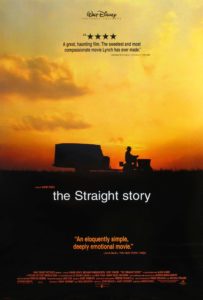

The Straight Story

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,483 words

When I saw Blue Velvet [1] and Twin Peaks, I was convinced that David Lynch is an essentially conservative and religious filmmaker, with a populist and mystical bent. Arguing that thesis was an uphill battle as his work got increasingly dark in the nineties. Many people interpreted Lynch’s portrayals of quirky, salt-of-the-Earth white Americans as parody, his mysticism as arbitrary weirdness, and his depictions of evil and violence as inconsistent with having a conservative and religious moral center. (They’d probably argue the same thing about Flannery O’Connor as well — and just as wrongly [2].)

Then came 1999’s The Straight Story, which reprises all the wholesome, life-affirming, and sentimental elements of Lynch’s earlier works without the darkness, terror, and demonic evil. The Straight Story is so wholesome, in fact, that it was rated G and released by Disney.

The Straight Story is the story of Alvin Straight (1920–1996), a small-town Iowan who at the age of 73 decided to visit his stroke-stricken brother 240 miles away in Wisconsin. What makes Straight’s journey interesting is how he did it. Alvin didn’t have a driver’s license because his eyes were bad. So he put a hitch on his riding lawnmower, hooked up a small trailer full of fuel, food, and camping equipment, and set out for Wisconsin, driving five miles an hour along the side of roads and camping in the fields at night. All told, the journey took six weeks, including breakdowns and repairs. (Then a nephew drove Alvin and his lawnmower back home.)

The basic characters and outline of The Straight Story are based on fact, but many of the details strike me as pure Lynch. Lynch did not, however, write the screenplay, although it was co-authored by his longtime collaborator (and third wife) Mary Sweeney. Perhaps Lynch was attracted to the project because it was already sufficiently “Lynchian.”

The entire cast of The Straight Story is white, and they are Lynch’s trademark quirky, good-hearted, small-town Americans.

Alvin Straight is beautifully portrayed by Richard Farnsworth, who was nominated for the Best Actor Oscar. Alvin is a soft-spoken, gentle man who stubbornly tries to cling to his independence and dignity as old age and illness strip them from him. Farnsworth lived his role. He was suffering from metastatic prostate cancer while filming and took his life the next year at the age of 80. He brings Alvin to life with warmth and gentle humor. He is particularly powerful when relating sad memories, such as his daughter Rose’s loss of her four children, and his terrible guilt about accidentally killing a member of his own unit during World War II. But to me, the most touching scene is simply watching Alvin’s face as he silently overhears the bad news that his brother Lyle has had a stroke.

Sissy Spacek is wonderful as Alvin’s slightly “special” (perhaps autistic) daughter Rose. Everett McGill, of Dune [3] and Twin Peaks fame, plays Tom, a John Deere salesman. Harry Dean Stanton (Wild at Heart [4], Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Inland Empire, Twin Peaks: The Return), has an almost wordless role as Alvin’s brother Lyle. The rest of the cast are local Midwesterners, and they are uniformly excellent.

As Alvin makes his journey, he dispenses bits of wisdom to the people he meets.

In one scene, he camps with a surly teenage runaway girl who slowly warms to him. Alvin intuits that she is running away because she is pregnant and urges her to return home. She can only think of the enmity of her family, but Alvin suggests there is strength in family as well, using a very concrete and primal metaphor: the fasces. An individual twig can be broken, but tie them together in a bundle, and they become strong. The next morning, the girl is gone. But she communicated her decision by leaving a bundle of sticks.

In another scene, Alvin and a fellow WWII veteran share painful memories of friends they lost. But the Germans are not dehumanized. In fact, Alvin mentions that at the end of the war, “We were shooting moon-faced boys.” The war is simply presented as a senseless waste of life, which it was.

The Straight Story is a warm and sentimental portrait of the American Midwest and its people. Lynch filmed it on location, on the actual route Alvin took. He also filmed every scene in the order in which it appears. In short, Lynch took Alvin’s journey. The Straight Story contains Lynch’s most beautiful nature photography. It is set during harvest time, with rippling fields of ripe grain, vivid sunsets, and autumn leaves, all suffused with gold.

Yet, despite its seeming straightforwardness, Lynch characterized The Straight Story as his “most experimental movie” thus far. To my eyes, it is an experiment in being naïve and spontaneous. One scene plays gently with movie conventions. We see Alvin driving his tractor down the road away from us, then the camera slowly pans up to the beautiful blue sky — then slowly back down to Alvin, who, of course, has only gone a few more feet. Whenever I saw this scene in a theater, it always provoked gales of good-natured laughter, because if this were any other movie, and Alvin were riding anything other than a lawnmower, he would be just a dot in the distance.

There are many Lynchian touches beyond the affectionate portrayals of quirky and sometimes grotesque Midwesterners. Lynch’s trademark depiction of technology as an ominous and dehumanizing force — using loud mechanical thrumming and screeches — is used to good effect with a grain elevator at night and also huge semi-trucks looming over Alvin and his vulnerable, hobbit-scale technology.

When Alvin’s brakes give out and he comes hurtling down a hill, the sequence is viscerally real. Like Alvin, we feel out of control and jarred to our bones. Yet the backdrop of a burning building gives the scene an apocalyptic and surreal quality.

When Alvin sees a deer killed by a hysterical female motorist, he of course uses it to replenish his supplies, cooking it over a fire — while surrounded, somehow, by lawn statues of deer out in the middle of nowhere.

Lynch is a director who believes in the reality of the supernatural. (See, especially, my review of Lost Highway [5].) There is only one scene that suggests such powers in The Straight Story, and it is masterfully handled. The real Alvin Straight’s tractor conked out just short of his brother’s house, and he was towed the rest of the way by a local farmer. In Lynch’s film, when Alvin’s tractor conks out, a man on a much bigger tractor pulls up.

We see the whole thing from a distance, too far to clearly hear the dialogue. Lynch has used the same technique in two earlier scenes of the movie. We also get no closeup of the farmer’s face. He seems to simply suggest that Alvin try starting his tractor again, and lo, it works. The big tractor then pulls in front and leads Alvin to the driveway of his brother, pointing to the turn, then continues on with a wave goodbye. The big tractor/little tractor contrast, the uncanniness of the distance, and the lack of any explanation for why Alvin’s tractor started again all suggest a bit of well-deserved divine intervention, after a wonderful demonstration of American ingenuity, independence, and self-help.

Another outstanding feature of The Straight Story is longtime Lynch collaborator Angelo Badalamenti’s beautiful score, which is the best thing he has composed since his iconic music for Twin Peaks.

The Straight Story received universal acclaim from critics and Lynch fans, but it did not break out of those circles to become a box office success, nor is it well-represented on home video. The DVD has no extras, and the only Blu-ray I could find is Japanese. The CD of the soundtrack and the book of the script are also long out of print. The Straight Story is long overdue for a critical reappraisal — and a Criterion Collection Blu-ray with all the trimmings — for it is truly one of Lynch’s finest works.

The Straight Story is a film about American pluck and ingenuity, the importance of family, the necessity of forgiveness, and growing old with independence and dignity. If you have conservative and populist tastes, love Americana, and are looking for a wholesome, artful, and deeply touching story you can enjoy with your whole family, see The Straight Story. It is the last film most people would expect from David Lynch, but it comes straight from his heart.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [6] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [7] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.