Saint Louis: From an Anti-White Point of View

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,316 words

Walter Johnson

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

New York: Hatchett Book Group, 2020

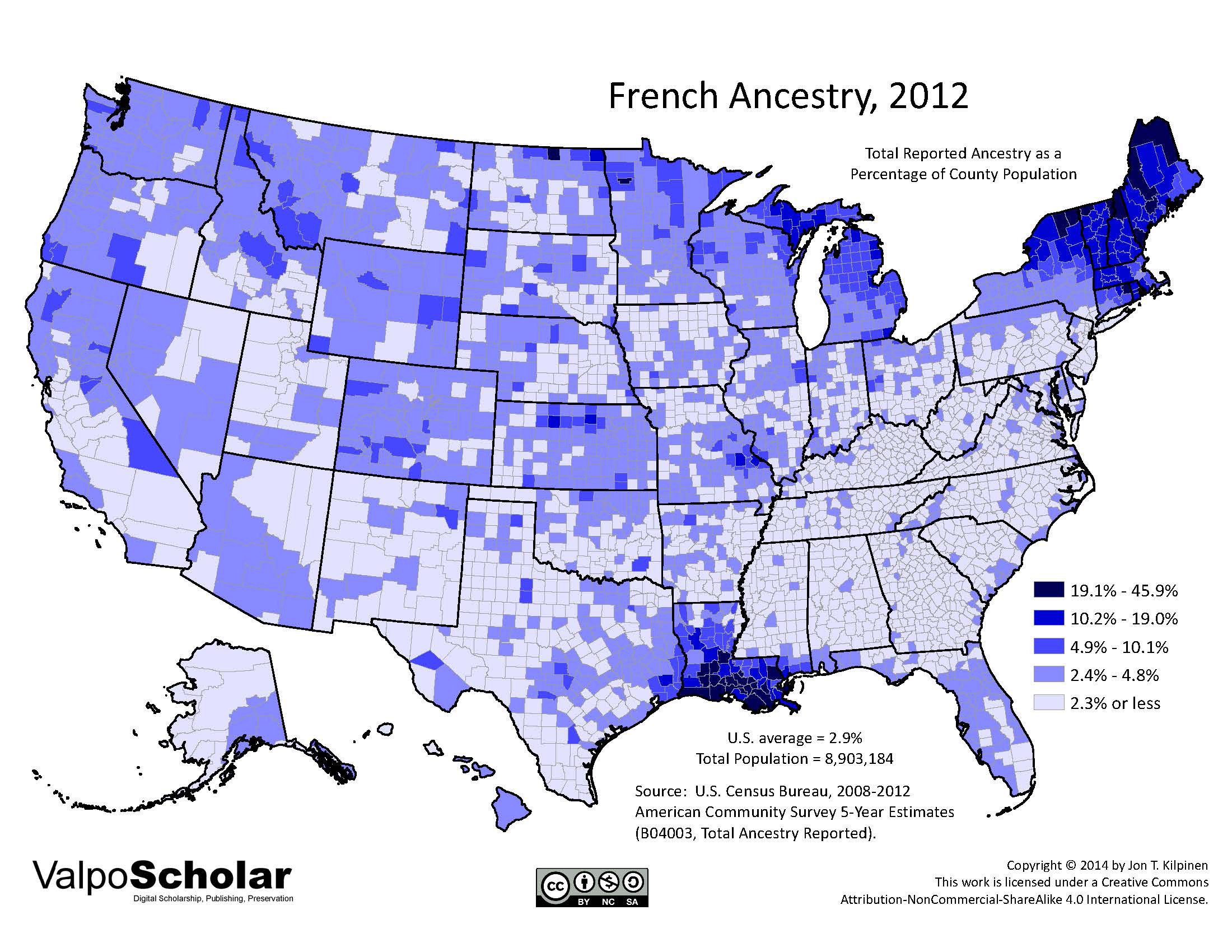

New York is a city that is in its own category. Go north, and one is “Upstate” — across the Hudson, and one is in “Jersey.” From the perspective of New Yorkers, Upstate and Jersey are like foreign lands. On the other hand, Saint Louis, Missouri, is All-American. Its culture is not only reflective of its surrounding hinterlands, one can see that the people of the region are by and large still mostly descended from the French habitants and Anglo-American pioneers that founded the place.

County-level map of population that specified French ancestry in 2012

The distribution of the Missouri French dialect [1]

Walter Johnson, a white Missourian, has written a good history of the city from the politically correct point of view of a weeping white liberal and there is plenty of judgmental anti-white vocabulary throughout the book. Indeed, he is utterly hostile to the white working class and the labor movement throughout the book. I left out discussing Johnson’s stories in this review of the various strikes by the white Labor Movement in Saint Louis since such items are white people’s problems and racial conflict trumps all. Nonetheless, if one ignores the nonsense, there is much to learn in this book.

The Outpost of the Empire Builders

Sometime around 1000 AD, Indian tribes which were likely the ancestors of the Mandans, Arikaras, and Hidatsa created a civilization that built earthen pyramids in the greater Saint Louis area — specifically, the eastern bank of the Mississippi River in Cahokia, Illinois, and its surrounding area. That civilization collapsed mysteriously in the 1300s, so when a French explorer named Pierre Laclède and his stepson Auguste Chouteau went up the Mississippi from New Orleans to set up a trading post, the place was mostly wilderness.

Laclède and Chouteau founded the town on a high bluff near the river, and that’s made all the difference. The area is called Saint Louis Region rather than, say, Greater Alton, Illinois, because the land where the Mississippi meets the nearby Illinois or Missouri Rivers flood often enough to give anyone there a severe economic setback from time to time.

Saint Louis is the dominant city in the region because it’s built on an area just high enough to avoid flooding. Alton gets flooded.

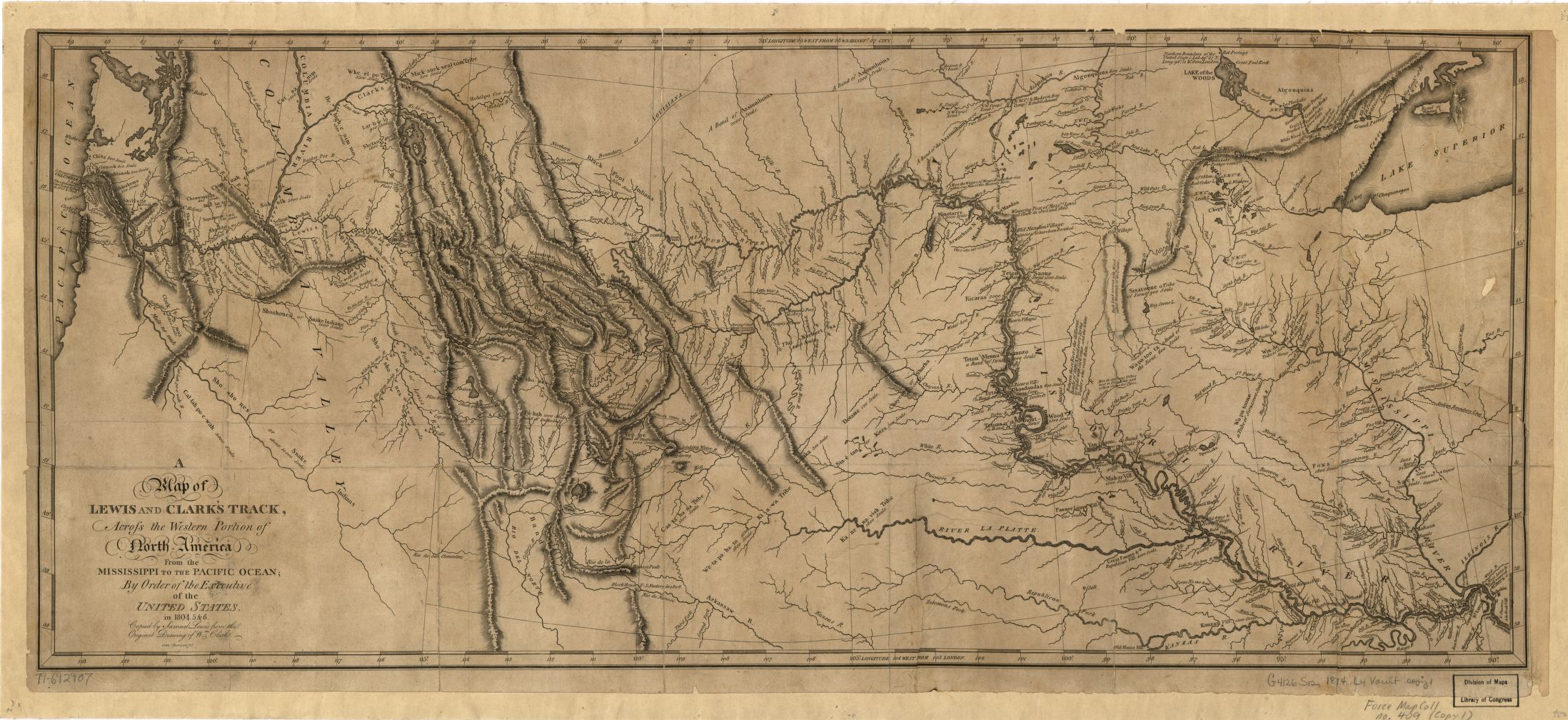

Auguste Chouteau was the top merchant in the region when Captains Lewis and Clark arrived in the area to launch their voyage of discovery. These men were all part of a trend. They were empire builders, and Saint Louis turned out to be a key base in American imperial expansion. Military expeditions were launched from the nearby Jefferson Barracks, and forward operating bases at the end of the Missouri watershed were supplied from Saint Louis by military contractors like Chouteau. Military contracting was critical to the economy. It is so crucial that two of Saint Louis’s suburbs are named for one such contractor — Captain John O’Fallon, a veteran of the War of 1812 and early settler. The defense industry is still a big part of Saint Louis’s economy.

Saint Louis was the starting base for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

One of the empire-builders of Saint Louis was Thomas Hart Benton (1782 — 1859). Benton was born in North Carolina and served in the War of 1812 and then became a US Senator for Missouri. As a young man, he was involved in duels and other sorts of indiscretions one does when young. These indiscretions also led to personal problems with the future President Andrew Jackson. However, as Jackson’s and Benton’s respective careers took off, they set aside their differences and put themselves to work for the good of their people.

Both President Jackson and Senator Benton were national populists and empire builders. Benton, in particular, represented the “white man-ism” of the Free Soil Party that made inroads in the North just prior to the Civil War. Benton endorsed a form of the Homestead Act decades before the Homestead Act actually passed.

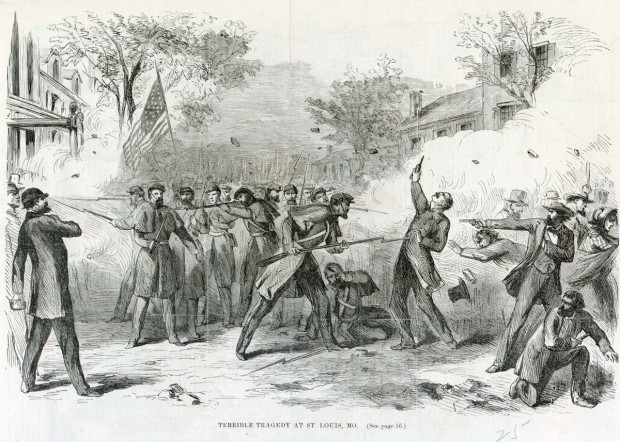

Benton died as the events that brought the Civil War came to a head and Saint Louis was considerably divided politically between North and South. Missouri was a slave state, with a notable population of Southerners. However, many of the Southerners were “white man-ist” Union men who hated the slave aristocracy. Saint Louis also had a considerable population of Yankee and German immigrants. One such Yankee was Union General Nathaniel Lyon (1818 — 1861). He and another German Union officer Franz Sigel organized a pro-Union militia and kept Saint Louis on the Union side. Shortly thereafter, Union general John C. Frémont’s artillery chief Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Weydemeyer organized the defenses of Saint Louis.

The politics of the Union men of Saint Louis must be discussed. Weydemeyer and Sigel were Communists who translated and distributed the works of Karl Marx, yet they still fought side-by-side with U.S. Grant and Nathaniel Lyon, who were native-born American Yankees with roots in Connecticut. During the early days of the Civil War in Saint Louis, Grant and Lyon’s Commander was a half-French half-Southerner John C. Frémont.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Saint Louis was a battleground.

The enlisted men Grant, Lyon, Weydemeyer, and Frémont commanded were ordinary pro-Union whites with German, French, and Anglo-American backgrounds. What held this group together was the overlapping metapolitical ideas of Thomas Hart Benton’s national populism, the Free Soil Party, the Labor movement, and a shared racial sense of imperial destiny.

While some of the Union men in Saint Louis were radicals to the point of being Marxists, most of them adjusted their attitudes after the Civil War. For example, the Leftist Anzieger paper started to editorialize for segregation after the war. With that in mind, one can conclude that the Leftist insane asylum in American politics appeared after the start of the Second Great Awakening, became attached to the abolitionist movement, and then died away as Civil War veterans started to realize that blacks were a dangerous menace. By the 1870s, the Saint Louis Germans were voting for pro-white laws in the same way the Anglo-Americans did.

One Saint Louis German — an exile from the Revolutions of 1848 and thus a former radical — named Carl Schurz became part of the “liberal Republican” faction in the 1870s. This faction urged an end to Reconstruction and amnesty for former Confederates. He’d go on to support white interests throughout his career. He encouraged his fellow politicians to not expand into the Pacific in a way that would eventually make Asians and Pacific Islanders citizens, but he was ignored. This is unfortunate; Hawaii is a polity with as tense a racial political climate as a city in the Mainland after a race riot.

Anti-Blackness

Walter Johnson identifies a longstanding cultural aspect of Saint Louis politics that he calls “anti-Blackness.” There are two forms of anti-Blackness on the part of whites in America. In the South, especially the Deep South, there is the patronizing anti-Blackness of the plantation model. There, blacks have the security of a place in the system and they are managed for a positive economic effect. Move northwards along the Mississippi River, and anti-Blackness shifts to a deeper hostility.

Part of the Southern model of anti-Blackness is to ship any problem Negro to the North. The result of this is that Northern cities acquired an African criminal caste that took over neighborhoods and became a constant riot threat. Indeed, as this article goes to print, Minneapolis, a later victim of the Sub-Saharan “Great Migration,” is suffering the effects of black migrants.

Johnson shows that Saint Louis started to suffer from black migrants as early as the 1830s. He describes a number of antebellum high profile cases of blacks that were lynched or convicted in an emotional trial. The story then is the same as now; a criminal black that “didn’t do nothing” ended up being an example of the Sub-Saharan’s inability to contribute to civilization. In this book, however, each Sub-Saharan that “didn’t do nothing” is a “saint.” Johnson also describes the East Saint Louis riots and the slide of that formerly nice city into Zaire-like ruin. He blames the whites, of course, and absentee capitalists are a big part of the blame, but the proximate cause of the disaster is the collective decisions of Sub-Saharans as a group bringing all local areas to ruin.

The Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project was a big housing give-away to blacks moving to Saint Louis from the South in the late 1940s. There’s a great deal of literature and a good documentary on the housing project, but they all fail to state the central truth: Africans cannot maintain white civilization even when a part of that civilization is literally given to them.

It is likely that because Saint Louis was the first city to suffer from the effects of the movement of Africans from the plantations of the Deep South (indeed, several “civil rights” cases originated in the Saint Louis region) that it has produced a group of serious metapolitical thinkers which created the Barry Goldwater-style New Right in the early 1960s. These metapolitical leaders held the line — to some degree — against the gains of “civil rights,” and their ideas laid the intellectual groundwork for the final defeat of the Soviet Union. These thinkers include Gerald L. K. Smith, who published a newsletter from a printing house on Grand Avenue called The Cross and the Flag; the Reverend John A. Stormer, who wrote the anti-Communist classic None Dare Call it Treason from the suburb of Florissant in 1963; Phyllis Schlafly, who single-handedly stopped the Leftist Equal Rights Amendment and wrote the book A Choice, Not an Echo in 1964; and Rightist Pat Buchanan, who worked for the Saint Louis Globe-Democrat prior to joining the Nixon administration.

Urban Renewal in Saint Louis

Bricks in old inner-city houses are so valuable that they are salvaged and used to build fashionable McMansions in newer and wealthier cities like Houston. By the 1920s, Saint Louis had a considerable amount of old buildings that were occupied by Sub-Saharans who’d turned them into slum neighborhoods. As a result, city planners carried out an urban renewal project. The first big effort was to demolish the slums along the riverfront. Until 1964, this area was a giant parking lot, until it was turned into the great engineering and architectural triumph of the stainless steel Saint Louis Arch. The interstate also was a big boost to the economy and a way to carry out African removal.

In Saint Louis, the southern part of the city and suburbs are mostly whites; blacks are located in the northern region as well as East Saint Louis.

Johnson describes the workings of the corporate giveaways and other problems in Saint Louis. Indeed, Saint Louis is a city in the Rust Belt, and it is suffering from the same sorts of problems that plague every town from Pittsburgh west to Kansas City, to include radioactive waste illegally dumped. The failure to protect the humble factory jobs of America and allow them to be shipped to China has been a terrible problem. Financial desperation makes racial matters more difficult to manage than they already are. Because corporations headquartered in the Saint Louis region are often not taxed as fully as they should be, local governments must squeeze the population that has a less powerful voice to make ends meet.

The mass shooting of Kirkwood, Missouri government officials in early 2008 by the Sub-Saharan Charles “Cookie” Thornton is given much space in this book. The author gives Thornton a great deal of sympathy. However, Thornton’s rampage is really a further reason for building the white ethnostate rather than yet again bending the knee to blacks. Thornton couldn’t follow the basic rules of contracting in Kirkwood; he incurred fines, failed to pay them or adjust his behavior, and sued the city and lost. He even assaulted one of the city officers. This poor behavior ensured he wouldn’t get business from the city. Many white businessmen suffer setbacks — none go on a shooting rampage.

Johnson also describes the Michael Brown shooting, but only from the mainstream narrative (i.e. Brown “didn’t do nothing” but walk down the street before he was shot with his hands up). This narrative leaves out considerable details of the story. The truth is that Brown strong-arm robbed a store, and was walking down the middle of the street high on THC where he was confronted by policeman Darren Wilson for jaywalking just around the same time the police were informed of the robbery via radio. Brown charged Wilson, and Wilson shot Brown while he was being assaulted. The police carried out a full investigation, and eventually, Wilson was exonerated by a grand jury.

There is a more cynical reason for why the Michael Brown case occurred. It was likely hyped by the mainstream media and Obama administration to rally blacks to the Democratic Party for the 2014 mid-term elections. The same thing occurred in the 2012 election year with Travon Martin, and again in 2016 with the start of the Black Lives Matter movement. In 2020, the media and Democratic Party establishment hyped the George Floyd case.

The Broken Heart of America is quite informative, although anti-white, but my final comment is that of deep concern. Johnson insists that one of Saint Louis’s oldest and funniest traditions, the Veiled Prophet parade, is some sort of “white supremacist” KKK supporting event.

It’s not. It’s just a parade.

What Johnson is doing is deconstructing and delegitimizing white traditions.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [2] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [3] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.