The Massachusetts Flag & New England’s Indian Wars

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 4,951 words

4,951 words

After the Saintly Sub-Saharan George Floyd (may perpetual light shine upon his blessed soul) died while being arrested, a loud social movement developed to bring down symbols of America’s cultural past — especially America’s white cultural past. The controversy over the Confederate flag is well known, but another controversy exists also — that of the flag of Massachusetts [1].

Vexillology is the term for the study of flags. According to the flag design principles [2] broadly accepted by vexillologists, Massachusetts’s noble banner is inadequate. It is white, which makes dirt and grime noticeable, and it has a seal with lettering which makes it too complex. However, the flag is full of meaning. It is based on the seal of the Massachusetts Bay colony, plus additions made after the Revolutionary War, and it was carried by Massachusetts regiments during the Civil War.

The flag of Massachusetts draws its primary inspiration from the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Indian in the seal is saying “Come over and help us.” It is a reference to Acts 16:9 wherein the Apostle Paul had a vision to preach to Macedonia. Likewise, the Puritans had a vision to convert and help the Indians.

The real reason for the controversy over the Massachusetts flag is non-white resentment over white accomplishment. The most hate-filled complaints from non-whites are specific to the series of Indian Wars which took place in New England.

Before getting too deep into the history of those Indian Wars, it must be mentioned that the contours of the political divisions in the United States have gone from two polite — but opposing — white technocrats insisting that their particular leadership style, judgment, and vision are better to the conflict between Andrew Jackson’s coalition of Yeoman whites vs. Barack Obama’s coalition of non-whites allied with white deviants/spiteful mutants. There is now far less room for compromise and political violence is increasingly common.

Of those offended souls who claim to be descended from New England’s aboriginal tribesmen today, I suspect many aren’t really full-blooded Narragansett or Wampanoag Indians. However, the idea that these disaffected people who claim to be Narragansett and Wampanoag tie into Obama’s alienated non-white coalition holds.

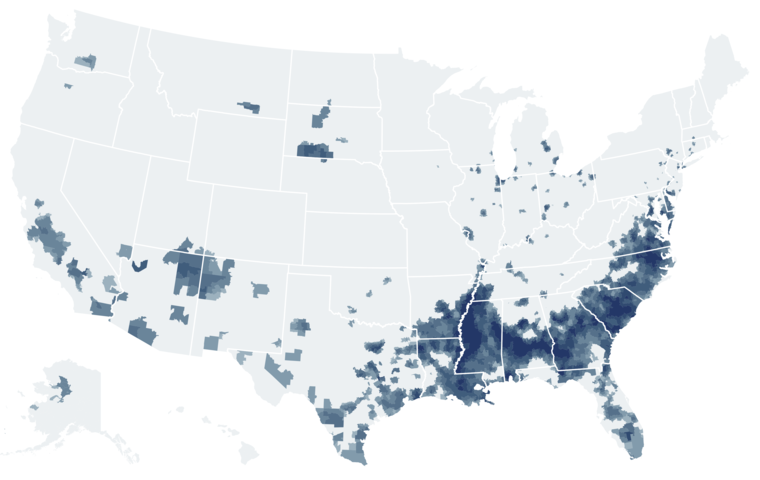

Obama’s Alienated Coalition: This map of the “Extended Black Belt” is from a New York Times article [3] about different TV viewing audiences. It illustrates that blacks and Native American Indians share TV viewing habits. One can presume from this that the two races share a common outlook on other matters, including a deep alienation from American society. Admittedly, Negroes and Indians are vastly different people, but there are some commonalities in crime, vice, etc. in addition to the alienation described above.

The First Storms

Although they didn’t seek out battle, the Mayflower Pilgrims had trouble with the Indians shortly after making landfall at Cape Cod. The first conflict took place on the 8th of December, 1620, at First Encounter Beach. There, a group of Pilgrims and sailors from the Mayflower led by Governor Carver and Captain Standish had a small battle. The English fired their matchlocks and the Red Men loosed arrows. It is certain that no Pilgrims were killed or wounded, and one Indian’s face was splattered by bark when a bullet hit a tree he was standing near.

When the Pilgrims set up their settlement at Plymouth, there were no Indians to deal with there since all but one had perished in an earlier plague. Nonetheless, racial troubles still crept upon the Pilgrims. The first spring after arriving, the Pilgrims made a treaty with Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag Tribe. They also gained a key translator — the famous Squanto. For the next few months, there was always tension, but most of the problems were private jealousies among the Indians that ended up involving Squanto.

The jealousies described above caused the Narragansett to send to the Pilgrims a war challenge in the form of a snakeskin filled with arrows in November 1621. Governor Bradford filled the skin with powder and shot and returned the skin insisting the Pilgrims were ready for peace or war. The Pilgrims fortified and set a watch, but no war came.

The next Indian crisis was sparked by a group of English traders that set up a poorly managed trading post in Wessagussett. The Indians had seen the settlement and noticed weakness, and started planning an attack to destroy all the New Englanders at once. The Pilgrims were saved by two fortunate events. First, Edward Winslow and some others provided medical aid to the Massasoit and other Indians in his village. A grateful Massasoit then informed the Pilgrims of the conspiracy and who, exactly, was leading and organizing it. Then, Phineas Pratt, one of the Wessagussett colonists, fled to Plymouth with news that an attack was imminent thus confirming the earlier report.

Myles Standish assembled a squad-sized element and they traveled by boat to Wessagussett. Once there, he informed the colonists of the danger. He invited Wituwamat and Pekusot, the main conspirators, to lunch where the English jumped them. Wituwamat’s head was taken back to Plymouth and placed on a pole.

Captain Standish brings the head of Wituwamat back to Plymouth. This Indian War is notable in that, only the leading conspirators were killed rather than entire villages, and the critical intelligence needed by the English was gained after an ordinary act of kindness.

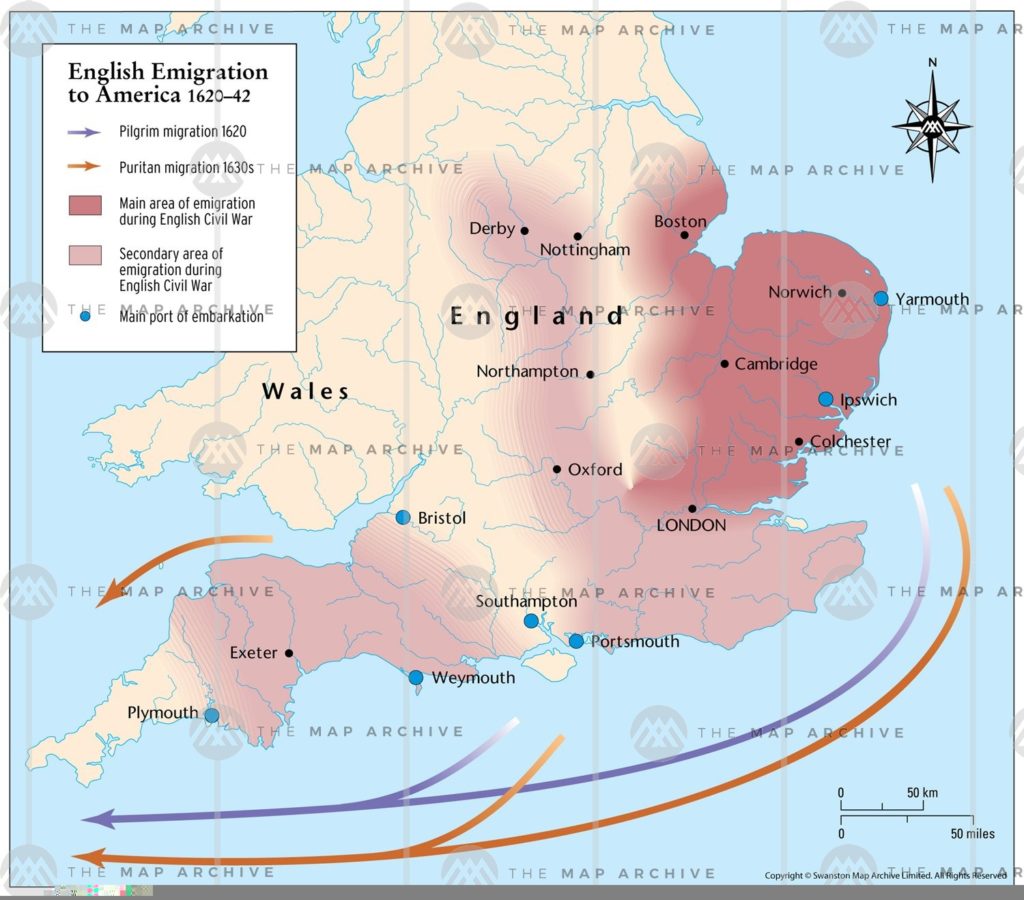

In the decade and a half following the arrival of the Mayflower Pilgrims, more English arrived. This group was mostly from East Anglia and they were nearly all Puritans. They founded Boston and from there spread out to the Connecticut River Valley.

The first settlers of New England were mostly from East Anglia. It is an area that was settled heavily by the Anglos, Saxons, and Danes after the Roman Empire withdrew from Britain.

The Pequot War

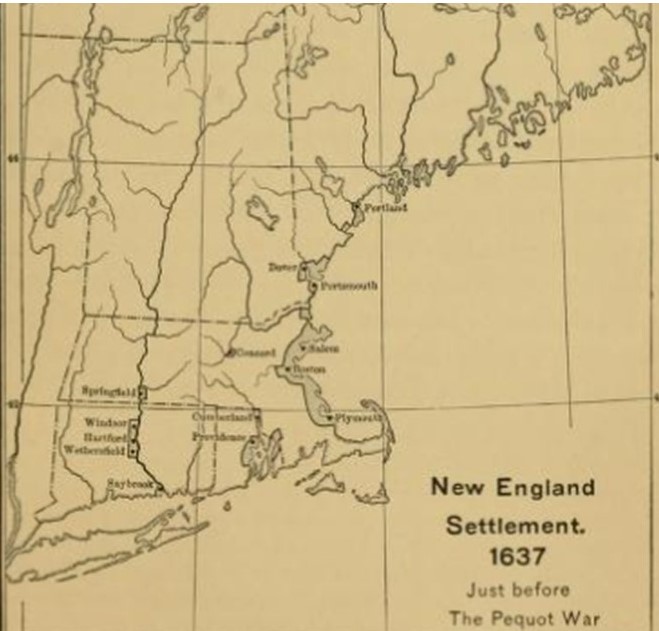

English settlements just prior to the Pequot War. [1] [4]

There is some controversy about the origins of the Pequot. Most accounts, to include the legends of the Pequot themselves, state they were an offshoot of the Mahicans of the Hudson River Valley. More recent linguistic analysis indicates they might be native to Connecticut. Regardless, the Pequot occupied a critical area of the Connecticut River Valley and they conducted trade with the Dutch and English colonists. This trade gave them a technological edge over the other Indians.

The events that led to the Pequot War were related to trade — or more accurately, the murder of traders. After a Pequot was killed by Dutch traders, a group of rogue Pequot killed an English merchant and sailor, Captain John Stone, along with his crew in 1634. The most likely reason for this killing was a Pequot tradition where a family could avenge the murder of a relative. Captain Stone and his crew were killed to avenge the aforementioned killing of a Pequot by the Dutch.

Captain Stone was something of a rogue himself. He had done privateering in the West Indies and landed in trouble with the Puritan authorities earlier, but the English demanded compensation for the murders from the Pequot.

Talks over the death of Captain Stone broke down. The English launched an ineffective raid against the Pequot on Block Island in August 1636. For the next few months, the Pequot would rage up and down the Connecticut River Valley attacking the English. White captives were tortured to death by the Pequot, Fort Saybrook was under siege on and off, and Wethersfield, Connecticut was attacked. Two English girls were taken prisoner and several adults were killed. (The girls were later ransomed.) Meanwhile, both the Pequot and English attempted to get the Narragansett on their side.

Eventually, the three Puritan Colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, and Connecticut decide to carry out a united policy. They focused on an attack upon the Pequot center of gravity — their fortification at Mystic, Connecticut. In late May 1637, the English, Narragansett, and other allied tribes formed a battalion and moved on the Pequot fortification.

The English and their Indian allies attacked at dawn and the fortress was burned to the ground along with many Pequot, including women and children. The English made a fighting withdrawal from the area. The rest of the conflict is anti-climactic. The English and their allies captured or killed Pequot until a one-sided treaty was signed in Hartford.

Almost all modern accounts of this conflict blame the English and condemn the heavy-handed way in which they waged war, but in their defense, I offer the following:

- The English in Virginia had already attempted a multiculturalist, soft-touch approach with the tribes. This invited a massive attack in 1622. This event was known to the English in New England and colored their outlook.

- The English and Dutch were trading with Indians up and down the East Coast with little violence. Trade with the Pequot was unique in how many corpses it produced.

- While the murder of Captain Stone and his crew were within Pequot traditions, those traditions were unjust.

- Nature is red in tooth and claw. Once war starts, the idea is to win. If the opportunity comes to burn your enemy in their huts to achieve victory, take it. Furthermore, had the English showed themselves to be easy pickings against the Pequot, it is certain that other Indians tribes would have made trouble.

- It is also likely that the Pequot didn’t really understand what they were getting into. They carried out threats and violence with little understanding of the likely consequences.

Roger Williams

As the events with the Pequot played out, Roger Williams, a Puritan minister, started his extraordinary career. Williams was out of step with most of the Puritan religious leaders of the colony. Today, most of the nuance of his theological differences with the Boston Puritan authorities can only be understood by scholars of seventeenth-century Protestantism. The big differences are easy to understand, though. Williams believed in freedom of consciousness and the separation of civil government from religious government.

In 1636, with several families of followers from Salem, Massachusetts, Williams founded Providence, Rhode Island after gaining title to the land from two Narragansett Indian chiefs. Rhode Island thus became the place for Puritans that didn’t fit in, to include dissenters with a coherent ideological and philosophical theology as well as a collection of people that are difficult to manage in any circumstance. Meanwhile, Williams became a supporter, to a degree, of upholding Narragansett rights against the English.

It wasn’t so much that Williams was actively supporting Narragansett Indians murdering whites. It was that he created a government that was uncooperative with the other white governments of New England. As a result, the racial politics between the English and the various Indian tribes — as well between the tribes — had more complexity than what otherwise could have been.

King Philip’s War

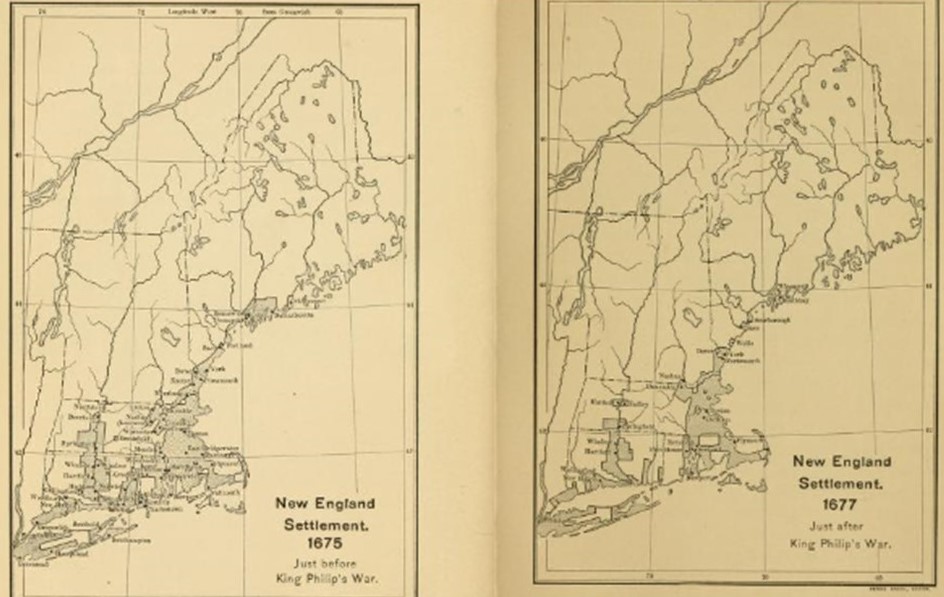

The definitive account of King Philp’s War is probably the book Flintlock & Tomahawk (1958) by Douglas Edward Leach. In it, Leach says the first white victims of the war in Swansea, Plymouth Colony were “. . . living almost under the very shadows of their enemies.” [2] [5]

King Philp’s War is the bloodiest conflict per capita in American history. The whole of New England’s white society was affected by the conflict. If one has any ancestors who are of New England’s founding stock, then it is certain that one has ancestors in the conflict.

While there was plenty of warning that such a war was about to occur, the war still took the colonial authorities by surprise. Indeed, the main Indian belligerents in the conflict were the oldest Indian allies of the English — the Wampanoag. The Wampanoag were related to most of the other Indian tribes in southern New England and they spoke the Massachusett language. [3] [6]

The distribution of the Massachusett language speakers prior to the arrival of the Pilgrims. [4] [7]

Using first-hand sources, Vaughan shows that the Puritans were not indifferent to Indian territorial claims or other sensitivities. Purchases of land were managed by the respective colonial governments so that swindles were kept to a minimum. The English even insisted upon Indian jurors in court cases involving Indians. From the end of the Pequot War until King Philip’s War, there were fifty years of peace.

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [8]

As with all conflicts involving non-whites attacking whites, King Philp’s War probably started before the English realized it. The first inkling that something was up occurred in January 1675 when John Sassamon was killed by agents of the Wampanoag Chief “King Philip.” Sassamond was a Christian convert, a “Praying Indian,” who’d worked as an advisor to Philip. Sassamon’s murderers were tried, convicted, and hanged, but Sassamon’s warning went unheeded. In the following months, English visitors to Wampanoag villages noticed braves in war paint and other acts of non-lethal aggression. In the days preceding the war, young Wampanoag men went on a rampage of looting and arson on a number of isolated English farmsteads.

The Wampanoag military consisted of every able-bodied male. They were warriors though, not soldiers. This critical difference will be explored later. In the long years of peace, the Wampanoag and other Indians had acquired the latest in weaponry, the flintlock.

The English military was organized in a way that matched the cultural sensitivities of the Puritans of East Anglia. Every male in the town from the age of sixteen to sixty was in the militia. Each man was part of a company which was part of the town’s trainband. The trainband was organized for defense. For offensive operations, a composite company would be created from men in the trainband. [5] [9]

Militia training prior to the outbreak of King Philp’s War consisted of drill on the town common. The men were equipped with matchlock muskets and pikes. They were less trained than any soldier that has graduated from basic in modern times. They had no knowledge of ranger tactics or counter-insurgency operations. Initially, the English were outgunned by the Indians with flintlocks. The only two advantages some of the English had were steel breastplates, helmets, and swords. The armor protected the wearer from blows of a club, thrusts from a knife, or arrows, but not a well-aimed shot from a flintlock. In the age of single-shot muzzleloaders, swords still came in handy and the English were usually armed with a cutlass.

In the event of an Indian attack, the whites would retreat to a garrison house. A garrison house would fit neatly on the street of any suburb in America today, and it was often in the traditional New England “saltbox” style; which originated in the traditional building forms of East Anglia [10]. The men of the militia would mount a guard in the militia house and the women and children would stay within the house. The personal dynamics in such a house during times of stress were less than ideal. The women bickered, the children fought, men grumbled. But on the whole, garrison houses were decent fortresses against Indian attacks.

It is likely that King Philp’s War was not started on a set of specific orders or war plans drawn up by the Wampanoag Chief. Instead, the conflict was started by the young men of the tribe rampaging through white farmsteads. King Philip was probably forced to follow their lead.

Regardless of exactly who gave what order to kick off the war, it is certain that the Wampanoag attacked the English settlement at Swansea on June 20, 1675. The English called out the militia, moved to Swansea, and then attacked and conquered the Wampanoag territory at Mount Hope in Rhode Island. After capturing Mount Hope, the English assumed the Wampanoag would return, so they built and manned a fort to deal with such a contingency. However, the Wampanoag had escaped to the Pocasset Swamp prior to the English attack.

The enemy slipped away, making the war longer and bloodier. It is not unreasonable to compare the Wampanoag escape to Osama bin Laden’s escape from Tora Bora, Afghanistan in 2001.

After a considerable delay, the English attempted to destroy the Wampanoag in the Pocasset Swamp in July, but the terrain and lack of training and experience on the part of the English soldiers allowed the Wampanoag to escape northwards. King Philip — or the anti-white idea of King Philip — caused a great many Indian tribes to launch attacks upon English settlements across New England. From September 1675 until late spring the next year, the whites of New England suffered burned towns, defeat in battle, and many setbacks.

The best account of the conflict from a civilian’s point of view is Mrs. Mary Rawlandson’s book, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God (1682). After the Indians overran her garrison house in Lancaster, Massachusetts, she wrote:

I had often before this said that if the Indians should come, I should chuse rather to be killed by them, than taken alive: but when it came to the trial, my mind changed; their glittering weapons so daunted my spirit that I chose rather to go along with those) as I may say) ravenous bears, than that moment to end my days. [6] [11]

While Philip was rampaging across New England, the English political leadership had to get along. The three Puritan colonies — Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut — were known as the United Colonies. For the most part, they coordinated their operations smoothly. Rhode Island was made up of English Protestants who were dissenters from Puritanism as well as Quakers, but they did share the common English regional heritage with those in Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut. Rhode Island was neutral in the technical sense, but provided assistance to the forces of the Puritan United Colonies enough that one could say they were really active participants. Relations with the Colony of New York, led by Edmund Andros, was bad. As King Philip’s warriors burned Swansea, the Connecticut militia had to deploy to deter Andros’s soldiers from annexing Connecticut Territory. Andros provided some aid to the New Englanders, but on the whole, New York did little.

The various Massachusett-speaking Indian tribes were horribly divided. There were Indian tribes that were hostile to the Wampanoags or their allies, especially in Connecticut. There were also the Praying Indians. These were Indian converts to Puritan Christianity. Then there were Friendly Indians, which were non-hostile heathens.

While these Indians were hostile to the Wampanoags, both types of Indians were a mixed bag to the New Englanders. There are accounts of various Praying Indians attacking individual whites out of the blue, and friendly Indians suddenly turning violent as a group and burning an English settlement. The Praying Indians were eventually interred on Deer Island.

Eventually, the exact policy of waging war upon the Indians fell between two poles. One pole was a school of thought propagated by Captain Samuel Moseley. To put it simply, Moseley killed any Indian he found no matter what their supposed loyalty was and burned their crops and villages. (Note: New Englanders didn’t do that until after the war started and stopped when it ended.) The second pole was based on ideas pioneered by Captain Benjamin Church. That is to say, Church enlisted friendly Indians — both Praying and Heathen — into his company. The company would take to the forest, kill the hostiles, and provide amnesty for those who surrendered.

As the war continued and hearts hardened, ordinary English soldiers would put to the sword any Indian they came across. Indian crops and food stores were also burned when discovered by any English soldiers. Eventually, Connecticut’s Major John Talcott enacted a policy where captured Indians would be sold into slavery. Philip’s Indians would be sold in North Africa and the West Indies. They weren’t good slaves, though, and eventually, Jamaica and Barbados legislated against admitting these Indians at all.

There are two important blows the English inflicted that turned things around. The first was in December 1675. After months of debate, the United Colonies’ respective governments had determined the Narragansett were not neutral and would likely enter the war on King Philip’s side in the spring. The evidence for this is pretty sound. The Narragansett were treating injured Wampanoag, they rejoiced in hearing of Indian victories, and it was probably Narragansett warriors that were unofficially campaigning with King Philip. Thus, the Puritan colonies assembled a large force and they attacked and burned the Narragansett fortification after a tough mid-winter march. The Narragansett were knocked out of the war in a single action.

The next blow came when experienced militiamen saw an opportunity. In May 1676, Captain William Turner positioned in Hatfield, Massachusetts got word of a large group of Indians focused on catching and drying fish. Turner led a company plus sized element to the Indian location and attacked. Eventually, the Indians rallied and Turner was forced to conduct a fighting retreat, but hundreds of Indians had been killed.

The cumulative efforts of the English broke Indian resistance. Warriors began to surrender, and as it became clear that the war was winding down, the Colonial governments started to offer amnesties. King Philip’s family was captured by Captain Church and sold into slavery. King Philip was killed on 12 August 1676 by one of Church’s Indian soldiers. Afterward, there were sporadic operations in Maine, and an Indian raid in the Connecticut River Valley in 1677, but King Philip’s death effectively ended the conflict.

King Philip’s War severely set back New England’s settlements and economy. Conditions were close to famine at the height of the war. The New Englanders paid for the conflict in various ways, with raising taxes as the primary method. The Colony Taxes in Dorchester went from £28 in 1671 to £408 in 1675 and were still high at £111 in 1678. [7] [12]

Indians as an organized group remained a serious threat to American whites well into the 1890s, but after they were put on reservations and pacified, whites started to take a romantic view of them. However, a look at King Philip’s actions show that the Indians were reckless murderers led by a man with poor strategic instincts.

The first thing one notices is that King Philip was forced to abandon his capital territory days after launching his war. Such an action is an indicator of a bad plan, if a plan even existed at all. The retreat to the swamp made his people dangerous, but also desperate. It was only a matter of time — fourteen months, in fact — before Philip’s followers would be in a position to be destroyed while they were gathering food at a location known to every Englishman in the area. Second, King Philip had no idea what victory would look like. He had no list of demands and made no effort toward a diplomatic alliance with the French. He also attacked all whites regardless of their station in society, including potential sympathizers among the English at Providence. The conflict was that of Indians lashing out in a childish, murderous rage.

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [13]

During the conflict, New England’s Puritans held special days of humiliation and prayer and searched their souls for the deeper reasons for the calamity. They found blame in nearly every nook and cranny of their society and worked to correct it. The Indians did no self-correction or self-reflection that was ever recorded. Today, the alleged Wampanoag and other tribesmen in New England carry out a moral swindle where they seek financial gain for harms they did not experience from people who have done no harm.

Additionally, King Philip’s army were warriors, not soldiers. This distinction is critical. While the Indian warriors were better in the field than the English at the outset of the war, they never improved or broadcast lessons learned throughout their force. It should be noted that Mrs. Mary Rowlandson’s garrison house was the only garrison in Lancaster that fell on the day of the attack; the rest held. On the whole, the Indians never really learned how to take down such a compound.

The English soldiers held their ground, understood their place in the system, their length of service, etc. Information regarding what worked and what didn’t work was transmitted across New England’s army. An English soldier was expected to serve until his enlistment was up, but when it was up, that soldier returned to his normal life. The Indian warrior served for life; if they felt like it. King Philip’s braves often took a hike when things got tough.

Politically, the English were also at a big advantage. The political councils were places of disagreements and arguments, but the English politicians from Massachusetts didn’t stab the politicians from Connecticut after a disagreement. They put the matter to motions, seconded the motions, voted, and made the recommendations. The loser’s ideas in such an event could still get picked up later and there was no blood feud. Meanwhile, King Philip was betrayed by a man who was a relative to someone King Philip murdered in a dispute over strategy.

However, King Philp’s mentality is not all that different from other parts of the non-white world. The resentment-filled terror group ISIS was not unlike the Wampanoag in 1675.

Outside of the fact that King Philip launched a sneak attack, one of the causes of the conflict is an Anglo-Saxon trait that Americans — and indeed, all other Anglos — need to recognize and remember. Walter Russell Mead writes:

The Anglo-American order and the liberal capitalism it brings have been the harbingers of failure, marginalization, defeat, and frustration for much of the world. Like beavers, the Anglophones have been building a dam; as the dam rises and the pond grows, the beavers see a world that is getting better and better. They see plenty of food, security for all. But not all the animals are happy. There are some who manage well enough, the fish and the salamanders and perhaps the raccoons, but the squirrels, red and black, are not thrilled about the destruction of trees; the rabbits lose their nests and the foxes their dens. [8] [14]

The Wampanoag were losing their way of life. But they failed to adapt and missed big opportunities. The Wampanoags were on some of the most valuable territories in New England and had a clear title to the land. They could have built docks and lived well of the tariff revenues from the shipping. They didn’t need to go to war. However, they never seemed to recognize their advantages. Their den got flooded.

There are other non-whites out there who see their way of life being destroyed by our daily economic actions. For example, there are no American Negroes that really fit in the Anglo economic system since the end of slavery in any place other than on the bread lines. Thus, they are filled with resentment. And while they will not be able to come up with a plan for victory, they can make life for us difficult to impossible in the short term. It is well for us to study the ideas and tactics of Captains Moseley and Church.

With that in mind, there is no flag of any type in the United States today that will be free of any symbols of so-called “White Oppression.” Every state militia has fought Indians or other non-whites. Even if every flag is changed, police wearing the patch of the new banner will be arresting non-whites and the cycle of non-white-caused flag-switching will start again.

So, the flag of Massachusetts. Long may it wave.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [15] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [16] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [17] Louis Kimball Mathews, The Expansion of New England: The Spread of New England Settlement and Institutions to the Mississippi River, 1620-1865. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909, p. 22.

[2] [18] Douglas Edward Leach, Flintlock & Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press, 2009 (1958), p. 35.

[3] [19] The Massachusett language is well-documented [20], and there remain speakers of the tongue today — although they are few in number.

[4] [21] Adapted to English by Hydrargyrum from the original, Wikimedia Commons.

[5] [22] In his book, A Rabble in Arms: Massachusetts Towns and Militiamen during King Philip’s War (2009), Kyle F. Zelner gives a good account of the social and demographic circumstances of the men who served, especially from Essex County, Massachusetts. In his 1896 classic, Solders in King Philip’s War, George Madison Bodge documents every soldier in the conflict to include the Companies they were in, the battles those Companies participated in, and how much each man was paid. The latter book is a goldmine for genealogists.

[6] [23] Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity, Sufferings, and Removes, of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson: Who was Taken Prisoner by the Indians; with Several Others. . . Written by Her Own Hand [24]. Cornhill: Thomas and John Fleet, 1856 (Digitized 2007, Harvard), p. 10.

[7] [25] Mathews, The Expansion of New England. pp. 85-86.

[8] [26] Walter Russell Mead, God and Gold: Britain, America, and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Random House, 2007, p. 328.