De Descriptione Temporum: A Description of Our Times

Posted By Fenek Solère On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 2,224 words

2,224 words

If they embark on this course, the difference between the old and the new education will be an important one. Where the old initiated, the new merely “conditions.” The old dealt with its pupils as grown birds deal with young birds when they teach them to fly; the new deals with them more as the poultry-keeper deals with young birds — making them thus or thus for purposes of which the birds know nothing. In a word, the old was a kind of propagation — men transmitting manhood to men; the new is merely propaganda.

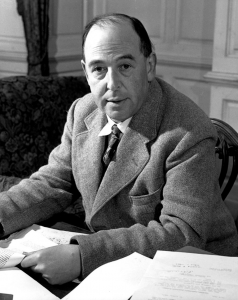

— C.S. Lewis

When C.S. Lewis, a man who famously described himself as “tall, fat, rather bald, red-faced, double-chinned, black-haired, deep-voiced, and wearing glasses for reading,” came to present his inaugural lecture as the new Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge University on November 29th, 1954, he chose De Descriptione Temporum as its title and mounted a rigorous defense of the “Old West” and “Old Western Values.”

For, having arrived at the ripe old age of 56, the now-famous author whose trousers were usually in dire need of pressing, his jackets threadbare and blemished by snags and food spots, and his shoes scuffed and worn at the heels, had already been passed over numerous times for the Chair of English at Magdalen in Oxford, despite his having an impressive list of publications which included The Allegory of Love (1936) and English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (1954).

His newfound love, the down-at-heel Jewish poet and novelist Joy Davidman Gresham, an Oxbridge Yoko Ono who upon reading Lewis’s works had seemingly been instantly converted to the faith of the cross, and who is often blamed for blighting the Lewis and Tolkien friendship, described the lecture thus:

. . . brilliant, intellectually exciting, unexpected, and funny as hell — as you can imagine. The hall was crowded, and there were so many capped and gowned dons in the front rows that they looked like a rookery. Instead of talking in the usual professional way about the continuity of culture, the value of traditions, he announced that “Old Western Culture,” as he called it, was practically dead, leaving only a few scattered survivors like himself. . .

By “like himself,” he meant the baggy-trousered traditionalist incorrigibles walking the medieval city’s narrow lanes and meandering under the Bridge of Sighs. Colin Duriez, in The Oxford Inklings (2015), adds that “Lewis defined the Old West by placing it in sharp contrast to our modern world. The Great Divide, he believed, occurred somewhere in the early nineteenth century. It was as much a social and cultural divide as a shift in ideas and beliefs. On the other hand, Lewis saw positive values in pre-Christian paganism that prefigured the Christian values he so championed.”

Indeed, Lewis’s portfolio of Christian apologetics, already extensive by the time of his move to Cambridge, included The Pilgrim’s Regress (1937), The Problem of Pain (1940), The Screwtape Letters (1942), The Great Divorce (1945), Miracles (1947), and Mere Christianity (1952), and continued to grow even longer after he had relocated to his Oxford College’s namesake, Magdalene, at Cambridge, with Reflections on the Psalms (1958) and Letters to Malcolm (1964).

These titles were to sit proudly alongside his other fictional works, like Out of the Silent Planet (1938), That Hideous Strength (1945), and his Christian-oriented Narnia fantasies, which began with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950).

Yet Lewis, who had walked the cobbled quads for many a long year before he had his epiphany that God must indeed exist while sitting on a bus climbing up Oxford’s Headington Hill, was only too aware that the paganism to which he adhered belonged, as Duriez continues, “to a vast period of continuity that predated the Middle Ages and included the classical antiquity of Greece and Rome.” This realization caused him to declaim that “Christians and Pagans had much more in common with each other than a post-Christian. The gap between those who worship different gods is not as wide as that between those who worship and those who do not.”

Lewis defined post-Christian modernity as “the age of the machine,” a notion that held a distinct resonance in the fictional works of Tolkien’s Ring Trilogy and some of Lewis’s own fictional oeuvre. The new incumbent of the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature concluded his monologue with a blistering attack on modernity:

Between Jane Austen and us, but not between her and Shakespeare, Chaucer, Alfred Virgil, Homer, or the Pharaohs, comes the birth of the machines. . . this is parallel to the great changes we divide epochs of prehistory. This is on a level with the change from stone to bronze, or from a pastoral to an agricultural economy. It alters Man’s place in nature.

Lewis contends rather prophetically that “speaking not only for myself but for all other Old Western men whom you may meet, I would say, use your specimens while you can. There are not going to be many more dinosaurs.”

This assertion led to an immediate riposte to his apparently “reactionary” views, with the February issue of Cambridge’s 20th Century being given over to twelve articles, including one by the author E. M. Forster, stressing the need for humane values and “the importance of free liberal, humane enquiry, which they conceive to be proper not only to a university community but to any group that claims to be civilized.”

By “humane,” Lewis, who was greatly influenced by the fiction of G. K. Chesterton and fellow Inklings like Charles Williams and Owen Barfield [1], believed the progressives meant “Orthodox Atheism.” He repeated the tenets of his controversial lecture, much to the chagrin of his academic adversaries, in a well-received two-part monologue entitled The Great Divide on the BBC in April 1955.

You can buy Fenek Solère’s novel Rising here [2]

So, far from being the human equivalent of the Big Bell in the Tom Tower of Christchurch, tolling five minutes past the hour, Lewis was in truth a gifted orator successfully advocating for what he interpreted as Western values through the lens of a fervent convert. One of many initiators of a minor Christian literary renaissance, a new romantic theology, a rearguard action in defense of what was increasingly seen, in Duriez’s words, as “cast-off values and virtues that [Lewis] felt were germane to our very humanity.”

His fellow travelers on this crusade included T.S. Eliot with his Ash Wednesday (1930), The Rock (1934), Murder in the Cathedral (1935), and Burnt Norton (1936); Dorothy L. Sayer’s The Zeal of Thy House (1937) and a play The Devil to Pay (1939); Helen Waddell’s Peter Abelard (1933); James Birdie’s Tobias the Angel (1930); Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory (1940) set against the Mexican Cristero War of 1927-1919; and other emergent talents like Evelyn Waugh with his Edmund Campion: Jesuit and Martyr (1935) and historical novel Helena set in Christian Constantinople (1950); and the Scottish poet, novelist, and translator, Edwin Muir, who had a religious experience while visiting St. Andrews and from then onwards thought of himself as Christian and saw Christianity as revolutionary as socialism. Muir once wrote in his diary in the late 1930s:

I was born before the Industrial Revolution, and am now about two hundred years old. But I have skipped a hundred and fifty of them. I was really born in 1737, and till I was fourteen no time-accidents happened to me. Then in 1751, I set out from Orkney for Glasgow. When I arrived I found that it was not 1751, but 1901, and that a hundred and fifty years had been burned up in my two-days’ journey. But I myself was still in 1751, and remained there for a long time. All my life since I have been trying to overhaul that invisible leeway. No wonder I am obsessed with Time.

Lewis and his circle of fellow Inklings, sharing a round of beers in the smoky snug of the “Bird and Baby,” would probably have concurred. Lewis extemporized on the notion of the “Deep Church” in an interview he gave in 1952, rooting the expression he had coined in the works of Augustine, Boethius, Aquinas, the Scriptures, the Great Tradition, and the Rule of Faith, which his successors like Tom Oden, the American Methodist theologian and author of The Rebirth of Orthodoxy: Signs of New Life in Christianity (2003), have christened “Classical Orthodoxy.”

Lewis was completely unaware, of course, that his successors like Andrew Walker and Robin Parry, authors of Deep Church Rising (2014) would argue decades later that the Christian faith needed to cast its eye back to pre-modernity in order to regain the often-forgotten resources that they hope will help secure its future. This was in sharp contrast to the facile and fad-like tenets of the faith currently promulgated by the likes of Justin Welby, the current Archbishop of Canterbury, with all his retro-socialist cant about the evils of the gig economy, welfare policy, the tax system, the insecurity of worker rights, equality, migrants, and Britain’s “broken” social model.

Or, for that matter, Pope Francis, with his habitual open support for migrants, Muslims, and gay people; his stacking of the College of Cardinals in ceremonies at St. Peter’s Basilica with bishops from Africa, Asia, and Latin America; prelates pontificating the poison of Liberation Theology promoted in texts like James Cone’s Black Theology and Black Power (1969), Black Theology of Liberation (1970), and God of the Oppressed (1975), the Peruvian Dominican philosopher, Gustavo Gutierrez, the former Professor of Theology at Notre Dame, with his book A Theology of Liberation (1973), and Robert McAfee Brown’s Liberation Theology (1993).

I suspect that Lewis would have taken serious issue with such corrosive heresy being spoken in the name of the theology he had so readily adopted. His interpretation is more grounded in the works of the Celtic St. Columba, who founded his first monastery in 546 on the site of a sacred Druid grove at Doire Calgach, later called Doire Cholm; St. Dyfrig, a Welsh bishop of Ariconium who lived in the post-Romano British kingdom of Erdig between 425 and 505 AD; St. Augustine’s Mission to convert the English a millennium and a half ago; the 300 or so English Saints of the Old English church celebrated in The Hallowing of England: A Guide to the Saints of old England and their Places of Pilgrimage (1994) — people like St. Felix of East Anglia, St. Edmund, who was martyred in 869, and Edward the Confessor, Anglo-Saxon England’s holy warlord — each of whom are intrinsically part of Britain’s national and spiritual history; and, of course, the early medieval Cistercian abbeys so deeply rooted in our bucolic European landscapes that they form the mason-carved exoskeleton that supports both our sense of place and our fidelity to the faith.

Echoes of this spirituality can still be found in many other epochs, across various geographical climes, and in Christian sects where Western values have and still hold dominion. Some past and current examples include the orthodoxy of faithful White Russians living in Paris after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, with their necropolis in Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois; Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, who founded the German Faith Movement and believed in the notion of Ergriffenheit (being grasped by the sacred); the former evangelical, Lutheran, and Unitarian adherent, Margarete Dierks, who later joined Mathilde Ludendorff’s The German Perception of God; Josemaria Escriva de Balaguer’s Opus Dei, which after initial difficulties flourished under Franco in Spain and is still criticized for being too close to right-wing governments; Dunoyer de Segonzac, Lacroix, Beuve-Mery, and de Lubac’s Knight-Monks of Uriage in Vichy France between 1940 and 1945; and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre’s The Society of Pius X, with its distinctly anti-modernist stance and opposition to the findings of The Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s.

Of course, today, the Socialist-led government in Spain is attempting to ban a Foundation set up in 1976 that defends the memory of Francisco Franco. Still not satisfied with disenfranchising Franco’s memorialists, they also seek to eject the monks from the very abbey that contained Franco’s mausoleum and turn it into a Center of Historical Memory to the Caudillo’s communist and anarchist enemies.

It is a dire and tumultuous situation that is somewhat reflected in Lewis’s close friend Charles Williams’s book War in Heaven (1947), a Holy Grail homage. Lewis comments on his friend’s fiction: “He is writing that sort of book in which we begin by saying, let us suppose that this everyday world were at some point invaded by the marvelous.”

The marvelous, for Lewis, is represented by the splendors of Western Christendom, uncontaminated by the platitudes of social justice warriors and egalitarian obsessives who would strip the very altars of our holy places of their magic and meaning.

In these times of trial and tribulation, Lewis’s words, spoken in 1939 about living a meaningful life during a crisis, have become even more resonant:

Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun. We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [3] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [4] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.