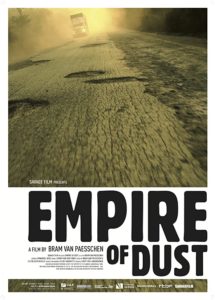

Empire of Dust

Posted By Beau Albrecht On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 2,131 words

2,131 words

The 2011 documentary Empire of Dust provides a one-of-a-kind portrayal of the difficulties facing a construction crew attempting to redo a badly dilapidated Congolese highway. Early on we meet Eddy, playing a key role as a translator. Clearly, he is exceptional: he knows Swahili, Chinese, French, and English, and this takes some doing. The other major figure is Lao Yang, the project manager for the CREC-7 construction company. Surely he’s one of the most flustered Oriental expatriates in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire).

Early on we see the job site, and thus far there’s not much to look at in the compound besides some sparse habitation trailers and construction equipment. In the morning, a small lineup of Chinese workers answers the roll call. Lao Yang announces that they’re going to have to get gravel. This, one could say, ends up being a problem.

It cuts to another scene, in which some new hires are lined up. (The Congolese look a little different from the blacks familiar to most of us; perhaps slightly Capoid.) They’re gaunt and expressionless, unlike the locals who’ve had steady work lately. Eddy tells them that they’re not going to get uniforms or flour until they’ve proven themselves. For now, they can’t lose their jackets or helmets or their pay will get docked. Later, Lao Yang asks him if he’s gone over the rules about not stealing; indeed, they’ve had the “larceny is bad” talk. It looks like neither are expecting too much from the new hires.

They get onto the highway, and the car bounces considerably from the ever-present potholes. (An earlier scene showed that the road was so badly damaged that sometimes an entire lane had eroded down to the dirt for short stretches.) It turns out that the highway was originally built in 1954. Lao Yang remarks: “Since the Belgians built it you guys did nothing to maintain it.” Eddy confirms, “Nothing.” They discuss history briefly. The Belgians ceded power because the Congolese wanted independence.

The quest for gravel

They arrive at the local gravel depot, but there’s no gravel. There is a mill to crush it from rocks, and they could indeed produce a truckload. The problem is that the boss isn’t there to tell them about their schedule. Lao Yang wonders what’s up with the wild goose chase. Why not call the boss, or have the acting supervisor there authorize it? (He does have a point; their job is to produce gravel, and it’s not like they had anything else to do.) Eddy explains to the Chinaman, “Their organization is rubbish. It’s not like back home.”

Then the boss does show up. Eddy chats with him privately in Swahili and tries to grease the skids. The Chinese company wants to buy the quarry directly, but they both agree that this would be bad. (Although the buyout would alleviate supply problems, one can’t blame Eddy for siding with local small business instead of the foreign company that employs him. Sad to say, too many Americans would sell out to a globalist corporation instead of siding with their own country.) The boss agrees to start producing a load. Then there’s a last-minute surprise with a dead battery on their equipment, necessitating a swap for a new one.

Back at the job site, it turns out that some of the fuel went missing; apparently, a regular occurrence. Later, Lao Yang remarks that “those thieves make me angry. I’d love to drag them and beat them up in front of the other blacks.” (The Congolese laborers seem half-starved, probably unable to afford cars, and they ride in on the back of a truck serving as a makeshift bus. I wonder if maybe they were sniffing the gasoline.) He chews out some of them for being lazy. Turnover is high, and indiscipline is a frequent problem. Later, they mock his attempts to speak their ranguage.

Then it turns out that a rearview mirror went missing from a truck, presumably stolen and fenced for $20. Afterward, they receive a delivery of pipes, and it turns out that they were shorted on the order by sixteen. That could’ve been prevented if the Kenyan delivery guy had counted them before returning. (Later, he smirks after being reminded to pay attention.) Meanwhile, the gravel supplier hasn’t been answering the phone. Lao Yang remarks, “It’s all so tiresome.” These words summarize the entire experience. For the cherry on top, Eddy’s sunglasses go missing from his vehicle.

The project manager also is in charge of procuring food. He heads to the local farm, complaining that he doesn’t like having to wait two hours every time. After getting there, he haggles for some chickens. One of the ones they sell him is sick; he wants it exchanged and they argue about it.

Then they try to buy rocks. The vendor is suspicious that they might be trying to make their own gravel. They explain that it’s for laying the pipe. They haggle over the price per cubic meter, but leave empty-handed. Later they try to procure some gravel. The mill is working on the order, so at least there’s some progress at last.

At night, the locals amongst themselves joke about their relations with the Chinese. Apparently, Africa is no exception to the fact that managing diversity at work is a big headache. At least they’re laughing about it and taking it far less hard than it would be in the USA:

“I think it’s true. I don’t know if someone told them they were going to find apes here.”

“Stop talking about the ape thing.”

“It sets a bad example.”

Eddy replies, “Don’t you think they see you as an ape?”

“They said to Mutombo, ‘black man same as ape.'”

“They look like pigs.”

In the morning, they’re getting a bit desperate for the gravel. However, Lao Yang sees that the dump truck’s tailgate doesn’t close properly, and fears that even if they brace it, still they’re at risk of losing the load on the way back. It had been damaged in the country, rendered nearly useless after two years, unlike trucks in China that are still in great shape after four years. His observations are similar in nature to the aggravation over tools broken frequently in antebellum Dixie.

When a black guy drives the truck, he does a lot of damage. In China, the trucks are well maintained. . . Black drivers think they can fly when they accelerate. The wheels spin like crazy. The tires wear out fast so their trucks don’t drive well.

Soon, he laments to Eddy about a rail line in disuse, built during the colonial era: “The infrastructure has gone to waste. It hurts to see it.”

They finally pick up the long-anticipated load of gravel. They have to weld the tailgate to secure it. They do so, but with some complications. Then they try to measure the cargo bed’s dimensions, but the cheap tape measure won’t hold up. Eddy gets in a good line; about time he had a chance to return fire: “Of course, it’s made in China.”

On the way back, Lao Yang narrates about their role. He builds the road, and in exchange, the Congolese government will allow the company to operate a mine. (This has become a rather common arrangement in Africa. After European colonialism ended, development screeched to a halt until the Chinese resumed with their “colonialism lite.”) However, after two years into the deal and $2.1 billion invested, the mine still isn’t in operation. He laments:

People here don’t have any sense of time. It’s hard to adapt to life here. They waste time in almost everything they do. So we go back and forth. People here are used to extreme circumstances. Look at their tough environment. They adapted to it. Only the strongest survive in this environment. That’s why they are all so well built. What’s more, they all adore football.

Upon arrival, Lao Yang finds that the level is lower than he thought. (They did check it earlier, so the problem is likely from settlement after the truck bounced over all those potholes.) They bash the tailgate open, and finally they have their load of gravel.

Wrapping up

An announcer of the local radio station, who during the movie served the function of the chorus in a Greek play, states that CREC-3 is preparing to work on the cobalt mines. This guy is a trip:

Will these companies stay for long? That’s what I wonder. . . But if it’s not the Chinese it will be someone else. Why not the Belgians again or talking penguins or even Martians?

The next day, it shows a public commemoration for the project. (Presumably, the chubby lady in the bright dashiki is the mayor who the radio announcer gossiped about before; a chair had collapsed under her during a meeting.) A white emcee gives a pep talk, a band plays, a priest prepares to say a benediction, and a road grader pushes dirt.

Back at the compound, Lao Yang laments about government inefficiency and the fruitless negotiations to buy out the quarry. He says to Eddy, who listens impassively:

You were governed by a European country for so long. You should’ve learned how things worked. It wasn’t that long ago. . . You went backwards instead of forwards. Look at your railways. High technology from the 1930s. We didn’t even have it in China back then. Look at the railroads in the mines. The cable lines are fucked up. I can’t bear to see that. You neglected the things others had left you. What’s more, you completely destroyed them.

The last lines of the film, spoken with the backdrop of a pretty sunset over the dusty savannah, are politically incorrect remarks about spendthrift Congolese blowing their paychecks on booze. This includes: “They stand at the bar drinking a beer. And then start shaking their behinds. It’s wonderful.”

Impressions

One surprise is that it’s okay for an Oriental in Africa to talk candidly about Africans, even directly to them. Meanwhile, white Americans in our own country wouldn’t be caught dead discussing colored employees on camera. Anyone doing so would get hauled into the HR Department for an experience somewhat reminiscent of a Maoist struggle session [2]. The epic flapdoodle [3] over a secretly taped 1994 conversation between Texaco executives is an example of what can happen. (That’s the one in which an analogy was made about black jelly beans sticking to the bottom of the bag, or words to that effect.) Long ago, who would’ve guessed that the ChiComs would lighten up, but we’d start following their earlier example?

The road construction project was pretty much a Chinese fire drill, but in this case, it wasn’t their fault. Eddy said that the country isn’t developed because their government wasn’t prepared for independence. (Does he know better, and is trying to hang onto national pride?) It would be hard for historical factors to explain all the incompetence, petty larceny, indiscipline, and failure to attend to maintenance, but let’s examine the argument on its own terms.

The Congolese transition to home rule was fairly orderly, even if not entirely peaceful. They merely had to assume control over colonial government institutions already in place. Over fifty years, what happened? Patrice Lumumba got whacked, the long regime of the infamous Mobutu Sese-Seko came and went, the special snowflake Laurent Kabila took over, then he got whacked and his son Joseph succeeded him. (The movie unfolds during that administration.) By contrast, in 1776, the United States was only an idea. The Founders had to fight for independence, with no orderly handover. They created everything from the ground up: a provisional confederation, then a radically new Constitution, and a permanent national government infrastructure. Fifty years later, John Quincy Adams was at the helm. He was doing a better job of it than Joseph Kabila.

Therefore, I’ll have to disagree with Eddy’s conclusion. I’d say that maybe there’s a little more to the problem than history. The Lynn and Vanhanen study of intelligence by country [4] lists the Democratic Republic of the Congo as having an average 78 IQ. (That might not be much to write home about, but it’s certainly not the lowest. That honor belongs to Equatorial Guinea, averaging a literally retarded 59 IQ.) Maybe the disorder that the movie shows is just the best that the Congolese can do.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [5] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.