How Plessy v. Ferguson Came About

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 1,629 words

1,629 words

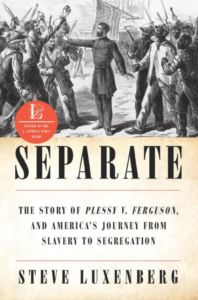

Steve Luxenberg

Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, And America’s Journey From Slavery to Segregation

New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019

Steve Luxenberg is a Washington Post associate editor and protégé of the Watergate reporter Bob Woodward. In 2019, he published a book called Separate, which describes the characters and circumstances involved in the legal case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which affirmed that segregation was constitutional.

Like all books related to “civil rights,” this book suffers from the flaw of not seriously looking at the reasons why so many whites would be keen to keep themselves and their families as far apart from Sub-Saharan Congoids as possible. However, there is still much to learn. For example, Luxenberg shows that some form of the “woke” insane asylum existed as far back as the 1830s.

Segregation, called Separation in the nineteenth century, first became an issue in the Free Soil northern United States almost as soon as the steam engine made public transportation cheap, routine, and essential. One can say that segregation started in Boston. Even the Abolitionists’ famous Token Negro, Frederick Douglass, was forced to go to the “Jim Crow car” by a mean ol’ white conductor.

Separation was not an issue in the South before the Civil War. In a counter-intuitive way, slavery encouraged an intimacy between the two races. Plus, slave owners liked to have their valet or handmaid around. Separation migrated to the South from the North after slavery ended. Luxenberg doesn’t mention the fact that “Jim Crow” Separation laws didn’t exist in the South until a generation after Reconstruction ended.

The book’s narrative centers around three people:

Associate Justice Henry Billings Brown (1836 — 1913). Brown was born in Massachusetts of Yankee/Puritan heritage but moved to Michigan where he became a Federal Judge. He married the daughter of a wealthy man and didn’t serve in the Union Army during the Civil War. Brown wrote the majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson that affirmed segregation.

Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan (1833 — 1911). Harlan was from a prominent Kentucky family. He joined the Union Army during the Civil War and rose to the rank of colonel. He was originally a pro-slavery Union man, but later he became a Republican who deliberately courted black votes in his unsuccessful attempt to become governor. Because he was a Republican Southerner, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him to the Supreme Court to spur on national unity. Harlan wrote the dissenting opinion on Plessy v. Ferguson.

Albion Winegar Tourgée (1838 — 1905). Tourgée was a lawyer who served as a First Lieutenant in the Union Army. He was badly injured by a wagon wheel that flew off its axle during the retreat from Bull Run. This injury caused him constant pain and shortened his life. He would serve as a judge in the Reconstruction government of North Carolina. Tourgée was also a bestselling novelist. Unlike most of the other Yankee Carpetbaggers that served in the South after the Civil War, Tourgée was not disillusioned by the experience. He remained a staunch lifelong “civil rights” advocate. It was he who set up the Plessy v. Ferguson case and argued it before the Supreme Court.

Barratry

Plessy v. Ferguson was a case that was deliberately arranged to test the separation/segregation laws in public places such as trains that were coming online across the United States in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. Such stylized cases are part of a legal trick known as barratry.

The case centered on the arranged arrest of Homer Plessy, a mostly white, mixed-race French Creole from New Orleans. His rival was Judge John H. Ferguson, a Yankee who married into a prominent Pennsylvanian abolitionist family who moved to New Orleans after the Civil War. Judge Ferguson ruled that segregation was constitutional in a lower court ruling. He became the defendant in the Supreme Court trial.

Suffice to say, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was a pro-white victory that allowed separation/segregation. However, nobody recognized that the case was a landmark case until it was cited as precedent in many other separation cases. At the time, the case was not remarked upon by most newspapers. Segregation remained fully in force for the next three generations.

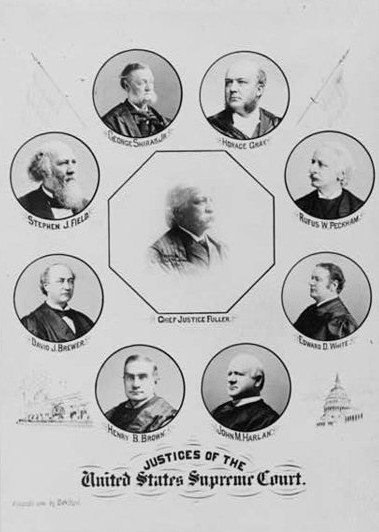

The Supreme Court that decided Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

Critical Thinking

I remain utterly baffled as to why so many whites look upon the pro-white, pro-segregation Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) as bad, and the pro-African, anti-segregation Brown v. Board (1954) as good, when the ramifications of each case were so wildly different and are so universally known. During the Segregation Era of 1896 until 1954, the United States went on a period of massive economic, military, and cultural expansion. After segregation ended, white Americans moved Sub-Saharan Congoids from the margins to the center of American culture. America’s civic religion became Negro Worship. Thus cities burn, whites flee, crime is ubiquitous, and everyone knows the source of the problem, but nobody can say that Africanization and desegregation are the causes without receiving lots of social scorn and obloquy.

It is also made clear in this book, in a between-the-lines sort of way, that the anti-slavery agitation of the North prior to and during the Civil War was a form of Yankee identity politics. Prior to the Civil War, North and South vied against each other over whose descendants would settle the new territories in Kansas and beyond. Yankees were able to create a series of interlocking moral causes — strong national government, abolitionism, union, free soil, etc. — that unified the people of the North so they could win a titanic and bloody struggle. After the conflict was over, Yankees like Judges Ferguson and Brown stopped caring about Congoids. Cynically, one can argue that Yankees used the Negro as a tool to gain the Western Territories for themselves and their posterity over the Southerners and seize a lifetime’s worth of control over the federal government. They then dropped the Negro as soon as they had achieved their goals.

Another concept that should be highlighted regarding this book is that Supreme Court cases that validate existing social norms don’t cause trouble, but ones that overturn the norm and/or bypass the legislatures are disasters. For example, the famous Dred Scott decision overturned Northerners’ Free Soil efforts, which helped bring about the Civil War. Brown v. Board (1954) exposed white children to dangerous Sub-Saharans in school. This damaged education ever afterward and led to the white flight. Roe v. Wade (1973) led to the social disorders surrounding abortion and the Culture War of the 1970s and 1980s.

There is also a long term danger in arming and deploying men as soldiers that are not of one’s race. Homer Plessy was from the community of mixed-race people who had lived in New Orleans since the time of the French colonial settlements. They’d never been slaves — some even owned slaves — and their militia was employed by Andrew Jackson in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans against the British.

A little military service goes a long way, and being the descendants of veterans of a famous battle also goes a long way. It was the French Free People of Color who were most willing to go along with Albion Tourgée’s desegregation schemes. Had the community of Free People of Color been small and disconnected from any other African group, they’d be as beloved as Gurkhas in Britain, but this isn’t the case. New Orleans’s mixed-race Free People of Color group is connected to America’s wider Sub-Saharan population. That population has historical grievances against whites and they are dangerous to themselves and others.

One thing about Judge Harlan. He wrote the dissenting opinion on Plessy, but he worked against non-white immigration and non-Nordic immigration his entire life. One thing I’ve noticed since becoming a white advocate is that white supporters of one race, like Harlan supporting Negroes, often have a deep antipathy towards some other group. It is a thing to keep in mind when white advocates get involved in lawmaking in the future. Such people can be available for deal-making and compromise.

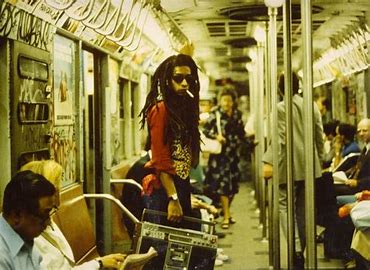

After segregation ended, public transport became dangerous. In New York City in the 1980s, Africans routinely mugged white commuters in New York City and made the place unpleasant.

The Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. probably plagiarized or was told to say by his Jewish handlers that “[he was] convinced that men hate each other because they fear each other. They fear each other because they don’t know each other, and they don’t know each other because they don’t communicate with each other, and they don’t communicate with each other because they are separated from each other.”

Indeed, the book under review starts off with this passage, and King’s drivel was used to fight segregation in the 1950s, but like all things related to “civil rights,” the data is misread. Segregation came about because the white and Sub-Saharan races were communicating and did know each other. Whites understood then and still know now that blacks are dangerous. Segregation keeps the danger down and civilization on track.

It should be pointed out that desegregation as a policy could only be enacted after the private automobile and a large road network came online. A desegregated public transport system is a dangerous place. Africans on public transportation are unpleasant, loud, menacing, and rude. Desegregation should thus be seen as a luxury requiring private transportation and large public prisons where Sub-Saharans can be warehoused.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [1] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [2] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.