Chief Pontiac’s Revenge: The Story of Detroit’s Deindustrialization

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 2,804 words

2,804 words

There is no city quite like Detroit, Michigan that exemplifies American deindustrialization. If one flies into the city’s airport at night, one looks down on a dark void, occasionally lit by streetlamps shining their light upon a ruin. By day, things look no better. Vast stretches of the city have become urban prairie [1]. The story of Detroit is emblematic of the story of American industrial greatness and industrial decline. It is a Greek Tragedy played out in the Midwest. It is where America’s virtues brought so many to the top of an Olympus upon a Pegasus of rolling iron and the internal combustion engine, but old fashioned folly and the American Original Sin of importing African slaves brought a great fall.

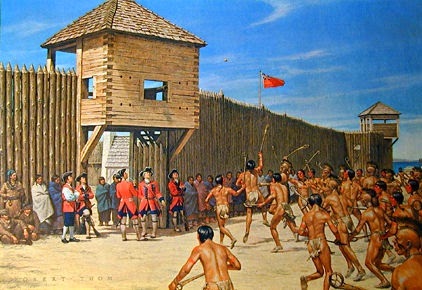

Detroit was founded by French in 1701 as a fortified trading post. After the French and Indian War, Fort Detroit passed into the hands of the British. Racial problems of white vs. non-white followed shortly thereafter. During Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763, the Indians besieged the fort and ate a captured British soldier.

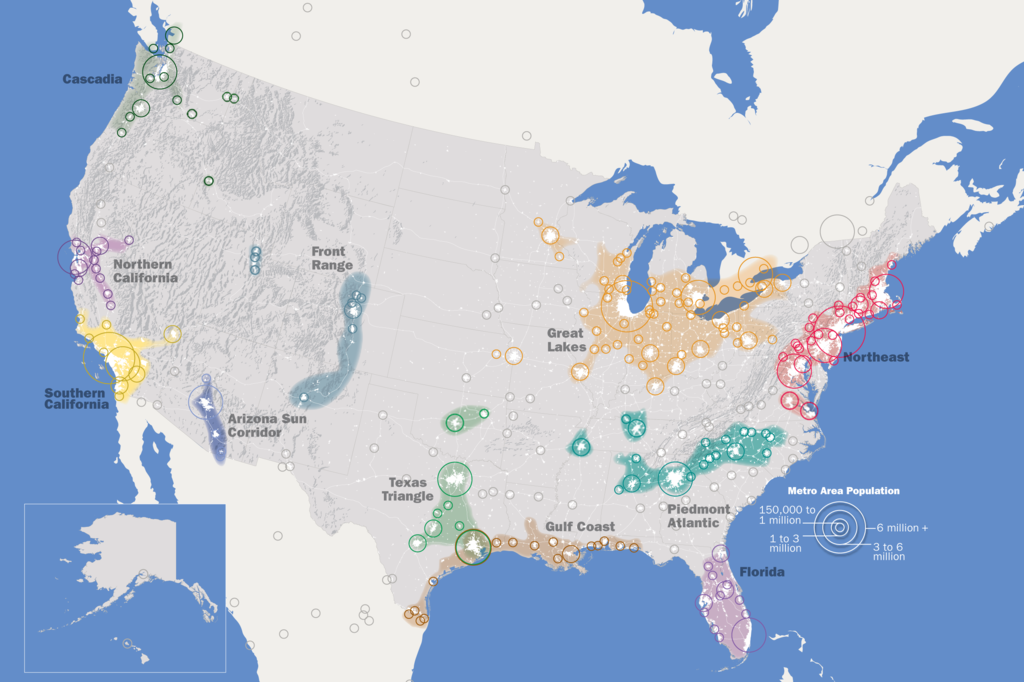

Shipping routes of the Great Lakes. [2] Detroit is positioned at a chokepoint and is thus a key port. The city was a battlefield due to this reason during Pontiac’s Rebellion and the War of 1812.

Detroit became part of the United States following the Revolutionary War, but was briefly lost to the British during the War of 1812. The end of that conflict opened up the Midwest to American settlement in earnest. Madison Grant writes,

As late as the beginning of the War of 1812 four-fifths of the 5000 people in Michigan were French. In 1817 the first steamboat appeared on the waters of Lake Erie and the Erie Canal was begun, and from that time the Americanization of the territory was rapid. . . By 1830 a hundred ships, both steam and sail, were on the Lakes, and a daily line ran between Buffalo and Detroit. In 1836 when the State Constitution was adopted the population was nearly 100,000, mainly from New England and its extension in western New York. The Empire State can be very definitely be called a parent of Michigan. [1] [3]

Michigan’s state flag (left) is remarkably like New York’s (right).

The cultural ties to New York, especially Buffalo and the rest of Upstate, can be seen when looking at the two states’ respective flags side by side. There are also similarities — though not as many — to Pennsylvania’s banner [4]. Essentially, Detroit is located at the vortex of commerce on the Great Lakes and the industrious people originating in New England [5] and Pennsylvania [6].

Michigan became the location of vast industries because of its Yankee and German/Anglo-Pennsylvanian settlers (left). It also benefited from the fact that nearby Ontario was also heavily populated by loyalist Pennsylvanians with a similar outlook and work ethic.

A look into the backgrounds of the leaders of the Industrial Revolution in Michigan in particular and the auto industry more generally shows that nearly all were part of the New England, Quaker, and Pennsylvania Dutch semi-admixed culture of the Midwest. Consider:

Will Keith Kellogg, (Yankee): Created the food company in Battle Creek, Michigan. In line with the traditions of his Puritan forbearers, he was motivated to manufacture and sell breakfast cereal due to his Seventh Day Adventist beliefs. That denomination’s creation was inspired by a Yankee named Captain William Miller of Upstate New York.

John Harvey Kellogg, (Yankee): Brother to Will (above). He invented corn flakes and focused on healthy living and morality. He also supported the eugenics movement which was a proxy conflict in the struggle of Yankees vs. Jews. (There’s always a eugenics policy!) That conflict is in play among the captains of Michigan’s industry as with anyplace else, from John Wayne’s Jew-aware associates [7], to the Kent State shootings [8]. The Dearborn Independent published The International Jew [9], which exposed the workings of the organized Jewish community. The Ford Company executive William J. Cameron helped propagate the Christian Identity movement [10].

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [11]

Alfred P. Sloan, (Yankee): President and CEO of General Motors. His ancestry also included Anglo New Yorkers. The migration of British settlers directly to New York after the Second Anglo-Dutch War is an unappreciated folk migration and influence on America. Sloan was probably also wise to the JQ. He was not enthusiastic about American involvement in the War in Europe.

Thomas A. Edison [12] (Yankee): Grew up in Port Huron, Michigan. He led a revolution in the use of electricity. He got his start working in a telegraph office, itself a technology developed by another Yankee, Samuel Morse.

The Studebaker Brothers, (Pennsylvania Dutch [2 [13]]): Founded the Studebaker car company in South Bend, Indiana, which is very close to Michigan. The Studebaker Company no longer makes cars, but its corporate DNA still exists in various industrial enterprises.

Harvey S. Firestone, (Pennsylvania Dutch): Founded the tire company.

William R. Gorham, (Yankee): Gorham was a frustrated American engineer who moved to Japan, became a Japanese citizen before World War II, and then afterward helped put Japan on the path toward quality-focused industrialization.

Frederick Winslow Taylor [14], (Yankee and Anglo-Pennsylvania Quaker): He was an expert in developing efficient industrial processes including how to improve relations between labor and management. If you’ve done any sort of business process development, you are following in Taylor’s footsteps. [3] [15]

Henry Ford and His Model T

Frederick Winslow Taylor was a major influence on Henry Ford [16], the industrialist that made the first practical automobile. Henry Ford was descended from Irish immigrant pioneers to Michigan, but they were not Scots-Irish from Northern Ireland or entirely of native Irish stock. The Ford family was Anglo-Irish. They were descended from post-Tudor Conquest English pioneers that originated in the West Country of England, which was a secondary origin point of the Puritans who moved to New England.

When Henry Ford moved to Detroit in 1879, the city was already filled with workshops and garages improving on the steam engine and improving and combining emerging technologies. It was not until he was in his forties that Ford’s experience, professional connections, and considerable mechanical talents came together. In 1903 he founded Ford (the Company) and in 1908 he produced his first Model T.

The Model T is an example of a product perfectly suited to its place and time. The car was designed to fit the existing road infrastructure. The roads then were unpaved and built for horse and wagon transport. The Model T was also easy to fix. Ford’s automobile produced generations of American men that knew how to get an engine going through tinkering. His company also supported other industries. Road builders, oilmen, tool and die makers, gas station owners, etc. all prospered with Ford.

Henry Ford was pretty unguarded and reporters hung out around his office all the time, so his career and peccadillos are well documented. Additionally, how his industry developed, from new to routine so to speak, has parallels to other industries.

Henry Ford focused on making one type of car as quickly and cheaply as possible. Key to this was the assembly line. It broke down how to do a process in simple steps that anyone could learn quickly. He solved his labor problems by paying his employees well. He continued to improve production methods for the Model T, but not the Model T itself.

Like most industry leaders in new fields that came after the auto industry have discovered, being first has some disadvantages. General Motors (GM) imitated all that Ford did in the factories, but worked to improve the cars and update them every year. GM also created a car for every type of consumer. Chevrolet was the downmarket car and the Cadillac became the luxury brand. A customer would start with a Chevy and then work their way up within the General Motors family. Due to General Motors’ innovations, Ford had to create the Model A and continue to update their cars.

Henry Ford’s increasingly tyrannical behavior and cruelty to his son Edsel is legendary. Edsel very likely died before his time because of his father’s abuse. Suffice to say, Henry Ford’s leadership style and narrow-minded insistence on only producing one type of car in the face of GM’s increasing competitiveness nearly destroyed the company.

During World War II, Henry Ford II (the grandson) was released from service in the US Navy to head the company to produce for the war effort. Suffice to say, companies like Ford helped win that terrible conflict.

American industry’s post-war structural flaws

In the post-war years, Ford and the other automakers in Detroit were prosperous. There was also conformity and conservatism in dress and tastes among the auto executives. Apparently, “all of them” like to drink Blue Nun wine. None of them anticipated the oil crisis, and they’d innovated little between 1950 and 1979.

All industries that produce something must operate on three supporting legs. The first leg is accounting, the second is marketing, and the final leg is engineering. As mentioned above, Henry Ford worked hard on engineering — in the factory — but not so much on the Model T. GM focused on engineering better cars and then marketed them well.

By the 1950s, all the Detroit auto men were concerned with accounting. The companies all had so much cash that there was a temptation to make money through lending rather than production. Henry Ford II’s decisions were warped due to this situation. From his viewpoint, cars that needed extensive engineering and then didn’t sell well took money from his family.

Then there was the United Auto Workers union. It was led by Walter Reuther, a hardworking, pious Lutheran labor leader whose parents came from Germany. It was Reuther who advised President Kennedy on a way to suppress Right-wing radio [17] in the early 1960s.

Although he probably saw himself as a radical, he was really a mainstream left-of-center technocrat of the sort that thrived in the middle twentieth century. His trick was to threaten a strike just as one of the auto companies was going to manufacture a profitable line of cars. The executives would yield, the workers got more pay, and benefits and the costs were passed on to the consumer. In the 1960s the ground moved under Reuther’s feet. He ended up supporting LBJ’s Vietnam effort as a ploy to gain more money for his workers which alienated him from other Leftists, and the Scandinavian-style socialism he endorsed failed to work with Africans after the “civil rights” situation.

The Rust Belt is the single greatest untapped resource in the United States.

Pontiac’s Revenge

Cotton Mather said to Benjamin Franklin [18]: “You. . . have the world before you stoop as you go through it, and you will miss many hard thumps.” By the early 1960s, Detroit’s auto companies felt that they had the world before them. They didn’t see the Japanese auto industry, the Middle Eastern oil crisis, and Negro Rioting were about to deliver a series of hard thumps.

These hard thumps should be called Pontiac’s Revenge, after the Indian Chieftain who fought the English at the end of the French and Indian War. Pontiac’s Rebellion took place in the region that became today’s rusting American Industrial heartland.

Fort Michilimackinac was successfully taken by Indians after they used a lacrosse game as a ruse.

Probably due to the influence of the New Dealers throughout the US government during World War II, the American occupation officials made Japan a left-of-center society like the US was at the time. Eventually, there were Communist labor unions causing all sorts of problems in Japan. The Japanese handled the situation well. In one case, they jailed a powerful but troublesome union leader, Tetsuo Masuda, for just enough time to create a new, more cooperative union and cut away Masuda’s power. Meanwhile, the Japanese engineers and craftsmen had a great appreciation for American technical know-how in the mid-twentieth century.

The Japanese engineers put their educational credentials on the shelf and listened to ordinary shop workers about tricks to make brakes slow a car in a smoother way. They asked many questions of the American engineers and improved their factories.

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [19]

Meanwhile, Ford got the “Whiz Kids.” They were mostly math experts who worked in the Pentagon during World War II. They were led by Robert McNamara. Under McNamara’s leadership, Ford’s corporate culture became one of numbers and reports. The company invested heavily in designing boring cars. Additionally, McNamara didn’t care what the shop managers and workmen were doing. He was interested in accounts. Eventually a culture of lying developed at Ford that matched the culture of lying during the Vietnam War when McNamara was US Secretary of Defense.

Robert McNamara misread data. He never really learned how to make quality cars at Ford and allowed the factories to continue to drift into obsolescence. I believe that the McNamara type of leader — extremely smart, ambitious, but lacking the ability to grasp great truths — is the result of the “civil rights” movement. If one believes all the nonsense about African equality, dreams, red clay soil, and mountaintops, then the type of person that rises to the top can’t really look hard at anything. Those that embrace and believe in “civil rights” ultimately stop thinking.

The next great disaster in Detroit and the entire Rust Belt region was caused by the migration of blacks from the South to the North. This migration is every bit as much Jefferson Davis’s revenge as Pontiac’s. DNA studies [20] have shown that the first Negroes to head to the North had a great deal of white ancestry. They were probably the children of the slave owners and one of their slave concubines that were encouraged to head out. Nonetheless, very few blacks lived in the North for most of American history. During the First World War, blacks were enticed to move to Detroit. They were spurred on by the mechanization of farming, which made sharecropping unnecessary.

To make a long story short, Africans destroyed Detroit in the same way they destroyed Haiti and everything else. By 1968, whites had fled the suburbs. By the late 1960s, all the great cities of the North had burned in the now not-unusual sub-Saharan style. The continued presence of Congoids makes recovery of these areas more difficult.

He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor. . .

Looking at the people of the American Midwest is important for a number of reasons. First, whatever side of an issue the Anglo-Pennsylvanian Quakers settle on usually sets to the tone for the rest of the United States. Second, having Northern Yankees on one’s side is a big advantage. Next is that the area is underutilized. It still has outstanding universities, a great transportation network, and a hardworking, mostly white population that is waiting for opportunity. Finally, understanding the hard truth about how to make a living is important.

Counter-Currents’ Spencer Quinn talks about weaponizing money [21]. It’s a great concept, but to get money, one needs to make a living. Indeed, there is one sure way to make money. One needs to find something to do that can be monetized and then work very hard at it. With today’s easy way to invest using smartphone applications, one can put spare money in an interest-bearing investment, and well, time is money.

All those captains of industry found something that they could do and made money for themselves and those around them. Henry Ford’s initial investors became millionaires. Those that owned the garages and workshops of Detroit in the 1880s became wealthy when they sold out or consolidated. The houses they owned became more valuable. In one’s career, one should work as hard as Henry Ford.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [22] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [23] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Suggested further reading

David Halberstam, The Reckoning. New York: Open Road Integrated Media, 2012 (1986).

Paul Kersey, Escape from Detroit: The Collapse of America’s Black Metropolis. CreateSpace Publishing, 2012

Ze’ev Chafets, Devil’s Night and Other True Tales of Detroit. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

Notes

[1] [24] Madison Grant, The Conquest of a Continent. York, South Carolina: Liberty Bell Publications, 2004, p. 177.

[2] [25] I wish to admit I could be casting too broad a definition of Pennsylvania Dutch in this article, in that Pennsylvania Dutch could be interpreted to only refer to those in Pennsylvania who are in some particular Protestant sect. In this case, I am calling anyone Pennsylvania Dutch if their ancestry is German and can be traced to Pennsylvania in the 1700s.

[3] [26] See also: Taylor, Frederick Winslow, Shop Management. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1903.