responses to the Indian Rebellion of 1857,” in American Periodicals 21, no. 1 (2011) pp. 1-23. This article means to make Chestnut and her contemporaries look benighted instead of insightful. It fails.

- The Pattern 1853 Enfield (not to be confused with the later Lee-Enfield) was a muzzle-loading, black powder musket with a rifled or grooved barrel, rather than the smooth bore of earlier muskets. As stated, the rifled barrel design fired a Minié ball (a French-designed conical bullet) that spun out, rather than simply projected up and out. Like today’s cartridges, the Enfields’ cartridges were each filled with powder and a bullet, but they were made of paper rather than our modern brass or steel-jacketed cartridges. Both sides used this rifle (and the Springfield) during the War of Southern Secession. This video by “britishmuzzleloaders” is a good demonstration of how to load and fire an 1853 Enfield: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CNIt8RvGP5M

- Grease used for the cartridges was likely a mixture of beeswax and tallow, or animal lard, though it’s unclear what kind of animal lard made up the tallow; deer and bear grease were popular animal fats used, but it’s possible that pig and/or cow fat coated some of the cartridges as well. If this was the case, then the British and the EIC were stunningly thoughtless.

- Henry Parlett Bishop, “Diary Entry, Dated May 12, 1857” in India During the Raj: Eyewitness Accounts, ed. David M. Blake, Collection of Diaries and Related Records, British Library in London http://www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/india_during_the_raj_parts_1_and_2/Publishers-Note-Part-2.aspx

- See R. R. Reno’s The Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West (New York: Regnery Gateway, 2019).

- There’s a long historiography on the differences and definitions of “imperialism” and “colonialism.” For the purposes of this essay, “imperialism” refers to the broad use of power and influence that a particular state exercises over other states or territories, with a premium placed on values and/or economics that form a guiding philosophy of empire. “Colonialism” is a form of imperialism in which outright governmental control and settlement issuing from the “Mother Country” (and sometimes from its other colonies, as was the case when Indians moved to southern Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) are prominent features. An example of imperialism but not colonialism was the “Open Door Policy” in China, which granted Britain and other Western powers, along with Japan, favorable access to Chinese trade; but apart from Hong Kong, the British had no colonies in China.

- Maya Jasanoff, “Collectors of Empire: Objects, Conquests and Imperial Self-Fashioning,” in Past & Present, no. 24 (August 2011), pp. 109-135, 121.

- Thomas Babinton Macaulay, The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay, Popular ed. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1889), 572.

- Octavius Ludlow Smith, “Letter, Dated June 6, 1857,” in India During the Raj.

- There is some controversy over whether Nana Sahib gave the order to kill the hostages, or if one of his lieutenants did so without his knowledge. This alternate theory may seem to strain credulity, but the Mutiny was a chaotic affair in which leadership, particularly among the rebels, was weak and diffuse. It is not beyond the realm of possibility to imagine that someone took it upon himself to “fix” the problem of the captives independently of Nana Sahib. Nevertheless, I go with what I believe most likely happened.

- Katherine Bartrum, “Diary Entries, Dated June 12, August 17, and November 17, 1857,” in “India During the Raj.”

- Tapan Raychauduri, “British Rule in India: An Assessment” in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, ed. P. J. Marshall (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996) pp. 357-369, 359.

- “Sepoy Mutiny,” in the London Times, October 24, 1857, A6.

- John Russel Colvin, “Diary Entry, Dated June 15, 1837,” in India During the Raj. Colvin was Private Secretary to Governor-General Lord Auckland and later Lieutenant-Governor of the North Western Provinces until 1857.

- James Fenn Clark, “Diary Entry, Dated December 1846,” India During the Raj. He wrote these entries during a visit to his father, Hezekiah Clark, of the Bengal Medical Service, and during his subsequent travels.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [7] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [8] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.