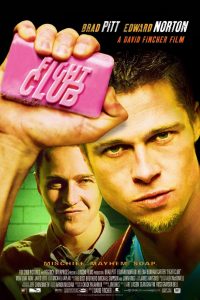

Fight Club

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,005 words

Note: These are notes for a lecture on Fight Club given on October 25, 2000 in an adult education course called “Philosophy on Film.” For a fuller interpretation of Fight Club, see Jef Costello’s “Fight Club as Holy Writ [1].”

What’s philosophical about Fight Club? Fight Club belongs alongside Network [2] and Pulp Fiction [3] in an End of History film festival, because it beautifully illustrates ideas about human nature, history, and culture from Hegel and Nietzsche — especially as read through the lenses of Alexandre Kojève and Georges Bataille.

Prehistoric society is relatively egalitarian and focuses on the cycles of nature and the necessities of life. Hegel held that linear history begins with men risking death in duels over honor, which spring from the demand that one’s sense of self be recognized by others.

The struggle over honor has winners and losers. Its outcome reveals two kinds of men. The master values honor above life. The slave values life above honor. In terms of Plato’s division of the human soul into reason, spiritedness (thumos), and desire, the master is ruled by spiritedness (which is intrinsically connected with honor) whereas the slave is ruled by desire.

The struggle over honor gives rise to class structures and class struggles. The ruling class enjoys leisure, which gives rise to the whole realm of high culture, which is driven by the quest for self-knowledge.

The truth about man, though, is somewhat anticlimactic. Mankind has created art, religion, and philosophy, and endured untold suffering in uncounted wars and revolutions, only to discover that. . . we are all free and equal, which is basically how we lived before history.

When we learn the truth about ourselves, history and culture are no longer necessary. When we are all free to pursue our own aims, history and culture will be displaced by mere consumption, the satisfaction of desire, which in a sense is a return to prehistory. Thus the end of history in Hegel’s sense brings about the rise of Nietzsche’s “Last Man,” who believes that there is nothing higher than himself and his petty pleasures.

The protagonist of Fight Club, played by Edward Norton, is a man with no name. (He is called Jack in the script, but Jack is a name he adopts from a series of pamphlets about diseases.) He is Everyman. He is the Last Man. He works at a sociopathic corporation. He lives in a condo. He has no apparent religious convictions or cultural interests. He buys clothes and furniture, always with the question, “What does this say about me as a person?” He is single and appears to be celibate. He’s free, equal, and has plenty of money to buy stuff. But he feels empty inside. He can’t sleep at night, and you know how crazy that can make you.

Everyman seeks out meaning by attending support group meetings under fake names and false pretenses. He doesn’t seem to have much truck with the forms of spirituality these peddle, but he does find opportunities for genuine emotional catharsis, which help him sleep at night. Unfortunately, another faker has the same idea: Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter). Her presence causes our hero to freeze up.

Marla’s intrusions drive Everyman to take refuge in an all-male support group. This is significant. History begins not just with isolated men battling for honor, but with bonded male groups, Männerbünde, fighting over honor.

Unfortunately, this particular group is called Remaining Men Together. It’s for testicular cancer survivors. Emasculated men hugging each other and crying will not restart history. In fact, the group is pretty much a microcosm for everything wrong with the modern world, which would prefer that all men be emasculated, weepy huggers. But it does point to the next step Everyman needs to take.

On one of his business trips, Everyman meets Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt in his most charismatic role). Everyman is a prisoner of the modern world, but he feels above it. He is like a cow shuffling down a chute in a slaughterhouse who feels he is the master of the situation because he keeps up a constant stream of ironic smart-assery. Tyler is genuinely free of the producer-consumer system: He buys his clothes from thrift stores (at best), squats in an abandoned building, and has his own business (he manufactures and sells soap).

Everyman, however, is a Consumer in the hands of an Angry Author. And the Author dictates that Everyman be stripped of all his worldly possessions, because “the things you own, they end up owning you.” Then he must be delivered to Tyler Durden, for a new beginning. First, Everyman learns that his luggage has been seized and destroyed because it vibrated. Then, he returns home to find that his condo has been incinerated. He needs a place to stay. Fortunately, he has Tyler’s number.

Cut to Lou’s Bar, where Everyman and Tyler are drinking and bonding. At the end of the evening, Tyler asks Everyman to hit him. It is a rather shocking suggestion. Neither man has ever been in a fight. Neither man has been tested. Neither man knows how far he would go to win. Would he risk life itself for victory? If so, he is what Hegel called a master. If he is willing to accept dishonor to avoid death, he is a slave. Of course, at this point, neither man is willing to risk death. Until now, they haven’t even been willing to risk a bloody nose.

After they fight, Tyler and Everyman enjoy a kind of post-coital bliss, then retire to Tyler’s place: a crumbling mansion where he squats. It is as if fighting is an initiation into a new world where bourgeois values of comfort and security no longer matter.

Tyler and Everyman have their fights in front of other men, who naturally want to join in. That’s how Fight Club is formed. Fight Club is a Männerbund. It is structured as a secret, initiatic society. It produces a change of consciousness. “Who you were in Fight Club is not who you were in the rest of your world. You weren’t alive anywhere like you were alive at Fight Club. But Fight Club only exists in the hours between when Fight Club starts and when Fight Club ends.”

Fight Club also transforms values. “After a night in Fight Club, everything else in your life gets the volume turned down. You can deal with anything. All the people who used to have power over you have less and less.” Fight Club breaks the hold that bourgeois society has on us, which springs from a willingness to endure routine forms of dishonor and degradation in exchange for comfort and security.

Not every initiation in Fight Club involves combat, but all of them involve risking death. For instance, one rainy night, Tyler lets go of the wheel of a stolen car, crashing it. When he and the rest of his party crawl out of the wreckage, he whoops: “We just had a near-life experience.” One cannot really live until one puts aside the fear of death and the desire for comfort, security, and control that are at the foundation of bourgeois society.

As Tyler puts it, “self-improvement is masturbation. Self-destruction is the answer.” The self that must be destroyed is the bourgeois self, the rational producer-consumer. That self must be destroyed so that a higher self may be born, which is, of course, self-improvement in a deeper sense.

Tyler understands that an encounter with death forces one to take life seriously. Modern society is masterful at reducing risks and keeping death at bay. Thus it deprives people of opportunities to really come to grips with their mortality, shed illusions, and live life more seriously.

One night, Tyler demonstrates this by pulling a gun on a convenience store clerk and telling him he is going to die — unless he stops wasting his life as a convenience store clerk. It is an utterly brutal and terrifying encounter, but Tyler thinks he is doing the man a favor: “Tomorrow will be the most beautiful day of Raymond K. Hessell’s life” — because of his brush with death at the hands of a gun-toting maniac.

Tyler practices similar tough love with his own friends. One day, he kisses the back of Everyman’s hand then dumps lye on it, causing an excruciating chemical burn. Again, his motive is to force a transformative confrontation with death: “First you have to give up. First, you have to know — not fear, know — that someday, you’re gonna die. It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

When the ordeal is over, Tyler says “Congratulations. You’re a step closer to hitting bottom.” This is the language of Twelve Step programs. Addiction is sustained by self-deception. Hitting bottom is when the consequences of addiction are so catastrophic that one can no longer evade the reality of one’s situation. One confronts it in a moment of clarity, at which point one may embark on the road to recovery.

One of the illusions Tyler is concerned to dispel is the idea of divine providence: “You have to consider the possibility that God doesn’t like you. He never wanted you. In all probability, he hates you. This is not the worst thing that can happen. . . We don’t need him. Fuck damnation. Fuck redemption. We are God’s unwanted children. So be it!”

Tyler’s rationale for this line of attack is explained earlier, when he says “our fathers were our models for God. And, if our fathers bailed, what does that tell us about God?” If God is just another absent father, then belief in his providence is just another excuse for not taking responsibility for one’s life and engaging in self-parenting — or creating a Männerbund. (I wonder if Tyler’s burning chemical kiss was inspired by the “box” in Frank Herbert’s Dune. If so, the aim is very different.)

Now I want to discuss two questions. Is Fight Club fascist? And: Is Fight Club gay?

Yes, Fight Club is fascist. After all, Tyler Durden makes his soap out of human fat. That’s a joke, but with that detail, the author of the original novel, Chuck Palahniuk, is telling us something. Fight Club is clearly anti-liberal, anti-consumerist, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist. It is also populist, because it empowers ordinary men against the establishment. The only question is: Does Fight Club reject liberalism from the Left or from the Right?

The best way to answer that question is with another question: Does Fight Club admit women? No. Therefore, Fight Club rejects the essential premise of liberalism: human equality. Fight Club is populist, but it is not egalitarian. Fight Club is open to men of all social classes, not because it rejects hierarchy as such, but merely because it rejects the existing hierarchy and wants to create a new one, in which men who are willing to risk combat rule over those who don’t. But that’s also true of the Nazis and Fascists.

The Unabomber’s Manifesto spends a good deal of time critiquing Leftism from a loosely Nietzschean “vitalist” perspective, meaning the idea that a good society gives expression to the life force, thus any institutions that constrict it must be thrown aside. Leftists recoil in fear from such talk, because equality requires leveling and constricting, domesticating and socializing the life force. Leftism is over-socialization. Fight Club offers essentially the same critique, but it focuses specifically on masculine vitality. Leftism isn’t just over-socializing, it is also emasculating.

If Fight Club does not admit women, does that mean it is gay? The Catholic priesthood does not admit women. Does that mean it is gay? Uh-oh. There may be a point here. We can at least say that the movie plays with this question.

Fight Club is a bunch of men rolling around half-naked and punching each other. Some people find that. . . suggestive. Tyler declares: “We’re a generation of men raised by women. I’m wondering if another woman is really the answer we need.” Everyman seems to be sexually jealous when Tyler hooks up with Marla. He resents Marla for intruding on his relationship with Tyler. He also clearly feels jealousy of Tyler’s affection toward Angel Face, which sends him into a psychotic rage. [Note: Chuck Palahniuk revealed that he is gay in 2004.]

But in a deeper sense, the answer is obviously no. Tyler and Everyman are both heterosexual. Beyond that there is a matter of principle: It does not make men gay to want to work or socialize with one another while excluding women. Women have a great deal of power in pre-historic and post-historic societies because they are relatively egalitarian. Women have a great deal of power over children in all societies. Thus if boys are to mature into men, at a certain point they need to separate themselves from their mothers. They need male-only spheres for that. This is much easier, of course, when they have fathers. But when fathers are absent, they can find father substitutes. One such substitute is the Männerbund. Or, in less fancy terms, the gang.

Bonded male groups are not just necessary for the healthy maturation of boys. They are what create and sustain human history and culture. Almost every important institution until quite recently was sex-segregated. Institutions probably work best that way. Feminists, of course, want to break down those barriers, and one of their techniques is to insinuate that any institution that excludes them must be somehow “gay.”

Yes, progressive women are not above exploiting “homophobia” to get their way. If they were consistently progressive, they would be saying that men should not think being gay is a stigma at all. Men should not let themselves be manipulated like this. Maybe men should demand that they be allowed into all-female spaces, so that women can absolve themselves of the suspicion of lesbianism. Or better yet, both sexes could call a truce to this childishness. But men are the ones on the retreat, so things will only turn around if they assert themselves.

Fight Club has a cell structure. Fight Clubs can and do pop up everywhere. Fight Club meets once a week and exists only between certain hours. Then Tyler started handing out homework assignments. This is the speech he makes before the first assignment:

Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who have ever lived. I see all this potential. And I see it squandered. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas and waiting tables; or they’re slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man, with no purpose or place. We have no Great War, no Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war. Our Great Depression is our lives. We were raised by television to believe that we’d be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars — but we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed-off.

Tyler’s homework consists mostly of pranks and acts of vandalism. But they too are initiations, preparing the way for the next phase.

If the bonded male group is the origin of history, then we should expect Fight Club to go political. Thus Fight Club morphs into Project Mayhem. At that point, Tyler starts building bunkbeds, because Project Mayhem is a full-time commitment.

Project Mayhem is a cross between a goon squad and a Zen monastery. (But, then again, Zen is the religion of the samurai.) The members of Project Mayhem dress alike, submit to a charismatic leader, chant his cant like robots, and seem ecstatic at the prospect of immolating themselves for the cause. Freedom, equality, individualism, and creature comforts aren’t what they want. They want to be “space monkeys” who give their lives for the common good. As Nietzsche said, “Man does not strive for happiness; only the Englishman does that.”

The ultimate goal of Project Mayhem is to collapse industrial civilization and start history over again. Tyler envisions going back practically to the stone age:

In the world I see, you are stalking elk through the damp canyon forests around the ruins of Rockefeller Center. You’ll wear leather clothes that will last you the rest of your life. You’ll climb the wrist-thick kudzu vines that wrap the Sears Tower. And when you look down, you’ll see tiny figures pounding corn, laying stripes of venison on the empty carpool lane of some abandoned superhighway.

Phase one of collapsing civilization is blowing up the headquarters of the major credit card companies, erasing people’s debts. This is easy for Tyler, because if you know how to make soap, you know how to make dynamite.

We never learn what phase two is.

Indeed, near the end, Fight Club takes a psychological turn for the worse and becomes as anticlimactic as history itself. It is upsetting, because one really wants to like Tyler. But the modern media can’t convey profound anti-modernist messages without putting them in the mouths of madmen.

What is the lesson of Fight Club? The End of History in modern liberal-egalitarian consumer society is good at satisfying our desires for comfort, security, and long life. But we’re not satisfied with satisfaction. There’s more to the human soul than that. In modernity, masculine thumos is, for the most part, unemployed. In fact, it is regarded as a disturber of the peace. But idle hands do the devil’s work, and unemployed thumos, if mobilized by a charismatic leader and properly directed, can overthrow the modern world and start history over. Maybe next time, we will get it right.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [5] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.