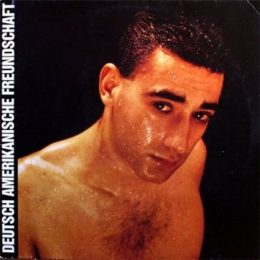

Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft’s Alles ist gut

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 1,349 words

1,349 words

In memory of Gabi Delgado-López (April 18, 1958 — March 22, 2020).

Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft, more concisely known as DAF, is a German electronic music band from Wuppertal consisting of Gabi Delgado-López and Robert Görl. Their name contains a light touch of irony, rendered into English as “German-American Friendship.”

During the band’s heyday, many German (or Germanophone) acts were hitting it big in the mainstream, either in the synthpop or Kraut wave tradition. Several of these groups were also either singing in English or cutting versions of their tracks in English for the American and British markets, like Kraftwerk’s tendency to release albums in multiple tongues, or groups recording English renditions of their chart-toppers as an obvious money grab. Other groups mixed English into their original songs anyways, allowing for some level of crossover appeal; alles klar, Herr Kommisar [1]?

In contrast, DAF recorded all of their original “trilogy” music — the canon records Alles ist gut, Gold und Liebe, and Für Immer — in German, never releasing a single track in English until after a hiatus and their departure from the German spotlight.

Why is this? Let’s ask López [2]:

Whenever we went onstage we never spoke English, we’d say “Guten Abend Mädchen.” We really wanted to bring across our point of view that we were really fighting against English domination of the pop language — it was an important matter to fight that, to not imitate, and to use a language, our own, in which we could truly express ourselves.

Gabi has a point. Living in the West during the Cold War meant a constant bombardment of media from the United States — and to a lesser extent, England — often synonymized with coolness or modernity. The DAF boys were railing against what they saw as a ubiquitous erasure of the culture they know and love, all implicitly or explicitly condoned by the very same people that ostensibly have their best interests at heart.

Wait — two things. One, this sounds awfully reactionary; white people producing art with an explicit focus on maintaining their own culture? And two, the name “López” doesn’t exactly remind me of currywurst. What is going on here?

López is the child of working-class Spanish immigrants to Germany. His identity, of course, is therefore a bit complicated. He learned to speak German at a young enough age for it to be a mother tongue of his, and presumably, most of his childhood memories took place in Germany as well. López, remarkably, doesn’t really show any signs of a debilitating outsider syndrome. This could be chalked up to a few factors with debatable relative importance or veracity:

- Europeans are, in general, similar enough for them to live among each other with minimal conflict.

- López is uniquely adaptable to the culture he grew up in, and is grateful for the opportunities it provided him and his family.

- The politics of the time and place López grew up in profoundly impacted his sense of identity as being German.

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [3]

While the first two are very romantic, the latter seems to carry the most weight when we take DAF’s music into context. Consider, for example, the situation of López’s parents fleeing Franco’s Spain — they were antifascists — only for Gabi to come of age during a time of murder, kidnappings, and hijackings [4] perpetrated by strange kinds of Leftists. He had been thrust into a place on the world stage in which the lines between what was right and wrong in politics had not necessarily been blurred as much as they had been repeatedly crossed, leaving them irrelevant. López “became” German, as it were, because the other option was to either surrender the land that he owed his Ausbildung to to either aggrieved communists or soulless cosmopolitans. It’s a rock and a hard place.

López and Görl took far less of an outward interest in politics, opting instead for a commendable quest to identify the root of the German psyche — and then confront it during an age of national self-flagellation and confusion. There is not a single drop of bitterness to found on Alles ist gut, the record under review, despite its heavy sound, because the DAF boys were channeling not from grievances, but the visceral. Tracks like “Der Mussolini” ultimately contain no messaging other than an acknowledgment that certain things exist — like Hitler, Mussolini, communism, and Jesus Christ. “Der Räuber und der Prinz” works childlike instrumentals into the mix, a nod towards Gabi’s own confused upbringing, and what he presumes may lie unresolved in the heads of Europeans who work under Americanized globalism. “Alle gegen Alle” — covered by Laibach [5] on NATO — brings the mildly self-parodic theme home, with López gnashing about conflict over the top of Görl’s motorik synthesizer sequencing and just-so-slightly awry drumming.

Alles ist gut, in some ways, represents a specific kind of ideal in how art should be produced, which is of special interest to us on the Right. Overt politics in the arts tends to bore, induce cringe, or turn away those who might otherwise be receptive to a message because of its heavy-handedness. When listening to DAF, you can tell that there is an edgy undercurrent involved. Alles’ messaging is left somewhat concealed, however. This is not through deliberate obfuscation, a tactic trotted out by people either ashamed of or uncertain in their beliefs, but through the holistic process of making art that springs from the soul.

The strength of Alles lies in this admirable approach. The compositions on this album are at once simplistic, but never amateurish or lazy. Utilizing only an overdriven Korg, Görl’s kit-smashing, and López’s whipcrack baritone, the group could both provoke and embrace in the space of a three-minute track. That sort of art is infinitely more genuine, and infinitely more valuable, than anything some people in a studio could dream up and show to a boardroom.

Of course, the DAF-Männer were not of our political persuasion, despite some striking synchronicity in the genesis of our respective worldviews. DAF came about in a time where anti-globalism did not have an inherent question of demographics looming over it, for better and for worse. In DAF’s case, it was also couched in the understandable rhetoric of Americo-skepticism, which had a far more visible impact on Western Europe during their tenure as musicians than other problems did — we cannot expect everyone to dig deep at all times. It would also be dishonest not to mention the influence of López’s bisexuality on the group’s aesthetics in both music and performance, with a disquieting fixation on the tropes of muscle, leather, and sweat. Even that, however, is a useful barometer for the group’s honesty. I don’t find it probable that someone would wear a harness as a LARP.

Regardless, the music contained on this record holds immense replay value; Alles is still more than capable of lighting a fire under the feet of the right alternative types today. It was also a highly influential early entry into the genre that came to be known as EBM — “electronic body music” — a style that melds the precision of groups like Kraftwerk with an added emphasis on abrasive rhythm paired with unconventional melodic structures. EBM as a blueprint would inspire groundbreaking acts like Nine Inch Nails, Front 242, Cabaret Voltaire, and many others in the 1980s-90s post-industrial wave that defined crossover heavy music.

All told, Alles ist gut ticks every box on the classic checklist. It manages to be both timeless yet immediately identifiable with an era, influenced dozens of other acts following its release, and contains indisputably remarkable musicianship. I can wholeheartedly recommend it for anyone interested in learning how to dance the Mussolini.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [6] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [7] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.