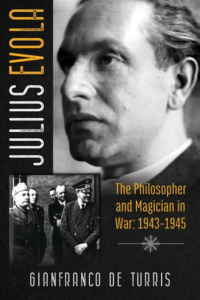

Julius Evola: The Philosopher & Magician in War: 1943-1945

Collin Cleary3,484 words

Czech version here

Gianfranco de Turris

Julius Evola: The Philosopher and Magician in War: 1943–1945

Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2020

This English translation of Gianfranco de Turris’s Julius Evola: Un filosofo in guerra 1943–1945 has come along at just the right time, for it shows us how a great man coped both with societal collapse and with personal tragedy. As the title implies, the book focuses on Evola’s activities during the last two years of the Second World War. However, de Turris goes considerably beyond that time frame, dealing with much that happened to Evola after the war, up until about 1950.

De Turris’s main objectives in this work are to solve a number of mysteries about Evola’s activities at the end of the war, and in the post-war years, and to respond to the philosopher’s critics. Because, until now, so little has been known about these years in Evola’s life, they have been the object of a great deal of speculation, especially on the part of hostile, Left-wing writers. De Turris has uncovered fascinating new information about Evola’s activities and provided definitive answers to a great many lingering questions.

The book begins with an episode that will doubtless be the focus of most critical reviews: Evola’s journey to Hitler’s headquarters in August–September 1943. As the war dragged on, public opinion in Italy had begun to turn against Mussolini, especially after Rome was bombed by the Allies for the first time on the 19th of July. Several members of the government had turned against Mussolini, and the Duce felt compelled to summon the Fascist Grand Council for the first time since the beginning of the war. This turned out to be a mistake, for it passed a motion of no confidence in Mussolini, effectively giving King Victor Emmanuel the power to dismiss him. Mussolini, however, behaved as if nothing of significance had occurred. He appeared for an audience at the royal palace the next day, prepared to brief the King on recent events. Instead, the King had Mussolini arrested and imprisoned in a hotel atop Gran Sasso mountain, the highest peak in the Apennines.

The story of Mussolini’s daring rescue (on the 12th of September) by German commandos flying gliders, led by the legendary Otto Skorzeny, is one of the most famous episodes of the war. Mussolini was immediately flown to Munich and then to Hitler’s HQ (“Wolf’s Lair”) in East Prussia. When he arrived on the 14th of September, Julius Evola had already been there for several days. The philosopher was part of a delegation chosen by the Germans to help advise them on what course to take in Italy. The delegation also included the Duce’s son, Vittorio.

Their journey from Italy was undertaken at considerable risk. The plane carrying Evola narrowly escaped interception by Allied aircraft. On the ground, Evola and others were disguised for part of their journey in Waffen SS caps and coats. Once the philosopher had arrived at Wolf’s Lair, he and the other members of the delegation were received by Joachim von Ribbentrop who communicated to them Hitler’s wish that “the Fascists who remained faithful to their belief and to the Duce were to immediately initiate an appeal to the Italian people announcing the constitution of a counter-government that confirmed loyalty to the Axis according to the commitment first declared and then not maintained by the King” (quoting Evola’s account, p. 20).

Believe it or not, this is one of the less interesting parts of de Turris’s book. Far more interesting is what happens to Evola later. Those already familiar with the details of Evola’s life will know what is coming: his flight from Rome, his injury in Vienna, and his long recovery in the years immediately following the war. This part of the book is more interesting not just because it fills in many blanks in Evola’s biography, but because it reveals a more “human” side to the philosopher. I apologize if this seems a somewhat maudlin way to speak of a man like Evola, but I can think of no alternative.

Those who have read Evola extensively know that the philosopher can often seem as remote as the peaks he climbed in his youth. In de Turris’s account, however, we find an Evola who is initially depressed and dispirited by the outcome of the war, and by his injury. He struggles to make sense out of why these things have occurred, and he struggles to define what his mission must be in the post-war situation. Eventually, he emerges triumphant, but it is instructive to see not only how he overcomes his struggles, but that he struggles. In facing our current situation, in which the Western world (especially the US) seems to be falling down around our ears, Evola’s example gives us strength. We see that even Evola, even this “differentiated type” (to use his terminology) had to struggle with adversity — but that he overcame.

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here.

On June 4, 1944, the Allies captured Rome. One of the first things their agents did, just hours after entering the city, was to pay Julius Evola a call. Allied intelligence had learned that Evola’s name was on a list of intended agents of a German-led “Post-Occupational Network” for espionage and sabotage (his codename was “Maria”). They showed up at Evola’s apartment, no doubt with the intention of arresting and interrogating him. However, Evola’s elderly mother detained them at the entrance, while the philosopher slipped unnoticed out a side door. The one thing he took with him was a suitcase containing the materials that would eventually become the three-volume Introduction to Magic (Introduzione alla magia).

Evola then embarked on a long and arduous journey. On foot, he made his way out of the city and located the retreating German troops. They gave him shelter, and eventually, he wound up in Vienna, where he lived under an assumed name. Exactly why Evola headed for Vienna has been something of a mystery, and de Turris spends a good deal of time on it. Incredibly, it appears that Evola went to Vienna to undertake research on Freemasonry at the request of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst; the “Security Service” of the SS)! The SD’s “Office VII” had been engaged in Freemasonic studies, and they were not going to interrupt it for a small thing like the apocalypse.

Evola later told an associate that the SD had assigned him the task of “a purification work and ‘return to the origin’ of the Freemasonic rituals found during the war by the German troops in various countries” (p. 158). Evola was not sure exactly why the SD was interested in this. Had they sent him in search of the Ark of the Covenant, it would hardly be more surprising. In case it is not obvious what Freemasonry had to be “purified” of, Evola actually makes this clear in his autobiography The Path of Cinnabar (Il cammino del cinabro): “[Freemasonry] initially had an initiatic character but later, in parallel with its politicization, had moved to obey and subject itself to anti-traditional influences. The final outcome was to act out the part as one of the main secret forces of world subversion, even before the French Revolution, and then in general solidarity with the revolution of the Third State [sic]” (quoted in de Turris, p. 159; The translator means “Third Estate,” which, in the French Ancien Régime, was made up of the peasants and bourgeoisie).

On January 21, 1945, Evola decided to take a walk through the streets of Vienna during an aerial bombardment by the Americans (and not the Soviets, as has been erroneously claimed). While he was in the vicinity of Schwarzenbergplatz, a bomb fell nearby, throwing Evola several feet and knocking him unconscious. He was found and taken to a military hospital. When the philosopher awoke hours later, the first thing he did was to ask what had become of his monocle. Once the doctors had finished looking him over, the news was not good. Evola was found to have a contusion of the spinal cord which left him with complete paralysis from the waist down. As Mircea Eliade notoriously said, the injury was roughly at the level of “the third chakra.” It resulted in Evola being categorized as a “100-percent war invalid,” which afforded him the small pension he received for the rest of his life.

Why did Evola go for a walk during a bombing raid? Eliade erroneously claimed that Evola “went to fight on the barricades against the Soviet Russian advance on Vienna” (p. 128). Evola provides an answer himself, in a hitherto unpublished letter to the wife of the Austrian conservative philosopher Othmar Spann:

. . . I would always challenge destiny, so to speak. And from here originate my acts of folly on the glaciers and mountains: hence the principle of my not caring or having any concern about the aerial bombardments. And the same goes for when I was in Vienna when the situation had exacerbated to the point of severe danger. . . . In the end I was caught by a carpet bombing in Schwarzenberg. [p. 125]

But when Evola went out walking that fateful day, he had expected that his destiny would be either to live or to die. He was not expecting that he might be destined to live out the rest of his days as a cripple. This turn of events seems to have utterly perplexed the philosopher, and he struggled to make sense of why this had happened to him, and at that point in his life. Matters were complicated by Evola’s belief, stated years later in The Path of Cinnabar, that “there is no significant event in existence that was not wanted by us before birth” (quoted in de Turris, p. 169).

In the same letter to Erika Spann, Evola writes: “What is not clear to me is the purpose of the whole thing: I had in fact the idea — the belief if you want to call it, naïve — that one either dies or reawakens. The meaning of what has happened to me is one of confusion: neither one nor the other motive” (p. 170). De Turris refers to the “incomprehension and disillusionment” Evola experienced “at the outcome and aftermath of the war” (p. 54). The philosopher had been struggling to understand the cataclysm that had engulfed Europe and destroyed Fascism and National Socialism, concerning which he had cautiously nurtured certain hopes. Now, additionally, he had to make sense of why fate had chosen to permanently cripple this Western kshatriya, this man of action. It is difficult to imagine the desolation and inner turmoil Evola had to endure in the years immediately following the war. Again quoting the letter to Frau Spann: “In this world today — in this world of ruins — I have nothing to do or look for. Even if tomorrow everything magically returns to its place, I would be here without a goal in life, empty. All the more so in this condition and in this clinic” (pp. 199-200).

Evola was eventually transferred to a hospital in Bad Ischl, where he received better treatment. De Turris offers a rather harrowing account of the various operations and therapies used to treat Evola, mostly without success. Despite his condition, while at Bad Ischl, Evola actually traveled to Budapest, where he remained for a couple of months before returning to Austria. Little is known about what Evola was doing in Budapest or who helped him get there (though we now know the address at which he was living). De Turris argues persuasively that Evola went there to be treated by the famous Hungarian neurologist, András Pető, who had some success in the treatment of paralysis using unconventional methods. Unfortunately, he was not able to help Evola.

From the beginning, Evola had entertained the possibility that his paralysis was “psychic” in nature. He was encouraged in this belief by René Guénon, with whom he continued to correspond from his hospital bed in Bad Ischl. Guénon wrote to him:

According to what you tell me, it would seem that what really prevents you from recovering is more of a psychic nature than physical; if this is so the only solution without doubt would be to provoke a contrary reaction that comes forth from your own self. . . . Besides, it isn’t at all impossible that something might have taken advantage of the opportunity provided by the lesion to act against you; but it’s not at all clear by whom and why this may have occurred. [p. 148]

In fact, there does seem to be something mysterious about Evola’s condition. In 1952, he was visited in his apartment by several associates, including the anthroposophists Massimo Scaligero and Giovanni Colazza. During this visit, the men saw Evola move his legs – something that, given his paralysis, should have been completely impossible. After leaving Evola’s presence, they were naturally eager to discuss this. It was reported that Colazza said to Scaligero, “Of course he could! But he doesn’t! He does not want to do it” (p. 197).

You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune?, featuring extensive discussions of Heidegger, here

Setting this mystery aside, Evola appears to have become reconciled to his condition by reminding himself that, after all, the body is but a temporary vehicle for the spirit. In a letter to a friend, he states that “in regard to my situation — even if I had to remain forever like this, which is not excluded — it spiritually does not signify anything more for me than if my car had a flat tire” (p. 168). Another friend, a Catholic priest, naïvely suggested that Evola travel to Lourdes in hopes of a miracle cure at the Sanctuary of our Lady. Evola responded with kindness and patience, saying, “I have already told you how little this thing means to me . . . The basic premise, which is that of an ardent desire for a healing, is first of all lacking. If grace were to be asked for, it would rather be to understand the spiritual meaning as to why this has happened — whether it remains this way or not; even more so, to understand the reason for my continuing to live” (pp. 168-69).

And, in time, Evola does seem to have come to some understanding of why fate had dealt him this hand, though he never made public these very personal reflections. On the eve of the philosopher’s return to Italy in August 1948, his doctor at Bad Ischl reported that “the general state of the patient has improved considerably in these last days, the initial depressions have become lighter, the irascibility and the problems of relationship with the nursing staff and patients have declined markedly” (p. 176). Indeed, one imagines that Evola was not an ideal patient. He wrote to Erika Spann of the “spirit-infested atmosphere of the diseases of these patients” (p. 193; italics in original).

What undoubtedly lifted Evola’s spirits is that he had at last defined what was to be his post-war mission. In The Path of Cinnabar, he writes that

The movement in the post-war period should have taken the form of a party and performed a function analogous to that which the Italian Social Movement [MSI] had conceived for itself, but with a more precise traditional orientation, belonging to the Right, without unilateral references to Fascism and with a precise discrimination between the positive aspects of Fascism and the negative ones. [Quoted in de Turris, p. 54]

Concerning this, de Turris comments that “all of his [post-war] publishing activities and book-writing projects were specifically oriented in this direction” (p. 54). In 1949, Evola began writing again, initially under the penname “Arthos.” He wrote in bed, in pencil, with a lap desk placed before him, or he used a typewriter, seated at his desk in front of the window. His French biographer, Jean-Paul Lippi, referred to him as “an immobile warrior.”

Around this time, Evola learned that he had become an idol of Right-wing youth in Italy. In September 1950, he addressed the National Youth Assembly of the MSI in Bologna. The inclusion of Evola seems to have been last-minute. The organizers heard that the philosopher was staying at a nearby hospital and paid him an impromptu visit. One of the men present offers this moving account of what happened next:

We introduced ourselves and invited him to attend the assembly. He made himself immediately available and expressed great interest. He asked us if he could have the time only to change and shave. I remember that in his haste he had a small cut on his cheek. We carried him in our arms and placed him in the German military truck. Upon entering the assembly hall he was warmly welcomed by our group and since Evola was unknown to me as a thinker, Enzo Erra introduced him as a heroic invalid of the Italian Social Republic. On stage, while I was supporting him, I noticed that he was pleasantly surprised and moved by the welcome of hundreds of young people. He silently fixed his attention and listened intently to the various interventions, and at the end of the proceedings we took him back to the hospital. It was at that moment that we had the idea of asking him to write a booklet that would be a guide, and that was how the Orientamenti was born. The next day we accompanied him to a small mountain hotel in the Apennines. [p. 207]

Julius Evola was back. Indeed, he wrote some of his most important books in the post-war years: Men Among the Ruins, The Metaphysics of Sex, Ride the Tiger, The Path of Cinnabar, Meditations on the Peaks, and others. Arguably, he enjoyed far more influence after the war than he ever did before. Disturbed by his influence on the youth, Italian authorities arrested Evola in May 1951 and put him on trial for “glorifying Fascism.” He was acquitted — something that would be unimaginable in today’s world, given its unironic concern with “social justice.”

This book is required reading for admirers of Evola, and students of traditionalism generally. It should also be read by Leftist critics of Evola — though it will not be, or, if it is, the contents will be distorted and misrepresented. You see, de Turris does almost too thorough a job of demolishing Evola’s detractors. One wishes, in fact, that he had spent a little less time jousting with these people, as they all come off as dishonest lightweights. Still, I suppose it is necessary. And “jousting” is an appropriate term, as de Turris’s defense of his mentor is gallant and virile in the best tradition of the “aristocrats of the soul.” He has learned from a master, and in his voice we sometimes hear an echo of Evola’s own. De Turris is well-qualified to tell Evola’s story: he knew the philosopher personally, and is the executor of his estate.

Among the fine features of this volume are two interesting appendices. The first consists of illustrations, some of which are fascinating. One is a reproduction of the top of a cigar box signed by the men present at Wolf’s Lair, including Evola, Vittorio Mussolini, and others. The second appendix consists of hitherto-unpublished translations of several articles Evola wrote in 1943 for La Stampa, the daily newspaper in Turin. I will close with a quote from one of these, which is not only prescient, given Evola’s fate after 1943, but also particularly relevant to the situation in which we now find ourselves:

From one day to another, and even from one hour to another, an individual can lose his home to a bombardment: that which has been loved the most and to which one was most attached, the very object of one’s most spontaneous feelings. . . . It has become blatantly clear . . . as a living fact accompanied with a feeling of liberation: all that is destructive and tragic can have value to inspire. This is not about sensitivity or badly understood Stoicism. Quite the contrary: it is a question of knowing and nurturing a sense of detachment from oneself, people, and things, which should instill calm, unparalleled security, and even . . . indomitability. . . . A radical breakdown of the “bourgeois” that exists in every person is possible in these devastating times. . . . [To] make once more essential and important what should always be in a normal existence: the relationship between life and more than life . . . During these hours of trials and tribulations the discovery of the path, where these values are positively experienced and translated into pure strength for as many people as possible, is undoubtedly one of the main tasks of the political-spiritual elite of our nation. [pp. 261–62]

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Julius%20Evola%3A%20The%20Philosopher%20and%23038%3B%20Magician%20in%20War%3A%201943-1945

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Nowej Prawicy przeciw Starej Prawicy: Przedmowa

-

Stalin’s Affirmative Action Policy

-

Notes on Plato’s Alcibiades I Part 1

-

Sperging the Second World War: A Response to Travis LeBlanc

-

Doxed: The Political Lynching of a Southern Cop

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 2

-

On Second World War Fetishism

-

James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Part 1

9 comments

All this came as a great surprise to me.

I chuckled at this:

“From the beginning, Evola had entertained the possibility that his paralysis was “psychic” in nature. He was encouraged in this belief by René Guénon, with whom he continued to correspond from his hospital bed in Bad Ischl. Guénon wrote to him:”

It is funny how testimony consistently portrays Guenon as something of a kooky, superstitious hermit, always watchful of some sinister conspiracy. Refer to those letters to Evola in which he explains his reasons for refusing to take photos.

I have not read anything by Evola.

Any advice on which of his books should I read to get the essence of his idea’s (i.e. under the assumption that I would not read anything else by him)

You should read “Revolt Against the Modern World.”

Thanks, I’ll have a look at that.

Just bought the book, wonderful. But taking one glance at the front cover photo, and to me it is very obvious that the person in the background is not Julius Evola but actually Werner Naumann.

Articles like this are why I keep coming back to Counter Currents. I don’t consider myself a WN, but I am enthusiastically interested in all things dissident right. Evola has been something of a hero to me in my life lately, and it has been a pleasure and treasure as well to read articles by Collin Cleary. One day I’ll have to pick up one of Mr. Cleary’s books.

Dear Mister Cleary,

I thank you for the positive review of the book I translated from Italian into English, “Julius Evola Filosofo In Guerra 1943-1945” / “Julius Evola Philosopher And Magician In War 1943-1945”. The “…And Magician…” was not my translator’s semantic decision nor appreciated by the author of this work, Doctor Gianfranco de Turris. Although, we both understand why the Vermont publisher, Inner Traditions – Bear & Company, did so, and there aren’t any negative feelings from either of us. It is a very important undertaking by this publishing house, with regard to both Baron Julius Evola and the Perennial Philosophy, as well as other areas of study. I’m grateful for your kindness in pointing out that I meant Third Estate and not Third State, on page 159 of Chapter Nine, “The Hypothesis Of Rectified Masonic Rites”; instead of Masonic I have Freemasonic.

Notwithstanding, changes will made to the text of a translation by a publisher. I must say, whomever did the editing of my manuscript kept everything 98% to 99% as I had written. Unfortunately, the editorial board came to the decision that many of the added historical footnotes that I contributed for the reader of the English speaking world and those also added by Doctor de Turris himself, were considered to be too much for the readers of Inner Traditions – Bear & Company. A shame, but what can one do. The reason why our author supplied me with further footnotes is because this first edition in English is actually the fourth Italian edition translated. The Vermont publishing house had made a contract with its Lombard peer, Ugo Mursia Editore, for the rights to the third edition, and only subsequently did Doctor de Turris provide me with additions, corrections and revisions. So the fourth has seen the light of day in the translated English by me before the original Italian, which has yet to be published.

Let me state herein something that might seem immediately taken for granted but I’ve a reason for this, and as a POST SCRIPT you shall find a gift for you and the serious students of Metaphysics, given that I’m a Perennialsit myself. As you know, my translation is not literal; if it was it wouldn’t be a translation: it would be incomprehensible and a disservice to both English and Italian. I know both languages equally well, and I’m not blowing my own horn. My motive is because the two Metaphysical articles I put in a second Appendix, although 98% is what I translated, the 2% not mine make for a serious spiritual deviation at times, unintentionally I believe on the part of the editor, nevertheless, that I can not overlook. My English is modern like that of the editorial board, but not one that’s contemporary but neither archaic and erroneous. Proper adjectives and adverbs, clauses and sections of said clauses cannot be omitted. The richness of Baron Julius Evola’s Italian deserves a likewise English; and we must observe this is spiritual writing at its best, equal to that of his Perennialist peers: the Coomaraswamys, father Ananda Kentish and son, my friend Rama Ponnambulam, and Mister René Guénon, amongst others.

And so Mister Cleary I once again thank you and I hope , and if I may be so bold to say, I know that you and the readers as well as those who COMMENT will appreciate the two essays, by Baron Evola, that I PASTE herein from my manuscript of the translation. This is for all of you not for me, and if you desire the footnotes left out I’ll attempt to provide you with them. By the way, I have already started to work on this work’s sequel, “Elogio E Difesa Di Julius Evola: Il Barone E I Terroristi” /”The Baron And The Terrorists: Eulogy And Defence Of Julius Evola”, sanctioned by Doctor de Turris; a publisher is still required. God Bless, Eric Dennis Antonius Galati

POST SCRIPT:

APPENDIX II

LIBERATIONS

It is the maxim of ancient wisdom that events and all other aspects of life in themselves never count as much as the potentiality of having power over them and therefore the meaning that is attributed to them. The parallel axiom is Christianity itself that was able to speak of life as a trial and was able to make its own the motto: Vita Est Militia Super Terram.

In history’s calm and orderly periods this wisdom is accessible only to a select few because there are too many opportunities for complacency and desertion of oneself to consider the ephemeral important, hence forgetting the contingency and instability of what is by its very nature irremediable. This is the systematized foundation that in the broadest sense can be called the life and mentality of the burgess: it is an existence that no longer recognizes either abysses or heights to such a degree it cultivates interests in affections, desires, passions, as important as they may be from the merely terrestrial point of view, which become small and relative things from the spiritual and super-individual perspective which every human being worthy of the name should reflect upon.

Now, the disrupted and tragic periods of history can cause by the very forces they unleash, a greater number of people to be led to an awakening, toward a liberation. And basically, it is essentially from what is measured the most profound spirit of a race, its indomitability and its vitality in a superior sense. And even today in Italy on the home front, that no longer now perceives the difference between combatants and non-combatants confronted with so many tragic conjunctures, one must be more inclined to turn the eyes away from this and more often than not gaze upon that higher value in existence that unfortunately in the nature of things is commonly absent. From one day to another, more so from one hour to another, an individual can lose his home to a bombardment; what had been loved the most and to which one was most attached to, the very object of one’s most spontaneous feelings. Human existence becomes relative – it is a tragic and cruel sentiment, this – but it can also be the principle of a catharsis, the way to present what is the sole thing that can never be affected nor ever be destroyed. It must be recognized that for a complex set of reasons in the modern West there has tenaciously irradiated the superstition that the value of life is purely human, individual and worldly, a superstition that in other civilizations was and is almost unknown. In this regard, the fact the West professes nominally Christianity, results in it having had only a minimal influence upon this misbelief. The whole supernatural doctrine of the soul and survival in the afterlife did not substantially affect that superstition, it did not cause within the sensitivity of a sufficient number of human beings to understand the evidence of what did not start with birth and that can not end with death had virtually proceeded to act upon their daily life, biologically and emotionally. Instead, they convulsively hold on to a tree trunk which is nothing but the short stretch of an individual’s existence, doing everything to ignore the reality that such a grip does not have greater firmness than that of clinging to a clump of grass in order to save themselves from being carried away by a wild current.

At the present time because this has suddenly become blatantly clear, not as something “cerebral” or “devotional” but rather as a living fact accompanied with a feeling of liberation, all that today which is destructive and tragic can have, at least at best, a value to inspire. This is not about insensitivity and badly understood stoicism. Quite the contrary: it is a question of knowing and nurturing a sense of detachment from oneself, people and things, which should instill calm, unparalleled security and even the aforesaid indomitability. It is like a simplification, a stripping, in the disposition of anticipating, with a firm mind, everything, at the same time feeling something that goes beyond everything. And from this temperament will also be given the strength to always have the ability to start again, as from nothing, with a fresh and new mind, forgetting what has been or has been lost, having a look only for what is creative and positive: this can still be accomplished. A radical breakdown of the “bourgeois” that exists in every man is possible in these times more devastating than in any other. Yet in these very times man can rediscover himself, he can really stand before himself, to look at everything in harmony through the eyes of the beyond, so as to make once more essential and important what this should always be in a normal existence: the relationship between life and more than life, between the “human” and the “eternal”, between the “short-lived” and the “incorruptible”. And to discover the paths along which, to the exclusion of all ornamentation and pomposity, these values must be experienced positively and translate into pure strength for as many people as possible during these hours of trials and tribulations, is undoubtedly one of the main tasks of the political-spiritual “elite” of our nation.

{The above article, “Liberazioni” / “Liberations” by Julius Evola was published on the third of September, 1943 in the Turin daily newspaper “La Stampa” whose editor-in-chief at the time was Angelo Appiotti. The article that follows, “Uno Sguardo Nell’Oltretomba Con La Guida Di Un Lama Del Tibet” / A Gaze Into The Hereafter Under The Guidance Of A Tibetan Lama” also appeared in this Piedmont publication on the 19th of December, 1943 still under the direction of Appiotti. Both articles translated by Eric Dennis Antonius Galati}

A GAZE INTO THE HEREAFTER

UNDER THE GUIDANCE

OF A TIBETAN LAMA

The end of existence offers various alternatives, crossroads and possibilities, – visions and awakenings – spiritual disciplines that lead to “liberation” – to be born, to live and to die are but phases of a rhythm that comes from infinity and that goes towards the infinite.

One distinctive aspect in which there is a precise contrast between the views that came to predominate in the West and those that have been preserved – though not always in pure form – amongst almost all the peoples of the East, concerns the conception of death. According to Eastern teachings, the human state of existence is but a phase of a rhythm that comes from infinity and goes towards infinity. Death, in this way is anything but a tragedy: it is a simple change of state, one of the many that in this development has undergone an essentially super-personal principle. And since earthly birth is considered a death compared to previous non-human states, terrestrial death can also have the meaning of a birth in the superior sense of a transfiguring awakening. But in the teachings in question this last idea does not remain as it does for us, abstractly mystical. It acquires a positive meaning of a special tradition related to an “art of dying” and to a science of experiences that are to be expected in the afterlife.

Of this tradition its most characteristic expression is found in some Tibetan texts recently brought to the attention of the Western public through the translation of Lama Kazi Dawa Samdup and Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz. The most important of these texts is called “Bardo Thödol”, a term that can be roughly translated as follows: “Teaching to listen to alternatives”.

In fact, the central idea of this doctrine is that the fate of the afterlife is not univocal; the hereafter offers various alternatives, crossroads and possibilities, so that in this regard the attitude and behaviour of the soul of one, who was already a man, have a fundamental importance.

Asentimental Spirit

What is stRiki-Eiking in these teachings is their absolute asentimentality: their methodology is almost that of an operating room, ever so calm, lucid and precise. Neither “anguish” nor “mystery”, sic, is to be found there. In that regard, the translator isn’t mistaken when he speaks of it as a traveler’s guide to other worlds, a sort of “Baedeker Guide to other lands”. Who dies must keep the spirit calm and firm: with every ounce of strength, he must fight in order not to fall into a state of “sleep”: of coma, of swooning, which however, would be possible only if already in life one has devoted oneself to special spiritual disciplines, such as for example Yoga. The teachings that are then communicated to him, or of which he must commit to memory, have more or less this meaning: “KNOWING THAT YOU ARE GOING TO DIE. You will feel this, and this sensation in the body, these forces will impress upon you the feeling that you must escape, your breathing will stop, one sense after another shall cease – and then: from your very depths this state of consciousness will burst, this vertigo will take hold of you and apparitions shall form while you are brought forth out of the world of physical beings. Do not be dismayed, do not tremble. Instead, you must remember the meaning of what you will experience and how you should act.”

Of the Eastern traditions in general, the highest ideal is “liberation”. Liberation consists in achieving a state of unity with the supreme metaphysical reality. Although having the aspiration, he who to such a great extent hasn’t had the opportunity in the life of man to attain it, has the possibility of arriving directly to such a point in death, or within the states that immediately come after death, if he is capable of an act, that almost brings to mind the violence that is to be used to enter the Kingdom of Heaven, which is also mentioned in the Gospels. Everything would depend on an intrepid and lightning capacity of “identification”.

The Veil Will Be Lifted

At the same time, the premise is that man, in his profoundest nature, is identical not just to the various transcendent forces symbolized by the various divinities of the pantheon of those traditions, but also to the Supreme himself. The divine world would not have an objective reality distinct from the ego: the distinction would be a mere semblance, a product of “ignorance”. One believes oneself to be a man, while one is only a dormant god. But upon lifting the veil of ignorance from the body it is ravaged and torn, and the spirit would have – after a brief phase of stagnation corresponding to the undoing of the physiopsychic structure – the direct experience of these metaphysical powers and states, starting from the so-called “lightning – Light”: powers and states that are nothing but its own deepest essence.

There then is an alternative: either we are able, with an absolute impulse of the spirit, to “identify ourselves”, to feel like that “Light” – and at that exact moment “liberation” is reached, the “sleeping god” awakens. Or, if one is afraid, one goes backwards, and then one descends, one passes to other experiences, in which, like a shock given to a kaleidoscope, the same spiritual reality will present itself no longer in that absolute and naked form, but in the appearance of divine and personal beings. And here we repeat the same alternative, the same situation, the same trial.

Properly, there would be two degrees. In the first place, calm, luminous, powerful, divine forms would appear: then, destructive, terrible, threatening divine forms. In the one case as in the other case, according to the teaching in question, one should not permit oneself to be deceived nor frightened: it is the same mind that, almost like hallucinations, creates and projects all these figures in front of it: it is the same abysmal substance of the ego that was objected to, with the help of the images that were more familiar to the dead. Hence, it is acknowledged that the Hindu “will see” the Hindu deities, the Mohammedan the Islamic God, the Buddhist one of the divinized Buddhas, and so on, since they are different but equivalent forms of a purely mental phenomenon.

Everything rests on the “one who has left”, the deceased, to succeed in destroying the illusion of a difference between him and these images and to keep his blood cold, so to speak. This, however, is all the more difficult, as far as he is concerned, under the pressure of dark and irrational forces, to move away from the initial point of posthumous experiences. In fact it is more difficult to recognize oneself in a god who takes on the appearance of a person, and who was always adored as a distinct being, than in a form of pure light; and it is much less probable then that identification can occur in the face of “terrible” deities, unless in life, one hasn’t consecrated oneself to special cults. The veil of disillusion becomes increasingly dense, in a progressive lose of altitude, equivalent to a decrease of internal light. One falls and nears that destiny of passing once again into a conditioned and finite form of existence which, moreover, is not said to be once again terrestrial, as would those who assume it to be a dogma, in a gross and simplistic form: the theory of reincarnation.

The New Life

But whoever “remembers” until the end would have possibilities; in fact, the texts in question indicate spiritual actions, by means of which one is able to “open wide the matrix”, or at least if one succeeds in making a “choice” – one may choose the mode, the place and the plan of the new manifestation, of the new state of existence, among all those who in a last supreme moment of lucidity would confront the vision of the dead. The reappearance in the conditioned world would take place through a process that, in these Tibetan texts, presents a singular concordance with various views of psychoanalysis and which would imply an interruption of the continuity of consciousness: the memory of previous supersensitive experiences is erased, but what is maintained however, in the case of a “chosen birth”, is direction and impulse. In other words, we will have a being who although finding himself again to experience life as a “journey in the hours of the night”, is animated by a higher vocation and is overshadowed by a force from above, that is not one of the vulgar beings destined to “lose oneself like an arrow thrown into darkness” but a “noble”, who having a stronger impulse than himself will push towards the same end in which first trial he had failed, but that now with a new power will be once again confronted.

Therefore, these perspectives reveal these teachings, comforted by a thousand-year tradition. Whatever might be said concerning them, one point is certain: with them the horizons continue to be open and infinite in such a way that in the life of man, the contingencies, the obscurities, the tragedies, cannot result in being anything else but relativistic. In a nightmarish aspect it could be considered definitive, yet it might only be an episode with respect to something higher and stronger, which does not begin with birth and does not end with death, and that also has value as the principle of a superior calm and of an unparalleled, unshakable security in the face of every trial.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment