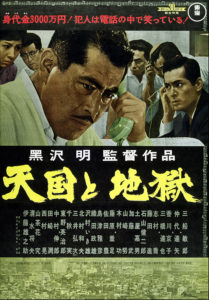

High & Low

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,719 words

Like most Westerners, I got to know Akira Kurosawa through his classic samurai films: Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, Yojimbo, Sanjuro, Kagemusha, and Ran. Thus I was surprised to discover that fully half of his thirty films are actually set in contemporary Japan over the stretch of Kurosawa’s long lifetime (1910–1998). High and Low (1963) is one of the best of these films, along with Drunken Angel, Stray Dog, and Ikiru.

Many of Kurosawa’s most important Japanese films are actually based on stories by Western writers: Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Gogol chief among them. In the case of High and Low, however, the source is a hard-boiled American crime novel: King’s Ransom by Ed McBain (born Salvatore Lombino), who under the name Evan Hunter was also the screenwriter for Hitchcock’s The Birds.

The Japanese title of High and Low is Tengoku to Jigoku, which literally means “Heaven and Hell.” But High and Low is a good title, because the movie is constructed around the contrasts between a modernist mansion of Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) which stands alone on a high bluff overlooking Yokohama, and the crowded, chaotic city below.

There is also a contrast between high and low class, understood here as rich and poor. From the point of view of the poor people of Yokohama, however, it is easy to think of Gondo’s lofty mansion — isolated, spacious, starkly modern, and cooled by breezes — as heaven compared to the cramped, noisy, sweltering hell they inhabit. (Kurosawa loves to portray people sweating, fanning themselves, and huddling by electric fans. He must have hated hot weather.)

But these contrasts are not setting you up for a Marxist narrative about the virtuous poor and their wicked capitalist exploiters. Quite the opposite. High and Low is a portrait of a virtuous industrialist who is targeted for destruction by a nihilistic criminal who hails from the professional rather than the working class and is motivated not by need but by envy and pure malice.

Kingo Gondo is not a steel baron or oil tycoon. He is an executive at National Shoes, which makes women’s footwear. But it turns out there is a heroic and manly way to make women’s shoes. Gondo has worked his way up from being an apprentice shoemaker to being a shareholder and executive. He is hosting some of his fellow executives, who wish to enlist him in a corporate coup against the “old man” who founded the company and is stuck in a rut of making unfashionable “army boots.” Gondo’s colleagues wish to manufacture flashy shoes that are cheaply made. Gondo wants to make more fashionable products, but he feels that selling shoddy merchandise is dishonorable and eventually dresses down his colleagues, then tosses them out.

Gondo then explains to his assistant that he has been planning his own takeover of National Shoes, mortgaging himself to the hilt buying up chunks of stock. All he needs is to complete one last purchase. But before he can dispatch his assistant with a check for fifty million yen, he receives a phone call informing him that his son Jun has been kidnapped and demanding thirty million yen in ransom. (This is thirty times higher than the highest-recorded ransom.) But when Jun walks into the room, Gondo concludes that the call was a sick prank. It turns out, however, that the kidnappers have snatched Jun’s playmate, Shinichi, the son of Aoki, who is Gondo’s driver.

This creates a great moral dilemma. Gondo’s first reaction is that he will not pay. It is not his child, after all. Instead, he will complete the deal that he has staked everything on. Surely the kidnapper will be reasonable and let the poor child go. But no, if Gondo does not pay, the child will die. It is an agonizing choice. If he does pay, the child may still die, the money may never be recovered, and Gondo will almost surely be ruined. Eventually, though, Gondo is persuaded by his wife, his driver, and the police to pay the ransom. It is the compassionate thing to do.

At this point, the movie was nearly half over, and it suddenly dawned on me that the film had not yet left Gondo’s house. Most of it has been shot in his vast and sparsely-furnished living room. Thus far, High and Low has been, in effect, a filmed stage play. But Kurosawa is so virtuosic at creating dramatic tension and coaxing out compelling performances that the result is not static at all. High and Low is not just a well-crafted crime drama that was wildly popular with Japanese moviegoers. It is also an avant-garde cinematic experiment — in fact, a whole series of them — a fact that most viewers are too enthralled to even notice. It really sneaks up on you.

The ransom sequence takes us from the spacious and static setting of the Gondo mansion to a cramped passenger car on a high-speed express train. Yes, the Japanese had them even in the early 1960s. It is an amazingly tense and dynamic action sequence.

The film then switches gears again into a quasi-documentary about the police’s attempts to find the kidnapper and recover Gondo’s money. At this point, some people might feel the movie drags, but I found the meticulous rationality of the detective work fascinating. From the police’s first appearance at Gondo’s house — disguised as delivery drivers in case the house is under surveillance by the kidnapper — they are impressive in their intelligence, sensitivity, camaraderie, and teamwork. It is a wonderful portrait of what is possible in a homogeneous, high-IQ, high-solidarity society — everything whites have lost by embracing diversity. The kidnapper is the police team’s stark antipode: also highly intelligent, but a solitary, sadistic sociopath.

In the last scenes of High and Low, as the police close in on their quarry, the film shifts style yet again into pure German Expressionist horror, then into post-war Existentialism. Caligari meets Camus. This film is truly a descent from heaven into hell.

The ending is happy but haunting. In this case, justice has triumphed, but at great cost. Evil and chaos will always threaten order and goodness. They will always need to be quelled by brave and rational guardians of public order.

High and Low is clearly an anti-Marxist film. Gondo is a self-made man, who rose to his position due to hard work. He was not born to wealth and privilege. His wife does come from a privileged background, and her dowry certainly helped matters, but he had to win her through hard work and character as well. (Her dowry gives her some clout in the deliberations about whether to pay the ransom.) Gondo puts the integrity of his products above the simple pursuit of profit. He is also willing to court financial ruin when he is convinced that paying the ransom is the right thing to do.

The kidnapper is not driven by want, but merely by resentment. His goal is not simply to take Gondo’s money but to humiliate and destroy him. It is clear that his malice is so deep and irrational that no social reform will ever banish it. In fact, the Leftist rhetoric he spouts is simply a tool by which these monsters gain the power to murder millions.

This being a Kurosawa film, vestiges of Japan’s feudal traditions crop up throughout the story. Gondo’s driver Aoki acts like a cringing, servile feudal retainer. This makes Gondo angry. After all, this is modern Japan. Both men come from humble backgrounds. They simply have a business relationship. Why shouldn’t they be on terms of social equality?

But the men are not equal, and the deepest inequality is not financial but a matter of character. Gondo risks his fortune to save the child of his driver. Risking oneself to protect one’s retainers is, of course, the foundation of feudal obligation. Did Aoki understand Gondo better than Gondo understood himself?

The police are faultlessly professional in their dealings with Gondo. One of them confesses a personal prejudice against the rich. But as the detectives observe Gondo’s character — his decision to pay the ransom, his courage, his intelligence, and his unpretentiousness (mowing his own lawn, breaking out his shoemaker’s tools to help modify the briefcases for the ransom) — they are won over, and by the time the ransom has been paid, they have been transformed by sheer admiration into feudal retainers fighting to save their lord from social and financial ruin.

High and Low’s portrayal of a heroic businessman plagued by an envious villain, as well as its celebration of the rationality of the police detectives, could almost spring from the pen of Ayn Rand. Gondo and the detectives represent the highest virtues of bourgeois modernity, whereas the kidnapper represents its deepest vice.

But the film’s depiction of how the charisma of leadership springs from the willingness to risk personal ruin for what is right takes us into the entirely different moral realm of aristocratic honor culture. In truth, Gondo’s argument with his colleagues over lowering the quality of their shoes and then his struggle with himself over whether to pay the ransom are versions of Hegel’s primal duel that stakes life itself over matters of honor and sorts men into two types: masters and slaves.

Kurosawa sees truth in both value systems and uses the tension between them to create powerful drama. He uses the same tension to great effect in 1948’s Drunken Angel, the first of his sixteen films with Toshiro Mifune. Kurosawa uses the conflict between samurai honor culture and Buddhist compassion to similar dramatic effect in Rashomon [1].

High and Low is a masterful fusion of compelling drama, technical virtuosity, and artistic daring. By bringing in deep, serious — ultimately world-shaking — value conflicts, Kurosawa makes high art out of the otherwise low genre of detective fiction. It is one of Kurosawa’s finest works.

The Unz Review, June 29, 2020 [2]

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [3] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [4] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.