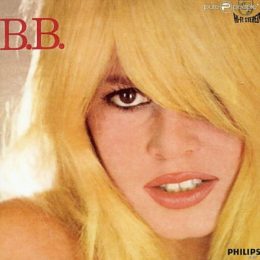

Brigitte Bardot’s B. B.

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 1,920 words

1,920 words

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot is a famed French actress, singer, pop culture icon, and accidental provocateur. Bardot’s marks on pop culture include her popularization of the bikini, the eponymous Bardot neckline, and her collection of absurdly fun and often intriguing slices of French pop music that feel both timeless in their replay value yet wholly products of a France long since lost; an era of unprecedented decadence and European pop-cultural renaissance. Bardot’s infectious voice exudes a sort of energy that one would be hard-pressed to ignore; her ability to toss various whoops and yelps into the cadence of otherwise butter-smooth diction gives her the ability to punctuate her tracks without the need for overbearing percussion. There is a certain “bounce” present in her tracks, a rhythm guided by her voice, that can put a smile on the face of even the dourest of monsieurs.

Bardot is also a controversial figure in France and the world more generally for her outspoken attitudes on animal rights. The curious thing about Bardot, however, is that her activism avoids just about every attribute of a fad; it seems to spring wholly from Bardot’s (admittedly liberal) worldview, the sort of thing that only a French lady would think to dream up. Her insistence upon Western norms in the treatment of animals has landed her in hot water multiple times, as she frequently speaks out against halal slaughter, Chinese treatment of animals, and eventually, the disturbing state of Modern France itself [1]. Bardot has been fined by the French government for “inciting racial hatred” a total of five times, and in every instance, these fines have been levied against her for a very basic kind of nationalism.

As the world’s attitudes, once favorable towards Bardot’s Franco-eccentrism, began to turn against her as part of the global shift towards tepid neoliberalism, Bardot stayed put in her convictions, and eventually began to realize that her enemies were no longer just slaughterers and abusers; it was the global regime of free trade and immigration, whose tolerance of France’s Muslim problem was anathema to her view of the world as an open society full of life. For simply stating her opposition to a foreign people’s values in her own country, Bardot was villainized [2]. Bardot is an outspoken French woman with a love for all things French; and knowing her bubbly attitudes, it would be slanderous to say that her views do not come from a place of innocence. Bardot came to endorse Marine le Pen in the 2017 French presidential election.

It’s things like this that give her music even greater appeal. A woman who once was a scandalous libertine has found herself in a world she no longer recognizes; rather than go with the flow, she held on to what she knew, which is an honorable thing no matter one’s previous convictions. Bardot is a kind of victim of her own design, as well, as the social machinations that initially propelled her to stardom — she was one of the world’s first sex symbols, after all — eventually led to the destruction of the society that made it all possible. It is easy to rail against the excesses of yesteryear, especially since we now know what their outcomes would be. But in the defense of those participating in them at the time, how could they have possibly known what would come next? Those ringing the alarm bells in Europe at the time were often met with violent ends, or became discredited, problematic figures in the national sphere. And besides, France had yet to meet the logical conclusion of its heydays, so lived experience in a multicultural hellscape was nil. This exoneration holds even more water when people like Bardot “repent,” for lack of a better word; Bardot certainly would not have voted for a National Front in the 1960s, but she’s doing it now. That’s a whole lot better than just about any of her peers who continue to toe the line, and a bold stance to take when gray heads are a regular sight among the “popular” Left and its rallies these days.

B. B., while not a proper “album” in the modern sense, is a compilation of Bardot’s work with producers and writers Claude Bolling, Alain Goraguer, Claude Dejacques, and Gérard Bourgeois. To choose just one moment from Bardot’s discography was a challenge, but B. B. felt appropriate as a representation; choosing B. B. also avoids most of Bardot’s unfortunate collaborations with notorious music industry Jew Serge Gainsbourg [3], as I want today to be a break from current events and a reflection on nice, white music.

B. B. opens with “Moi je joue,” a fine example of the bouncy energy previously discussed. “Joue” moves between its couplets with musical precision, but Bardot’s voice offers a more chaotic edge to the track’s sounds that leads to a complete whole. “Joue” is also a short song, clocking in at just 1 minute, 42 seconds; despite that, there is no sense of it being unfinished or ending prematurely. This is a common attribute of Bardot’s tracks — they tend to be as they are, and such Gestalt is difficult to replicate in music with the consistency that Bardot’s tracks do.

“Une histoire de plage” is slower and more somber, but not in a depressive way; “Plage” reminds one of coffeehouse soundtracks, or a piece of music used in a cinema score during transitions or establishing shots. In French, Bardot regales us with vignettes of the seaside, and of an ennui tempered by present contentment. Even without knowing the meaning of the words, “Plage” conveys a period of momentary rest during a period of personal tumult in its calm, but intentional instrumental.

“Ça pourrait changer” contains a break-like drum pattern and the introduction of more mainstream 60s pop elements like a thick bassline and call-response songwriting. Bardot’s “Yè yè yè yè!” is almost impossible to avoid shouting along to. “Changer” includes a heady mix of European musical tropes, such as its flourishes of Kinks-like synthesizer and chunky rhythm guitar. It is possibly the most “dated”-sounding of the album’s tracks, but in such a way that it is more akin to preserved amber than a fossil.

“À la fin de l’été” is another slow song, with some elements of a ballad melding with tasteful horn work and graceful guitar sweeps to create a perfect “chill-out” track. Music like this makes you want to drink wine on a balcony. Bardot’s versatility deserves mention here, as well, since she’s now drifted between two poles of energy over the course of the album so far without such a change disorienting the listener. One can mine Bardot’s discography for wildness and mildness and return with armfuls of both.

“Ne Me Laisse Pas L’Aimer” swings us back towards the more energetic Bardot, a dancefloor track with sprinklings of Latin music; Bardot’s range is also on display with “L’Aimer,” as she shifts between her high and middle registers for the couplets and refrains. The title literally means “do not let me love him.” If we take “him” to mean a fatal attraction, then perhaps Bardot’s wish came true after a long while.

“Maria Ninguen” is a sweet track, with jazzy influence and chop chords providing a solid foundation for Bardot’s intensely luscious interpretation of the bossa nova classic in its original Portuguese — her R’s roll like avalanches off the tip of her tongue, reminding us just how beautiful our spoken languages are in our own hands. Compare Bardot’s Portuguese serenading to the vocal gutterballs chucked about the streets of Rio de Janeiro.

“Je danse donc je suis” — I dance, therefore I am — is another dancefloor standard, and yet another example of Bardot and company’s remarkable ability to imbue their tracks with a certain timeless quality without abandoning the touchstones of the period; if one wasn’t already ware of Bardot and heard the track, it would not be a stretch to assume it was a modern take on popular swing tunes from Bardot’s period.

“Mélanie” slows things down again. The beauty of “Mélanie” lies in its gentle touches, such as its subdued woodwinds and meandering bassline, as they seem to walk around Bardot’s singing; despite its instrumental sparseness, “Mélanie” fills its space with grace.

“Ciel de lit” is a rather whimsical look at infidelity. Bardot tells a tale of a woman convinced of her faithfulness to two men at once — perhaps from personal experience? — and spins it into an unlikely episode of charming pseudo-innocence. The instrumental of the track is similarly bright. “Lit” is an example of romanticism that does not truly exist in this day and age; there is implicit silliness to its premise, and tongue-in-cheek rationalizations of the song’s described events. These days, a song about cheating would typically involve murderous rage, depressiveness, or a vindictive sort of feminist “liberation” that celebrates the harm of the act, typically towards men. The transgressiveness of such a thing is rather muted, whereas Bardot’s rather unique look at the situation invites scandal coated in bubblegum, and leads us to ask questions about what love truly is.

“Un jour comme un autre” is one track featuring Gainsbourg’s hand on B. B. It is somber — the title means “a day like any other” — and almost entirely forgettable.

“Les Cheveux Dans Le Vent” is another cut of exuberant, bubbly pop, similar to “Changer” and “Joue,” albeit this time with a double dose of percussion. “Vent” has the atmosphere of festival music, and like much of B. B., warrants playing at a reasonable volume on the patios of the world. “Vent” is unique for its constant structure, with its couplets coming one after another in the cadence as its refrain; the song seems to drive forward without stopping for one moment.

“Jamais Trois Sans Quatre” continues on the same high note; it is an upbeat, flute-graced track about summer love. Hearing such an enthusiastic ode to the warm season this year feels, in some ways, wrong; with the United States coming apart at its seams and Wu Flu rearing its ugly head when the news cycle is slow, there does not seem to be much to look forward to, nor any cause for relishing the present moment.

Perhaps, though, it is exactly this sort of pessimism that shall lead to no good. In an age of turmoil, where monuments to our past are being torn down, I argue that indulgence in our people’s oft-saccharine nature is not a form of escapism nor of ignorance, but a moral good, almost an obligation; to stew in destruction is to allow ourselves to forget what it means to be alive in the first place. To take a break every once in a while means to allow yourself time to recharge and to refocus; and to that end, I wholeheartedly recommend that this crazy blonde accompanies you in your moment of reprieve. If it’s Friday, the weather is warm, and a glimpse of the golden age saunters into your vision from a ray of sunlight, then put some Brigitte Bardot on. She’s a little quirky, a lot of fun, and for what it’s worth — on our side.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [5] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.