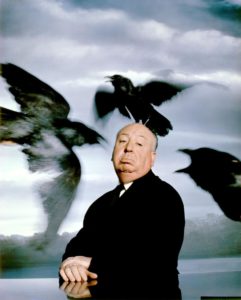

The Birds Or: Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Coronavirus (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock & Heidegger), Part Nine

Posted By Derek Hawthorne On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled5,423 words

Part 1 [1], Part 2 [2], Part 3 [3], Part 4 [4], Part 5 [5], Part 6 [6], Part 7 [7], Part 8 [8]

Mitch gathers Melanie’s still unconscious body into his arms and carries her down the stairs. Lydia walks ahead of him, carrying an oil lamp. “Oh, poor thing! Poor thing!” she says. Her resentment toward Melanie now completely gone, she feels only pity. Lydia goes to fetch bandages, as Mitch lays Melanie on the living room sofa. He asks Cathy to get some brandy, and the little girl brings over a bottle and a glass. Mitch now examines Melanie’s wounds in the light and grimaces. The gash on her forehead appears deep and there are cuts on both her cheeks.

Suddenly, Melanie opens her eyes wide and begins frantically clawing the air. She does not see Mitch, or that her surroundings have changed. She is still fighting the birds. Mitch grabs her arms, which are also covered in cuts and scratches. “No, no. It’s all right. It’s all right,” he says, soothingly, and presses her arms into her chest. Cathy is overcome with emotion and turns away, crying quietly. Mitch tries to get Melanie to sip some brandy, but her lips do not move and she looks away from him, not looking at anything in particular, seeing nothing. She just lies there, catatonic, arms crossed over her chest like a corpse.

Lydia enters with water, antiseptic, and bandages. She and Mitch then begin cleaning and dressing Melanie’s wounds. At this point, the screenplay contains some small but significant differences from the completed film. First of all, Mitch begins unrolling bandages, but his hands are trembling and he drops the roll. “Let me do that, Mitch,” Lydia says gently. “I can handle it,” he insists. He doesn’t want to be treated like a little boy. With emphasis, Lydia responds, “I know you can.” Hunter specifies that “her eyes meet his,” and she says, “But I’d like to.” Here, two things are happening. She is affirming that he is a man, but also signaling her desire to care for Melanie.

Furthermore, in the screenplay, Melanie speaks, though she is somewhat delirious. “Please don’t mess me up with bandages, Mrs. Brenner,” she says, and Lydia shushes her. Melanie continues to talk for the rest of the screenplay and is not depicted as catatonic. In the film, she remains in a stupor, aside from uttering two words, as we shall see. Hitchcock’s changes to Hunter’s script emphasize Melanie’s complete helplessness and reduction to an infantile state.

In the film, and in the screenplay, Mitch insists that they must get Melanie to a hospital. His plan is to head for San Francisco. Lydia says she doubts that they will make it, but Mitch insists that they have to try. “I’m frightened, terribly frightened,” Lydia says. “I don’t know what’s outside there.” In the screenplay, Mitch responds, “What do we have to know, Mother? We’re all together, we all love each other, we all need each other. What else is there? Mother, I want us to stay alive!”

It’s a melodramatic line and was rightfully cut, but Lydia’s response (again, only in the screenplay) is interesting. She nods and says, “I started to say. . . inside. . .” What does this mean? She had said a moment earlier “I don’t know what’s outside there.” The line is slightly different in the script, and Lydia hesitates at the beginning of it: “I . . . I don’t know what’s out there.” Does she mean that she had started to say “I don’t know what’s inside there”? Inside where? In the screenplay, Mitch holds out his hand to her and says, “You don’t have to.” Was Lydia about to commit a Freudian slip? Was she about to confess that she is afraid of what’s happening in the house, between Mitch and Melanie? Or does she not know what is inside herself, inside her heart, perhaps? This is true, but in the end, she finds out.

In all the parts of this series, I have included discussion of the differences between the screenplay and the film because those differences shed light on the film’s meaning. Hitchcock’s changes to the screenplay often give us important clues to the director’s intentions and what he thought the point of the film was. In almost every case, Hitchcock’s changes improve the story and give it depth (I discuss this point fairly extensively in part six [6]). Hunter’s dialogue is sometimes flabby and melodramatic, and Hitchcock pruned it quite intelligently. However, there is material that was cut from the script that sometimes sheds more light on the characters and their motivations, and sometimes one wishes that it had been left in. As I have demonstrated here, this is particularly true with some of the dialogue between Mitch and Lydia. The troubled nature of this mother-son relationship is clearer in the screenplay than it is in the finished film.

In any case, Mitch decides that they will take Melanie’s Aston Martin, because it will be faster than their pickup truck. This is a somewhat strange decision, since Melanie’s car is a convertible with a canopy that could easily be torn to pieces by the birds — but we’ll find out the real reason for this in a moment, and it has to do with Hunter’s original, planned ending to the film. It only took about two dozen viewings of this film over the years for me to remember that Mitch was seen with a car earlier. It was a 1962 Ford Galaxie 500 Town Victoria 75A — a four-door sedan with a hardtop. Why not use that car? It would be faster than the truck and more secure than the Aston Martin. Did Mitch leave it at the Tides when he went to meet Melanie? We’ll never know.

Mitch’s car, a 1962 Ford Galaxie 500 Town Victoria 75A. But whatever became of it?

Mitch heads to the front door, intending to get Melanie’s car out of the garage and bring it around. Lydia says, “Mitch, see if you can get anything on the car radio.” Hitchcock then shows us the exterior of the Brenner’s front door, in closeup. It is covered in scratches and gouges. The door opens and Mitch moves into view. As he looks at the front yard, his face takes on an expression of horror. Then we see his point of view: birds cover the entire earth, or at least it looks that way. Birds cover the ground and are perched on every object within sight. Part of the image is another matte painting by Albert Whitlock. It shows sunlight streaming through the clouds in the distance, which some have interpreted as a sign of hope [9].

Some of the birds in the shot are real, and we can see them moving. Some are fake (it is safe to assume in this film that anytime a bird is not moving it is stuffed prop or a cardboard cutout). The real birds were, in some cases, tied to the objects they perch on, via cords placed around their talons. Some were drugged. And some were actually chickens and ducks (sometimes with dyed plumage), though these were placed in the background. Paul Ridge, a representative of the American Humane Association, was always on set to make sure that the birds were well treated. He reported no problems. Bird trainer Ray Berwick seems to have been very fond of his charges, and kept some as pets.

Mitch swallows hard and slowly moves out onto the porch. Gulls surround his feet. Indeed, he must inch forward as gently as possible, as the ground is covered in hundreds of birds. Needless to say, he is desperate not to excite them. As he begins to descend the steps, he reaches out to touch the wooden railing. Several ravens are perched there and one of them caws loudly and gives his hand a nasty peck. This particular raven was the aptly-named Nosey, Berwick’s pet. In order to produce this reaction from Nosey, Rod Taylor’s hand was smeared with meat. (Some descriptions of this scene identify Nosey as a crow, but he looks like a raven to me. Berwick said years later: “Pound for pound, I think the raven and cockatoo are the most intelligent beings on earth.”)

Despite the presence of countless numbers of winged mankillers, an eerie calm prevails. This is heightened by the sound effects, which play quietly in the background. We hear wings fluttering softly, and little cooing and cawing noises. Behind these, however, there is what sounds like the rush of wind, though it is creepy and artificial. A similar sound effect accompanies the “God’s eye view” shot of Bodega Bay, as the gulls mass for their attack, discussed extensively in part six [6].

Mitch succeeds in making it to the side door of the garage, even as gulls nip at his pant legs. He enters the structure, which is not attached to the house, and is about to try and open the garage door when he remembers Lydia’s request that he listen to the car radio. He gets into Melanie’s car and turns the radio on, then locates a station with news on Bodega Bay. The announcer is in the middle of reading the story:

. . . The bird attacks have subsided for the time being. Bodega Bay seems to be the center, though there are reports of minor attacks on Sebastopol and a few on Santa Rosa. Bodega Bay has been cordoned off by roadblocks. Most of the townspeople have managed to get out, but there are still some isolated pockets of people. No decision has been arrived at yet as to what the next step will be but there’s been some discussion as to whether the military should go in. It appears that the bird attacks come in waves with long intervals between. The reason for this does not seem clear as yet.

Nor will it ever be clear.

Mitch switches off the radio, gets out, and then very carefully opens the garage door. He returns to the car, starts it, and then allows the vehicle to roll ever so slowly out of the garage and up to the front door. The car moves through a veritable sea of gulls, and Mitch is trying desperately hard not to crush any of them. He carefully gets out of the car and then slowly moves up the front steps, wading through more gulls. Finally, he manages to slip back into the house, quickly shutting the door behind him. For those seeing the film for the first time (and even multiple times), the suspense in this scene is agonizing.

Inside the house, Lydia sits on the couch, holding Melanie close. She has on a brown overcoat and has helped Melanie into her mink. The authors of Cinemafantastique’s 1980 article on the making of the film [9] comment, correctly, that the mink is “now a hollow reminder of her status, a privileged position which has failed to protect her from the wrath of the birds.” Melanie’s head is now bandaged, with a thin diagonal line of blood seeping through the gauze. The cuts on her cheeks also seem to still be bleeding. Her hands and wrists are also bandaged. She stares straight ahead, her expression completely vacant. Cathy stands over her, putting on her own little coat, studying Melanie with a mixture of fear and incomprehension.

Mitch and Lydia now help Melanie up and, supporting her, they move toward the front door. The camera holds a medium shot of Mitch, Melanie, and Lydia, tracking backward and into the darkest part of the room. The trio are enveloped in shadow. Then we see Mitch reach his hand downward and out of frame. We hear the doorknob turning. Mitch’s arm sweeps back toward his body, opening the door and illuminating the three characters with the morning light. I have described these actions in detail, because this is actually one of the most remarkable shots in the film. Most viewers will not realize, even on repeat viewings, that there is actually no door. And there could not be – otherwise, the camera could not have photographed the trio. The entire effect was accomplished with lighting, plus Rod Taylor pantomiming opening the door. The shot has been referred to as Hitchcock’s “magic door trick.” [10] He employed a similar technique in 1950’s Stage Fright [11].

We now see their point of view: the convertible sitting in front of the house, surrounded by birds. If anything, there now seem to be more birds in the yard than there were before. As Mitch and Lydia lead Melanie out, the latter suddenly wakes up from her stupor. She looks around at the birds, eyes wild, and then cries “No. No!” They are the last lines she will utter in the film. Mitch and Lydia manage to calm her, and as the three move down the steps and toward the car, Hitchcock intercuts shots of Lydia and Melanie, both of them terrified. The ravens are seen again on the railing, this time cawing sharply. Are the birds about to attack?

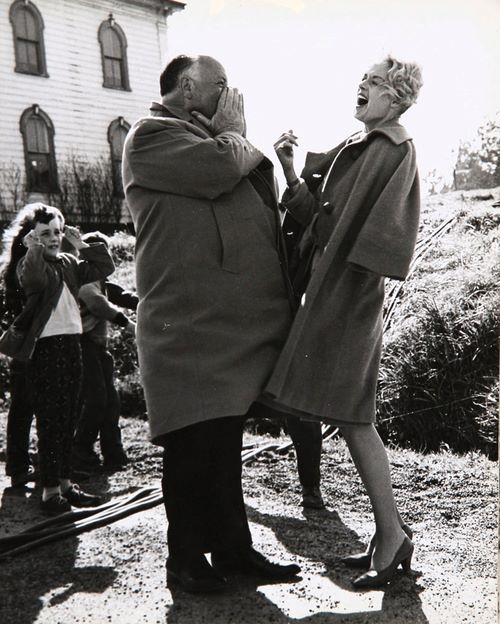

Publicity shot — Hitch poses while the crew prepares the house for the final scene.

Finally, they reach the car. Mitch opens the passenger side door and helps his mother and Melanie into the back seat. Cathy now calls to him from the front porch, the caged lovebirds at her feet. [1] [12] “Can I bring the lovebirds, Mitch?” she says hesitantly. “They haven’t harmed anyone.” “All right, bring them,” he responds. This always elicits from me a groan or at least a smirk. Commentators have interpreted this small touch as a sign of “hope” at the film’s end. Actually, its inclusion is deeply pessimistic. Hitchcock is promising us that the human foolishness will continue. Cathy is like the little child in Isaiah (see part seven [7]): “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the young goat, the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” No, actually, it won’t be that way. But we never learn. So very foolish, so very white.

Hitchcock directs the final scene.

Cathy picks up the birdcage and Mitch helps her into the front passenger seat. In the back, we see that Melanie is huddled against Lydia. The older woman looks down when she realizes that Melanie is grasping her wrist tightly. Melanie looks up at her, with an expression that conveys, all at once, pain, fear, and something else. Is it love? The Melanie we met at the beginning of the film seems to be gone. She now seems as innocent as a child — and that is, indeed, what she has been reduced to. Lydia looks back at her, for the first time, with real affection. With love, even. She presses her head against Melanie’s. It is a touching moment, beautifully photographed.

In this moment, which lasts just twelve seconds, several things have happened that are of great significance for our characters. The first and most obvious is that Lydia has accepted Melanie. In doing so, further, she releases Mitch; she relinquishes her control over him. This is tantamount to overcoming her fear of abandonment – by means of abandoning herself, and her selfish desire to hold onto her son. She now accepts Mitch not as a substitute husband, but as a son and as a man, who can and will and must leave her.

But Melanie too is changed in this moment. She overcomes her own abandonment through a surrogate mother figure. She is born again. No longer frivolous, spiteful, and duplicitous, she has been changed by her commitment to this family — a largely unchosen commitment, that has blossomed into love. The birds have freed her to become who she really is. She could not do this on her own.

As to Mitch, he has achieved, by this point, a kind of masculine apotheosis. In primal conflict with nature, he has risen to the occasion as a man and protected the women. His mother has finally released him, and he has another to care for — someone with whom, we sense, he will begin a new life. Not “when all of this is over,” but now. For “all of this” is never over. Life continues amidst adversity. It always has and always will.

As to Cathy, her own story and character are not of great importance here, but we can see that she has been strengthened through the addition of Melanie to the family.

Mitch starts the car. Immediately, the birds begin cawing and squawking angrily. The car moves forward. Then we see the same shot of the yard shown a few minutes ago, the one partially accomplished with a matte painting. Slowly, the car moves through the yard, off the property, and onto the road, as the sound of the birds becomes louder and more ominous. As the car advances down the road, it picks up speed. It continues to move far away from us, then we see it round a bend. Just as the car almost completely disappears from view, the picture fades quickly to black. There is a pause, and then a simple title card ends the film: “A Universal Release.” The words are superimposed over a stylized globe, in the same color scheme established in the opening credits. The final shot of the film lasts twenty-seven seconds. It is a composite shot, involving not only Whitlock’s matte painting but also thirty-two different exposures. Hitchcock described it as “the most difficult single shot I’ve ever done.” [13]

Albert Whitlock’s matte painting for the final shot.

The final composite shot.

So that’s it. The End. Or is it? The Birds certainly has an unconventional ending, and this is one of the things about it that I love the most. Aside from the psychological resolution to the characters and their relationships, there is no resolution to the story, and no explanation of why the birds behaved as they did. Had Hitchcock ended the film in a more conventional way, both its impact and its subsequent reputation as a “great film” would have been considerably diminished. Indeed, the inclusion of a resolution or explanation would have completely negated what I have argued is the film’s meaning.

In 1963, audiences reacted negatively to the ending. “Was that it?” some were heard to say. Others, as Cinemafantastique notes, “expecting answers to the questions posed by the film, misinterpreted the blank screen as a break in the reel. To avoid confusion come release-time, (assistant editor) Bud Hoffman had Technicolor do an overlay clearly announcing that it was, in fact, ‘THE END.’ As it was too late to add the title to the original negative, the title had to be overlay printed on every existing copy of the film.” This was, moreover, at the insistence of the studio. Thankfully, copies in circulation today (available on home video, for example) do not include this.

American audiences in 1963 were, it would seem, almost as dim as audiences today. They wanted a happy ending — or at least a definite one. And they wanted pat answers. Many of them would probably have characterized themselves, ironically, as “mystery lovers.” The truth is that they could not tolerate mystery. In short, they were a modern audience, meaning an audience shaped by modernity. They didn’t get that they were all Mrs. Bundy, and that The Birds is rebuking them.

Audiences then and now are unaware that this was not how The Birds was originally supposed to end. After the Brenners and Melanie drive away from the farm, Hunter’s screenplay, even in later drafts, goes on for another seven pages. I will not summarize the events in detail, aside to say that Hunter has them driving through Bodega Bay, witnessing the aftermath of widespread carnage. Windows are broken, cars are overturned, and there are several dead bodies. Perhaps the best detail in the sequence is a dead man seen on the side of the road “clutching a television set in his arms.”

And everywhere, the birds are perched. When the car reaches the highway, Mitch really floors it. “Here we go,” he says. The birds immediately take flight, pursuing the car. They begin to divebomb the vehicle’s soft canopy, ripping holes in it. The women become hysterical. The most dramatic moment comes when Lydia cries out at the sky: “‘Dear God. . . dear God. . . please, please, what have we done? Please.’ (and then in anger at the roof and the birds) ‘Can’t they leave us alone?’ (shrieking it) ‘LEAVE US ALONE!’” Eventually, the car begins to outdistance the birds. “We’re losing them,” Lydia says, calming down. The final line of the script belongs to Mitch: “It looks clear up ahead.” Hunter then specifies, “FULL SHOT – THE CAR moving AWAY FROM THE CAMERA FAST into magnificent sunrise over the crest of the hills. Further and further into the distance it goes. FADE OUT: THE END” Hurrah! Our heroes are safe, riding off into a hopeful sunrise.

Ho-hum.

None of this was ever shot, so don’t go in search of “deleted scenes.” (The one scene deleted from the final print, described in part two [2], appears to be lost.) Years later, Hitchcock explained his decision not to film the sequence: “I excluded those scenes because I felt they were superfluous. Emotionally speaking, the movie was already over for the audience. The additional scenes would have been playing while everyone was leaving their seats and walking up the aisles. We used to call these hat-feeling scenes.” What this last comment refers to is that when audiences start to feel like a film has gone on too long, they get antsy and begin feeling the brims of the hats they hold in their laps, waiting for the credits so that they can get up and leave. At least, in the days when people still wore hats (or took them off).

Even decades later, Hunter was bitter about Hitchcock’s decision to cut these scenes. Apparently, the entire reason his script specified that Melanie drives a convertible was to make possible the drama of his final scene, when the car’s canopy is ripped by the birds. In an interview from 1980 (partially quoted in our last installment [8]), Hunter said “I don’t feel the new ending is ambiguous. I feel it is simply puzzling. With such a large question looming, it seems to me the end of the film should have at least been decisive.” Hunter was a talented writer, but he was fundamentally conventional. He wanted a “decisive” ending and definite answers. Somewhere along the way, Hitchcock decided he wanted ambiguity and no definite answers.

The authors of the 1980 Cinemafantastique article offer the following perceptive response to Hunter:

Actually, it is only after you have seen the film a few times that Hitchcock’s ending seems, if not complete, then at least artistically correct. While certainly puzzling, the ambiguity of the final shot may be seen as a thematic element of the film, that facile endings are often misleading in their attempts to pacify audiences. Perhaps more birds will be waiting in San Francisco; or we may assume that what is happening in Bodega Bay — with reports of scattered attacks in the nearby communities of Santa Rosa and Sebastopol – is part of an isolated occurrence, rather than one of world-wide proportions, as du Maurier’s story seems to indicate. Infinitely more valuable than any pellucid denouement The Birds might have offered is the thought that lingers after its final images have faded.

Indeed. And, as I have argued in this series (persuasively, I believe), Hitchcock’s changes to Hunter’s script were motivated, in part, by the desire to make the audience think. By ending the film without any real resolution or explanations, he is signaling his belief that the world is deeply mysterious, far more mysterious than we moderns are willing to admit; that full and final explanations are not forthcoming, nor will they be; and that we are not the masters of our own fate. This is a far more unsettling film than Psycho, which actually featured a definite conclusion as well as a facile psychological explanation for why Norman Bates acted as he did. The Birds is more unsettling because we know, deep down, that what it is telling us about ourselves is true; that beneath the thin veneer of Progress, there is unfathomable mystery and unspeakable horror. We do not like this; we do not want to be reminded of our vulnerability. That the audience resists the film’s conclusion underscores how appropriate and necessary that conclusion is.

* * *

Having now written more than 46,000 words about The Birds, is there anything left to say? By me, at least? Of course. Camille Paglia is quite correct when she notes that “The more microscopically this film is studied, the more it reveals.” [2] [14] Yet commentators on this website have accused me of “overintellectualizing” the film. One opined that “sometimes a story is just a story.” Such comments are useless because they do not actually engage the interpretation. If the reader finds the interpretation implausible, why? And be specific. You don’t need to write 46,000 words in response, but a little more than a dozen might be helpful.

However, it is reasonable to ask if all these “Heideggerean” layers of meaning could really be present in The Birds. After all, it is unlikely that Hitchcock ever read Heidegger. Though I did argue in earlier installments that there is a demonstrable “existentialist” influence on The Birds, the best answer to this objection is to show why it is irrelevant. I never claimed that Hitchcock, or Evan Hunter, intended to inject Heideggerean philosophy into the film. I merely claimed that Heidegger’s philosophy provides us with a powerful tool for interpreting it. I think that I have demonstrated this.

Interpreting a work of fiction is not entirely a matter of trying to identify what its authors’ conscious intentions were. In fact, that is not even the primary concern. As I discuss more fully in part four [4], works of art mean more than their authors intend. Heidegger argues that the meaning of things changes over time. This includes the meaning of films. If this series has at all been a success, The Birds now means more to you than it did before.

So what of COVID-19, about which I have said not a word. The title of this series promises that it will reveal everything you always wanted to know about the virus (but were afraid to ask Hitchcock and Heidegger). What in hell does COVID-19 have to do with The Birds? Well, isn’t it obvious? My suggestion all along has been that the pandemic is a Heideggerean “event.” In part five [5] I argued for the equivalency of the Heideggerean Ereignis (event) and “the apocalypse,” defining the latter as a shift in being or meaning that is abrupt, sudden, and usually unanticipated, not under our control, and radically transformative: once it occurs, nothing will be the same again. The pandemic has shaped up to be exactly that. But this is not so much due to the virus itself, as to its economic consequences and the ways in which the pandemic is being manipulated for sinister, political motives.

Throughout the series, I have dropped hints about this. In part four I quoted the du Maurier story, in which, in the midst of the bird attacks, the main character thinks to himself,

“There’s one thing, the best brains of the country will be onto it tonight.” Somehow the thought reassured him. He had a picture of scientists, naturalists, technicians, and all those chaps they called the backroom boys, summoned to a council; they’d be working on the problem now. This was not a job for the government, for the chiefs-of-staff — they would merely carry out the orders of the scientists.

I then asked my readers if this sounded familiar to them. It does, doesn’t it? In part seven I quoted the original screenplay, in which Mitch and Melanie look out across the bay, just before the birds attack the house. They have the following exchange:

MITCH

(after a long pause) It. . . it doesn’t look very different, does it? A little smoke over the town, but otherwise…

MELANIE

(looking) Even the birds sitting out there. It does look very much the same, Mitch. This could be last week.

MITCH

It may not be last week again for a long long time.

Isn’t this how we all feel? “Last week” for us was early in March, because it was in mid-March that everything changed. Doesn’t it now feel like a lifetime away? Of course, as I was writing this series, the pandemic morphed into the Zombie Apocalypse. The BLM riots occurred, in the US and, surprisingly, in Europe. Looting, burning, the destruction of history. But perhaps worst of all, the lying. And the abject cowardice of our “conservatives” — most of them. “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

Our enemy is an iteration of the modern ideology attacked in The Birds. That will to power that sought to know nature and to master her has now made its ultimate power grab: declaring that there’s no nature at all, only human interpretation, only “construction.” Thus, all differences are only apparent, and manipulable. Underneath all appearances, everyone is the same (but remember to “celebrate diversity”). Equality is the slogan, uniformity is the actual goal. But the human material resists. It still gives rise to peaks and valleys. And the peaks are a reproach to the valleys, so they must be pulled down. Everything must be leveled.

And they are coming for you. Time to start boarding up the farmhouse. Did you get the windows in the attic, Mitch? I got them all, Mother. When do you think they’ll come? I don’t know. Maybe we ought to leave. Not now, not while they’re massing out there. When? I don’t know when. Where will we go?

Where indeed. Soon BLM will reach Bodega Bay. Perhaps it already has. Perhaps The Birds has been declared “too white” (it really is, you know; another reason to love it). Or perhaps the birds themselves have returned to Bodega Bay, in all their fury, and the locals are kneeling to them and washing their talons.

There will soon be no place to go, and everything is moving very, very quickly. “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” The “collapse” many of us thought was coming many years down the road may have arrived much sooner than anyone anticipated. I can hear Mrs. Bundy now: “Impossible! Ridiculous! The very concept is unimaginable! Really, let’s be logical. . .” Of course, that’s what she said about the collapse of the Soviet Union, before it happened. Poor Mrs. Bundy. Poor old gasbag.

In facing this collapse, are there lessons to be learned from The Birds? Yes, there are obvious ones like the importance of resourcefulness, staying calm under fire, and courage. Oh yes, and tribalism (see part seven [7]). The less obvious lessons present opportunities for self-overcoming. We are staring into the abyss. We have absolutely no idea what is coming, and whether it will entail our victory or our destruction. Will savagery be victorious? Will we lose everything we have built? I am optimistic. We need to stay in the house and fight. Eventually, we may have to pile in the car and leave, driving off into the sunrise, looking for a better place. One without. . . ahem. . . birds. But we will live.

That’s my hunch. But we do not know. We are, in large measure, not the masters of our destiny. Now more than ever we realize the truth of Heidegger’s “anti-humanism” (see part four). We realize that we are in the grip of forces we do not fully understand, and cannot control. We can only move forward, straight into that abyss, hoping for the best, and conducting ourselves with honor.

It is terrifying. But isn’t it exciting?

Hitchcock and Hedren in happier times.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [15] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [16] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [17] During the making of the film, the cast and crew threw a thirteenth birthday party for Veronica Cartwright, complete with cake and gifts. Tippi Hedren gave her lovebirds.

[2] [18] Camille Paglia, The Birds. London: Bloomsbury – British Film Institute series, 2020 (1998), p. 2.